Arrow’s American Horror Project, vol 1

Being a fan is by definition an obsessive thing. It colours judgement; it instills opinion with passion, sometimes critical, more often embracing. I watch movies compulsively because, for perhaps obscure reasons rooted deep in childhood, I’m addicted to the vicarious experiences movies provide. And for whatever other reasons, a good part of that addiction resides in the various forms of genre cinema – fantasy, horror, science fiction, mysteries and thrillers. There’s a ritual element to watching such movies, the play between the familiar and the original. The fan is constantly searching for those movies that provide the most satisfying balance of elements.

One corollary of this condition is a kind of completism, the urge to seek out and see any and every movie in the treasured genre. This can lead to something like my own vast collection of movies (somewhere up around 9000, although I have slowed down in recent years), among which are titles I’d be embarrassed to show to my more refined friends. It can also produce what you might call an encyclopedic impulse, something which has definitely been made more feasible since the dawn of home video. (I’m still in awe of the herculean efforts of Walt Lee, who laboured for years to produce his three-volume Reference Guide to Fantastic Films, published between 1972 and 1974; this attempt to catalogue every movie with a fantasy element made from 1896 to the then present was accomplished in the days not merely before home video access, but also years before computers, and decades before the Internet, made locating this kind of information seem so easy that we no longer give it any thought. This is partly an illusion of course; my friend Howard Curle has been trying for several years now to find more detailed information about the German director Leo Mittler, and more specifically his 1929 silent film Harbour Drift; that information remains mostly hidden somewhere in dusty real-world archives, as yet not uploaded to the web.)

When this kind of obsession blends not only with enthusiasm but also with a degree of critical acumen it produces massive surveys of a genre, like Kim Newman’s Nightmare Movies (1988, revised and expanded 2011). This was Newman’s attempt to build on smaller, seminal works like David Pirie’s A Heritage of Horror (1973) and Ivan Butler’s Horror in the Cinema (1967, revised 1970). The risk in such an undertaking, attempting to create a kind of unified field theory of something as ragged as the horror genre, is that too often (and Newman’s book occasionally slips into this) it can become a mere listing of names and titles. A different approach is taken by books like Phil Hardy’s Encyclopedia of Horror Movies (1986, 1994), which is more of an elaboration on Walt Lee’s approach, cataloguing movies with cast and crew lists, but expanding individual entries with brief critical comments and plot summaries.

This latter approach shies away from positing global theories, gathering disparate individual movies together under a broad genre umbrella, but treating each as essentially a separate critical object. This is what Stephen Thrower did with his hefty coffee-table-sized book Nightmare USA (published by FAB Press in 2007, with a tantalizing final page listing the projected contents of a volume 2 yet to come; I recently heard from Harvey Fenton at FAB that they’re hoping to have that one out in 2018). Divided into two sections, the first 400 pages are devoted to twenty-three chapters focused on particular filmmakers who made independent horror movies in the States between 1970 and 1985, complete with critical comments and interviews; with another 100+ pages of brief essays on a further 118 movies from the period.

Thrower is an enthusiastic writer and researcher, digging up a lot of interesting background information and biographical detail on these filmmakers – most of whom are regional figures far outside the mainstream. But in casting such a broad net, particularly in the second section, he frequently finds himself writing about movies he has a pretty low opinion of. Although they fall within the self-defined limits of the book’s purpose, you can sense his weariness in writing about things he barely had the energy to sit through, and that purely out of a sense of duty imposed by the project he had undertaken. A side effect of this self-inflicted burden is that there are also times when he may seem overly forgiving of other movies which, being thankfully less dire than others, he perhaps treats more positively than they deserve.

This is significant because, in collaboration with Arrow Video, Thrower has embarked on what promises to be a long-term endeavor with the overall name American Horror Project, volume one of which was released this year. I admit to a degree of ambivalence about this dual-format boxed set. The price is a bit high for just three fairly low-budget exploitation movies; but on the up side, Thrower and Arrow have lavished a lot of attention on the films, each disk including a commentary track and various featurettes giving production details and critical and contextual information. Like the book the project is rooted in, this first set points towards a combination of serious film history and the perhaps less reputable pleasures to be found in the murkier depths of that history.

