Notes on melodrama and film history

Valley of the Dolls (Mark Robson, 1967)

Last week, I mentioned re-reading some of Harlan Ellison’s film criticism, something which coincidentally but hardly significantly connected with re-watching season one of the original Star Trek series, which featured Ellison’s episode The City on the Edge of Forever. Now, also no doubt meaninglessly coincidental, Ellison pops up again with a couple of mentions on Criterion’s release of Valley of the Dolls (1967), which apparently he had a hand in writing. He eventually had his name removed because he objected to certain changes made in the adaptation, particularly the addition of what he deemed a “happy ending”. Given his position as a kind of science fiction eminence grise throughout the ’60s, it seems odd that his chief connection with mainstream studio Hollywood should be a couple of Tinseltown melodramas – Russell Rouse’s The Oscar (1966) and this Jacqueline Susann adaptation the following year.

Somehow I had managed not to see Valley of the Dolls until this new release, although I’ve been a fan of Russ Meyer’s parody/pseudo-sequel Beyond the Valley of the Dolls since I first saw it in 1970. Given its reputation as inadvertently camp trash, I was surprised to see Criterion announce it as part of their “continuing series of important classic and contemporary films”, but assumed that it may be time for a reevaluation. Criterion has certainly lavished a lot of attention on it (there are almost three-and-a-half hours of supplements, plus an audio commentary from 2006 – surely a level of overkill when compared to, say, the paltry single extra on their recent edition of Mizoguchi’s The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum).

Well, I’m not sure even with all this material attached that I’d agree that Mark Robson’s movie is either important or classic, but I will confess to being hugely entertained. Although there’s an old-fashioned feel to the movie – essentially a traditional “women’s film” freed from some of the traditional restraints once imposed by the Production Code – it features premarital sex, adultery, abortion, drug addiction and suicide in its story of five women drawn to and, to varying degrees, destroyed by show business. Anne Welles (Barbara Parkins) leaves small town New England for New York, where she gets a job with a theatrical agency which positions her to observe and become involved in the lives of ambitious singer-actress Neely O’Hara (Patty Duke, making a bid for adult stardom after a long career as a child/adolescent actress), pretty but talentless Jennifer North (a luminous Sharon Tate), and ageing star Helen Lawson (Susan Hayward), whose fear of decline makes her mean-spirited towards Neely (a somewhat crude reiteration of the Margot Channing/Eve Harrington dynamic in Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s more wittily sophisticated All About Eve [1950]). The fifth woman is Miriam (Lee Grant), the very controlling sister/manager of singer Tony Polar (Tony Scotti) who tries and fails to prevent her brother becoming involved with and eventually marrying Jennifer.

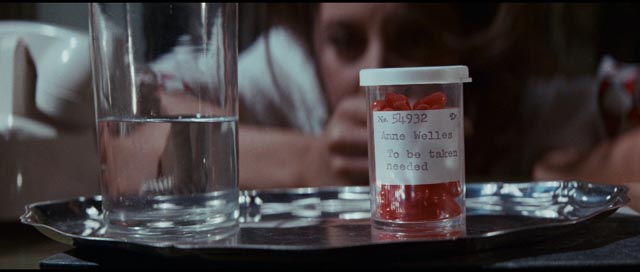

These intersecting lives – somewhat clumsily woven together in a sprawling, episodic narrative which spans an indefinite number of years (though not the two decades of the book) and bounces back and forth between East coast and West, from Broadway to Hollywood and back again – spiral inexorably into a hellish pit of despair. As Kim Morgan points out (in an almost breathlessly enthusiastic video essay on the disk), it can be argued that the movie presents a kind of proto-feminist critique of the opportunities and obstacles faced by women trying to define their own lives; these characters must aggressively assert themselves, but often that aggression is directed towards one another rather than towards the men who try to use them. Lacking in sufficient power to fully control their lives, each ends up making self-destructive decisions: Neely becomes an angry addict hooked on uppers and downers (the “dolls”, as Susann called them); Anne, having resisted submitting to Lyon Burke (Paul Burke), the man she loves who wants her without making any commitment himself, sees him become involved with Neely and then almost dies from booze and pills herself; Jennifer, faced with the loss of Tony to a debilitating hereditary disease, enters a career in French “art films” – that is, porn – in order to pay for Tony’s lingering on in a sanitarium, only to discover eventually that she has breast cancer and is about to lose her chief commercial assets to surgery.

