Criterion Blu-ray review: Whit Stillman’s Barcelona (1994)

Whit Stillman has a new film coming out this year. Love & Friendship, just his fifth feature in twenty-six years, is adapted from a Jane Austen story. Given the cultural specificity of his previous films, all of which focus on intensely self-aware members of what, in his first feature, Metropolitan (1990), were termed the “urban haute bourgeoisie”, this might seem like an odd departure. And yet, those previous films actually share much in common with Austen: they all deal with minutely observed social details of the lives of their privileged characters. But more, beneath the surface of self-possession and verbal dexterity, there are deep currents of insecurity. Like so many of Austen’s characters, the young people in Stillman’s films are almost desperately trying to stay afloat in a material world which does not guarantee their survival in the manner to which they have been accustomed since birth.

In the triptych (Stillman’s word) of films beginning with Metropolitan, Stillman dextrously sketched a portrait of a generation of Americans trying to find their way out of childhood and into adulthood. Although the social details were finely observed, Stillman wasn’t exactly a realist. These characters were all hyper-verbal, endlessly defining and redefining themselves through their talk. In this, he most resembles someone like Oscar Wilde. The films are packed with a wit and humour which emerges as a strategy to stave off fear and uncertainty.

The three films were made out of chronological order, beginning with Metropolitan (depicting the last official year of childhood for a group of kids steeped in literature and philosophy, but not so much the realities of life) and ending with The Last Days of Disco (1998, dealing with a group of young adults striving to enter life in the world of publishing as the heyday of New York club life was waning in the later ’80s). The final film in the sequence, Barcelona (1994), was actually the second to be made; in terms of its narrative canvas, it is the biggest of the three, and in a number of ways it is also the most problematic.

Set in the Spanish city of the title, Barcelona deals with the life of two American cousins abroad in what an opening title informs us is “the last decade of the Cold War”. For viewers familiar with Stillman’s previous features, an unsettling note is immediately introduced as the film begins with the explosion of a terrorist bomb. The lingering impact of this event creates a strange effect when we are quickly introduced to our protagonist, Ted (Taylor Nichols), through a lengthy voiceover rumination on his attempts to figure out the nature of romance and his position in relation to all the attractive Spanish women who surround him in the city. His struggle to find a way to protect himself from disappointment and rejection (essentially by determining to be attracted only to plain or homely women) has all the amusing verbal dexterity we expect from Stillman, and yet this takes place in an environment which is not merely uncertain (like the New York of the other two features), but is actively hostile to Ted and people like him – that is, to Americans.

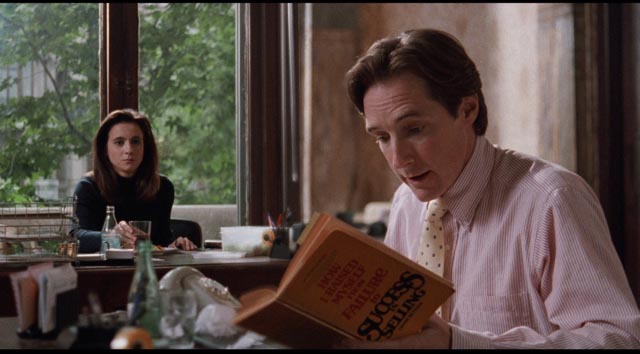

When Ted’s cousin Fred (Chris Eigeman) arrives unannounced and moves into Ted’s flat (“just for a few days”), the film begins to operate on several interconnected levels. There’s the lifelong competition and friction between the two of them going back to certain childhood incidents, continually exacerbated by Fred’s habit of telling everyone they meet (that is, women) all kinds of made up secrets about Ted involving perverse sexual predilections, things which he blithely says are intended to make Ted “more interesting” to potential partners, but which in reality continually undermine Ted’s already uncertain confidence.

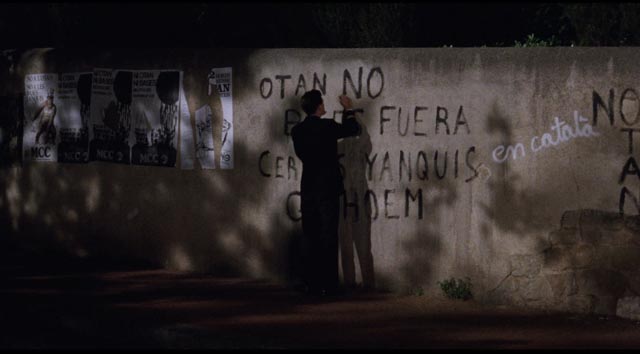

Woven through the body of the film, which deals with the pair’s romantic and sexual adventures with a number of Spanish women – who are far less inhibited than the Americans – is a more troubling thread: the city is rife with anti-American feeling, and Ted and Fred find themselves continuously being defined not by their perceptions of themselves, the characters they try to project, but rather by political factors rooted in a hostility towards American foreign policy and a European perception of U.S. imperialist violence around the world. This is heightened by Fred’s position as a U.S. naval officer, in Barcelona as a kind of advance man before the arrival of the Mediterranean fleet for a visit.

