Two more British Films from Network

Last week I mentioned Network’s ambitious project to make available a vast array of movies on disk. As their “mission statement” puts it:

“Monthly from April 2013 Network begins an ongoing programme of releases featuring titles from every possible genre, selected from over eight decades of British film and covering such studios as Gaumont-British/Gainsborough, Ealing, London Films, British Lion, Rank and EMI, among others.

“With between five and ten new titles per month, this range will see the commercial release of many films unseen since their original theatrical screening. By including these rarities alongside more popular titles, Network hopes to redress the balance of appreciation for the British Film as a whole.”

Given the state of the industry, and the perennial predictions of the demise of DVD and Blu-ray, this is a remarkably ambitious undertaking. As with the Warner Archive in the States, Network’s British Film series is making available large numbers of films which would seem to have little commercial value – numerous B movies focused on crime, minor melodramas, series comedies featuring vaguely remembered or all-but-forgotten performers. For people with a broad interest in film history, and not just admirers of the canon, this is a potential treasure trove.

No doubt many of these films will turn out to be dull and unimaginative, as so many formulaic B movies are, but the sheer volume of Network’s output is likely to turn up small gems which would otherwise have remained hidden. The two I wrote about last week – Peter Yates’ Robbery and Val Guest’s 80,000 Suspects – stand out as bigger-budgeted, prestige productions. The two I have just watched, released on DVD rather than Blu-ray, are smaller but, it turns out, no less interesting.

All Neat In Black Stockings (Christopher Morahan, 1968)

Christopher Morahan, with a long and very prolific career in British television, made only five theatrical features, the best known probably Clockwise (1986), starring John Cleese. His second feature, made towards the end of the Swinging Sixties, is a real oddity. I confess that as I watched it, I felt an almost continuous sense of irritation. It’s a film which on its surface appears to be one thing, and yet refuses throughout to supply what it seems to be promising. Part of this confusion may be due to memories of what came after it – in particular the series of “Confessions of” sex comedies starring Robin Asquith, launched in 1974 by Val Guest with Confessions of a Window Cleaner. In fact, it might almost be thought that Guest’s film was modeled on Morahan’s, yet simplifying the material to gratify a more conventional audience.

After all, All Neat In Black Stockings concerns the activities of a sexually active, amoral window cleaner named Ginger played by Victor Henry, whose short career in film and television lasted less than a decade and ended long before his early death at 42 in 1985. The opening sequence cues us to expect a teasing, voyeuristic comedy with Ginger climbing about the outside wall of a hospital as he pursues a nurse going about her duties inside. He makes a date with her before being kicked out by the matron, and takes her back to his rundown room where, with the lights out, he slips next door to change places with his best friend Dwyer (Jack Shepherd). These two make a habit of sharing their disposable sexual conquests (not to mention each other’s possessions and clothes), showing little actual interest in any of the women involved – a fact which suggests a subtext the film never explores.

Given the initial set-up, the viewer is cued to read all this as comedy; but given our more enlightened view of gender relationships today, it doesn’t play as funny. There’s nothing endearing about the rampant egotism of Ginger. So when he meets and apparently falls for Jill (19-year-old Susan George), my reaction wasn’t so much a hope that things might work out for the couple as it was a desire to yell at her to get the hell away from him. But then, somewhere around the halfway point, doubts began to creep in about the film’s agenda. And it gradually grows darker.

What happens to Jill is a direct consequence of Ginger’s callous lifestyle and his relationship with Dwyer. His subsequent decision to be “generous” to her merely guarantees her continued unhappiness. What began as a story which suggested that this waster might be reformed by discovering authentic love, heads in the opposite direction; he doesn’t change and it becomes more obvious that his egotism results in pain and damage to the people around him. The casualness of the early sexual escapades takes on a bleaker appearance as the film lays out in greater detail the consequences for the women he victimizes.

In the end, although the character remains the same, and even the final scene is shot as if it belongs in a lightweight sex comedy, it turns out that All Neat In Black Stockings is determined to expose the dark side of the Sixties’ sexual revolution. Even now, I’m not sure how much of the film’s impact is intentional and how much inadvertent. Based on a novel by the innovative, award-winning fantasy writer Jane Gaskell (who co-wrote the script with Hugh Whitemore), it subverts the narrative expectations it initially sets up, but it does this in such a way that the viewer (at least this one) feels himself to be fighting against what the film seems to be showing. Only in retrospect, does its critical purpose come into focus. It’s like being offered a sugary pastry only to discover that it’s filled with terribly bitter cream. That bitterness may well be a proto-feminist critique of the ways in which the sexual revolution of the Sixties turned out to be more to the advantage of irresponsible men than liberating for women.

The cast is good, even if many of the characters are not particularly likeable. Although Susan George had been working in film and television since the age of 12, this appears to have been her first major role and she plays Jill with a fragile charm which just makes Ginger seem an even bigger arsehole than Victor Henry’s gratingly energetic performance initially projects.

