Criterion Blu-ray review:Luis Garcia Berlanga’s The Executioner (1963)

Although I saw and was impressed by Victor Erice’s The Spirit of the Beehive in the early ’70s, my impressions of Spain and cinema have long been dominated by the foreign productions which so often used the country as a location during the Fascist regime of General Franco. These ranged from the series of epics produced by Samuel Bronston in the ’60s to David Lean’s Dr. Zhivago to the numerous spaghetti westerns which made use of the country’s desert vistas. Orson Welles had a long relationship with the country (an interesting point given his leftist leanings), partially filming Mr. Arkadin there in the mid-’50s, and wholly filming Chimes At Midnight and The Immortal Story there in the mid-’60s. But none of these films had anything to say about the country itself.

Spanish cinema, after some success in the ’30s in the atmosphere inspired by the Republic, had been severely constrained in the years after Franco’s Fascists seized control in 1939. Unlike the Communists in Russia and the Fascists in Italy and Germany, the Spanish dictatorship, allied with the Catholic Church, distrusted the popular power of movies and enforced strict censorship which only began to loosen somewhat during the ’60s – perhaps under the economic influence of all that foreign production.

Typically artists living and working under repressive regimes seek coded ways in which to comment on and critique the system, using symbolism and metaphor to slip potentially dangerous ideas past the censors. (Censors are often the most literal-minded of people, concerned with overt ideas and imagery.) One approach might be to shape a narrative within certain genre conventions, familiar tropes deflecting attention from underlying ideas. In Juan Antonio Bardem’s Death of a Cyclist (1955), the filmmaker embeds a sharp critique of the class divisions in Franco’s Spain within a melodrama about a bourgeois couple destroyed by guilt after accidentally killing a cyclist in a late night hit-and-run. By keeping his focus closely on the personal narrative of the couple, Bardem disguises his deeper themes within what superficially appears to be a traditional morality tale.

Luis Garcia Berlanga takes a similar approach in The Executioner (1963), newly restored and released on disk by the Criterion Collection. Here, rather than melodrama, Berlanga uses the forms of domestic comedy to create a devastating portrait of the emotional and moral costs of living under the Franco regime.

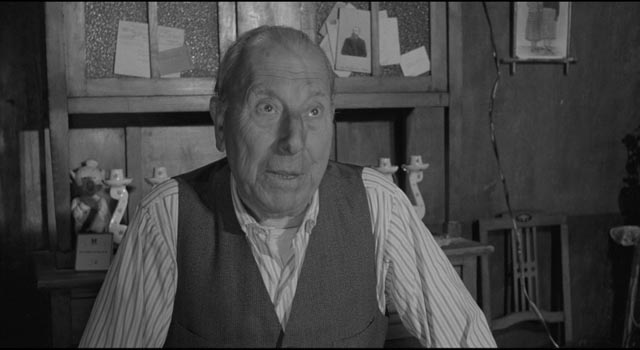

Jose Luis (Nino Manfredi) is a likeable but rather ineffectual guy. He meets more or less by chance Carmen (Emma Penella), a woman who by local standards is already getting beyond marriageable age. They begin a relationship, and eventually she becomes pregnant, much to the horror of Amadeo (Jose Isbert), her elderly father, with whom she lives. The old man receives this news the same day he learns that, thanks to his civil service job, he has been assigned a brand new apartment. But then it turns out that, because he’s soon to retire, he’ll lose the apartment even before construction has been completed. So Jose Luis and Carmen marry, the baby is born, and through Amadeo’s urging the younger man takes over his civil service position, thus qualifying for the apartment.

All of this is rendered lightly by Berlanga, who pays close attention to small social details and the petty irritations which inevitably arise when people are forced together in too-close quarters. Here the film has affinities with such neorealist works as De Sica’s Il Tetto; it’s about ordinary people doing what they can to get by and make meagre lives as comfortable as possible with limited resources. The relationship between Jose Luis and Carmen is touchingly developed; her crusty father is treated with great comic affection (Isbert steals virtually every scene he’s in). We very much want these people to succeed.

