Mining a shrinking vein: The Vincent Price Collection III

There are often diminishing returns when it comes to the release of a series of themed box sets. The first usually contains the best work available – as with various Fox and Warner noir collections – with lesser works turning up in the later sets. And yet pleasures may still be found as lower limits of the barrel are scraped. These pluses and minuses are fully apparent in Shout! Factory’s third volume of The Vincent Price Collection. The first two sets contained all the major AIP/Corman horrors, along with such signature works as the Dr. Phibes films and Witchfinder General. Still missing in action is my favourite Price film, Douglas Hickox’s Theatre of Blood (though that is available on an excellent region B Blu-ray from Arrow).

The new set offers four movies (five, if you count both versions of Gordon Hessler’s Cry of the Banshee), plus a 53-minute made-for-television one-man show with Price performing a handful of Poe short stories. Surprisingly, it’s this last which turns out to be the star of the set in terms of the quality of Price’s work.

*

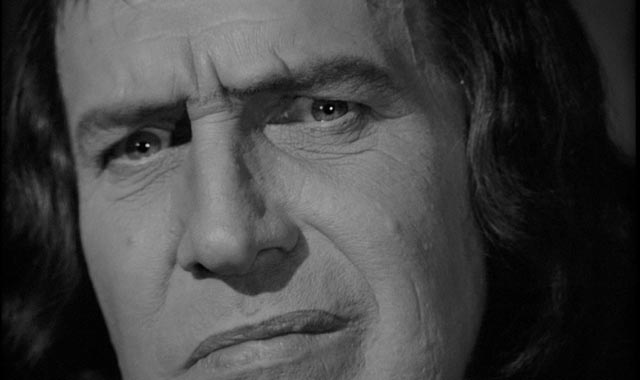

Tower of London (Roger Corman, 1962)

Tower of London (1962), the sole Corman-directed title in the set, is a bit of an oddity. Although this followed the first four Poe features, it was not made for American-International, but rather Admiral Pictures and executive producer Edward Small, and shortly before shooting began Corman was told that his historical drama would have to be shot in black-and-white. He and his regular designer Daniel Haller were disappointed, but I think in the end this benefited the picture (creatively, though not commercially) by giving it a gravity which may have been undermined by Haller’s usual colourful studio sets.

Not exactly horror, this retelling of the story of Richard III and his violent plans to usurp the throne – which involved a good deal of murder – is fast-paced and energetic, and the script by Leo Gordon, Robert E. Kent and Amos Powell, while not exactly Shakespeare, does provide Price with a terrific villainous role to tear into. He obviously relished the opportunity and the film plays almost like a dry run for his greatest performance as Edward Lionheart, the murderous Shakespearean actor in Theatre of Blood.

As history, the movie is no more accurate than Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of King Richard III, but it’s refreshingly devoid of the stuffiness which so often plagues costume dramas. Although something of an orphan, standing as it does outside the Corman/Price/Poe canon, it deserves to be better known. Its presence in the new set, in an excellent transfer from a fine grain print, will perhaps aid in boosting its reputation.

The disk includes a number of extras, including brief interviews with director Roger Corman and producer Gene Corman, a trailer, and (in standard definition) two episodes of Science Fiction Theatre, a series from the mid-’50s, both starring Price: One Thousand Eyes and Operation Flypaper. These are little more than curiosities, hampered by the budgetary and technical limitations of the period.

*

Diary of a Madman (Reginald Le Borg, 1963)

I’ve previously written briefly about Diary of a Madman (1963), an adaptation of two Guy de Maupassant stories also produced by Edward Small and co-produced and written by Robert E. Kent. Although the hi-def image here is naturally a vast improvement over the copy I watched on YouTube, the film’s flaws remain apparent. Directed with little sense of style by the prolific but undistinguished Reginald Le Borg and designed by Daniel Haller, the film is over-lit by the equally prolific Ellis Carter (who did a lot of genre work in the ’50s, including two big favourites – The Incredible Shrinking Man and The Monolith Monsters, just two of eight credits from 1957). Diary of a Madman is very colourful in HD, but not terribly atmospheric.

