Criterion Blu-ray review: Herk Harvey’s Carnival of Souls (1962)

One of the pleasures of what has been called “regional filmmaking”, that is movies made far from the centre of the mainstream, is that it occasionally gives rise to strange and unexpected movies, movies which don’t adhere to tried and true commercial formulas, even when they have obviously been made in the hope of generating financial returns. While filmmakers working on the fringes do create dramas which reflect a reality often ignored or glossed over by the industry – say, Eagle Pennell’s The Whole Shootin’ Match (1978) or Kent Mackenzie’s The Exiles (1961) – these filmmakers often take familiar genres as a starting point, using them as a kind of commercial hook. But then, without the constraints imposed by studio executives’ commercial concerns, they sometimes achieve an originality which renders technical and budgetary limitations irrelevant.

Needless to say, horror has been one of the more frequently used genres, ranging from the “realism” of Charles B. Pierce’s atmospheric true-life serial killer movie The Town That Dreaded Sundown (1976) to the fairytale tone of Richard Blackburn’s Lemora: A Child’s Tale of the Supernatural (1973) and Curtis Harrington’s Night Tide (1961). One of the most successful (commercially and creatively) is George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968), a movie which radically changed the face of the horror genre by giving its fantasy elements a solid grounding in a sense of documentary realism.

Romero has acknowledged that one influence on his debut feature was a small black-and-white film made in Lawrence, Kansas, six years earlier, but Herk Harvey’s Carnival of Souls (1962) is closer in tone to Harrington’s Night Tide. Both seem more influenced by European cinema than Hollywood – Harvey himself cited both Bergman and Cocteau as his own influences, a heady pair for someone making his first (and only) feature for about $30,000 in the heart of the Midwest. However, although their stylistic choices were very different, Harvey had much in common with Romero as a filmmaker.

Both were well-established directors of commercials and industrial films (Romero at The Latent Image in Pittsburgh, Harvey at Centron in Lawrence), a point which bore on their creative choices. Their movies have an economy of technique which can be seen as rooted in the functional needs of purely informational filmmaking. But they also differ: Romero uses a raw, at times radical editing style to create a deep sense of instability and a relentless atmosphere of pervading fear, while Harvey achieves something more poetic and allusive. Romero’s film observes its characters with a chilly documentary eye, while Harvey’s is imbued with a deep subjectivity, its unsettling tone deriving from our almost claustrophobic alignment with the perceptions of his heroine, who from the film’s beginning seems to have been wrenched from any firm connection with the world.

That beginning, in which we are introduced to Mary Henry (Candace Hilligos) as one of three young women in a car stopped at a red light, could have been lifted directly from the kind of high school driver education movie produced by companies like Centron. Another car pulls up beside them and the cocky male driver challenges them to a race. As in those driver ed movies, this leads to tragedy: on a narrow bridge, the driver of the car carrying Mary loses control and it plunges through a railing and disappears into the river below.

After hours of searching without any luck, the police and the crowd of locals who have gathered by the river are surprised to see Mary emerge from the water onto a mud bank. She has no memory of what happened in the time between the crash and her reappearance, but apart from being in shock seems unharmed.

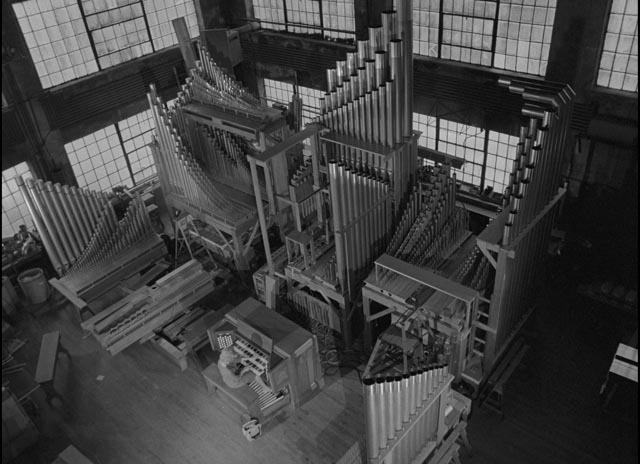

Mary, a trained organist, has recently been hired to play for a large church in Salt Lake City and she can’t wait to get away from Lawrence and the site of the mysterious crash. In a scene set in the visually impressive organ-making factory, we first learn something important about the young woman; while technically an expert on the great instrument, she has no religious beliefs, no sense of spiritual calling for the work she is going to do. Here we get the first hints of the disconnection which will steadily increase over the course of the film.

