Italian genre beyond Bava

Dario Argento

My first encounter with the giallo was, paradoxically, in the small prairie town of Neepawa, Manitoba, population 4000, in 1973. At the Roxy Theatre, where shows changed three times a week, if I liked a movie I would often go again to see it a second time on the following night. This happened with Dario Argento’s Four Flies on Grey Velvet (1971). By that time, I had probably read reviews of his first two features in Cinefantastique, so I may have had a vague idea of who he was. But certainly I had never before seen anything quite like Four Flies, which was the third part of his “animal trilogy”, three films which virtually defined the genre and inspired countless imitations.

I don’t think I caught up with his first two features – The Bird With the Crystal Plumage (1970) and Cat O’ Nine Tails (1971) – until years later, after I’d become a confirmed fan with the release of Suspiria (1977). By then, I knew that Four Flies was certainly not his best work, but it has nonetheless retained an attraction for me simply because it was the first one I saw. It has also, until the past few years, remained the rarest of his thrillers. After that first encounter in 1973, it was more than thirty years before I had another opportunity, when I tracked down a German DVD edition (with mediocre picture quality). It was about five years ago that the film got a North American release on disk (also not very impressive technically). But I recently picked up a Blu-ray edition released in 2012 by Britain’s Shameless, which looks probably as good as it did back in the day on the Roxy’s screen. This disk restores some previously cut bits and pieces and offers both English and Italian audio, along with an interview featurette with Luigi Cozzi, co-writer and assistant director on the film.

Argento, perhaps more than any other filmmaker, built on the foundation established by Mario Bava in his pair of thrillers from 1963 and ’64, taking the narrative structure of The Girl Who Knew Too Much and the stylistic excess of Blood and Black Lace to create films steeped in psychological derangement. Argento has worked within the genre more consistently than any other filmmaker, although most Italian commercial directors have turned out one or more gialli at some point in their careers, some of them quite masterful – Lucio Fulci in A Woman in a Lizard’s Skin (1971), Don’t Torture a Duckling (1972) and The Psychic (1977); Sergio Martino with The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh (1971), Your Vice Is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key (1972) and Torso (1973); and among others Aldo Lado, Pupi Avati, Massimo Dallamano – but by and large, the genre was already descending into self-parody by the late ’70s. In fact, Argento’s later attempts to keep the form alive themselves gradually became embarrassing parodies – from the dull shot-in-the-U.S. Trauma (1993), to the ambitious but largely unsuccessful The Stendahl Syndrome (1996), and the increasingly pointless Sleepless (2001), The Card Player (2004), and finally the dire, hubristically-titled Giallo (2009).

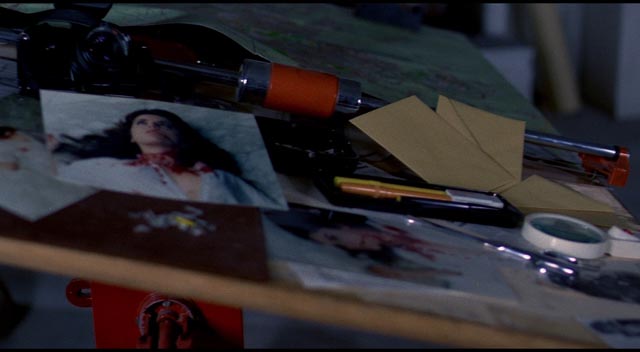

But at his height, his work was often masterful. At heart there was always a pulpy absurdity to the narratives and their reliance on often implausible plot devices – the homicidal XYY chromosome of Cat o’ Nine Tails, the imprinting of a final image on a murder victim’s retina in Four Flies. But as in Bava’s work, the essence of Argento’s best films has always been the creative fusion of that central psychological derangement with a visual style which embodies the madness of homicidal characters. The familiar killer’s-eye point-of-view, with the camera stalking potential victims, which became the most notable element of American slasher films from the late ’70s and ’80s, was born in the giallo. But beyond this, there is the crucial theme of faulty perception, the idea that we can never be quite sure of what we have just seen. A corollary of this is an almost obsessive focus on close-ups of eyes, whether of a protagonist striving to see something which is partially obscured or of a voyeuristic stalker spying on an unsuspecting victim. This element gave rise to one of the most distinctively disturbing tropes of Italian horror, best exemplified in a string of horror films by Lucio Fulci, which might be termed “eye trauma”. The vulnerability of the eye and the fear of losing one’s sight, with the concomitant loss of ability to protect oneself, makes for some of the squirmiest moments in cinema.