The first volume is a bit of a mixed bag, trying to balance exemplars of the different strata to be found in this cultural archaeological dig. Of course, quite a few of the more prominent – and better – movies from this period are already well-represented on disk (no Texas Chainsaw Massacre here, just as it is omitted from the book as already well-covered elsewhere); this fact alone somewhat complicates the project – Thrower and Arrow will have to shy away from the kind of movies he himself had a hard time watching and writing about, and yet in order to create a fuller picture of the history they must still draw fairly close to the edge of that swamp. And so it is in the first volume that we get one very fine, original and accomplished movie; one fairly ordinary movie with some interesting elements; and one creaky, amateurish movie which seems to hold out more promise than its makers are capable of delivering on.

*

The Witch Who Came From the Sea (Matt Cimber, 1976)

The best film in the set is Matt Cimber’s The Witch Who Came From the Sea (1976); Cimber is a fairly accomplished exploitation director who in this one project managed to rise to a level close to art. The script was written by Robert Thom (who made his mark at American-International with movies like Wild in the Streets and Death Race 2000) for his then-wife Millie Perkins (who had debuted in 1959 in the title role of George Stevens’ The Diary of Anne Frank and had worked with Monte Hellman on The Shooting, Ride in the Whirlwind and Cockfighter) even as their marriage was faltering. Despite the title, this is not a supernatural story, but rather a psychological drama about a woman named Molly (Perkins) who has created an entire fantasy past for herself revolving around her sea captain father, a romantic story about this heroic adventurer, which very soon is revealed as a crumbling defensive mechanism against memories of childhood sexual abuse.

The film follows Molly’s gradual disintegration as the pressures of repressed memory first produce fantasies of violence against highly sexualized men, and eventually actual acts of violence which she can’t distinguish from her own fantasies. Perkins gives a remarkably unguarded performance, strongly supported by Vanessa Brown as her sister Cathy, who has no illusions about their violent alcoholic father; Lonny Chapman as Long John, her boss at a beachside bar; Peggy Feury as her co-worker. There’s no real mystery in the film; the drama and suspense are produced by its detailed depiction of Molly’s deteriorating psychological condition, which is treated with empathy not only by the filmmakers but also by the character’s supportive friends. What is disturbing is the surprisingly frank depiction of the abuse and the specifically sexual nature of the violence which results from it. It was this uncomfortable thematic element which resulted in the film being banned in Britain in the ’80s as a “video nasty”.

With the original elements long ago lost, Arrow had to make its 2K transfer from a slightly battered and faded 35mm print, so the image isn’t as strong as it might have been and a certain amount of damage is apparent; but Dean Cundey’s camerawork has a fluid assurance, evoking Molly’s tenuous hold on reality.

*

The Premonition (Robert Allen Schnitzer, 1976)

Robert Allen Schnitzer’s The Premonition (1976) is a rather restrained thriller which plays on parental fears. Middle class couple Sheri and Miles Bennett (Sharon Farrell and Edward Bell) have a young adopted daughter, Janie (Danielle Brisebois). Janie’s mother Andrea (Ellen Barber) has been away in a mental institution, but now she’s out and she wants her kid back. She teams up with sideshow performer Jude (Richard Lynch), a mime who photographs people at a rundown funfair. In the first of the film’s many coincidences, one day he snaps a shot of Sheri and Janie and shows it to Andrea and the pair hatch a plan to get the girl back.

As is so often the case, the “good” characters are rather bland, a generic suburban couple whose marriage is under strain as the husband is tempted to stray by a co-worker (although Sharon Farrell manages to conjure up some intensity as her maternal instincts are given a workout). The “bad” characters are much more interesting. Andrea is somewhat damaged and fragile, while Jude invests an increasingly psychotic intensity in his plan to reunite her with Janie. For him, this is a way to express a kind of love otherwise left unspoken; but for her it never really rises above a fantasy of the normal life which remains unattainable.

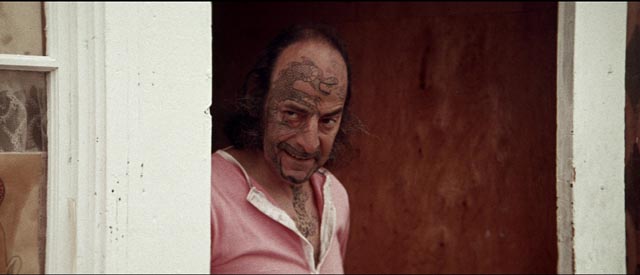

The film’s strongest element is the folie a deux which envelopes Andrea and Jude with tragic consequences. For the rest, events are moved along by coincidences which are vaguely motivated by what amounts to the supernatural force of mother love, giving Sheri visions which gradually draw the two couples closer. Barber is quite touching (and the film can’t quite recover from what happens to her about halfway through), while Lynch is his usual strong, unusual presence. Usually cast as a villain because of extensive facial scarring which was the result of setting himself on fire under the influence of drugs in 1967, he was actually a talented actor capable of emotional nuances which raised many of his roles above cliche and caricature. Here, he’s the strongest presence in the film, eliciting sympathy even as he does terrible things.