Watching it again, and doing my best to set aside its major distortion of the source stories, I have to say that it is quite entertaining and Price does well as the magistrate tormented and driven to murder by an unseen being called the Horla, which seems to have no other interest than making life hell for randomly chosen people. A minor work in Price’s career, it’s interesting to imagine what Corman might have made of this with his greater attunement to the psychological derangement of characters like Magistrate Cordier.

The sole extra here is a commentary from film historian Steve Haberman, who also comments on two more of the set’s titles. While he obviously has a lot of background knowledge, he tends to oversell the film in a way which, in me at least, provokes a reaction which just amplifies my own reservations about it. He also, in passing, dismisses Tower of London as a disaster, which it most certainly isn’t.

*

An Evening of Edgar Allan Poe (Kenneth Johnson, 1970)

Kenneth Johnson’s An Evening of Edgar Allan Poe (1970), made for television but financed by American-International, is a showcase for Price, who delivers four of Poe’s stories as lively monologues on appropriate sets. The first and last, The Tell-Tale Heart and The Pit and the Pendulum, presenting as they do protagonists pushed to the limits of their sanity, allow the actor to emote at full-bore; the first is set in a stark tenement room, while the second is rather overloaded with video effects which strive to increase its scale but rather serve as a distraction. The second act, based on a brief story called The Sphinx, is little more than a protracted joke, but the third and best act not only provides Price with his meatiest role in the piece, it’s also the best directed and edited of the four.

The Cask of Amontillado, a story of sadistic revenge, is recounted years after the fact by Montresor over a candle-lit dinner, with the audience present in the role of a friend to whom he feels free to tell of his crime. For some unspecified reason Montresor developed a furious hatred of another nobleman, Fortunato, and devised a plan to use the man’s love of rare wines to lure him into a catacomb and seal him up alive behind a wall. This story was played for laughs by Corman in Tales of Terror (1962), with Peter Lorre as Montresor and Price as Fortunato; but here Price plays both parts in his recounting of the event, creating two different personalities subtly aided by careful lighting and editing, and it becomes a chilling portrait in egotism and gloating sadism.

Director and co-writer (with David Welch) Kenneth Johnson gets a featurette on the disk in which he describes the origins of the project and his relationship with Price, while Haberman’s commentary focuses on the life and work of Poe.

*

Cry of the Banshee (Gordon Hessler, 1970)

An Evening of Edgar Allan Poe falls between the second and third features that Price made with Gordon Hessler, Scream and Scream Again and Cry of the Banshee (both also 1970). The latter is featured in Shout! Factory’s set in both Hessler’s original cut and the altered producer’s cut which became the release version. Working once again with writer Christopher Wicking (who here rewrote an original script by Tim Kelly), Hessler tackles material similar to Michael Reeves’ Witchfinder General (1968), the pathology of witch-hunting and superstition, which would also turn up in Michael Armstrong’s Mark of the Devil (1970) and Piers Haggard’s Blood on Satan’s Claw the following year. Hessler’s film is the least of these four, but not without interest.

While in Witchfinder General and Mark of the Devil all intimations of the supernatural are mere delusion, signs of pathology in those who are determined to root out heresy, and in Blood on Satan’s Claw the Devil is very real, in Cry of the Banshee the supernatural is treated more ambiguously. There are witches, but they are adherents to an older pagan religion which the magistrate Lord Edward Whitman (Price) holds in contempt as the delusion of uneducated, superstitious fools. Nonetheless, in his view they are an offence to ordered society, and so he tries to stamp them out – by slaughtering many and telling the rest to go somewhere else. The massacre perpetrated by Whitman’s men, however, drives the leader of the witches, Oona (Elisabeth Bergner, whose career went back to Germany in the early ’20s), to call on the Christian Devil for help … in effect, Whitman’s abuse of these pagans actually triggers the evil he didn’t really believe in in the first place.