In addition to the Four Flies Blu-ray from Shameless, I’ve revisited several other Argento features on Blu-ray this year, including Cat o’ Nine Tails (1971), the horror-giallo hybrid Phenomena (1985), and Inferno (1980), the supernatural horror companion to Suspiria, all from Arrow Video. Most recently, I’ve re-watched what some critics and fans consider the director’s giallo masterpiece, Tenebrae (1982), although Deep Red (1975) and Opera (1987) also have their advocates. In Tenebrae, Argento backed away from the visual excesses of Deep Red, Suspiria and Inferno (the latter, incidentally, being the final film on which Mario Bava worked, as a visual consultant and designer of effects); to some degree a return to the style of Bird With the Crystal Plumage, Tenebrae is visually a very cool film with an emphasis on almost inhuman architectural spaces (although shot on actual locations if has an oddly detached futuristic ambiance). Perhaps the most famous element of the film is an incredibly elaborate crane shot which seems to imbue the familiar point-of-view stalking-camera with an unexpectedly supernatural inflection (although, unlike Suspiria and Inferno, Tenebrae is definitely not a supernatural film); the camera prowls outside a house, spying through windows at the two women going about their business inside, then rises up the wall and skims across the roof and down again to a second-storey window, so what at first seems like the killer’s point of view turns out to be something more numinous, the disinterested perspective of some godlike presence observing the moments leading up to a brutal murder.

The second distinctive element in the film is the discovery that there are actually two murderers, an echo of Blood and Black Lace, although here the killers are not working in concert; one is influenced by the published work of the other, while the second is inspired by the first to act out suppressed desires rooted in a humiliating adolescent experience. Argento skillfully manipulates this misdirection to add narrative layers which give Tenebrae greater complexity than his other gialli.

Arrow’s dual-format release features a new hi-def transfer, English and Italian audio options; two commentary tracks (one with English critics/fans Kim Newman and Alan Jones, the other a rather dry and academic effort from Thomas Rostock); an introduction by Daria Nicolodi, who also gets an interview featurette; an interview with Argento himself; a featurette with Maitland McDonagh, who wrote the first serious book about the director, Broken Mirrors/Broken Minds; an interview with Claudio Simonetti about Goblin’s score, as well as a live performance by the band of tracks from both Tenebrae and Phenomena. The booklet features an essay by Alan Jones, an interview with cinematographer Luciano Tovoli, and an appreciation by Berberian Sound Studio-director Peter Strickland.

*

Lucio Fulci

Lucio Fulci, like so many Italian directors, worked in multiple genres during a career that spanned more than thirty years, but it was as a horror filmmaker that he attained international success – ironic since he had no particular liking for horror. Prior to his big hit Zombie (1979), he had made comedies, adventure films, sex comedies, westerns, action thrillers and gialli, as well as the historical drama Beatrice Cenci (1969), which some consider his masterpiece, though now it’s virtually impossible to see (I haven’t seen it myself, though I’d like to). His gialli from the ’70s are some of the most interesting films in the genre, but after the success of Zombie he got trapped in horror and, again ironically, he found the budgets available to him growing progressively smaller through the ’80s, and his work became shoddier and coarser until finally his movies were virtually unwatchable.

My first encounter with his work, in Hong Kong in 1981, was a screening of City of the Living Dead (1980). Looking at my notes from back then, I see that I had a very low opinion of it. My attitude to Fulci didn’t improve when I finally saw Zombie back in Winnipeg in 1982. My opinion has changed over the years, however. I might point out that my notes indicate that I also didn’t like the movies of David Cronenberg when I first saw them in the late ’70s and early ’80s, an opinion which changed significantly when I saw Videodrome in 1983; I grew to admire all his previous films as I re-encountered them in subsequent years. I wouldn’t put Fulci in the same class as Cronenberg, but I now find his work much more interesting than I once did.

In his horror films, Fulci pushed the boundaries of gore and his shocking set-pieces seemed to be the only reason for the movies’ existence. Their lack of narrative and often outright incoherence reinforced that impression. Strangely, it’s their incoherence which now makes them more interesting. His best work has the power of dream logic, a nightmarish tone which adds a deep sense of unease out of which the eruptions of violence flow. The absence of a realistic narrative foundation makes the horror inescapable, something which reaches its apotheosis at the end of his masterpiece, The Beyond (1981), which leaves its two protagonists trapped in a genuinely chilling vision of Hell.

