Recent discoveries on disk

In pre-home video days, it was easy for a movie which didn’t connect with an audience to get lost. One of the great benefits of home video is that it enables the rediscovery of some of these movies, which now, separated from their original time, can be seen and appreciated in ways their once-limited distribution prevented. In the past couple of weeks, I’ve watched three movies, of which two were previously unknown to me, while the third is by a director who, despite his stature, has gained little traction even on video.

The latter is Elio Petri, a major Italian filmmaker, of whose work I only know of four titles given a release on video in English markets. Still best known for the pop sci-fi satire The 10th Victim (1965, released on DVD by Anchor Bay in 2001, re-released by Blue Underground in 2009, and on Blu-ray in 2011) and his one real international success, Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (1970, released by Criterion in a dual-format edition in 2013), he got a boost two years ago when Arrow released his first feature, L’Assassino (1961), in a dual-format edition. And now I’ve just caught up with another of his films, surprisingly released as a burn-on-demand disk from the MGM Limited Edition Collection in 2011. Based on this small sampling, it’s difficult to form a clear image of Petri; although there’s an obvious Leftist critique of bourgeois society running through these films, there’s also a strong thread of self-reflexive cinematic play which removes the films from any kind of social realist tradition. But even The 10th Victim has some political undertones beneath its playful ’60s Pop Art surface.

A Quiet Place in the Country (Elio Petri, 1968)

A Quiet Place in the Country (1968) comes immediately before Investigation in his filmography, and it shares some stylistic similarities with that masterpiece as well as with Victim, with an opening visually very much of its time: we first meet the protagonist, painter Leonardo Ferri (Franco Nero), in a fetishistic situation, bound to a chair and surrounded by the detritus of consumer society while being sexually provoked by his agent/mistress Flavia (Vanessa Redgrave). Whether this is actual sexual play, or a subjective manifestation of Ferri’s sense of creative impotence in the face of rampant consumer capitalism isn’t entirely clear.

Although his work is in demand, Ferri has a serious case of creative block. He hates having to deal with galleries and art dealers and decides he needs to get out of Milan for some peace, quiet and isolation. Initially Flavia arranges for him to stay at the country villa of a patron, but it immediately becomes obvious that he’s expected to be a pet showpiece for the wealthy man to parade in front of his envious friends. On the way there, however, Ferri sees a large abandoned estate and he becomes fixated on acquiring it and moving in.

From here on, the film’s connection with reality becomes slippery as Ferri obsesses about the house and its history. Petri, who also co-scripted with Tonino Guerra and Luciano Vincenzoni, maintains a sense of ambiguity throughout – is Ferri slipping into delusional madness, or is he being plagued by ghosts as he “sees” events surrounding a crime committed during the war, the layers of which are gradually stripped away until the perpetrator is exposed … perhaps. Prefiguring the elusive, elliptical style of Investigation, Petri gives the film a shimmering surface which glides by while more unsettling undertones almost subliminally disturb the viewer. The lines between personal obsession and madness and the external dimensions of historical horror are blurred, calling into question the supposed detachment of the artist from the sordid realities surrounding him.

The MGM disk has a reasonably solid visual presentation, with bright colours and a fair amount of detail. There are two audio tracks, one an Italian dub with English subtitles, the other an English dub; interestingly, the English dub has a more pleasing sound – and it appears that Redgrave and Nero were speaking English on set and dubbed their own voices. There’s also a trailer which emphasizes the film’s hallucinatory mood.

*

Dragon’s Return (Eduard Grecner, 1968)

Although produced the same year, Eduard Grecner’s Dragon’s Return (1968), while made at the tail end of the Czech New Wave, just before the Soviet invasion, shows no signs of the European Modernism which suffuses Petri’s style. This stark black-and-white film, set in a kind of timeless past (without the historical specificity of Frantisek Vlacil’s Medieval epics Marketa Lazarova [1967] and Valley of the Bees [1968]), has the air of a folktale. Based on a 1943 novella by Dobroslav Chrobak, the story has a dreamlike tone. Dragon (Radovan Lukavský), a man with weathered features, a scar across his face and an eyepatch, walks back to the village he was driven from many years earlier. The inhabitants’ response is steeped in superstitious dread and intimations of some kind of witchcraft.