But Berlanga, and his co-writers Rafael Azcona and Ennio Flaiano, inject one huge complication into this small, familiar story. Amadeo’s job, which he passes on to Jose Luis, is that of official state executioner. Jose Luis, who was previously an undertaker, first encounters the old man when he and his partner arrive at a prison to collect the body of a freshly executed man; they give Amadeo a ride back to town and he inadvertently leaves the bag containing the tools of his trade in their van. Jose Luis has to return the bag and in doing so meets Carmen. She has remained single because no man wants her after he learns about her father’s work. Jose Luis commiserates because, being an undertaker, he too has a hard time sustaining relationships.

Once the couple are married, the film’s comic tone grows steadily darker. Until now Jose Luis had dealt with both the living and the dead, but he has no experience with the moment of transition between the two states. The idea of being responsible for that transition appalls him, even more so because the method of execution is so close-up and personal: the garrote. This is a metal loop attached to a post, through which the prisoner’s head is passed so that the executioner can slowly strangle the victim to death by tightening a screw.

Although Jose Luis has taken the position in order to secure a more comfortable home for himself, his wife and her father, he tries desperately to avoid the work. At one point we even see him intervene in a fight between strangers on the street because he fears that one of the men might kill the other, thus ending up condemned to death. When he finally gets the telegram ordering him to Majorca to perform an execution, Carmen and Amadeo accompany him; when the condemned man falls ill, the family get to stay in a nice pensione by the sea for an extended vacation. Jose Luis desperately hopes that the man will die of natural causes.

But he recovers and Jose Luis is called back to the prison. He tries to resign, but the prison officials won’t hear of it – it would be unkind to the condemned man to make him wait while they found another executioner.

The film’s climax is a nightmarish vision of personal hell as the prisoner is led calmly through a stark white courtyard while his executioner is dragged kicking and fighting to his unavoidable fate.

In The Executioner, Berlanga created a deceptively light and comic vision of ordinary, likeable people trapped by a social and political system which ultimately refuses personal moral autonomy, forcing an essentially harmless guy to become a killer against his own nature. Embedded in the fabric of the film is a horror of the very idea of capital punishment, and by extension the state which demands it, and yet because this critique is conveyed through the forms of domestic comedy, with such sympathetic characters, it managed to slip past the censors, nominated for and winning awards both in Spain and outside the country.

The disk

Criterion’s Blu-ray features a 4K scan from the original negative and Tonino Delli Colli’s lush black-and-white photography has deep blacks and rich levels of contrast which give the image a lot of fine detail. The mono sound is clear, with some depth, and the music score by Miguel Asins Arbo has a deceptively light, slightly jazzy air which adds to the subversive nature of the film by emphasizing the light comedic surface beneath which the darker themes lurk.

The supplements

There are three substantial extras on the disk, beginning with a brief (3:56) but informative introduction by filmmaker Pedro Almodovar, in which he situates the film as one of the most important and influential in Spanish cinema; he speculates that Berlanga, whom he sees as the equal of Bunuel, is less well-known outside the country largely because of a style which is heavily verbal, including many scenes in which multiple characters talk over each other, making it extremely difficult to subtitle them coherently. He also elaborates on Berlanga’s ability to beat the censors by confusing them with a deceptive tone which conceals the deeper, darker nature of his work.

Bad Spaniard (56:38) is a new documentary about the director, featuring interviews with Berlanga’s son (interestingly named Jose Luis), in addition to writers, critics and the director of the Berlanga Film Museum.

La Mitad Invisible (28:21) is a Spanish television show from 2009 in which archival interviews with Berlanga are combined with new material to investigate the film’s importance to Spanish cinema.

There is also a trailer (3:36) which struggles to reflect the film’s tone and content, and an essay by film critic David Cairns in the accompanying booklet.

Comments