Recent viewing: April & May 2016

My friend Curtis and I recently went to see Ariel Vroman’s Criminal (2016). Although the story had potential, the movie turned out to be sluggishly paced and directed with little flair or imagination. Star Kevin Costner, who almost always underplays, and at times is weighed down by a kind of wooden stoicism, makes the central character strangely dull. The script by Douglas Cook and David Weisberg toys with a concept that goes way back to some of the lesser Universal horrors of the early ’40s, often written by Curt Siodmak, who virtually specialized in brain-transplant stories. His most famous creation is probably Donovan’s Brain (novel 1942, direct movie adaptations in 1944, 1953 and 1962; there have been many unofficial versions, including The Thing That Couldn’t Die, The Brain That Wouldn’t Die, They Saved Hitler’s Brain), but his most effective variation on this theme was the novel Hauser’s Memory (1968), which was turned into a pretty good made-for-TV movie by Boris Sagal in 1970.

In Criminal, as in Hauser’s Memory, a secret government group in desperate need of information contained in a now-dead man’s memory uses voodoo science to transplant a dead agent’s personality into another man’s head. In order for this to work, they need a kind of “clean slate” brain and the only one available belongs to a violent sociopath whose frontal cortex barely functions because of a childhood injury. This is Jericho Stewart (Costner). Needless to say, Jericho becomes internally conflicted as the personality of dead CIA agent Bill Pope (Ryan Reynolds) begins to impinge on him, gradually instilling human feelings and a conscience. The vicious killer at first resists the strange feelings of love and caring for the wife and daughter Pope left behind to mourn him, but eventually he turns into a good guy equipped with all the vicious animal skills of the killer.

All of this “character” stuff is embedded in a vaguely sketched narrative about a powerful businessman (Jordi Mollà) who wants to tear down the whole world and create chaos out of which some better society is supposed to rise (or something). The key to these schemes is a program called “the wormhole”, created by the Dutchman (Micheal Pitt), one of those magically talented movie-style hackers; it will give the businessman complete control of the U.S. nuclear arsenal so he can trigger World War 3.

There’s a lot of running around, a bunch of shooting, and a surprising amount of bone-headed incompetence on the part of the CIA, headed by Quaker Wells (Gary Oldman), who doesn’t seem to be capable of making the best use of the mind-transfer technique invented by a very gnomish Tommy Lee Jones. As Jericho struggles to deal with his confusion, Wells yells at him a lot while his men keep hitting Jericho in the head with the butts of their guns.

This all amounts to a tonally confused mix of violence and sentimentality that comes to a close with an apparent promise of a sequel.

*

Doomwatch (1970-72)

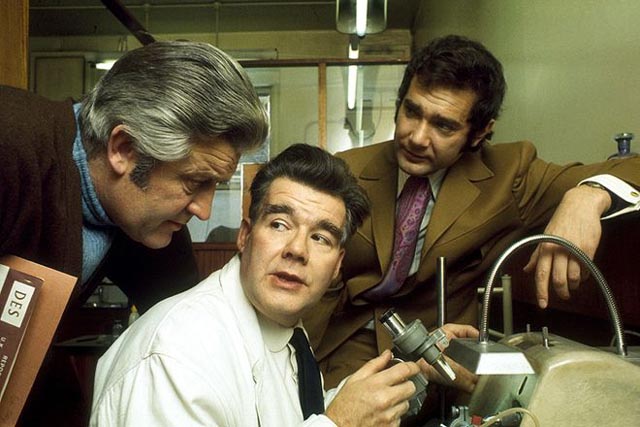

It took a few weeks to make my way through Simply Media’s 7-disk Region 2 set of all that remains of the BBC series Doomwatch (1970-72). This was one of those nostalgia trips, revisiting something I enjoyed back in the day because of its sci-fi trappings. Like so much of what the BBC produced from the ’50s through the ’70s, many of the show’s episodes were destroyed after their initial run; it was deemed financially rational, having spent the money to make a show, to erase the tapes and reuse them, rather than preserve them and buy fresh tapes for the next show. Even acknowledging that the tapes were an expensive material cost at the time, in retrospect the practice looks like nothing less than cultural vandalism. As a result, the episodes available in this new set (24 of the original 38) have been sourced wherever they could be found, most of them from technically weak dupes complete with dropouts and video glitches.

Created by Kit Pedler and Gerry Davis, who had both been involved with Doctor Who (Davis as story editor and Pedler as “scientific advisor”), Doomwatch dealt with a small government department tasked with monitoring the dangers of scientific research and industrial activity which posed social and ecological threats. Led by Dr. Spencer Quist (John Paul), whose dedication to the job is rooted in the part he had played in the development of the atom bomb, the department is constantly being attacked by vested interests and the minister who oversees it, because the group’s work interferes with the free exercise of the economic interests of both private industry and the state.

