More from Twilight Time

I still haven’t caught up with watching all my Twilight Time disks, including some backlist titles (Paul Greengrass’ Resurrected, Otto Preminger’s Bonjour Tristesse) and more recent releases (Yoji Yamada’s The Little House, John Huston’s Fat City and Shinji Aramaki’s Harlock: Space Pirate). But in the past few weeks, I have watched three of the newer ones.

*

Mysterious Island (Cy Endfield, 1961)

Actually, Cy Endfield’s Mysterious Island (1961) is an “encore edition”, essentially the same transfer as an earlier release, but with a few extras added. These are a brief older video featurette with Ray Harryhausen talking about the production and the effects work he did for it; an odd promotional short made at the time of the film’s release which throws in a bunch of disconnected facts about geography, geology, anthropology, zoology and history to support the movie’s fantastic elements; and a commentary by Randall William Cook, C. Courtney Joyner and Bernard Herrmann authority Steven C. Smith.

Mysterious Island was one of those rare occasions when producer Charles Schneer hired decent writers (John Prebble and Crane Wilbur) and a real director (Cy Endfield, who three years later collaborated with Prebble again for Zulu) to provide support for Harryhausen’s effects work, making it, along with First Men in the Moon, one of the best films of the animator’s career. Even so, this sequel of sorts to 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea reveals a much less lavish budget than that of Disney’s classic. The cast is acceptable, but far less distinguished, and the scale is noticeably smaller.

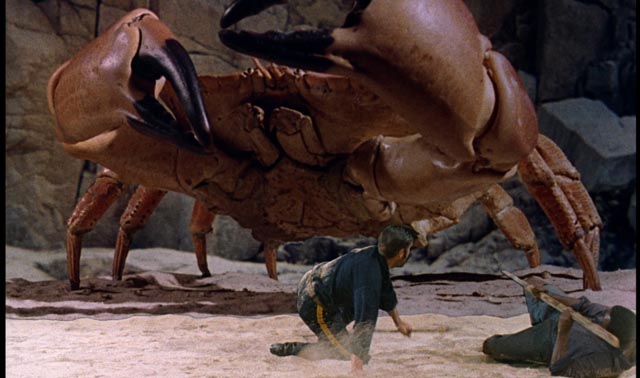

Still, there are visually striking moments, with some quite beautiful matte paintings, and Harryhausen’s animation set-pieces, judiciously spaced throughout, are well staged. If anything, they are more impressive than some of his more famous fantastic sequences (the skeleton fights in Seventh Voyage of Sinbad and Jason and the Argonauts, for instance) because here he is giving life to recognizably realistic animals – giant crab, giant bird, giant bee – which the viewer’s eye is more likely to find fault with because of their familiarity.

The story itself is, to put it mildly, rather spare. A small group of men escape from a Confederate prison in an observation balloon towards the end of the Civil War and are carried by a vast storm all the way across the continent and out over the Pacific, where they finally crash land on what seems to be a deserted island. There, they find a couple of shipwrecked women and encounter giant freaks of nature, which eventually turn out to be the result of experiments conducted by Captain Nemo in his quest to end war by creating a more than adequate food supply for the human race. Alas, a volcano finally erupts and wipes away Nemo and his scientific secrets.

The cast is better than usual for a Schneer-Harryhausen production, with Michael Craig, Michael Callan and Gary Merrill doing solid, no-nonsense work as the primary adventurers. The inimitable Joan Greenwood adds a genuine touch of class as the stranded Lady Mary Fairchild, and Beth Rogan (who died just a few months ago and was reputed to be the model for Julie Christie’s character in Darling [1965]) is very appealing as her niece Elena. Herbert Lom, more low-key than James Mason in the Disney film, projects authority as the outcast idealist Nemo.

The enthusiastic commentary provides a great deal of information on the production and the careers of the filmmakers, discussing the advantages and disadvantages of Harryhausen’s one-man-band approach to the effects, the huge contribution made by Cy Endfield both to the script and the staging, and the equally important role played by Bernard Herrmann, who took even these low budget fantasies seriously and wrote rich and powerful scores which made such films seem far bigger than they actually were.