On her way to Salt Lake City, the road takes her past the strange sight of a gigantic pavilion located out on the salt flats. This is Saltair, a huge spa and amusement park originally built in the 1800s before the lake receded and left it stranded on land. (It is also the original inspiration for Carnival of Souls, having been seen by Harvey a few years earlier, prompting him to ask a colleague at Centron, John Clifford, to come up with a script which could use the location.) The pavilion exerts a strange pull on Mary and, as she drives by, we get our first glimpse of a haunting, ghost-like figure which inhabits it. This figure (played by Herk Harvey himself) suddenly begins appearing to Mary as she drives, most startlingly peering in through the passenger side window as if floating just outside the car as she speeds down the highway.

Once she reaches the city, Mary tries to settle into her new life, meeting her boss, the church’s minister (Art Ellison), and Mrs. Thomas (Frances Feist), her chatty landlady at a rooming house where there is only one other guest. This is John Linden (Sidney Berger), the creepiest neighbour you can imagine, who immediately begins hitting on Mary in a comically blatant way.

As Mary fends Linden off and impresses her boss with her playing, she keeps getting glimpses of the ghostly man from the pavilion. She also becomes aware of her own crumbling attachment to reality when she visits a department store and a strange spell overtakes her in the change room (an apt setting). The image ripples in a watery way and all sound falls away. When she emerges, all the people on the shop floor completely ignore her, neither seeing nor hearing her. In panic, she runs out into the street where just as abruptly the sounds of the world flood back in. Near hysteria, she is taken in hand by a passing doctor who brings her to his office and hears the story of her accident and the mysterious fugue state she has just emerged from.

In her desperation to feel attached to the world which now seems so tenuous, Mary accepts Linden’s invitation to go out with him. But this attempt to reconnect is awkward because she’s completely oblivious of the blatant sexual tone of his come-on and as he finally gets her alone in her room, he appears to her as the ghostly man and in her panic she scares him off.

Unable to resist the pull of the pavilion any longer, Mary drives out there and explores the vast building and its grounds. There are small subtle hints of otherworldly forces, leading eventually to the film’s big set piece, a great ball populated by the dead who, having spotted Mary, suddenly pursue her out onto the salt flats.

The film’s ending is well enough known that it need not be mentioned here. To some degree, it now seems obvious, but that’s largely because the device used by Harvey and Clifford has been used many times since. And yet, the film remains ambiguous even after many viewings – questions of what is real and what is subjective illusion are stubbornly unresolved – and this is what gives Carnival of Souls its lasting power. It refuses to be dismissed with a simple “oh, that’s what was happening”.

In the partial commentary track on Criterion’s superb new Blu-ray, carried over from earlier editions of the film, Clifford refuses to offer any pat explanations and asserts that in building the script around a few basic characters and available locations (particularly Saltair and the organ factory), he was largely inventing as he went along and didn’t know where it would end up when he created that mysterious opening with Mary inexplicably emerging from the river. Does the film take place in purgatory, or is the traumatized Mary engaged in real events in a world to which she is now only tenuously attached? Although she is haunted by the ghostly man, he actually does nothing to threaten her; is he warning her of something or simply trying to make her understand her situation, to accept what has happened to her and let go?