The stories involve problems like chemical pollution, the inadvertent release of dangerous biological agents, even the social and psychological dangers of a “rational” housing policy which stacks people into highly concentrated residential tower developments (a subject elaborated on by J.G. Ballard in his 1975 novel High-Rise, which has just been adapted to film by Ben Wheatley). Conceived as an adult series dealing with important issues, Doomwatch was hampered (as usual at the time) by very limited resources and the BBC’s somewhat primitive production techniques. Much of the show takes place in a few standing sets and consists of small groups of people engaged in lengthy conversations (or more often arguments) about moral and ethical issues. Quick shooting schedules mean that most episodes contain a few flubbed lines which the actors gamely push through to keep the scene going. To its credit, almost every episode ends without resolution, leaving viewers to ponder active threats facing society.

Sex and Violence, the final episode made for the third season, was never aired. It is an interesting attack on the reactionary moral crusading of the Nationwide Festival of Light and other such groups which eventually led to the video nasty scare of the ’80s and attempts by Margaret Thatcher’s government to enforce censorship through new criminal laws. In the episode, characters modeled on people like Mary Whitehouse turn out to be the pawns of a right-wing demagogue who is using a campaign against sex and violence in the arts, on television and in the movies to distract the public from economic issues and build a political base from which to launch a fascist movement. Splitting its running time between increasingly violent protests against pornography and lengthy scenes of a committee discussing permissiveness, repression and the need for sex education, the episode spells out one of the major strategies Thatcher would use to control and manipulate the British public a decade later as she set about destroying the postwar state in her quest to make the country safe for unfettered capitalist exploitation.

Despite its limitations, Doomwatch remains somewhat relevant because its overriding theme is that our survival requires not only an awareness of the consequences of our actions, but also a willingness to pay for what needs to be done to alleviate the impact we have on the environment. That argument is central to the “debate” about climate change today, with most of the deniers resisting the evidence because it would simply cost too much to make the changes necessary to slow down the damage we’ve been inflicting on the planet. The show is often clumsy and given to preachiness, but it does nail the unfortunate human tendency to place economic interests ahead of everything else, even our own survival as a species.

The set includes a half-hour retrospective documentary which sketches in the series’ background and considers its impact on issues at the time; apparently there was some pressure from the government to abandon at least one proposed episode (about the dangers of lead in gasoline), which the BBC was independent enough to make anyway.

*

La Piscine (Jacques Deray, 1969)

Although Jacques Deray had a career which spanned four decades, specializing mostly in crime films, he seems never to have gained the kind of profile outside France which someone like Jean-Pierre Melville achieved while working in similar genre territory. And yet Deray worked with many major actors – Charles Vanel, Claude Dauphin, Lino Ventura, Jean-Paul Belmondo, Jean-Louis Trintingnant and Alain Delon – some of them multiple times. While his gangster films, like Borsalino and its sequel, are fine genre works, perhaps his most notable film is La Piscine (1969), a tense and unsettling psychological thriller suffused with sexual tension and potential violence.

A pair of lovers, writer Jean-Paul (Alain Delon) and journalist Marianne (Romy Schneider), are enjoying a languid vacation in a villa on the Riviera when her former lover, record-producer Harry (Maurice Ronet) drops by with his nubile teenage daughter Penelope (Jane Birkin). Emotions begin to simmer as the quartet spend a lot of their time barely dressed around the villa’s swimming pool. Jean-Paul, suffering from writer’s block, seems to be plagued by feelings of impotence as Marianne and Harry appear to be reigniting their former relationship; in part to counter this, and perhaps in part to overcome those feelings of inadequacy, Jean-Paul is drawn towards the sexually active girl.

Co-written by Deray and Jean-Claude Carriere, the film presents an enticing, shimmering surface of attractive people basking in their privilege, while underneath dark eddies of fear, resentment, insecurity and stifled desire slowly but inevitably come to a boil. The languid pace evokes the pleasures of that privilege while allowing the darkness to grow at a subtle pace, gradually sneaking up on the viewer.

The Region 2 DVD from Park Circus does full justice to Jean-Jacques Tarbes’ luminous cinematography.

*

52 Pick-Up (John Frankenheimer, 1986)

It could be said that by the ’80s, John Frankenheimer’s best days were behind him, although he did continue occasionally to make something worthwhile and, truth be told, even his great films of the ’60s and ’70s had been mixed in with notable duds (The Extraordinary Seaman, The Horsemen, 99 and 44/100% Dead, Prophecy). Although there are echoes of the political concerns of his great films in some of that later work, most of his thrillers through the ’80s and ’90s seem routine, formulaic, and instead of the innovative artist of The Manchurian Candidate and Seconds, in the last two decades of his career Frankenheimer was mostly a journeyman for hire. His technical skills may have been intact, but for the most part you don’t sense a great deal of commitment to the material he was working with. I wouldn’t want to read too much into some of these films, but it’s tempting to think that disillusionment had soured the once-progressive filmmaker who remained haunted by having driven his friend Bobby Kennedy to the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles on the day the candidate was assassinated.