Network’s DVD offers two versions of the film: the default is a 1.75:1 image, while the special features include an open-matte 1.33:1 alternative. The image is bright although the colours tend to be a bit washed out. The sound track is generally clean and clear, though the lack of subtitles might be a drawback for some viewers given the characters’ accents. The only other extras are a brief extended scene without audio, a trailer, an image gallery and promotional pdfs.

West 11 (Michael Winner, 1963)

Coming closer to the start of the decade, and following a handful of minor B movies and comedies, Michael Winner made the first of a string of films which mark the most interesting, if not the most commercially successful, period of his career. Although best known for his thrillers starring Charles Bronson, he began here with some finely observed stories of contemporary English life. Immediately after West 11, he made The System (1964), the first of four films starring Oliver Reed, and West 11 is every bit as good.

Based on The Furnished Room, a novel by Laura Del Rivo, and scripted by Keith Waterhouse and Willis Hall, the prolific team responsible for Whistle Down the Wind, A Kind of Loving and Billy Liar among many others, West 11 is a stark drama about Joe Beckett (Alfred Lynch) a man who has lost his faith (formerly Catholic) and sense of purpose. He’s in a relationship with a woman named Isla (Kathleen Breck), who seems driven to test him by flaunting her faithlessness even as she seems unable to detach herself from him. Set in a London of boarding houses, cafes and seedy pubs, the novel has been compared to the work of Patrick Hamilton and Winner’s film captures much of the flavour of Hamilton’s acutely observed work.

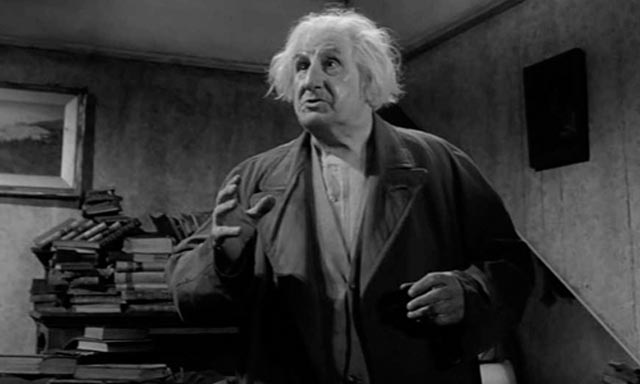

Joe seems helpless in the face of existential despair. At the start of the film he packs in a mindless job as a sales clerk in a men’s clothing store. He can’t pay his rent. His ailing mother comes to visit and she can’t conceal her disappointment in his aimlessness. Isla tells him she’s had sex with another man and the ensuing argument gets him evicted. He needs to do something, anything, to confirm that he’s alive … and so falls prey to a shady character named Dyce (Eric Portman) who keeps turning up and dropping hints about easy money to be made.

Dyce has a wealthy aunt who lives in a remote country house and he’s hatched a plan to get his inheritance ahead of time. Echoing the deal proposed by Bruno in Patricia Highsmith’s Strangers On a Train, he believes that a completely random stranger could get away with murder. All he needs is someone like Joe to fake a burglary and bump the old woman off. With everything else in his life falling apart, Joe eventually agrees. What happens at the country house is steeped in irony, with Joe unable to go through with the plan but nonetheless exposed through a fatal accident.

West 11 is beautifully directed by Winner, with strong performances and evocative cinematography by the great Czech cameraman Otto Heller who had previously shot such signature works as Thorold Dickinson’s The Queen of Spades, Robert Siodmak’s The Crimson Pirate, Alexander Mackendrick’s The Ladykillers, Laurence Olivier’s Richard III, Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom, and Basil Dearden’s Victim. I include this long list to reinforce the idea that Winner, who became a figure of contempt in his later career, began as a serious filmmaker working with major collaborators. He also possessed a fine sense of casting, with small roles here filled by the likes of David Hemmings, Francesca Annis, Patrick Wymark, even Mike Leigh in an uncredited bit before he began directing. In larger roles, Portman stands out as the oily Dyce, with Diana Dors, Kathleen Harrison, Freda Jackson and Finlay Currie adding texture to the film’s portrait of London on the brink of turbulent transformation.

The 1.66:1 black-and-white image on Network’s DVD is excellent, with good contrast and a film look which shows the London locations to good advantage. Like 80,000 Suspects, this film came at the tail end of black-and-white and makes the wholesale switch to colour seem regrettable. Existential bleakness always looks better in black-and-white.

Extras consist of a couple of alternate scenes for the export version, a theatrical trailer, image gallery and promotional pdfs.

Although I personally don’t have much interest in the resurrection of long forgotten comedians in low-budget quota quickies, I and no doubt many others will continue to be grateful if Network’s efforts unearth more films like these two and the pair I wrote about last week.

Comments