All this uncertainty is actually aided by what might superficially be considered the film’s technical and creative shortcomings. (These shortcomings have caused some commenters to refer to the film as overrated and even inept, a judgement rooted in a narrow definition of what constitutes “good filmmaking”; Harvey himself in the commentary refers to certain elements of the film as “amateurish”.) Given the very restricted budget, much of the location dialogue was looped in post-production, with faulty lip-sync and inappropriate ambiances; Foley is obvious, particularly in the sound of Mary’s footsteps in scenes where she enters her fugue state. But while these things can be considered technical faults, they also serve to emphasize the unnaturalness of the world Mary finds herself in and amplify her sense of disconnection. A case of technical limitations (perhaps inadvertently) becoming valuable creative elements.

This is true of the performances as well. Candace Hilligos was the only professional actor in the film, having trained with Lee Strasberg in New York. Sidney Berger did have theatre training, and eventually went on to found the Houston Shakespeare Festival, but the rest of the cast was drawn from local talent in Lawrence. A number of characters have the somewhat stilted feel of the types found in the industrial films Harvey was making for Centron (several of which are included on the disk), adding to the strange tone of many scenes as Hilligos’ intensity bumps up against figures which seem slightly unreal. This is most pronounced in the several lengthy scenes with Berger, whose John Linden is one of the most blatantly creepy characters you can imagine, all but drooling over Mary in his urgent desperation to get her into bed. The fact that Mary at times responds to him positively – particularly when he knocks on her door early in the morning, offering her some freshly brewed coffee (and a hit of whisky) – can be seen in a couple of different ways. Someone out of sympathy with the movie might see it as incomprehensible and tonally false; given how unappealing the character is, why does she encourage Linden?

But if one views the film as a depiction of a woman struggling to comprehend her own radical sense of dislocation, her intermittent attempts to engage with Linden become more understandable, although as an individual he has nothing to recommend him. She is clinging to him as a lifeline, a means to reassert a sense of normality against the increasingly disconcerting events she finds herself caught up in.

This drifting in a dreamy state of unreality permits a fairly straightforward reading of the film as an atypical ghost story (vaguely reminiscent of Alejandro Amenabar’s The Others [2001]), a reading in line with Harvey’s and Clifford’s original intentions to make a low-budget horror film to take advantage of the resources and locations available to them.

But whether intentional or not, there are other possible readings of Carnival of Souls, in particular as a kind of proto-feminist parable. Mary asserts at several points that she is strong-willed and independent, unwilling to bend herself to the various definitions proposed by the male authorities she encounters. But before this begins, before the strangeness overtakes her life, we get that opening sequence of the drag race in which a couple of guys challenge the girls and eventually run them off the bridge into the river. After the crash, those guys conceal their own responsibility by telling the police that the girls were driving dangerously, that they crashed while trying to force their way past on the narrow bridge. The men instigated the race, yet deny all responsibility for the deadly consequences, putting the blame entirely on the women.

Having risen from the river, Mary sets off on her journey with a complete denial of religion’s authority over her (raising doubts about her character in the minds of the men at the organ factory). Her new boss in Salt Lake City admires the beauty of her playing, but is shocked when she asks him to take her into the fenced off Saltair pavilion, because that would be a violation of the law. Her apparent disinterest in following such rules makes him look at her strangely, raising doubts which peak when he finds her playing profane music in his church (in a sequence which cements her uncanny connection with the pavilion and its ghostly inhabitants, one of several instances in which Harvey uses allusive editing to bridge time and distance in a poetically suggestive way). Here, the minister’s complete lack of compassion and understanding are striking. He fires Mary on the spot for lacking any spiritual calling, rather than responding to her as someone experiencing the aftereffects of serious trauma.

The doctor who takes her to his office after her first episode of disassociation is equally insensitive; he berates her for her hysteria and, having listened to her story, offers nothing but bromides drawn from conventional medical attitudes towards women’s supposedly innate emotional weakness. The limitations of these male authorities are highlighted by the crudity of Linden, who reduces that male authority to its basest terms in his whining complaints that she won’t just give him what he wants from her; in the purgatory Mary finds herself trapped in, she is fighting against the efforts of these men to confine her within a definition which denies her autonomy and demands her submission to their rules and desires. The film bleakly leaves her with nowhere to assert herself, with an acceptance of death her only way out.