A shape-shifting demon (Patrick Mower, two years after The Devil Rides Out) infiltrates Whitman’s family and begins to destroy it from within. In typical early ’70s fashion, the film reaches a bleak climax. Also in typical ’70s fashion, there isn’t anyone in particular to root for here other than Whitman’s daughter Maureen (Witchfinder General’s Hilary Dwyer): Whitman himself is a sadistic, debauched nobleman; his wife Lady Patricia (Essy Persson) is rapidly slipping into madness because of his abuse; his victims are barely sketched in.

Although Hessler and Wicking were upset with the producer’s re-cutting of the film, which resulted in some significant restructuring of the narrative, I have to say the theatrical version makes a bit more sense as a story. In Hessler’s cut, the massacre of the witches comes about halfway through, but Patrick Mower’s demon is already working as a groom for the Whitman family, with a powerful hold over the weak and increasingly deranged Lady Patricia. In the theatrical cut, the massacre opens the film, with Oona immediately summoning the demon and sending him off to do harm to the Whitmans. Chronologically, this works much more effectively. But both versions are colourful, and effectively nasty, with the nudity and violence being much reduced in the theatrical cut. The biggest loss in the producer’s cut, however, is the replacement with static titles of the distinctive animated title sequence created by Terry Gilliam for the director’s cut.

The disk includes an interview with director Hessler, who says that he and Wicking were trying to subvert standard horror film elements in this and their other collaborations. Although I quite like Hessler’s work (particularly the deranged Scream and Scream Again), I don’t think the works themselves support his stated ambition. Steve Haberman in his commentary, however, once again over-praises, here seeing in Price’s Lord Edward a more complex and disturbing character than the witchfinder Matthew Hopkins. To me, the character’s shifts from sadistic bravado to insecurity, from skepticism to reluctant belief, seem more like uneven writing than nuance.

*

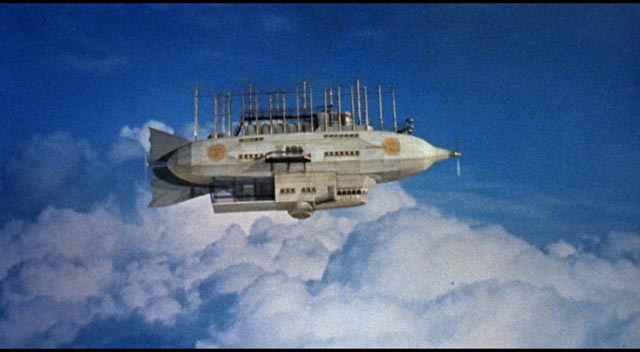

Master of the World (William Whitney, 1961)

The “biggest” film in the set is also the worst. Master of the World (1961) was American-International’s attempt to cash in on the success of Disney’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954) and Mike Todd’s Around the World in Eighty Days (1956) with their own Jules Verne adaptation. Unfortunately the company had only a fraction of the resources needed to handle an effects-laden period epic. To compound the budgetary limitations, A-I hired B-movie and television director William Whitney to direct. The idea may well have been that he would bring some kind of no-nonsense efficiency to the project, but the downside was that the movie lacks any sense of style.

In a story adhering quite closely to the 20,000 Leagues template, a small group of adventurers find themselves trapped aboard a futuristic (for the 1800s) machine built and controlled by a visionary scientist bordering on megalomania who is determined to end war by beating it out of stubborn mankind. The Nemo surrogate here is Robur (Price), an inventor who has built the Albatross, a massive airship which bears a vague resemblance to a flying Nautilus. The adventurers are the crusty arms manufacturer Prudent (Henry Hull), his argumentative associate Phillip Evans (David Frankham), his daughter Dorothy (Mary Webster), and rugged government agent John Strock (Charles Bronson).