As garish as the story’s elements are, the actresses all give fine, committed performances. Patty Duke, at twenty just coming off three seasons of her successful TV show, is ferocious as Neely, calling up the serious intensity she brought to Arthur Penn’s The Miracle Worker five years earlier. Sharon Tate gives a wistful, sensitive performance as the movie’s one genuinely tragic character; the often underrated Lee Grant conceals deep levels of fear beneath her steely determination to protect her brother; Susan Hayward is almost as fierce as Duke in a fairly standard role as a woman clinging to her position in a business which is prepared to discard her simply because of her age. Barbara Parkins, although essentially the pivotal character, has the most thankless role as the “nice girl” who drifts into this sordid world, is stung by it, but eventually returns to that small town life and her “niceness” at the end.

While Russ Meyer brought a kind of demented glee to similar material in his unofficial sequel, reveling in the cliches and the stylistic filigrees which mocked them, Robson approaches everything with an unimaginative stolidity. The many musical numbers lack vitality, and continuity is ragged – as the story jumps from scene to scene, you get the impression this was probably a longer movie and the length was brought down simply by chopping out chunks of connective tissue. Only occasionally is the kind of imagination and sensitivity Robson showed in his early work for Val Lewton in the ’40s apparent: in Sharon Tate’s sad and bitter suicide scene, and Barbara Parkins hitting bottom with those pills and the booze, staggering down the beach and collapsing at the water’s edge.

Apparently Jacqueline Susann herself thought the adaptation was a butchery of her novel, but she – like the actresses who, at the time, also saw it as an embarrassment – eventually embraced it because it was a commercial success and became something of a cult favourite which boosted sales of the book. But is it really worthy of the Criterion treatment? I guess I’m not really in a position to say as I’ve defended the company’s release of films by the likes of Michael Bay in the past. And in the end, it is, as I said above, very entertaining.

*

The Pleasure-Dome: Collected Film Criticism 1935-40 by Graham Greene

Speaking of re-reading old film criticism, I should mention that I’ve also been skimming through The Pleasure-Dome, a collection of Graham Greene’s reviews from the ’30s which I first read when it was published in 1972. Written for a newspaper called The Spectator, and later briefly for an English attempt at something like The New Yorker called Night and Day, these are journalistic pieces, written quickly in the moment, and that’s what makes them so interesting. Here we get a major writer in the early years of his career responding to pretty much any and every movie playing in London from 1935 to 1940. Many of these films have long since been forgotten, but many more are ones which have become so familiar, so deeply embedded in film history, that it’s hard to think of or respond to them in the same way that a fresh viewer encountering them as new releases would have at a time when (unlike today) there was not much in the way of pre-publicity and raised expectations.

Greene was pretty hard on English productions in those days of quota quickies, even harder on the prestige productions of Korda, which he saw as bloated, unrealistic and dramatically false. He was also hard on Hitchcock, whom he saw as sacrificing any kind of dramatic authenticity for moment-by-moment effects aimed at creating suspense. He was a big admirer of Fritz Lang, but concerned that Lang was in danger of being ruined by Hollywood. From his review of Lang’s You and Me (1938): “For it is impossible not to believe that Lang … has been sabotaged. Given proper control over story and scenario, Lang couldn’t have made so bad a film as You and Me: the whole picture is like an elegant and expensive gesture of despair.” He describes some stylistic touches in the film as “the desperate contortions of a director caught in the Laocoön coils of an impossible script.”

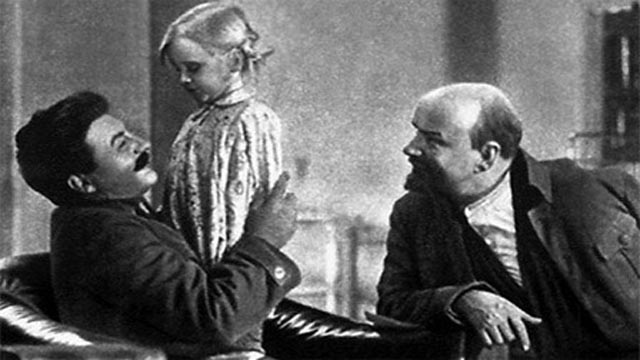

An admirer of early Soviet cinema, by the late ’30s Greene is amused with the corruption which has overtaken Russian filmmaking as Stalinist propaganda twists everything to crass (rather than noble revolutionary) political ends. On Mikhail Romm’s Lenin in October (1937): “History, of course, has to be rewritten in the process, and it would be absurd to expect from Lenin the old excitement of conviction … What is left is the excitement of melodrama handled with the right shabby realism, the interest of seeing an actor reconstruct the mannerisms of Lenin … most agreeable of all the unconscious humour of the rearrangement – the elimination of Trotsky and the way in which Stalin slides into all the important close-ups.”

