Time, paradox and loss

I’ve been a sucker for time travel stories since … well, an early age. I was very young when I first read H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine, and I was there at the beginning of Doctor Who, enthralled by the first episode, An Unearthly Child, broadcast at 5:30 on Saturday afternoon, 23 November, 1963 (the day after the Kennedy assassination, for a colossally meaningless coincidence). Already here, it’s possible to see two of the many uses to which time travel can be put: Wells projected his Victorian protagonist into a distant future where class differences and economic disparity have been pushed to satirical extremes; the BBC, at least initially, set out to use it as a device to educate kids about history. That plan quickly collapsed with the arrival of the Daleks and the show became a series of adventures pitting its “family” of travelers against an endless stream of alien menaces.

More often than not, time travel is little more than a narrative device, used for suspense or comedy, to displace a character and present him or her with problems to resolve. I can be somewhat unforgiving when this device is used carelessly. Nicholas Meyer’s Time After Time (1979) is a cherished romantic adventure in which an implausibly naive and somewhat stuffy H.G. Wells (in reality a radical critic of capitalism and an advocate of free love) has his time machine stolen by Jack the Ripper and has to follow the killer to modern day Los Angeles, where he has continued his crimes; while in the city (a perfect illustration of the consequences of the things Wells was prone to criticize) he falls in love and provides many comic fish-out-of-water moments. But the problem for me is a fundamental violation of the underlying time travel premise: if Wells, instead of chasing Jack into the future, had simply used the machine to go back half an hour, he could have prevented Jack from stealing it in the first place, saving a few lives in the process. These kinds of niggling details can play hell with enjoyment of a story for its own sake.

Which is why time travel paradoxes can be so mind-bending, and why they are so tricky to pull off convincingly. Shane Carruth’s Primer (2004) takes paradox as its central theme, with a pair of inventors using the device in a supposedly very controlled way in order to make themselves some money; only time is not so easily controllable and, in one of the key tropes of the genre, various duplicates of the characters begin to interfere with their lives. (This narrative complication was behind one of the “rules” which is commonly found in time travel stories: that it’s not possible for the same person to exist at the same time with another manifestation of his or herself – hence Ron Silver’s gruesome fate in Peter Hyams’ Timecop [1994].) Filmmakers who embrace this duplication effect often produce the most interesting stories – the Spierig Brothers in Predestination (2014), their excellent adaptation of Robert A. Heinlein’s short story “All You Zombies”; Nacho Vigalondo in what is perhaps the purest, most concentrated treatment of the theme, Timecrimes (2007).

The latest attempt to elaborate on this multiplication paradox is Counter Clockwise (2016), a low-budget first feature directed and co-written by George Moise. The influence of Vigalondo’s film is clear, although Moise’s narrative is less tightly focused and his treatment somewhat dilutes with comic overtones the inherent paranoia of the concept.

Co-writer Michael Kopelow plays Ethan, a slightly nerdy techie who has resigned from a large corporation to pursue his own ideas in a private lab he’s set up in what appears to be a big self-storage space. He’s trying to perfect a matter transmitter (a la Seth Brundle in The Fly), but a damaged circuit inadvertently turns it into a time machine. However, he doesn’t realize this even though his test subject, a cute one-eyed dog, doesn’t rematerialize for about five hours. Since the dog reappears in apparently good health, Ethan decides to make himself the next test subject – only to reappear some six months into the future where he discovers that his entire life has gone to hell. His lab is sealed, his house is up for sale, and his pregnant wife is dead … and he’s wanted by the police for her murder.

He manages to deduce, first, that the matter transmitter is actually a time machine, and second that he needs to go back and try to figure out what happened and fix things. Here, of course, we have that typical narrative hitch: if he goes back to before the test with the dog, he can prevent all this happening. But he doesn’t do that. He’s more concerned with playing detective and solving the murder. And in the process, he gradually produces more copies of himself, crossing paths, interfering with events, and generally making things increasingly complicated. The script has a satisfying structure, finding both suspense and humour in Ethan’s situation (though not so much the dark, paranoid humour of Timecrimes), and culminates in a downbeat, open-ended moment of self-awareness on Ethan’s part.

But despite decent low-budget production values and several good performances (particularly Kopelow), there are some tonal issues which keep it from reaching the level of Primer, Premonition and Timecrimes, chiefly some miscalculation in the performances – the bad guys are cartoonishly overdrawn and in at least one instance embarrassingly cliched. Moise also has (what for me at least is) an irritating tendency in the editing to hold too long on certain shots, refusing to cut to the countershot which the viewer is waiting for – this is particularly pronounced in a scene in which the chief villain, Ethan’s former boss, torments him; Moise holds on the guy as he rants, almost foaming at the mouth, but deprives us of Ethan’s reaction to the situation.