The transfer is impressive, with rich colours and a nice degree of film grain, but as with pretty much all films of this type, hi-def is a mixed blessing. The greater degree of detail is problematic with older optical effects, revealing the inevitable degradation resulting from the multiple generations involved in compositing the many layers of image – live action, matte paintings, miniatures and animation. For those of us who love these films (and grew up when these techniques were the pinnacle of effects technology), all these signs of the labour involved are cherished as much as the end result, but I suspect that audiences raised on slick CGI effects might be troubled by the apparent “crudity”. It’s a little sad to think that something like Mysterious Island, a rousing kids’ adventure made with energy and imagination, might now be looked at largely as a historical artifact.

*

The Detective (Gordon Douglas, 1968)

This, of course, is the fate of many movies. Some are so much of their time that they are unable to escape it, while others for ineffable reasons transcend the era of their making even when firmly rooted in that time (will Casablanca ever “get old”?). But while some artifacts retain little interest (who today would want to sit through one of Paul Muni’s many biopics from the ’30s?), others remain fascinating for what they say about the past. Case in point, Twilight Time’s new Blu-ray edition of Gordon Douglas’ The Detective (1968). Douglas had a fifty year career in Hollywood, but even with almost a hundred directing credits listed on IMDb, his work reveals little personality. He was generally workmanlike, at his best competent, but as often as not rather dull and even clumsy. He made comedies, westerns, adventures, thrillers … but really only one title stands out: Them! (1954), the finest giant-bugs-created-by-nuclear-testing movie ever made. It’s tempting to see the success of this classic as deriving paradoxically from Douglas’ rather plodding lack of imagination. The monsters are treated in an effectively naturalistic, unsensational way, giving the film a degree of realism too often lacking in the genre.

That same plodding approach is what makes The Detective interesting. Adapted (by the always issues-oriented Abby Mann) from an ambitious novel by Roderick Thorpe, the film is packed with lurid, sensational, perverse elements which it strangely glides over without much emphasis. Made during the upheavals in the movie business which saw the collapse of traditional Hollywood self-censorship and the fraying power of the studios to impose their view of entertainment on a rapidly changing audience, The Detective is obviously a very self-conscious attempt to offer “adult” entertainment (not in the porn sense, but as a hard-hitting treatment of sophisticated themes and ideas about sexuality).

Frank Sinatra plays Joe Leland, a New York City cop with a conscience, who is called in at the start of the movie to deal with a particularly brutal murder. The victim was a wealthy gay man, stabbed and mutilated by an obviously unhinged assailant. Suspicion immediately falls on his “roommate” Felix (Tony Musante), who has disappeared. The investigation takes the detective into the city’s gay underground … or rather, the strange Hollywood version of that world. This was before Stonewall and the beginning of the long process of the normalization of homosexuality. Homosexuality in The Detective is still viewed as an aberrant psychological deformity and the film is packed with often grotesque stereotypes which at times tip way over into camp absurdity.

But what marks the movie as an interesting transitional artifact is the empathy Sinatra’s detective shows for these “deviants”, his belief that they’re just as human as anybody else; an attitude which stands out starkly against the prejudice and rampant homophobia of the other cops. In its way, The Detective tries hard to be a plea for understanding, even as it distorts the people it wants us to understand.

Parallel to the investigation (which is handled fairly perfunctorily), we get Leland’s personal life through flashbacks and conflicted scenes with his estranged wife Karen (Lee Remick). The couple’s marriage has failed because Karen is a self-diagnosed nymphomaniac who, although she loves Joe, just can’t stop herself from having sex left and right with any stranger who happens along. It’s a thankless role, but Remick as always lights up the screen when she appears and manages to make something sympathetic out of this caricature.

The flashbacks, always signaled by a move in to an enormous close-up of Sinatra’s blue eyes and a long dissolve, are clumsy and poorly integrated, repeatedly interrupting the narrative momentum. These diversions to Leland’s personal drama are perhaps a reflection of the literary pretensions of the novel, trying to make the story something more than a simple police procedural … but Sinatra is way too old to be convincing as the young cop in uniform who meets, courts and marries Remick at some point in the past. (According to the commentary track on the disk, the flashbacks in the novel – which is set in a smaller city, with the protagonist a private eye – sketch in Leland’s experiences during World War Two rather than his marital issues.)