Despite the originality of the film and its many strikingly effective moments, Harvey never made another feature. This appears largely due to the fact that it was very poorly distributed and he and his collaborators never saw any money from it. Which is not to say that he had no filmmaking career. Both before and after Carnival of Souls, he made hundreds of films for Centron over a period of decades. Still, it’s a pity he didn’t make any other dramatic features as there are many moments of great beauty and mystery in this strange film.

The disk

Criterion’s Blu-ray uses a new 4K transfer from the original camera negative and the film has never looked better; the high resolution reveals the richness and detail of Maurice Prather’s photography. The rich blacks give the many night scenes much greater impact than they ever had in earlier video presentations.

The mono sound, taken from the original 35mm sound negative, has depth despite the technical issues around looped dialogue and Foley effects. Harvey’s creative use of distortion and silences, combined with Gene Moore’s organ score, supports the otherworldly atmosphere evoked by the imagery and editing.

The supplements

Criterion have loaded the disk with a wealth of supplements (three-and-a-half hours’ worth), most of which are carried over from their 2-disk DVD edition from 2000, starting with the partial commentary track featuring a joint interview from 1989 with Harvey and Clifford, who both provide interesting background details about the origins of the production and its subsequent fate. They even broach questions about the film’s meaning, with Harvey offering some thoughts while Clifford declines to be specific.

Also carried over are an extensive collection of outtakes accompanied by Moore’s score (27:09); a documentary about a cast and crew reunion also from 1989, made to mark the film’s re-release (32:12); a collection of six shorts made for Centron between 1954 and 1982 (totaling 59:03), introduced with an essay about the company written by Ken Smith and read by Dana Gould (9:56, available on the old DVD edition only as a text extra); and a trailer (2:17). Strangely missing is a brief TV piece looking at what subsequently became of the film’s locations, included on the old DVD and listed on the Blu-ray’s cover, but not actually included on the disk.

New to the Blu-ray are a kind of introduction by comedian Dana Gould (22:41), talking about his affection for horror films in general and this one in particular. To tell the truth, I was left unsure about why he was here as he doesn’t have anything particularly enlightening to say. Much more informative is a video essay by film critic David Cairns (23:36) which delves into the film’s imagery and its mysterious atmosphere.

While the old DVD has a text history of the Saltair pavilion, the Blu-ray includes a 1966 TV program about it (26:00), which unfortunately is technically very rough; the video image is murky and the sound at times difficult to make out clearly.

Finally, there are three brief deleted scenes (totaling 4:01), all of which add little to the film, but which nonetheless point to the biggest difference between the Blu-ray and the original DVD edition. That earlier release also included what was termed the director’s extended cut into which Harvey reinserted some five minutes of material trimmed from the original 1962 release. That version now exists only in standard definition video and Criterion have chosen not to include the additional scenes even in a branched alternate cut on the disk because of the noticeable shifts in quality. Because the additions are not really significant to the film dramatically or stylistically, this is a minor point, but fans may want to hold onto their copy of the DVD edition even while enthusiastically upgrading to the Blu-ray for the greatly improved visual presentation.

Comments

I want to see Carnival of Souls.

I stopped reading your review because you give far too much info. for me before viewing.

I wonder why movie trailers or previews often give away so much plot, etc.

What do you think?

Well, Grant, in the case of a 54-year-old movie I think it’s perfectly legitimate to discuss it in some depth. How should one analyze a movie, a book, a play if it’s not permitted to talk about the content? Would it be unacceptable to mention that Hamlet dies in the end? Personally I think the modern obsession with “spoilers” is rooted in a fundamental misunderstanding of the experience of reading/viewing and how we respond to the narrative experience. At least my understanding of it! I think there’s more to it than simply needing to be surprised. Why else do we return again and again to our old favourites? It certainly has nothing to do with not knowing what’s going to happen.

But that said, I hate most modern movie trailers because they try to tell the entire story in three minutes …