Scriptwriter Richard Matheson tries to fill the threadbare film with conflict and incident, but there isn’t much story. Evans is an irritating hothead who thinks it’s better to die heroically than to formulate any effective plan to put a stop to Robur’s schemes (which involve dropping bombs on various armies and navies), making Strock’s job unnecessarily more difficult. It’s not surprising that Dorothy, who is Evans’ fiancee, becomes attracted to the agent.

Although the sets were designed once again by Daniel Haller, the interior of the Albatross is rather bland, while the underfunded effects work is generally unimpressive. When the Albatross flies over London, we get stock footage from the opening moments of Laurence Olivier’s Henry V (1944), complete with Elizabethan architecture and the Globe Theatre dominating the centre of the frame. When Robur bombs the navy, he blows up Elizabethan galleons. When he attacks a pair of warring armies, the stock footage is from Zoltan Korda’s The Four Feathers (1939). Even making allowances for the fact that the movie is aimed at 10-year-olds, this kind of carelessness shows a degree of contempt for the audience. Meanwhile Les Baxter works overtime to create an epic impression with his score, but the film remains pretty lifeless.

The one bright spot is the cast, even if the characters themselves are not that interesting. Price retains his dignity as Robur, Hull chews the scenery ferociously, and Charles Bronson goes about his heroic business with admirable seriousness. Frankham can’t seem to transcend his unevenly written part and Webster has little to do as the heroine, while Vito Scotti gets the thankless task of providing strained comic relief – repeatedly – as the ship’s cook.

An elderly David Frankham provides a charming commentary, reminiscing about the production and Price; he obviously had a fun time making the film and has fond memories of it. The disk also includes a feature-length interview with writer Richard Matheson, parts of which were previously sampled on several disks in The Vincent Price Collection II. In talking of Master of the World, he seems to take pride in having combined two Verne novels into this would-be epic, but also recognizes that the resources provided by American-International were hopelessly inadequate.

*

Although I enjoyed this third set in Shout! Factory’s series, I’m not sure there’s much left for a fourth set, although a region A edition of Theatre of Blood would be a good idea (note: Twilight Time have announced a Blu-ray release for later this year), along with a new hi-def release of William Castle’s The Tingler, Albert Zugsmith’s oddity Confessions of an Opium Eater and Jacques Tourneur’s disappointing final feature War-Gods of the Deep/City in the Sea … and for the true completist, the two Dr. Goldfoot “comedies”.

*

Postscript: Dragonwyck (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1946)

Right after watching The Vincent Price Collection III, I revisited Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s Dragonwyck (1946). This was Mankiewicz’s first film as director after a lengthy and successful career as a writer and producer and has often been dismissed as a “work for hire” which has little to do with the rest of his movies. He took it on for a number of reasons, despite not thinking much of the best-selling source novel by Anya Seton.

A Gothic romance centred on a young woman who comes to a large gloomy mansion and gets involved with a compelling but sinister older man, it quite obviously follows in the successful footsteps of Hitchcock’s Rebecca and Suspicion and other romantic thrillers of the period. Strangely, it was initially going to be the work of Ernst Lubitsch, the master of sophisticated comedies. When Lubitsch’s failing health got in the way, Mankiewicz eagerly took over, perhaps more for the chance to work with Lubitsch (as producer), whom he greatly admired, than from any real interest in the material itself. And yet Mankiewicz wrote an excellent script and directed with great sensitivity to his cast and a fine sense of atmosphere (aided by Arthur Miller’s excellent cinematography).