Zombie (1979, aka Zombie 2 aka Zombie Flesh Eaters) came about through the classic exploitation process by which cheap knock-offs are rushed out to cash in on a recent success, in this case George Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978). However, despite being marketed as some kind of sequel, Fulci’s movie actually harks back to the classic zombie of voodoo, grafting Romero-esque gore onto an island setting which echoes White Zombie (1932) and I Walked With a Zombie (1943). The movie opens with an effectively chilling sequence with an apparently abandoned yacht sailing into New York harbour; when police board the boat, a crazed, decaying zombie attacks them. Reporter Peter West (Ian McCulloch) teams up with Anne Bowles (Tisa Farrow), whose vanished father was connected with the boat, and they head for a remote Caribbean island called Matoul where they find themselves in a nightmare, the dead rising to eat the living for no discernible reason. (One of the movie’s most endearing absurdities occurs on the way to the island, when we get to see a titanic underwater fight between a zombie and a shark.) On the island, we meet Dr. Menard (Richard Johnson, giving the film some genuine gravitas), who is trying to isolate the pathogen responsible, seeking a cure, while dealing with an alcoholic wife and a disintegrating marriage.

Zombie displays three of the key characteristics of Fulci’s work: an often impressive ability to create striking images, like the shot of a dusty, deserted windblown street with a crab scuttling across the foreground while a shambling zombie approaches from the distance; the disturbingly intense staging of moments of graphic violence, including here the legendary “eye trauma” moment which precedes the death of Dr. Menard’s wife which, although it obviously involves the use of prosthetic make-up, is staged and edited for maximum audience discomfort; and finally, the thing which is most likely to irritate a viewer and create a negative opinion of the director’s work, his strange penchant for having characters stand immobile while some very slow-moving threat approaches. This last can be seen as an odd failure to stage action effectively or alternatively as an element of an overall dreamlike approach to the material – as in a dream, these characters are trapped in the scene, unable to escape. I think it was this aspect which initially gave me a low opinion of Fulci’s work, and in truth it still irritates me – why don’t these people simply hurry away from a threat which could never catch them if only they would move! – although my overall opinion of these films has risen over the years.

Arrow’s two-disk Blu-ray presents the film in a perhaps slightly too bright transfer (DVD Beaver’s comparison shows the Blue Underground transfer with richer colours), but in every other respect it’s impressive. The image looks pristine and the original mono sound tracks (both English dub and Italian) are clear, with a strong sense of atmosphere. The edition is packed with too many extras to mention in detail, including a pair of commentaries – one with credited writer Elisa Briganti, who as on many other films collaborated with her prolific husband Dardano Sacchetti; the other with critics Stephen Thrower and Alan Jones, both of whom had personal experiences with the apparently very difficult Fulci. While recognizing the movie’s various shortcomings, all three commenters express a great deal of affection for it, and for Fulci’s work in general. In addition, there are numerous featurettes and documentaries dealing with the production, the zombie film in general, the make-up and effects, and the music. Star Ian McCulloch has a lengthy interview in which he talks about the film and his career and, like Catriona MacColl on other Fulci releases, talks about being initially embarrassed by his part in Italian horror, thinking at the time that no one would ever see the films, but subsequently coming to accept their popular status and taking some pride in his own role in these productions.

City of the Living Dead (1980) might not have been the best starting place for a relationship with Fulci’s work. The story is largely incoherent and several of the deaths are grotesque in the extreme. With a nod to Lovecraft, the setting is the town of Dunwich in New England, where a priest has recently committed suicide, apparently opening one of the Gates of Hell (an alternate title of the movie). A psychic named Mary (Catriona MacColl in the first of her three films with the director) has visions of some kind of coming apocalypse and, teaming up with Peter Bell (Christopher George), a glib New York reporter, heads to the town. Little of what goes on makes much sense, with visions of the dead priest triggering gruesome deaths and corpses returning to life looking to do what zombies tend to do. Many of the film’s set-pieces are effective and the overall air of derangement gives it a dreamlike atmosphere even more pronounced than that of Zombie. The tone is bleak to the point of nihilism, with a final image which is left so open that it might be read as tentatively positive or utterly hopeless … for those to whom the film appeals, the latter is more likely.

The sense of wildly unpredictable events which, thirty-plus years ago, seemed to be a problem for me has become over time – particularly in the wake of leadenly literal horrors like the Saw and Hostel franchises – the film’s chief attraction. Although stylistically and culturally very different, these Italian horrors share something of the irrational appeal of J-horror, the deep sense that the world isn’t nearly as solid and comprehensible as we like to think.

