The pleasures of transgression

Roughly speaking, the chief difference between experimental film and underground film is a matter of technique in the first and content in the second. Of course, there are countless possibilities for combining the two, but experimental film is most often concerned with exploring the ways in which film as a medium can be manipulated, using the qualities of light and colour, the juxtaposition of visual and aural elements. At its purist, experimental film comes closer to visual rather than dramatic or narrative art.

Underground film, although it may explore the plastic qualities of the medium, tends towards the use – and frequently the subversion – of film’s narrative qualities, offering to show an audience what is generally forbidden by the mainstream. But more than the subversion of narrative form, underground film attacks social norms in ways which the commercial industry is usually too timid to attempt. Hence the polymorphously perverse assaults on good taste perpetrated by John Waters and his star Divine.

During the ‘60s and ‘70s, as the long-standing controls of industry censorship were weakened by the decline of the studios, the mainstream flirted with underground sensibilities. The Oscar-winning Midnight Cowboy (1969), for instance, brought to commercial screens the kind of gender and sexuality issues Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey had been exploring in their work. Based on James Leo Herlihy’s novel about a naive small town boy who arrives in New York City and ends up a hustler, John Schlesinger’s film combines an extremely grimy image of the big city with some flashy camera and editing techniques which occasionally get in the way of the deep emotional resonance established between Jon Voight and Dustin Hoffman; but perhaps those techniques were deemed necessary to make palatable to a mainstream audience what was essentially a potent love story between two damaged men.

Just the year before, with more traditional polish but less conceptual and dramatic success, a French actor directed an adaptation of an openly pornographic satirical novel which featured a surprisingly high profile cast.

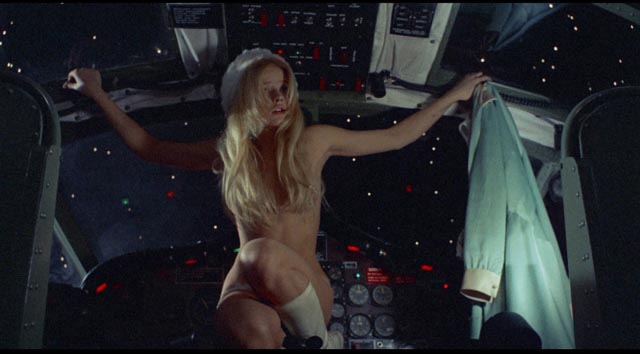

Candy (Christian Marquand, 1969)

The novel Candy, written by Terry Southern and Mason Hoffenberg in the late ‘50s, is a loose modern variation on Candide, describing the adventures of a naive high school girl named Candy Christian (Ewa Aulin, pretty but vacuous) who inadvertently provokes lust in every man she meets, while paradoxically retaining her own wide-eyed innocence. As adapted by Buck Henry, the story retains its episodic nature built around satirical depictions of various institutions – education, medicine, religion and so on – all of which are reduced to absurdity by their male representatives’ inability not to be reduced to rutting animals by Candy’s presence.

The cast is impressive: Richard Burton as the pretentious poet MacPhisto, Marlon Brando as the guru Grindl, James Coburn and John Huston as doctors, Walter Matthau as a demented general, John Astin in a dual role as Candy’s father and uncle, Charles Aznavour as a hunchback, Ringo Starr rather embarrassingly as a Mexican gardener, with Elsa Martinelli, Anita Pallenberg and Sugar Ray Robinson in minor roles. This cast gives the film something of the chaotic, shapeless feel of multi-star extravaganzas like Casino Royale (1967), but the photography of Giuseppe Rotunno gives it an impressive visual sheen which is continuously at odds with the supposedly transgressive content.

The main problem with the film, despite some effective sequences, is its reluctance to give in to the novel’s essentially pornographic purposes. Although the central theme is the ways in which all these patriarchal authorities use and abuse the innocent Candy, it remains stubbornly coy about the sex, falling back continuously on what are largely unfunny comedic elements. The film is visually quite elegant, but completely unerotic. In fact, that elegance is part of the problem; it needs to be grimier and more offensive for the satire to work at all.

The Kino Blu-ray looks gorgeous and features an engaging interview with scriptwriter Buck Henry, who is quite open about his intentions and the failure of Marquand to breathe much life into the material. A brief interview with critic Kim Morgan is less convincing in its attempt to establish Candy as a “timeless” classic.

*

Thundercrack! (Curt McDowell, 1975)

The charge of being insufficiently grimy and offensive certainly can’t be laid against Curt McDowell’s Thundercrack! Made on virtually no budget yet on an almost epic scale, scripted by George Kuchar and shot by McDowell himself in atmospheric black-and-white, this 160-minute movie grafts unapologetically pornographic activity onto a lively pastiche of old-dark-house horror movies. On a stormy night, various travelers find themselves in the remote, labyrinthine house of widow Gert Hammond (Marion Eaton, an actress who ended her career with small roles in three of Dan Ireland’s features). This disparate group proceed to spend the night engaging in various sexual combinations, hetero-, homo-, lesbian – and finally bestial, as Bing (writer Kuchar) gives in to his passionate feelings for a gorilla.

Interestingly, Kuchar wrote the script to express his feelings about just how awful it is to be enslaved to sexual desire, while McDowell directed the film as an expression of polymorphous sexuality as a kind of liberation. Despite the film’s length, it never feels long and surprisingly the graphic sex doesn’t have the emotional numbness of so much blatant pornography, but rather has a tone of affectionate sweetness.

