Kinji Fukasaku’s Yakuza epic

I first became aware of Kinji Fukasaku about fifteen years ago, when I heard about Battle Royale and bought a region 3 Hong Kong-made DVD on eBay. Since then, I’ve re-bought the film a number of times (a special edition DVD from England, and more recently both the Arrow region B and Anchor Bay region A Blu-ray sets). It still seems remarkable that this devastating, violent satire was made by a director who was 70. The anger-fuelled violence of Battle Royale is something which runs through almost all of Fukasaku’s work, and was firmly rooted in his experiences growing up in Japan during the Second World War; he was born around the time Japan invaded China in the early ’30s and, as a junior high school student, was made to work in a munitions factory towards the end of the war, where he saw many of his friends die horrible deaths from U.S. air raids. The disconnect between Imperial propaganda, which constantly declared imminent victory, and the catastrophic events he himself witnessed gave Fukasaku a deep distrust of authority.

Fukasaku, inspired by the flood of foreign films into Japan under the U.S. occupation in the years immediately after the war, pursued a career in the movie business and, like every Japanese director of the time, he entered one of the studios as a trainee/apprentice and gradually worked his way up to director by 1960. That studio was Toei, something of an upstart noted for churning out an endless stream of genre movies to fill its own theatres with disposable double-features.

Toei, despite its lack of prestige, turned out to be very influential on the post-war direction of Japanese cinema. Although costume films rooted in Japan’s feudal past were banned during the occupation because they inevitably conjured up the forces which underlay Japanese militarism, swordplay films became very popular again through the mid and later ’50s, both in Japan and internationally. Yet the genre began to wane in the early ’60s as the economic boom transformed Japanese life. Toei was at the forefront of the emergence of a new genre which grew out of the traditional swordplay movies: the gangster film centred on yakuza, a criminal class which in some ways represented a modern equivalent and distortion of the samurai.

The core of the samurai film was the idea of loyalty and sacrifice, the central ideas controlling Japanese society throughout the militarism of the first half of the 20th Century. Those ideals were transposed in the modern urban setting of yakuza movies to violent men who swore allegiance to criminal “families”. In the initial years of the genre, the lives of these men were romanticized like the lives of samurai, although their situation was somewhat different; their lives were no longer shaped by the rigid rules of the larger society, but rather went against the grain of modern life. Rather than upholders of a rigid order, these men were outlaws, a state which created the moral conflicts which the genre largely dealt with. The yakuza hero ultimately had to make a principled stand against people worse than himself, frequently sacrificing his own life to defeat evil.

As younger directors rose through the ranks, these attitudes began to mutate and Fukasaku was one of the key players who eventually blew the genre apart – beginning with films like Japan Organized Crime Boss (1969) and Street Mobster (1972), his 21st and 26th features. But until 1973, despite being prolific, Fukasaku wasn’t particularly successful commercially as he worked in numerous genres (including what may have been his best known film in the west for a long time: The Green Slime [1968], pulp sci-fi shot in English). That all changed in 1973 with the first of five films which not only brought him respect (and some condemnation), but also changed the way yakuza were perceived in popular culture.

Battles Without Honour and Humanity is really one long film in five parts, released rapidly in 1973 and 1974 (the first was quickly followed by Hiroshima Death Match, Proxy War, Police Tactics and Final Episode), an eight-hour epic depicting not simply the progress of various criminal factions in Hiroshima from 1946 to around 1970, but also creating a savage metaphor for the dark side of the post-war recovery which made Japan one of the world’s most powerful economies. These films, made around the time Coppola was creating his elegant, elegiac portrait of American capitalism in the Godfather films, owe more stylistically to the French New Wave and similar movements of the ’60s than to classical Hollywood. Fukasaku and scriptwriter Kazuo Kasahara use a kind of narrative shorthand to tell a complex story involving dozens of characters spread across decades; packed with detail and incident, the pace is so fast and compressed that it risks losing the audience in a blur of confusion.

The first film begins explosively (literally) with an image of the atomic cloud over Hiroshima, implying that the emergence of the violent gangs involved in the black market was something like the unleashing of Godzilla, a horrific destructive force turned loose in the broken nation. From this image, we are immediately plunged into the midst of disorienting, violent action as several American soldiers chase a Japanese woman through a busy market and begin to rape her in full view of the cowed population. When a man we come to know as Shozo Hirono (Bunta Sugawara) drags the soldiers off her, the police try to restrain him, to prevent him provoking the Americans. Although the traumatized woman escapes, everyone in the area scatters as MPs approach – the implication is that the actions of the Japanese man in protecting the woman constitute the crime which has just been committed, not the rape itself. This chaotic and disorienting opening sequence is a potent visual metaphor for the humiliation of defeat which fuels the anger of the young men who join the gangs and drives them to express themselves through violence.

Shot handheld, with rapid, jarring editing, the scene establishes an overwhelming sense of instability, a tone which is remarkably sustained throughout all five films. This is an epic evocation of chaos and the series depicts the cost of what it takes to survive in such a state. If there’s a focal character in this teeming work, it is Shozo Hirono, a former soldier who initially drifts into the criminal life because there are no other options. His story – of allegiances, betrayals, complicated loyalties and a growing sense of disillusion and ultimately disgust – is woven through a complex narrative of multiple families, and the increasing intersection of criminality, business and politics, which implicates every level of society.