The Arrow Blu-ray (from 2010) is, like many of their older releases, weaker than what we expect from the company today, although the visual quality is an improvement over previous DVDs. (According to DVD Beaver, it was originally shot on 16mm, which would explain the pronounced graininess of the image.) The extras include two commentaries; one with Catriona MacColl, who has fully embraced her position as an iconic star of gory Italian horrors; the other with actor Giovanni Lombardo Radice, whose character meets one of the film’s most gruesome ends. There are featurettes with actors MacColl, Radice and Carlo De Mejo; scriptwriter Dardano Sacchetti; Fulci’s daughter Antonella and director Luigi Cozzi remembering Fulci; a piece on Fulci which focuses more on House By the Cemetery than City of the Living Dead; and a Q&A with MacColl and Radice recorded after a screening in Glasgow.

The Beyond (1981) is Fulci’s horror masterpiece, a film steeped in an atmosphere of apocalyptic dread all its own. While it borrows the “gates of Hell” idea from City of the Living Dead, it develops the idea with greater thematic richness. Set in Louisiana in an old hotel being revived by Liza Merrill (Catriona MacColl), who has inherited the rundown building, it presents a world where material reality is a thin veneer over a Lovecraftian abyss, which was opened up in the film’s ’30s-set prologue by an artist whose unholy painting depicting visions of Hell have caused angry locals to turn up in the middle of the night to inflict a brutal death in hopes of closing the rift. When Liza begins to restore the hotel, she inadvertently reopens the gateway, causing time and space to decay. She encounters the blind psychic Emily (Cinzia Monreale), who may be a ghost who has managed temporarily to escape the underworld to offer a warning. Aided by local doctor John McCabe (David Warbeck), Liza tries to unravel the mystery, only to find herself sinking deeper into the horror, triggering violent deaths and causing the dead to rise up for the nightmarish finale which finds Liza and McCabe attempting to flee the zombies and ending up trapped in Hell.

Although there are moments when certain effects undermine the movie’s power – particularly in an attack by spiders which mixes some real tarantulas with obviously mechanical bugs – Fulci here creates some of his finest imagery and his most successfully sustained atmosphere of oneiric dread.

The Arrow Blu-ray once again contains two commentaries, a discursive one with Fulci’s daughter Antonella which offers insight into her father’s work and personality, and an engagingly chatty one with MacColl and the late Warbeck, which is like hanging out with a couple of friends reminiscing about a fun time in their lives. There’s an on-camera interview with actress Cinzia Monreale and a Q&A with MacColl following a screening in Glasgow. A second disk (on DVD) has a featurette with MacColl, which covers some of the same ground as the commentary and Q&A; another with Gianetto Di Rossi about his effects work; and another with Italian directors speaking about Fulci and his work. Perhaps most entertaining of all is an interview with Louis Fuller, the exploitation distributor who brought the film, among others, to the U.S. He has a lot to say about the process of grindhouse releasing, including re-editing films and creating often highly misleading advertising campaigns to attract an audience.

*

Footnote:

Although the golden age of Italian horror and the giallo lasted barely twenty-five years, from the beginning of the ’60s to the mid-’80s, these films have paradoxically grown in stature with the intervening decades. Dismissed by most critics at the time, many of them have since gained respect for their cinematic qualities and even the most wretched have found lasting popularity on video. While these filmmakers may not have seen themselves as artists, the best of them were dedicated craftspeople (the level of quality in these Italian films is generally much higher than that of American exploitation movies from the same period), and the stylish movies they made have become a source of inspiration for later directors like the Belgian pair Hélène Cattet and Bruno Forzani and Peter Strickland in England. The Strange Color of Your Body’s Tears (2013) by the former and Berberian Sound Studio (2013) by the latter use techniques derived from the giallo to explore the ways in which style can create experiences of deeply unsettling paranoia; both are meta-texts whose subject is the cinematic apparatus itself and how we engage with it psychologically and emotionally.

Even Winnipeg’s own Astron-6 collective, a group of local filmmakers given to parody and pastiche, have followed up their slasher-horror Father’s Day (2011) with a movie rooted in the deranged world of the giallo. Written and directed by, and co-starring, Adam Brooks and Matthew Kennedy, The Editor (2014) sticks pretty much to surfaces, however. They use tropes from the giallo – the black-gloved killer, the hero who seems unbalanced and attracts the attention of the police for possible involvement in the murders, and the more-or-less arbitrary string of events which go to make up a plot which never really makes sense – but they never find the more disturbing core because, as in their other work, their interest is in mocking rather than exploring their sources. The Editor remains superficial, trying to hold audience attention with its hit-or-miss gags rather than with a narrative and characters who engage the audience on their own terms.

Comments