A couple of things distinguish Dragonwyck from many of the other romances of the time, starting with its attention to period and setting – the Hudson Valley in the 1840s. Woven through the film is a political element as oppressed farmers fight against a lingering Old World social order under which they are essentially indentured to their arrogant Dutch masters (the Patroons) who own all the land and demand rent and tribute in the form of a percentage of the year’s crops. This gave rise to what became known as the Rent Wars, in which the American concept of individual freedom and independence rose up against a residue of European feudalism. The power, arrogance – and eventual madness – of the charismatic anti-hero is firmly rooted in this social order. And the heroine’s gradual awakening to the unjustness of this order, which goes against the founding principles of the nation and her own beliefs which were formed on her father’s farm in Connecticut, is what causes the initial cracks in her romantic infatuation with the man she has married.

A second element, less well worked out, is a hint of the supernatural. Local legend has it that Dragonwyck is haunted by the ghost of an ancestor’s wife who was driven to suicide by her husband because she couldn’t produce a son … a foreshadowing of the current Patroon’s own mad obsession. This ghost manifests in the form of music played at night on the dead woman’s harpsichord, music which can only be heard by direct descendants of the line and which foreshadows some kind of doom. At this point in Hollywood history, it was more usual for supernatural manifestations to be explained away or played for comedy. Only Lewis Allen’s The Uninvited (1944) had previously played its ghosts straight.

Dragonwyck, produced by Fox, was conceived as a starring vehicle for Gene Tierney, who plays the farmer’s daughter Miranda Wells, and she makes for a very appealing heroine. But what makes the film most notable now is that it was stolen from its star by third-billed Vincent Price as Nicholas Van Ryn, the master of Dragonwyck, who coolly murders his first wife because she gave him only a daughter, and appropriates his distant cousin Miranda by playing on her naive, restless romanticism, for the sole purpose of providing him with a son and heir.

This is the film which forged Price’s inimitable screen persona, suave, articulate, brooding and touched with madness (and associated with a dead wife, a major theme in his work for William Castle and Roger Corman). Nicholas is an almost fully formed first draft of Roderick Usher from Roger Corman’s 1960 movie. Price’s presence is large and theatrical, but despite the accusations which would often be leveled at him, not in the least hammy. He was not a naturalistic actor, but the artifice was almost always, as here, perfectly controlled for maximum dramatic effect. Although his madness is only gradually revealed, there are subtle notes beneath his initial attractiveness which make the viewer uneasy as he draws Miranda in. It’s fascinating to see what had up until then been a fine character actor create here in this one film the distinctive persona which would make him one of the most recognizable stars of the next three or four decades.

Mankiewicz’s skill in casting goes beyond the leads to fill every supporting role with distinctive talent. Miranda’s parents are Walter Huston as the deeply religious farmer Ephraim Wells and Anne Revere as his wife Abigail, a strong and patient mediator between the stern father and his headstrong daughter. Vivienne Osborne could have been a mere caricature as Nicholas’ first wife Johanna, but turns this somewhat grotesque woman – desperate for her husband’s love and approval while concealing her knowledge of his contempt behind endless eating and phantom illnesses – into a touching and finally quite tragic figure. Connie Marshall as their daughter Katrine gives one of those creepily preternatural child performances which displays a disturbingly convincing awareness of emotional despair. Spring Byington and Jessica Tandy appear as two very different servants, Byington as Magda who rather gleefully recounts the family’s dark history to the newly arrived Miranda and Tandy as the sensitive and fiercely protective Peggy, whose crippled leg triggers a telling display of Nicholas’ intolerance for imperfection. Henry Morgan does well in his few scenes as a leader of the rebellious farmers, while future Amazing Colossal Man Glenn Langan has the film’s most thankless role as the decent doctor who tries to mediate between Nicholas and his tenants while quietly falling in love with Miranda.

Considering that Dragonwyck was Mankiewicz’s directorial debut, and so different from most of what was to come, it’s a remarkably assured piece of work and stands as a fine example of Hollywood period melodrama. But its chief value today lies in its revelation of a fascinating actor seizing a role and finding his lasting screen identity.

Comments