He doesn’t have a high opinion of James Whale, dismissing The Bride of Frankenstein (1935) as a travesty of Mary Shelley’s creation. Which in essence it is; but now, disconnected from its literary source (I imagine few people still read the novel), we see the film as a masterpiece of poetic and comedic horror. On the other hand, he enjoyed and admired Karl Freund’s Mad Love (also 1935, in England given the title of its source story, The Hands of Orlac), perhaps freed to like it because the French novel it was based on, by Maurice Renard, didn’t have Frankenstein’s literary stature and thus the film could simply be viewed for itself as a stylish horror movie dominated by Peter Lorre in one of his greatest performances.

Greene enjoyed screwball comedies, admired Frank Capra until the misstep of Lost Horizon, liked Harold Lloyd and Harry Bauer, and asserted in 1938 that with the collapse of Soviet cinema “one would name, I think, Julien Duvivier and Fritz Lang as the two greatest fiction directors still at work.” Lang, of course, is still acknowledged as one of the greats, but Duvivier has since all but vanished except for his 1937 romantic crime classic Pepe le Moko (remade twice by Hollywood, in 1938 and 1948), despite a prolific career spanning from 1919 to 1967. Greene’s judgment here highlights the vicissitudes of popular and critical taste; Criterion has attempted to start a revival of Duvivier’s reputation with their release last year of four key films from the ’30s. Hopefully we’ll get a chance to see more of his work. (Criterion subsequently released a restoration of Duvivier’s post-war masterpiece Panique [1946] on Blu-ray.)

There are certain themes discernible throughout the reviews: the fakery of Hollywood, which is not always a bad thing; the financial and creative poverty of the British film industry, with glimpses of hope appearing later in the decade (it seems strange and wonderful to come across a writer of Greene’s stature singing the praises of George King’s The Face at the Window [1939], and hailing Tod Slaughter as one of the country’s greatest living actors); then there is the admiration of French realism, a willingness to look at life in gritty detail rather than idealize it; and there’s praise for the power and poetic imagination of English documentarians – Humphrey Jennings, Edgar Anstey, Basil Wright, Cavalcanti.

Greene’s most famous review is not included in the book, though an appendix reprints the court judgement resulting from the libel suit brought against the writer and his publisher (Night and Day, in this case) for what he wrote about John Ford’s Wee Willie Winkie (1937), in which he mused on the paedophilic aspects of Shirley Temple’s popularity. The lawsuit, settled in favour of Temple and her studio, 20th Century Fox, hastened the demise of the periodical, and it made it impossible to reprint the review in the book. But not surprisingly, it can now be found on the Internet and copied and pasted by anyone interested.[1]

Re-reading these reviews brings back an echo of the excitement of weekly movie-going when the movies were, well, just the movies and not massively hyped pop-culture events. These brief pieces, in their immediacy and spontaneity, serve as a reminder to those of us who steep ourselves in film history and criticism that each movie ever made is a singular thing, turned out into the world in search of an audience, rather than a piece of something larger, whether a particular writer’s, producer’s or director’s body of work (which we tend to see in terms of a meta-narrative in which individual films are building blocks reflecting themes and intentions which exist above and beyond those separate pieces) or a movement or a genre … I know it’s partly nostalgia, but I sometimes think that in knowing as much as we do, we have lost much of the sense of discovery which can be found reflected in these breezy reviews by Graham Greene.

_______________________________________________________________

(1.) “The owners of a child star are like leaseholders – their property diminishes in value every year. Time’s chariot is at their backs: before them acres of anonymity. What is Jackie Coogan now but a matrimonial squabble? Miss Shirley Temple’s case, though, has peculiar interest: infancy with her is a disguise, her appeal is more secret and more adult. Already two years ago she was a fancy little piece – real childhood, I think, went out after The Littlest Rebel. In Captain January she wore trousers with the mature suggestiveness of a Dietrich: her neat and well-developed rump twisted in the tap-dance: her eyes had a sidelong searching coquetry. Now in Wee Willie Winkie, wearing short kilts, she is a complete totsy. Watch her swaggering stride across the Indian barrack-square: hear the gasp of excited expectation from her antique audience when the sergeant’s palm is raised: watch the way she measures a man with agile studio eyes, with dimpled depravity. Adult emotions of love and grief glissade across the mask of childhood, a childhood skin-deep.

“It is clever but it cannot last – middle aged men and clergymen respond to her dubious coquetry, to the sight of her well-shaped and desirable little body, packed with enormous vitality, only because the safety curtain of story and dialogue drops between their intelligence and their desire. “Why are you making my Mummy cry?” – what could be purer than that? And the scene when dressed in a white nightdress she begs grandpa to take Mummy to a dance – what could be more virginal? On those lines her new picture, made by John Ford, who directed The Informer, is horrifyingly competent. It isn’t hard to stay to the last prattle and the last sob. The story – about an Afghan robber converted by Wee Willie Winkie to the British Raj – is a long way after Kipling. But we needn’t be sour about that. Both stories are awful, but on the whole Hollywood’s is the better.” (return)

Comments