On the other hand, there’s a fine twist late in the film when the villain’s motivation is revealed and it turns out to have nothing to do with the time machine Ethan has inadvertently invented.

Overall, the pluses of Counter Clockwise outweigh the minuses and it joins those other paradox movies as an enjoyable variant in a niche genre which is inherently strong in imaginative invention.

*

The passage of time and the inevitability of loss

There have been some notable deaths in the past few months, but to be honest I haven’t felt much like writing about them – maybe encroaching age is bringing the idea of mortality a little too close to home. But ignoring some of these has been weighing on me because not to acknowledge them seems a little like disrespect. So here, a few brief notes:

Lupita Tovar (1910-2016)

A Mexican actress who split her time between Mexico and Hollywood in the ’30s and early ’40s, Lupita Tovar was placed under contract by Fox Studios in 1928 when the arrival of sound inspired Hollywood to make simultaneous Spanish-language versions of many productions. Tovar is now best known for her appearance as Eva in George Melford’s version of Dracula (1931). Although that film lacks the distinctive presence of Bela Lugosi – Carlos Villarias makes for a much less imposing Count – it is in almost every other respect superior to Tod Browning’s movie, with a stronger sense of narrative, and thanks to Tovar a more powerful erotic charge. In 1932, she married producer Paul Kohner; their daughter Susan Kohner was nominated for an Oscar for her performance in Douglas Sirk’s 1959 remake of Imitation of Life. Tovar’s grandsons are Paul and Chris Weitz.

*

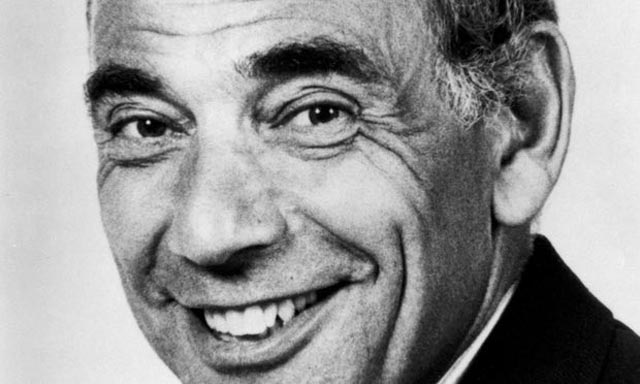

Robert Vaughn (1932-2016)

Although he had a very long and prolific career, mostly in television, and worked right up to this year, Robert Vaughn is best remembered as the suave secret agent Napoleon Solo on The Man From U.N.C.L.E. (1964-68). This series, designed to cash in on the popularity of the James Bond movies, like The Avengers from England (which preceded it by several years), was both homage and send-up of the genre, emphasizing frequently ridiculous plots and a lot of gadgetry. Most of Vaughn’s film work consisted of supporting roles, the best known being gunfighter Lee in The Magnificent Seven (1960), the slick politician Chalmers in Bullitt (1968) and the reprise of his Magnificent Seven role in Battle Beyond the Stars (1980). He was also the voice of sentient computer Proteus IV in Demon Seed (1977). He earned a PhD in 1970 for his dissertation about Hollywood blacklisting during the McCarthy era, and rather incongruously appeared in Coronation Street for a couple of months in 2012.

*

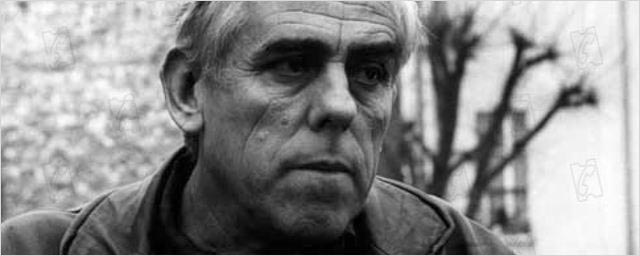

Andrzej Wajda (1926-2016)