Synapse Films’ 40th Anniversary Collector’s Edition comes not only with an impressive transfer made from the one existing uncut 16mm print, but is loaded with a rich selection of special features which not only situate it in the context of its underground moment but also conveys an engaging portrait of McDowell as a pioneering gay filmmaker. (Apparently only five prints were ever made, with three of them being chopped up by the producers and others, while the fifth was seized by Canadian customs.)

On the main disk, there’s an 85-minute conversation (audio only) with McDowell recorded in 1972, before the production of Thundercrack!, while he was still at film school. He comes across as very self-aware about both his intentions and his limitations as a filmmaker, particularly as they relate to an exploration of his own sexuality through film.

The Blu-ray also contains the full-length documentary It Came From Kuchar (1:26:25, 2009) directed by Jennifer M. Kroot. This covers the underground film careers of the Kuchar twins, George and Mike, their own productions and collaborations with others, as well George’s work as a film teacher. Packed with admiring interviews with a wide range filmmakers who cover the spectrum from outrageous to mainstream, the documentary places the brothers at the centre of a transgressive movement which ransacked established genres and commercial tropes for subversive and satirical purposes.

There is also a second disk, on DVD, which contains five of McDowell’s short films, again combining sex with provocative humour – one is even a colour musical. There’s a brief piece with star Marion Eaton recalling the experience of working on the film; she also appears with McDowell on a cable access talk show from 1976, with the pair promoting Thundercrack! McDowell is as engaging here as in the audio interview, displaying a very clear sense of the difference between what he was doing and more “mainstream” pornography; Eaton is unselfconscious about the demands of playing explicitly erotic scenes.

There’s also an interview with composer/sound effects editor Mark Ellinger about his creative role in the production; some behind-the-scenes footage and outtakes from the sex scenes; and an extensive selection of audition footage in which each performer is asked to strip for the camera, some being obviously uncomfortable, while others take it in stride.

Considering that before this release I had never even heard of McDowell and his underground epic, this Synapse release has provided a crash course in yet another obscure facet of movie history. While I admit to feeling a bit self-consciously disreputable for owning up to watching Thundercrack!, I’m also pleased to have it in my collection. This is what I appreciate about genuine underground films: being made aware of areas of experience not generally accessible in day-to-day life, but with a kind of pleasurable frisson at violating boundaries that comes with that exposure.

Kuchar Footnote

After watching Thundercrack! and the accompanying documentary about the Kuchar twins, I went looking for some of their other work. The out-of-print DVD of Sins of the Fleshapoids proved prohibitively expensive from various on-line sellers, but I did come across a previously unheard of title which was reasonably priced, so I took a chance.

Rufus Butler Seder’s Screamplay (1985) pretty much defines the term “independent”, though its good-natured play with familiar genre tropes perhaps disqualifies it from being “underground”. Rather, it’s a lovingly hand-crafted homage/parody of Hollywood B-grade “murder movies”. The closest thing I can think of that it resembles is John Paizs’ Crime Wave, also made in 1985 and also centred on a struggling screenwriter whose attempts to complete a crime movie script unwittingly draw him into a series of real crimes.

While both films’ have various structural problems, their affectionately crafted old-school effects – matte-paintings, in camera compositing, and so on – display a genuine love of film’s visual possibilities. In Seder’s film, this involves some wonderful image-making using a combination of home-made front projection (the system was built by Seder’s father), which at times produces an almost Lynchian sense of unreality, and very effective in-camera compositing which allows Seder to expand his threadbare sets in witty ways. The multilevel apartment courtyard was created by running the black-and-white reversal film through the camera multiple times, adding the balcony levels progressively with each pass.

As in Thundercrack!, while the performances may not seem like traditional “good acting”, they have an interesting naturalness which is entirely in keeping with the film’s overall tone – again, somewhat similar to the stylized performances which fit so perfectly into David Lynch’s imaginative world. Seder himself plays protagonist Edgar Allen, who arrives in Hollywood with little more than his typewriter, takes up residence in the Welcome Apartments as a part-time handyman, and finds that “real life” begins to echo scenes from his serial killer script (or is the script provoking events in reality?). Seder’s performance emulates a certain kind of wide-eyed silent-film exaggeration, while others in the cast play it straighter, more like the inhabitants of an old noir B-movie – these include ageing starlet Nina Ray (M. Lynda Robinson), ingenue Holly (Katy Bolger), police sergeant Joe Blatz (George Cordeiro), hustling failed agent Al Weiner (Seder’s father Eugene), and (the reason for bringing this up at all) George Kuchar as the somewhat obnoxious, frustrated romantic caretaker Martin.

Seder’s enthusiasm as director and star render the weaknesses of the script he co-wrote with Ed Greenberg relatively unimportant. Screamplay succeeds very well in establishing its own little world, packed with visual, and at times verbal, wit. In fact, despite having no idea what I would be in for (and with expectations somewhat lowered because the DVD was released by Troma, a company whose output is generally amateurish, incompetent and unwatchable), I was pleasantly surprised to find it one of the most entertaining movies I’ve seen in some time.

The disk contains the usual Troma extras which allow Lloyd Kaufman to mug and boast, and an extraneous brief interview with old Hollywood hand Vincent Sherman (whose 1941 anti-Nazi movie Underground was strangely also released on disk by Troma). But the most pertinent extra is a commentary by Seder, in which he alternates between interesting observations about the techniques he used to create the film and honest evaluations of its shortcomings, at least by conventional industry standards. This track is a bit spotty, with long silences, and would have benefited from a moderator who could have prodded the director to elaborate on some of the more interesting points he just skims over.

The transfer itself looks surprisingly good for something shot on 16mm reversal stock.

Comments