While The Detective looks ahead to the cynical-cop-working-against-the-system of Dirty Harry, Serpico and their kind, its rather dire portrait of homosexuality (not surprisingly, the extreme violence of the murder is the work of a self-loathing gay man fighting against his own despised nature) and Gordon Douglas’ generally artless direction trap it in the moment of its making; its stereotypes are uncomfortable to watch even as the tentative effort to open up a discussion of a previously forbidden subject seems daring for a film starring someone of Sinatra’s stature.

The Blu-ray image has an effectively murky look in keeping with late ’60s cinematography and the sordid subject matter. On the commentary, Twilight Time regulars Nick Redman and Lem Dobbs are joined by David Del Valle, whose presence in the lively conversation puts the emphasis more on Frank Sinatra and his career than Douglas and the filmmaking, although that ground does get covered too. No one has much to say in favour of the director’s work, but they do a good job of parsing the film’s sexual politics. (Although Del Valle does possess a huge amount of knowledge about stars and celebrities, he has an annoying habit of making extraneous negative remarks about movies at best tangentially connected to the subject at hand, such as a snide comment here about Jack Gold’s The Medusa Touch, which he has never seen and which is much better than its reputation, simply because Remick co-starred in it.)

*

Scorpio (Michael Winner, 1973)

It didn’t take long after the international success of James Bond – with three hits in a row from 1962 to 1964 – before a kind of anti-Bond genre appeared, countering the glamour and the fantasy super-villains with a grimier, more compromised view of spies. Michael Caine’s Harry Palmer, who first appeared in Sidney Furie’s The Ipcress File (1965), was the opposite of Bond, a somewhat crude, cynical, working class agent with little respect for his bosses. That came out the same year as the more realistic, also very cynical, The Spy Who Came In From the Cold. As the ’60s continued in a turmoil of war and social unrest, although Bond continued to ply his glamorous trade, bleak cynicism was firmly entrenched in Cold War thrillers like the underrated A Dandy In Aspic (1968), completed by star Laurence Harvey after the death of director Anthony Mann during production. By the end of the decade, cynicism had pretty much devoured every other element of the espionage narrative … it’s the raison d’etre of John Huston’s The Kremlin Letter (1970) and Peter Collinson’s Innocent Bystanders (1972).

And yet, by 1973 this bleak genre seemed all but played out. Case in point, Michael Winner’s Scorpio, a thriller made with some polish and featuring an impressive cast headed by Burt Lancaster, Paul Scofield and Alain Delon, with fine support by John Colicos, Lloyd Bochner, J.D. Cannon, James B. Sikking, Joanne Linville and Gayle Hunnicut. But the script by David W. Rintels and Gerald Wilson can’t even muster the energy to motivate all the double crosses and betrayals. They merely exist as a given.

Lancaster is an aging CIA operative in Europe, in charge of arranging assassinations of inconvenient foreign dignitaries. Alain Delon is a hitman groomed by Lancaster. After their latest job in Paris, Lancaster heads back to the States, unaware that his protege was actually supposed to kill him as well. Why the CIA boss (Colicos) is so determined to off Lancaster is never clear – it’s just that top espionage bureaucrats do that kind of thing to agents reaching the end of their careers. As Delon drags his heels, other anonymous operatives are sent to finish the job, managing only to provoke Lancaster’s ire – particularly after they senselessly murder his wife. The story essentially runs around in circles, never going anywhere because there’s nowhere for it to go. It simply exists to reaffirm that the hidden world of espionage is morally bankrupt … suggesting by default that the assassin Lancaster is the most decent man among them.

Made immediately after The Mechanic, and just a year before Death Wish, Scorpio shows once again that Winner was quite capable of efficiently crafting a thriller even when there was no point to it. As an indication of just how aimless it all is, the movie is named for the underdeveloped Delon character (it’s his code name) rather than for Lancaster’s Cross, even though the French hitman plays a very secondary role in what story there is. I guess it just sounded cooler.

Although Scorpio is less engaging than some of Winner’s other movies, the disk features an excellent commentary track with Redman, Dobbs and Julie Kirgo in which Winner is afforded a re-evaluation as a distinctive maker of mid-level programmers in the years before the business began demanding that everything needed to be a bloated blockbuster. In particular, his talent for casting is recognized (his films from this period are packed with actors who were just at the start of big careers). The three commenters also delve amusingly into the director’s legendary self-mythologizing. It’s a refreshing listen, particularly since Winner is still often casually and erroneously dismissed as a completely talentless hack.

Comments