There’s an air of tired cynicism in some of the later thrillers. In a few, this attitude bends towards a sadistic unpleasantness. This is nowhere more apparent than in 52 Pick-Up, Frankenheimer’s adaptation of an Elmore Leonard novel (co-scripted by the author). There’s none of the breezy lightness or comic tone of Get Shorty or Out of Sight here. It’s a grim story about Harry Mitchell (Roy Scheider), a successful businessman married to Barbara (Ann-Margret), a politically active woman. Harry has had a brief affair with Cini (Kelly Preston), a much younger woman he met in a bar, who turns out to be involved with some sleazy guys who used her as bait to trap him. Armed with recordings of the affair, the gang set out to blackmail Harry; and he in turn sets out to play them off against each other.

Harry manages to track each of the blackmailers down, convinces the leader Alan Raimy (John Glover) that he doesn’t have all the cash they’re asking for, and gets each of them to believe that the others are planning to betray them. Harry isn’t a crude vigilante like Death Wish’s Paul Kersey; he uses his brains and business skills to outwit the thugs (although by the end his skills have become pretty implausible). All of this is skillfully orchestrated by Frankenheimer, who keeps his camera moving all the time to instill events with some dynamic energy, but you realize at the end that the core of the drama – the damage inflicted on a long marriage by Harry’s brief lapse (possibly triggered by Barbara’s escalating involvement in politics) – has pretty much been swept aside by the mechanics of the plot, and the film winds up without any real point. That vacuity, combined with some pretty nasty moments of violence, leaves a sour taste.

*

Fear & The Machine That Kills Bad People

(Roberto Rossellini, 1954/1952)

Roberto Rosellini, although one of the key figures of Italian neo-realism, having virtually invented the movement with Rome, Open City (1945) and Paisan (1946), was already pushing against the constraints of the form by the late ’40s. Last year, the BFI released a Rossellini double-bill on DVD which represents two different directions his work took as he searched for a way out of neo-realism.

Fear (1954) was the fourth of the five features Rossellini made with Ingrid Bergman and although it bears some similarities to the three films which preceded it, it is nonetheless quite different in style and tone. Once again Bergman plays a woman faced with marital problems, in this instance the almost overwhelming stress arising from her affair with another man while remaining deeply involved with the family business she shares with her older husband, Albert (Mathias Wieman). When a woman claiming to be her lover’s former girlfriend shows up demanding money, Irene (Bergman) struggles to conceal the affair from Albert while trying to scrape together the money to pay off the blackmailer.

Fear is suffused with a noirish atmosphere and uses a very Hitchcockian approach to its examination of guilt, generating increasing levels of suspense and desperation. A revelation about two-thirds of the way through shifts the emphasis from suspense to something more akin to a morality play, leading towards a transition from guilt to redemption. This final act, however, seems rather perfunctory and far less successful than the melodrama which has preceded it. Rossellini’s play with Hollywood style isn’t entirely successful, making Fear perhaps the least of his collaborations with Bergman despite her fine performance, and yet much of the film is very effective and as a deliberate experiment in form and style it helps to illuminate the choices the director would make as he moved towards the historical films which occupied him throughout the ’60s and ’70s.

Although released just two years before Fear, the supplementary feature on the disk was originally shot in 1948 and represents an even more transitional experiment. There are obvious traces of neo-realism in The Machine That Kills Bad People (1952) in the use of locations and non-professional actors, but in content it shifts towards metaphor and fantasy (like Vittorio De Sica’s Miracle In Milan [1951]). A strict adherence to realism was proving limiting to an artist who wanted to explore more than the material conditions of life in post-war Italy.

In a small seaside town poised to become a tourist destination with development funded by former U.S. soldiers who have returned to Italy a few years after helping to liberate the country, a figure who may be the town’s patron saint, or may be a mischievous demon, grants a local photographer the power of life and death. This man, Celestino Esposito (Gennaro Pisano), discovers inadvertently that when he uses his camera to duplicate an existing photograph the subject of that picture dies. He tries to convey this information to the mayor, but the mayor and the rest of the local ruling class are so preoccupied with the impending development and the personal profit they’re likely to make that Celestino is brushed aside.

The depiction of greed and corruption has a neo-realist edge, but Celestino and his camera add a note of comic fantasy as he tries to use its power to influence events supposedly for the better. Inevitably, the consequences of his actions don’t turn out the way he hopes. As he sets out to remove the wealthy parasites who rule the town, the poor become just as greedy and self-serving as they rise in status. It gradually becomes apparent that if he’s to pursue his mission, Celestino must inevitably kill everyone because no one is free of human weaknesses. The assignment of punishment to sinners begins to appear arbitrary. Even the best of intentions just make the situation worse.

The Machine That Kills Bad People is rough around the edges, reflecting the circumstances of its production – Rossellini apparently wasn’t terribly engaged by the project and left much of it to his assistants – but it remains quite engaging, with some effective comic touches. As an amusing allegory about corruption in post-war Italian society and a satire on crass Americans trying to take over the country, it seems anomalous in Rossellini’s career and even more than Fear represents a path not taken by the filmmaker.

Comments