As one of the towering figures of Eastern European cinema, Andrzej Wajda’s career spanned six decades, having begun with the remarkable trilogy depicting the Polish experience of World War Two: A Generation (1955), Kanal (1957) and Ashes and Diamonds (1958), films which used a sometimes radical stylistic approach, tying that past into the then present of a country weighed down by Soviet domination. In subject matter, there are echoes of Roberto Rossellini’s War Trilogy, but Wajda eschews the austerity of neorealism for something more stylized which reached its peak in the period-inappropriate persona of Zbigniew Cybulski in Ashes and Diamonds; the actor was more like a cross between Brando and Elvis in full mid-’50s rebellion mode than a plausible resistance fighter in the early ’40s. This reflected Wajda’s ongoing concern with using history to comment on contemporary politics. Having worked steadily for a couple of decades, he became internationally prominent with the release of Man of Marble (1977) and Man of Iron (1981), films which confronted the communist establishment with stories and images which questioned the position of workers within a system supposedly built for their benefit, but too often used to oppress them. After the latter, Wajda became an international figure with Danton (1983), ostensibly about the conflict between Danton and Robespierre in the wake of the French Revolution, but embodying a pointed critique of what was then happening in Poland as the government of Wojciech Jaruzelski confronted the workers’ Solidarity movement led by Lech Walesa. Wajda returned a number of times to the War and its lingering shadow over Polish politics and culture, from A Love in Germany (1983) to Korczak (1990) to the late masterpiece Katyn (2007) in which he finally confronted Soviet atrocities in Poland.

*

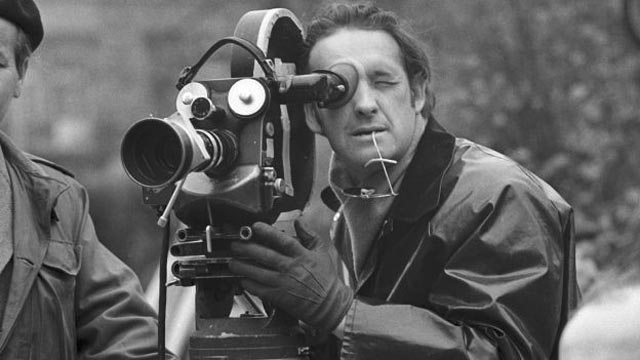

Raoul Coutard (1924-2016)

Cinematographer Raoul Coutard was a key figure in the French New Wave, having shot many films for Godard from Breathless (1967) to Weekend (1967), returning to that collaboration for Godard’s Passion and Prenom: Carmen in the early ’80s; for Truffaut, from Shoot the Piano Player (1960) to The Bride Wore Black (1968); and for Jacques Demy, his first feature Lola (1961). He also contributed to Edgar Morin and Jean Rouch’s Chronicle of a Summer (1961). His contributions to so many of the key films of the ’60s had an incalculable influence on the look of French film during and after the New Wave, and he went on to work with filmmakers as varied as Tony Richardson, Nagisa Oshima and Costa-Gavras. Working into his late 70s, Coutard ended his career with another extended collaborative relationship, with Philippe Garrel.

*

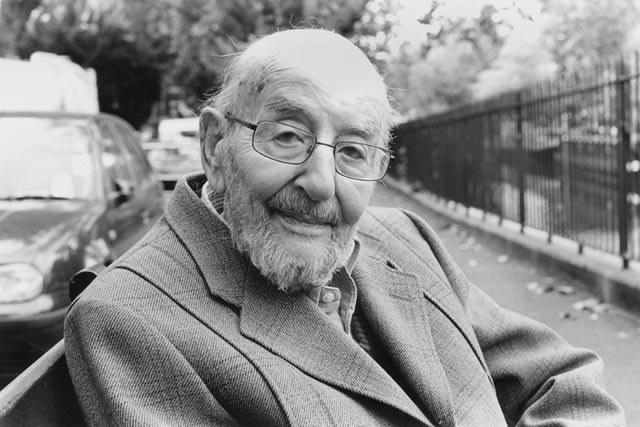

Wolfgang Suschitzky (1912-2016)

Beginning in 1942, the Austrian-born cinematographer Wolfgang Suchitzky was a prolific and influential contributor to the British documentary movement. In the early ’50s, he added occasional dramatic features to his resume, several of which were rare dramatic works by prominent documentarians – Harry Watt, Paul Rotha. Suschitzky’s feature work was eclectic, from Ronald Neame’s adaptation of Joyce Cary’s The Horse’s Mouth (1953) to Jack Gold’s comedy The Chain (1984). He followed Joseph Strick’s version of James Joyce’s Ulysses (1967) with Cliff Owen’s The Vengeance of She (1968) for Hammer; he shot both Entertaining Mr Sloane (1970) and Theatre of Blood (1973) for Douglas Hickox; and perhaps most notably brought a new gritty reality to British film in 1971 with his work on Mike Hodges’ Get Carter, whose bleak northern settings were treated with documentary realism. Wolfgang was also the father of David Cronenberg’s long-time collaborator Peter Suschitzky.