To be honest, watching the films again on Arrow’s new Blu-ray set, I was just as confused as when I watched them ten years ago on the long out-of-print Homevision DVD set. There are so many characters and the films’ pace is so rapid – shady claustrophobic interior scenes of men scheming quickly alternating with bursts of brutal violence – that it’s really hard to keep track of who is doing what to whom and why. But this is itself a deliberate strategy; the characters themselves are as often confused about what’s going on as the audience, acting out of that confusion and as often as not causing escalating complications which generate more violence, more confusion. The foot soldiers, as in the war, are disposable while the gang leaders scheme to consolidate their own power, using and discarding the men whose loyalty they demand.

The structure of these gangs reflects Japan’s feudal history while exposing that history’s illusion of nobility and sacrifice as a mechanism imposed from the top down purely for the benefit of the bosses. After Battles Without Honour and Humanity, it was impossible to sustain the romantic view of the yakuza and the many movies which followed, from Toei and other studios, followed Fukasaku and Kasahara’s lead with an endless stream of nihilistic violence delivered in a raw documentary-like style. (The series was based on actual events and the real people involved in them. One of the films’ most radical innovations isn’t apparent to a non-Japanese audience: for the first time in Japanese cinema the characters spoke in the distinctive vernacular of Hiroshima rather than the standard language – a development similar to the sudden explosion of Northern and working class accents in British film during the previous decade.)

Although Fukasaku remained little known outside Japan in the next three decades, until the arrival of Battle Royale, his influence can be seen clearly in the work of the next generation of Japanese filmmakers – people like Takashi Miike, Sono Sion, Kiyoshi Kurosawa. These films, more than forty years old now, still have the power to shock and disturb. But the genre itself was burning out by the late ’70s and Fukasaku went on to other things, directing a mixture of costume epics[1], fantasies and melodramas, most of which had little impact outside Japan. The range of his work gives his career a somewhat unfocused appearance, reminiscent of a journeyman studio director, and yet his best work bears the clear imprint of a committed auteur.

Perhaps the remarkable individuality of Fukasaku’s work is best exemplified by his final two features, a pair of films so radically different from one another that they seem like the work of two different directors: The Geisha House (1998) is a sensitive drama scripted by the prolific writer and director Kaneto Shindo, reminiscent of Mizoguchi and Naruse, which depicts the effects of a major social change on a young girl who is preparing to apprentice as a geisha just as anti-prostitution laws put an end to those traditions. This was followed just two years later by the violent explosion of Battle Royale. And yet that film too depicts the effects of a harsh society on its children. And both hearken back to Fukasaku’s own experiences as a child at the end of Japan’s imperial age, a time which used rigid social rules and violence to crush individuals and demand blind, and often fatal, obedience to the ruling class.

*

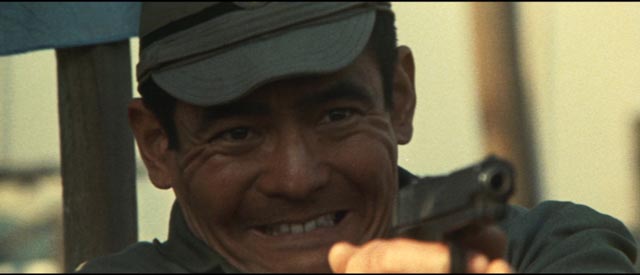

Arrow’s 13-disk Battles Without Honour and Humanity dual-format set reflects the origins of these films in fast, low-budget production; shot largely handheld and often in available light, the imagery is harsh and grainy, imparting a strong documentary-like feel. The performances have a heightened, aggressive tone familiar from the genre, with intense angry men facing off in claustrophobic meetings and erupting frequently into convincingly realistic moments of violence, which are as clumsy and messy as they are frequently futile.

The disks contain a number of supplements – interviews with people who worked on the films, both behind and in front of the camera; Fukasaku’s son Kenta; Koji Takada, who scripted the fifth episode; a commentary on the first episode by Stuart Galbraith IV, who covers much of Fukasaku’s career and the genre, as well as specific information about the production and influence of Battles. There is also an additional disk with a cut-down omnibus version of the first four films made for theatrical release in 1980. Not surprisingly, despite compression and a certain amount of simplification, this remains dense and confusing and, watched immediately after the five films, the absence of a number of key sequences is really noticeable. This 224-minute version, called “The Complete Saga”, comes with a brief but interesting introduction by Toru Dobashi, who supervised the new edit at Fukasaku’s request, in which he points out one of the main difficulties of the job: multiple actors were used throughout the series, portraying different characters.

The limited edition box set (2500 copies each in region A and B) also comes with a 150-page hardcover book containing numerous essays about the series, the genre and Fukasaku – including a long interview with the director conducted by Mark Schilling in 2002, the year before Fukasaku’s death; Paul Schrader’s Film Comment essay about the genre from 1974, which is a combination of scholarly study and self-promotion as he was then working on the script of Sidney Pollack’s The Yakuza, an Americanized version of the already outmoded romantic treatment of the subject; and most interesting, a lengthy account by Kazuo Kasahara, written as the fourth film was in production, in which he goes into detail about the difficulties involved in turning chaotic, decades-spanning events into a series of manageable screenplays.

Although the new edition is obviously technically superior to the Homevision DVD set, I’ll be holding on to that as it has a whole different collection of extras.

_______________________________________________________________

(1.) The best of these is Swords of Vengeance (1978), Fukasaku’s version of the oft-filmed 47 Ronin; typically this story is presented as a paean to loyalty and the nobility of sacrifice, the essence of the traditional samurai ethos, but Fukasaku deconstructs the story and ultimately presents the final battle not as the fulfillment of the samurai code but as a senseless explosion of violence which achieves nothing. (return)

Comments