Dragon was a potter, an emotional and intellectual outsider whose creativity instilled distrust in his neighbours. Among those neighbours was Simon (Gustáv Valach) and his new bride Eva (Emília Vásáryová), who seems hypnotically drawn to Dragon. As the film shifts back and forth in time, we learn that Dragon was scapegoated during a devastating drought and driven from the village. On his return, Simon’s enmity remains strong, just as Eva’s attraction is reignited. But Dragon claims that he merely wants to be allowed to move back into his home and resume his pot-making.

When the villagers’ herd of cows is threatened by a forest fire, Dragon – who knows more of the world beyond the village – says that he can lead them away from the flames and save them. The village elders accept his offer and Simon goes with him, although the other man has ulterior motives. Simon’s distrust misreads Dragon’s actions and he heads back to the village to tell everyone that Dragon has betrayed them. In anger, the villagers burn Dragon’s home to the ground. When it turns out that he had acted in good faith and had indeed saved the herd, the villagers lose their distrust and are willing to accept him back into the community, but Dragon knows that he is destined to be an outsider here and the final image shows him in long shot walking away from the valley once more.

Although the narrative has the simplicity of a folktale (and echoes of the classic Western story of the outsider who serves a community which can never really absorb him into itself), Grecner’s technique is richly expressive, with a constantly moving camera which often seems to be swept up in the seething emotional currents of the characters; his use of a long lens, giving the images a very shallow depth of field, gives the film a pronounced two-dimensional quality with characters in close-up almost floating against an out-of-focus background in both cramped interiors and expansive landscapes.

There’s a primal quality to the film which evokes myths illuminating the origins of society and the forces of creation and destruction which define human interactions. And yet, Grecner made this, his third feature, at an inopportune time. Czechoslovakia in 1968 was overwhelmed by more immediate political concerns, rendering his expressive film irrelevant. It quickly disappeared, and he didn’t make another film for twenty-five years. Second Run’s PAL DVD has a stunningly detailed restored image, with deep blacks and rich contrast, and a hallucinatory sound track which uses layered voices, echoing distortion, and a powerful, unsettling score by Ilja Zeljenka which helps to create a soundscape analogous to the expressive camerawork.

The accompanying booklet has an informative essay by academic Jonathan Owen, but the filmed introduction by Peter Hames is disappointing; this expert on Czech and Slovak cinema offers little more than generalities padded with long excerpts from the film.

While I knew nothing of Grecner nor his film before Second Run’s release, Dragon’s Return nonetheless fits into a recognizable context, having emerged from the extremely fertile cinematic experimentation which flowered in Czechoslovakia in the mid-’60s. However, the third of my discoveries seems to fit nowhere except in its own decidedly idiosyncratic niche.

*

Catch My Soul (Patrick McGoohan, 1973)

Catch My Soul (1973) represents just why I love DVD and Blu-ray. Here is a film which I had never heard of before, although it was directed by an actor I admire, with whose work I had been familiar since the mid-’60s when I watched Danger Man as a child in England and later became obsessed with The Prisoner the year after emigrating to Canada. I have collected a number of oddities starring Patrick McGoohan over the years, particularly Arthur Dreifuss’ adaptation of Brendan Behan’s play The Quare Fellow (1962) and Michael Elliott’s striking BBC television production of Henrik Ibsen’s Brand (1959). There’s also Cy Endfield’s great working class noir Hell Drivers (1957) and Basil Dearden’s All Night Long (1962), an intriguing transposition of Othello to the contemporary jazz scene in London with McGoohan delivering an intense performance as Johnny Cousin, the Iago character.

This last is of particular interest with respect to McGoohan’s sole feature directorial credit. Catch My Soul, based on a stage production by Jack Good, is also a contemporary adaptation of Othello, in this case given a counter-culture rock opera treatment. While it sounds like a disaster waiting to happen, and in fact received pretty negative reviews on its very brief release in 1973, the result is a fascinating, emotionally resonant experiment which finds interesting ways to make Shakespeare’s tragedy relevant.

