Criterion Blu-ray review: The Honeymoon Killers (1969)

At the end of the 1960s, with the complete collapse of the old studio system and the end of the Production Code which had maintained “moral standards” in the movies produced by Hollywood for more than three decades, there were radical changes in the ways in which movies were made and with what could be shown on screen. In a reaction to decades of repression, sex and violence bloomed with a vengeance. Things which had previously been staples for less reputable companies – the American-Internationals, the Lipperts and so on, purveyors of youth-oriented exploitation in the ’50s – found their way into productions released by the surviving majors. This was the era of The Wild Bunch (1969) and Bonnie and Clyde (1967), movies which shattered existing limits on what kind of behaviour could be depicted on screen.

This new freedom also encouraged independent production, with people not previously connected to the business throwing in small pools of money to make movies outside the mainstream. In 1969, television producer Warren Steibel suggested to his friend Leonard Kastle that they make a movie. Kastle, a composer and opera librettist, was game. Steibel got $150,000 from another friend and suggested that they tackle the story of the Lonely Hearts Killers, Ray Fernandez and Martha Beck, who killed as many as twenty women in the late forties and were executed for their crimes in 1951. With neither Steibel nor Kastle having previous filmmaking experience, they just winged it. Steibel suggested that Kastle write the script, which he did with the aim of making an “anti-Bonnie and Clyde”, having despised what he saw as that film’s glamorization of its criminal pair.

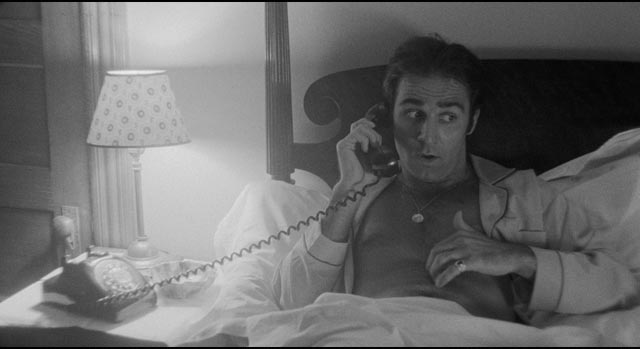

In Kastle’s script, based quite closely on records of the actual case, the killer couple are anything but glamorized. Fernandez is a sleazy con-man preying on vulnerable, generally older women, while Martha is an overweight nurse with self-esteem issues. When Martha (Shirley Stoler), at the urging of a friend, reluctantly signs up with a “lonely hearts” agency, she receives a charming letter from Ray (Tony Lo Bianco). He comes to visit and she becomes infatuated; but she has nothing to offer in the way of profit so he heads back to New York. Martha uses a fake suicide attempt to regain his attention and follows him to New York, establishing a relationship which is perverse yet mutually supportive.

Posing as Ray’s sister, Martha accompanies him on his wide-ranging travels to hook up with women he’s met through the match-making service. While her presence seems to serve as a reassurance to his victims, his interactions with these women provoke jealousy and resentment in Martha. This in turn begins to interfere with the normal course of his “business”. In Kastle’s telling, it is Martha who introduces murder into the mix, by giving poison to Myrtle Young (Marilyn Chris). This was the first of three murders with which the couple were eventually charged.

The second, the movie’s centrepiece, was the killing of Janet Fay (Mary Jane Higby), a 66-year-old widow who moved into the couple’s Long Island apartment in preparation for marrying the younger man. The staging of this murder foreshadows later films like Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986) in its mix of brutality and black humour. Here, it becomes apparent that the couple’s crimes have become the deepest expression of their emotional bonds – as Ray says to Martha, “You’ll do it if you love me.” At which point she beats Janet over the head with a hammer, then hands Ray a scarf with which to strangle the stunned woman. After this, it seems that nothing is beyond them, leading to the film’s most shocking moment involving the young daughter of their final victim.

When The Honeymoon Killers went into production in 1969, Kastle and Steibel having already cast it, Martin Scorsese was hired to direct. At the time, he had only a few shorts and one feature (Who’s That Knocking at My Door? [1967]) to his name; in the first week he did shoot a couple of scenes (in particular, the lakeshore scene in which Martha almost drowns herself in a jealous rage when Ray pays too much attention to their intended victim), but Kastle and Steibel quickly became concerned about the amount of time he was taking given the very limited budget and tight shooting schedule. And so Scorsese was fired and, after looking at other options, Kastle took over despite never having directed before. Here, the support of cinematographer Oliver Wood was crucial.

Shot in black-and-white, with a largely hand-held camera which owed a lot to the vibrant ’60s documentary movement, not to mention the truly independent films of John Cassavetes, The Honeymoon Killers has a stark, naturalistic look, making use almost entirely of available light (including a strikingly effective use of practical lamps in interiors). This visual approach was a deliberate rebuke of the lushly romantic look of Bonnie and Clyde, an effect reinforced by the film’s emphasis on the grotesque, although as it progresses, taking Ray and Martha’s point of view, it gradually “normalizes” the couple and even develops a degree of empathy for them despite their sociopathology.

