Old horrors, newly packaged

I haven’t had a lot of time to write lately, for a number of reasons – including preparing and publishing my two books about David Lynch for sale on Amazon, along with a couple of new volumes of fiction. All four have just gone live: Eraserhead, Dune, Monkey and other stories, and Adios, Elvis or the Secrets of the Universe Revealed.

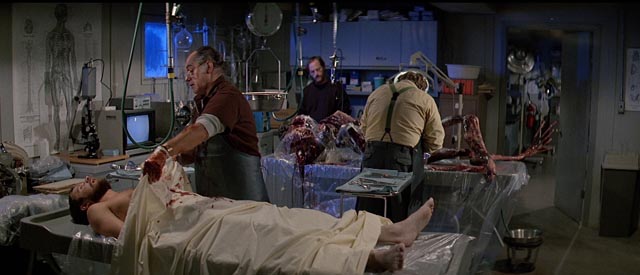

The Thing (John Carpenter, 1982)

On the viewing front, I’ve continued to work through the original Star Trek (taking a break now between seasons two and three), and checked out the new Blu-ray editions of John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982) and William Peter Blatty’s Exorcist III (1990) from Shout! Factory. Both are loaded with extras, many of which I haven’t had time to check out. The Thing remains Carpenter’s best film, and one of the greatest of all monster movies. I’ve always been a bit puzzled by people who complain about the shape-shifting effects created by Rob Bottin and his crew, a kind of condescending attitude towards this approach. Personally, from the very first time I saw the film in 1982, I always feel a sense of wonder; despite years of CGI since then, nothing else in the genre has evoked such a mixture of horror, humour and existential dread.

People who sneer at Carpenter’s movie because it lacks the subtlety of the original Christian Nyby/Howard Hawks version tend to ignore the fact that the remake is actually far more faithful to the source story by John W. Campbell Jr. The whole point of Campbell’s conception was the paranoia resulting from the alien’s ability to absorb and replace anything it came into contact with; in the 1951 movie, this was replaced with what is sometimes dismissively called a “walking carrot”. That film’s strengths lie in Hawks’ patented depiction of an isolated group of no-nonsense guys tackling a difficult situation; but the creature itself is less than satisfying. How did this grunting vegetable manage to build a spaceship and fly to Earth?

In addition, that original monster is a mere physical threat, while in Campbell’s story and Carpenter’s movie (with an excellent script by Bill Lancaster) the fear lies in not knowing who has been transformed into the alien, a creature which skillfully mimics other lifeforms until it has replaced everything within reach; if this creature escapes the Antarctic isolation of the research station nothing can prevent it from replacing every animal and human being on the planet. If the walking carrot gets away from the base … well, it’s really not that big a threat.

Carpenter, a Hawks admirer (his first professional feature, Assault on Precinct 13, was a gloss on Hawks’ Rio Bravo), understands the dynamics of a group dealing together with a threat, but here the nature of that threat undermines the professional solidarity of the men trying to understand and defeat the alien; the remake is propelled by a relentlessly deepening atmosphere of paranoia which leads inexorably to a hopelessly bleak conclusion.

The disk rendering of the film preserves its texture, gritty rather than slick, which adds to the effectiveness of the elaborate on-set physical creature effects. A second commentary track, with cinematographer Dean Cundey, is added to the older track with Carpenter and star Kurt Russell from the DVD edition; a second disk includes the feature-length making-of from the DVD, plus new interviews, vintage featurettes, and the censored network television version.

*

The Exorcist III (William Peter Blatty, 1990)

Coming seventeen years after William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973), and thirteen years after John Boorman’s ill-fated Exorcist II: The Heretic (1977; a film I happen to like more than most people), William Peter Blatty’s Exorcist III (1990) may have seemed somewhat extraneous – but it was nonetheless a fairly effective supernatural thriller with a moody atmosphere and a handful of genuinely good scares. It was also almost as troubled a production as Paul Schrader’s prequel Dominion (eventually released in 2005). However, in the case of Exorcist III, when the producers deemed Blatty’s original cut to be uncommercial, he himself directed all the new material – while in the case of Dominion, the film was taken away from Schrader and completely re-done by Renny Harlin as Exorcist: The Beginning (2004).

The main value of the new Blu-ray edition of Blatty’s film is that it contains both versions – although the original director’s cut is a visual mess because huge chunks of it had to be sourced from a pan-and-scanned VHS copy which is jarringly intercut with parts of the theatrical version. The differences are interesting. In the director’s cut, adapted from Blatty’s own novel Legion, the story centres on weary detective Kinderman (George C. Scott in the Lee J. Cobb role) faced with a series of brutal, religiously-themed murders which seem somehow to be connected to the Gemini Killer (Brad Douriff), who happens to be confined to a psychiatric hospital, where he was taken immediately after the death of Father Karras at the end of the original story.

Gemini is apparently possessed by the same demon, and somehow takes control of various people on the outside to commit new murders. Blatty keeps things fairly low key, and ends the film bluntly with (Spoiler!) Kinderman walking into Gemini’s cell and summarily executing him.

The revised version which was released theatrically received a heavy work-over in order to tie it more directly to the original film, and to ramp up what was perceived to be the main audience draw: possession and exorcism. Lengthy stretches of the scenes which take place in Gemini’s cell were re-shot to bring out the connection between the killer and Father Karras; the priest who sacrificed himself to save Regan is now imprisoned inside Gemini’s body, along with the original personality and the demon. This all creates a stronger personal connection between Kinderman and the prisoner, and adds an element of vengeance to the killings, the victims of which are all in one way or another linked to the detective.

In addition, an entirely new character is introduced: Father Morning (Nicol Williamson) takes the place of Father Merrin, seen throughout the film preparing himself for a final showdown with the demon. Events lead towards a big, loud exorcism in the cell; although all the pyrotechnics tend to overwhelm any more subtle ideas Blatty may be trying to convey, the combined forces of Kinderman and Father Morning on the outside and Father Karras on the inside finally manage to defeat the demon once again.

There’s no denying that the changes forced on Blatty by the producers make the movie more commercially viable. I’d even say that bringing back Jason Miller as Father Karras makes the mid-section dramatically stronger because it creates a closer tie between the detective and the murderous forces at work. But the big supernatural action finale pushes what has been a largely sombre thriller towards trashy exploitation (the impression is similar to the final act of Schrader’s Dominion, where you feel that the exorcism is being imposed merely to tie the film into the franchise). Still, despite its unevenness, Exorcist III is a pretty good movie with a fairly strong cast and its share of creepy moments.

In addition to the two versions, the Blu-ray contains vintage and new interviews, some outtakes and alternate scenes and a featurette on the shooting of the producer-dictated revisions.

Comments