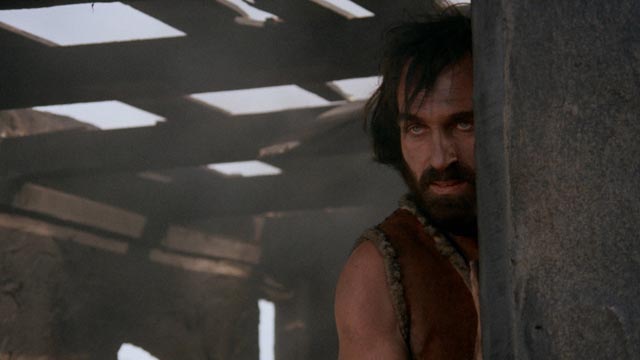

Here, Othello (Richie Havens) is a charismatic preacher leading a community of hippies and dropouts on the fringes of the New Mexico desert. We first encounter him during a powerful sequence of group baptism in a nearby river, around the fringes of which Iago (Lance LeGault) prowls, seething with resentment because the preacher has named Cassio (Tony Joe White) as his second-in-command. When Othello takes the chaste Desdemona (Season Hubley) as his bride, Iago sees an opportunity to get revenge for what he perceives as a personal betrayal.

The film follows the lines of Shakespeare’s original play, with both its strengths and weaknesses. In particular, Desdemona remains something of a pale cypher, while Iago’s anger and resentment seem out of proportion to the slight he has suffered. However, LeGault gives such a ferocious performance, becoming the embodiment of malevolent resentment, that he all but appropriates the role of protagonist; his actions eventually expose the innate weakness of Othello, which is an unacknowledged pride so deep that it blinds the preacher with a destructive self-righteousness.

While issues of race inevitably run through the film, as they do in the original play, the hypocrisy of religion is more central to the tragedy here (somewhat distorted and simplified by the alternate, distributor-imposed title on the print used for the disk’s transfer: Santa Fe Satan). The conflict between religion and human fallibility on display here is something which has been played out endlessly in ensuing decades as one prominent evangelist after another has been exposed for hypocrisy.

Catch My Soul had the misfortune to be released shortly after Norman Jewison’s Jesus Christ, Superstar, perhaps the only other film to which it bears any resemblance. But where Jewison’s film has the slick polish of a mainstream production, McGoohan’s has the ragged authentic feel of a counter-culture “happening” … something confirmed by the disk’s special features, which recount the chaotic story of the production. Shot by the great Conrad Hall, some of the bigger set-pieces, like the night-time party where Iago sets Cassio up for his fall, were captured more like a documentary record of an actual event, with the cast filled out by drunken partiers trucked in and turned loose to do whatever they felt like doing.

McGoohan, a heavy drinker, is also reported to have directed parts of the film while lying on his back on the ground because he was too drunk to stand up.

While the score may not be as loaded with catchy tunes as Superstar, the film features powerful vocal performances by Havens as Othello, LeGault as Iago and White as Cassio, with actress Susan Tyrrell giving strong support as Iago’s wife Emilia, her first role after being Oscar-nominated for Fat City (1972). Season Hubley is as good as she could be, given the insubstantial role of Desdemona, required to be little more than a symbol of wronged purity.

Apparently McGoohan had a falling out with Jack Good after completing his director’s cut; somewhere during production, Good went through a religious conversion and, in post-production, he shot additional material to insert more religious imagery (it’s unclear what parts were added by him as the film seems to have conceptual integrity). McGoohan disowned it and after its initial failure in a brief New York run, it was picked up by Cinerama Releasing, retitled Santa Fe Satan, and distributed on the drive-in circuit before vanishing for forty years.

The fact that it has now resurfaced, and in an impressive restoration from the original camera negative, given a dual-format release by Etiquette Pictures, the new boutique offshoot of exploitation specialists Vinegar Syndrome, seems remarkable. (Etiquette are also responsible for the release of James B. Harris’s Some Call It Loving [1972] and The American Dreamer [1971], a documentary portrait of Dennis Hopper by Lawrence Schiller and L.M. Kit Carson, made while Hopper was in the midst of the notorious production of The Last Movie.)

The disk’s image is excellent, with a pleasing, textured film look and the original mono sound seems to serve the music well. Extras include a retrospective making-of; an interview with Tony Joe White, whose first experience of acting this was; and a brief tribute to Conrad Hall and his cinematography by his daughter Naia. A trailer and promotional gallery are included, and the booklet has a lengthy and informative account of the production and its troubled history by Tom Mayer.

As long as companies like Etiquette go to all this effort to uncover and honour such obscure movies, the oft-prophesied death of DVD and Blu-ray will be held at bay, even if major distributors are giving up on the medium.

Comments