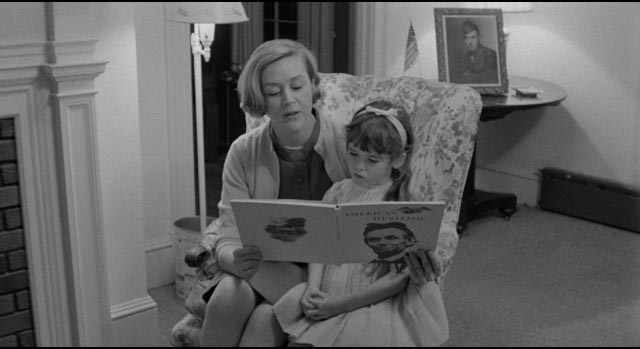

The danger in this kind of movie always lies in how victims are treated and The Honeymoon Killers treads a fine line. There is a satirical element in its approach, most pronounced in its depiction of the exaggerated patriotism of two of these women, as if they stand for a naive post-war image of the country rooted in storybook simplicities which are confronted by the brutal practicality of capitalist self-interest exemplified by Ray’s “business”. (Here, the film owes an obvious debt to Chaplin’s masterpiece Monsieur Verdoux [1947].) And yet Kastle also allows these women sufficient space to exist as characters who themselves have dreams and desires, albeit of an “old-fashioned” kind rooted in the traditional values of marriage and family as an essential purpose for women. In fact, to a degree some of these victims themselves use duplicity in trying to land Ray as a desirable catch – a “sexy” younger man who reinvigorates them.

Perhaps the film’s deepest irony lies in the fact that Ray himself is trapped by Martha through deceit – he’s suddenly convinced that she’s desirable because the faked suicide attempt, her apparent willingness to kill herself for love of him, confirms for him his own romantic value. Although a long-time predator and exploiter of vulnerable women, he finds here a strange sense of self-worth in her feigned vulnerability; in a classic case of folie à deux, they feed on and amplify each other’s essential weaknesses, and their acts of murder intensify and reinforce their unhealthy emotional bond. This bond is only broken in the end when Martha discovers that Ray has betrayed her and, in her turn, she betrays him – because the only way to guarantee their exclusive relationship is by being bound together publicly by their crimes and inevitable terminal punishment.

Despite being Leonard Kastle’s first (and ultimately only) film, The Honeymoon Killers is a remarkably well-controlled piece of work, full of darkly comic and horrific moments and graced with superb performances which tread skillfully between those poles of horror and comedy. It comprehends, but does not valorize, the sources of the couple’s crimes. Interestingly, given his early involvement, it foreshadows the kind of fluid, often elaborate long takes which characterize Scorsese’s work. (Recalling Pauline Kael’s negative review of The Honeymoon Killers in the New Yorker, I looked it up after watching the film again, and was surprised and amused by her absolute certainty that this is a “very badly made film”.) Kastle considered himself an amateur, and as sometimes happens, that amateur status allowed him to approach the project without the kind of baggage a trained filmmaker might bring to it; he did what he wanted to do rather than what might be considered the “right thing” and the results are fresh and in some ways ahead of their time. His freer, more naturalistic approach would soon become the new rule.

Perhaps even more impressive than the look of the film is Kastle’s work with the actors. Both Tony Lo Bianco and Shirley Stoler were new to film at the time (in effect, this film launched both their careers) and their performances are remarkable. While the stresses of their “work” create tension and bickering, the film does eventually become a genuine love story; unable to conceive of empathy for their victims, this pair develop a deep emotional bond which lasts up to the moment of their executions. Balanced against this is a gallery of fine supporting performances: Mary Jane Higby as Janet Fay; Marilyn Chris as their first victim, Myrtle Young; Kip McArdle as final victim Delphine Downing; Doris Roberts as Martha’s friend Bunny who initiates it all by urging the nurse to apply to the lonely hearts agency; and Dortha Duckworth in the small but significant role of Martha’s mother.

Kastle succeeded in his aim of countering the mythologizing of Bonnie and Clyde by creating a rich collection of sad and pathetic yet terribly plausible characters whose encounters while seeking some kind of affirmation of their own personal worth result in tragedy.

The disk

Criterion’s new 4K transfer and restoration is a definite improvement in both picture and sound over their 2003 DVD edition. The hi-def image has strong contrast and captures the original black-and-white negative’s pronounced grain for an authentic film look. The mono soundtrack provides clear dialogue and strong presence in the score which consists entirely of selections from Mahler’s symphonies, giving the film additional dramatic depth.

The supplements

The Blu-ray carries over the original DVD’s interview with Leonard Kastle (29:38), who comes across as very engaging in his account of the film’s production. It was not, it turns out, his own choice that it remained his only film; before his death in 2011, he had tried to launch a number of projects over the intervening four decades, all without success despite the reputation of his debut feature. He also has some amusing stories about initial dealings with distributors.

There are two substantial new supplements: Robert Fischer’s Love Letters (24:59), featuring interviews with actors Tony Lo Bianco and Marilyn Chris (who introduced Kastle to Shirley Stoler) and editor Stan Warnow. They discuss the casting process and shoot in some detail – with some conflicting comments about what actually happened with Martin Scorsese.

And finally a visual essay, “Dear Martha …” (22:56), by Scott Christianson, author of Condemned: Inside the Sing Sing Death House, which is expanded from a text supplement on the DVD; this sketches in details of the real Lonely Hearts case, pointing out the film’s accuracies as well as other details which were elided or altered by Kastle. Most of these changes were apparently made to streamline the narrative (Martha, for instance, actually had two children, whom she dumped at the Salvation Army in order to pursue her relationship with Ray).

The booklet essay by Gary Giddins is a revised version of the one he originally provided for the DVD release.

Comments