And so although Barcelona is most definitely a romantic comedy – and a comedy of conflicting manners, with Ted and Fred pairing off in various ways with Marta (Mira Sorvino), Montserrat (Tushka Bergen), Greta (Helena Schmied) and Aurora (Nuria Badia) – it is also a dissection of the limitations of this pair who, with their assurance about their identities as Americans and the unquestionable value of being American, stumble blindly into dangerous waters. Ted, a salesman for some unspecified corporation, represents the economic arm of U.S. interests, while Fred obviously stands in for U.S. military interests. Neither is particularly aware of the power they symbolize; in fact for Fred international relations seem like nothing more than a game, his own egotism clouding awareness and judgement. The cousins continually cause offence by merely being who they are, while Fred’s penchant for making things up for dramatic effect leads to an inevitable yet nonetheless shocking moment which ruptures the generally light tone of the film.

To be honest, I’m not sure whether it’s the change of setting, removing these characters from their natural environment in the States, or whether it’s the conception of the characters themselves, but I find that Ted and Fred are frequently irritating – Fred for his continuous manipulation and cheerful abuse of Ted, and Ted for his meek acquiescence to that abuse. Stillman seems to be depicting an almost cliched image of Americans abroad, the kind of image many Europeans hold of Americans as both naive and arrogant, politically and culturally. This underlying irritation works against the surface romantic comedy, making it difficult to understand why sophisticated, self-possessed Spanish women would want to become involved with the pair, let alone end up marrying them and moving to the States (where at the film’s end a tasty barbecued hamburger comes to represent the superiority of the U.S. to politically troubled Europe).

While it was possible to empathize with the characters of Metropolitan and The Last Days of Disco and their efforts to define themselves and find a place in the world, Barcelona reveals the limitations of these “urban haute bourgeoisie” when they travel outside their own environment into a larger world. Even though the film, through its romantic entanglements, seems critical of the moral and political attitudes of the Europeans, what is finally revealed is the inadequacy of Ted and Fred to deal with a culture beyond their own.

Although I find the film’s conception problematic, there’s no denying that John Thomas’ cinematography is excellent, providing a vibrant portrait of the city which for the most part avoids focusing on touristy sights. The cast is very good, skillfully handling the dense dialogue, while Stillman directs with a light touch despite the heavier elements of the script. In fact, Barcelona has many amusing scenes and strangely they linger in my mind even as the irritation I felt while actually watching the film fades … like returning from a trip and recalling the sights, while gradually forgetting just how annoying your companions had been.

The disk

Criterion’s Blu-ray edition, released as a stand-alone disk simultaneously with their box set of the triptych, displays a vibrant 2K transfer from the original negative. The stereo sound track, mastered from original 35mm magnetic tracks, strongly supports the almost non-stop dialogue, with appropriate ambiances and Mark Suozzo’s score adding texture.

The supplements

As expected, Criterion support the film with a number of extras, beginning with a relaxed commentary from director Stillman and his two stars, Taylor Nichols and Chris Eigeman, which covers both the logistical issues of shooting in Barcelona and the themes Stillman was trying to get across.

Farran Smith Nehme provides a video essay (20:50) dealing with all three films, noting that the air of privilege enjoyed by the characters is somewhat illusory, and that while there may be a satirical note running through Stillman’s work, he treats all his characters with empathy rather than irony, and certainly without condescension. The Making of Barcelona (5:31) is a brief promo piece from 1993 about the location shoot. A clip from the Today show in 1994 (5:08) has Katie Couric asking a seemingly uncomfortable Stillman whether the success of his first film made it difficult for him to make a second. Stillman’s appearance on The Dick Cavett Show in 1991 (24:31) deals with Metropolitan and his future plans, and would seem more appropriate to Criterion’s Metropolitan disk than here. Then there’s an appearance by Stillman on the Charlie Rose show from 1994 (13:31) promoting Barcelona.

There are four very brief deleted scenes (2:52) and an alternate ending (4:25), the latter reintroducing the element of political violence to disrupt the resolution of the romantic comedy. Stillman, Nichols and Eigeman provide optional commentary on these. Lastly, there’s a trailer (1:44), and a booklet with an essay by film scholar Haden Guest.

Comments