Director and co-writer Schnitzer has few credits (including Sylvester Stallone’s first lead in a straight movie, Rebel [1970]). His earlier work consists of documentary-inflected student films dealing with the cultural turmoil of the late ’60s, and he only did one more feature after The Premonition. In one of the extras on the disk, he says that The Premonition expresses his belief in the metaphysical interconnectedness of … well, everything. The coincidences which drive the plot are manifestations of this, giving the story’s events a spiritual meaning. To the casual viewer, these may appear like nothing more than coincidences pushing the plot along. Apart from a few strong sequences (particularly the one in which Andrea sneaks into the Bennetts’ house at night), the main reason for watching is the relationship between Barber and Lynch as a dangerous mirror image of the flawed middle class couple whose own marriage is at risk of disintegrating.

The transfer on the disk is stronger than the one for Witch, with less damage and richer colour values. In addition to Schnitzer’s commentary track and a short making-of documentary, the director’s first three shorts are included, totaling 82 minutes. These all appear to have been shot on 16mm black-and-white stock and, despite indications of a strong visual sensibility, all suffer from editorial weaknesses, playing long and repetitive, with little sense of pace and rhythm. I confess I didn’t make it through the two longer films, Vernal Equinox and Terminal Point, and only stuck with the third, a piece of agit-prop about student protest called A Rumbling in the Land, because it’s just eleven minutes long.

*

Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood (Christopher Speeth, 1973)

With the third film in the set we finally run up against the issues I mentioned earlier. Christopher Speeth’s Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood (1973) is a very low-budget piece of regional filmmaking, shot in Pennsylvania, and largely made to take advantage of a run-down fun fair. But unlike Herk Harvey’s Carnival of Souls, which was also conceived to take advantage of a distinctive location, this is a mess in both concept and execution. It has the air of something thrown together, made up haphazardly bit by bit depending on who showed up on the day. Characters – or rather “characters” – appear and disappear randomly as people seem to fall foul of ghouls or vampires or something …

It would be more than charitable to assert that this is “dream-like”, but Thrower (on the disk, and in his book) and Kim Newman (in a booklet essay) really oversell it. They claim that it’s “beautifully photographed”, but much of it, particularly in the early going, is so poorly framed that you get the feeling cameraman Norman Gaines (whose sole feature credit this is) might not have been aware that the camera was running. They claim that its very incoherence gives it some kind of delirious appeal; I found it merely tedious. The acting is mostly wretched, with Herve Villechaize the only recognizable name.

What the film does have is some interesting do-it-yourself production design by Bruce Millard, Alan Johnson and Richard Stange, making use of found materials (a derelict Volkswagen and rolls of plastic bubble packing material, for instance). But the lack of coherence and momentum make it a hard slog even at only 73 minutes. Yes, it may all be “weird”, but for me there needs to be something more. Even dreams have some kind of internal coherence. This is just a haphazard mess.

But I’m willing to accept its presence in the set because of the overall purpose of the American Horror Project. Malatesta’s Carnival of Blood does represent a particular aspect of regional independent filmmaking and the disk’s extras provide context. In that sense it has a certain academic interest; I now know it exists, but having watched it twice in search of the qualities Thrower and Newman claim for it, I can’t imagine ever watching it again. Perhaps I would have been better disposed towards it if it had been part of a larger set – say one of six films, rather than a full third of this set. Then it wouldn’t have had to bear so much weight or felt quite so overpriced.

Surprisingly, given the movie’s provenance – it had essentially vanished for decades after its initial run, mostly on the drive-in circuit in the early ’70s – despite its unevenness, this is not the weakest transfer of the three. That distinction unfortunately goes to the best film in the set, The Witch Who Came From the Sea. The extras include a commentary by Richard Harland Smith and interviews with director Speeth, writer Werner Liepolt and art directors Richard Stange and Alan Johnson.

*

The real value of a set like this lies in its justifying the release of movies which probably couldn’t stand on their own. Only Cimber’s film is really strong enough to survive on its own terms. If Arrow continues with this project, hopefully Thrower will find more films of this calibre for subsequent sets, and not dip too far into the depths of incompetence which he plumbs so assiduously in his book.

Comments