*

At the opposite end of the cinematic spectrum, two icons of low-budget exploitation filmmaking also died recently: Ted V. Mikels and Herschell Gordon Lewis. I have never acquired a taste for the work of either, although both represent a key aspect of the business: an opportunity to make money by exploiting things the mainstream once shied away from in the name of good taste – chiefly sex and violence.

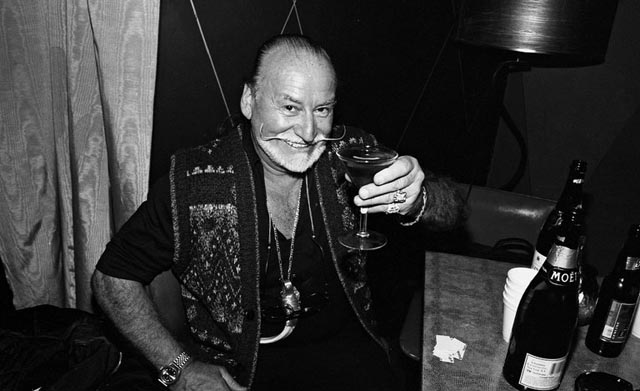

Ted V. Mikels (1929-2016)

I did see Mikels’ The Corpse Grinders (1971) once, back in 1977 or ’78, when I was a student at the University of Winnipeg. The school’s AV department ran lunchtime shows in one of the classrooms in Lockhart Hall, screening 16mm prints of movies it somehow owned copies of. Each movie was split in half, played on consecutive days to fit into the lunch hour. All I can remember of The Corpse Grinders is the painful amateurism, the murky photography, bad acting and ludicrous narrative – or lack of narrative – about an impoverished pet food company which takes to using human bodies in its product, triggering a rash of savage cat attacks when the kitties develop a taste for human flesh. The idea sounds more amusing than the actual execution of it. I’ve never seen any of his more famous movies – Blood Orgy of the She-Devils, The Astro-Zombies (or its no less than three sequels), The Doll Squad – because few pleasures can be found at this level of cheap and bad. Someone like Mikels makes you realize that Ed Wood had something more than incompetence going for him.

*

Herschell Gordon Lewis (1926-2016)

Lewis is a more significant figure. A sometime English literature teacher and one of the founders of direct marketing, he had more than twenty books about advertising and public relations to his credit. He approached exploitation filmmaking from a marketing perspective, identifying under-served niches and creating product to fill them. This started with nudie cuties in the early ’60s, but he and his producing partner David F. Friedman soon found that market too saturated to be particularly profitable; so they sat down to see what the majors were really avoiding and came up with violence – or rather, graphic depictions of violence and gore. With their first attempt, Blood Feast (1963), they hit pay dirt. It didn’t matter that the story was ridiculous (an Egyptian caterer in Miami is slaughtering women in preparation for a cannibalistic “blood feast” aimed at resurrecting the goddess Ishtar), nor that the gore effects were ludicrously unconvincing. What mattered was the attitude, the assault on good taste and giving the finger to the restrictions of the already dying Production Code. What Lewis and Friedman were selling was a category of imagery hitherto forbidden. The quality of that imagery didn’t matter; its mere existence was enough to bring in an audience that was willing to pay to be offended, in fact was eager to revel in the offence.

Lewis punched a hole in industry restraint, paving the way for other filmmakers who eagerly followed his example. He became the “Godfather of Gore”, quickly surpassed by his disciples in terms of quality of effects and often in nastiness of concept. No doubt someone else would have come along eventually to do what he did, but because of his timing and his marketing acumen we could say that his work led to what became the slasher strain of horror and the willingness of someone like Wes Craven (himself a former English literature teacher) to further push the envelope with Last House on the Left (1972), a movie which built on Lewis’ transgressions while adding layers of grim reality and thematic complexity; the offence no longer intended to provide light-hearted fun, but rather to disturb deeply.

For a breezy, somewhat superficial survey of Lewis’ career, see Herschell Gordon Lewis: The Godfather of Gore (2010), a documentary by Frank Henenlotter and Jimmy Maslon.

Comments

Film makers live a long time.

It’s all the chemicals … they’re well-preserved!