Twilight Time round-up

With the Twilight Time Blu-rays piling up, I’m way behind. And perversely, the ones I have been watching are not necessarily the most worthy titles – though each has its points of interest and some are very good indeed. Still waiting on the shelf are John Huston’s Moby Dick and Fat City, Nicolas Roeg’s Eureka, Ivan Passer’s Cutter’s Way, Noel Black’s Pretty Poison and a number of other, older disks. For now, here are a few comments on the ones I have been watching during the past month:

Two starring Frank Sinatra

Following close on the heels of Twilight Time’s release of The Detective (1968) comes a double feature, also directed by Gordon Douglas, featuring an attempt to revive the classic hardboiled detective in the late ’60s. Frank Sinatra stars as Miami private eye Tony Rome in these adaptations of a couple of potboilers by Marvin H. Albert. Both movies have the kind of impersonal gloss that studio productions built around a powerful star, while Sinatra could be seen as either relaxed in his celebrity persona or merely lazily trading on it.

Rome lives on a houseboat, gets involved with rich families who have secrets to conceal, and manages to get away with an awful lot of dubiously legal activities thanks to his personal friendship with police lieutenant Dave Santini (an almost equally relaxed Richard Conte). This doesn’t amount to the kind of rethinking of the genre that Robert Altman achieved when he brought Philip Marlowe into the ’7os in The Long Goodbye. In both films – Tony Rome (1967) and Lady In Cement (1968) – it plays more like a ’60s TV show which merely reiterates the cliches of the genre.

In Tony Rome, Sinatra gets mixed up with the family of an abrasive businessman (Simon Oakland) when the man’s daughter (Sue Lyon) gets drunk at a party, blacks out, and loses a valuable piece of jewelry. Various shady characters interfere with the investigation, thievery and blackmail are unearthed, and a few people are murdered before Rome sorts it all out. Although there’s a casual, by-the-numbers air to the movie (with Douglas occasionally indulging in a crass focus on women’s asses), it does have an excellent cast to provide Sinatra with support: in addition to Lyon, Oakland and Conte, there’s Gena Rowlands as the businessman’s wife, Jill St. John as an attractive divorcee, Robert J. Wilke as a seedy ex-partner of Rome’s, and Lloyd Bochner as a gay fence. Even ex-middleweight world champion Rocky Graziano shows up for a brief scene.

Lady In Cement begins with Rome doing some treasure-hunting scuba diving and encountering a naked blonde on the seabed, her feet in the proverbial cement block. The question of the woman’s identity drags in a variety of characters, including Raquel Welch as Kit Forrester, who is somehow mixed up with supposedly reformed gangster Al Mungar (Martin Gabel), and Bonanza’s Dan Blocker as Waldo Gronski who, despite having no money, hires Rome to find a missing woman for him – who may or may not be the one dumped in the ocean. Blocker adds a comic element which makes this sequel more entertaining than the first movie, while indicating that no one is even trying to take all this seriously.

Neither of these movies has the heft of The Detective, which Sinatra and Douglas sandwiched between the two productions. That film’s conflicted attempt to deal with complicated issues of sexuality is here reduced to casual sexism and homophobic cliches. But as insubstantial as they are, the two movies are breezily entertaining and veteran cinematographer Joseph Biroc ensures that the Miami locations and the glamourous casts supply enough eye candy to justify the ticket price.

*

10 to Midnight (J. Lee Thompson, 1983)

In the late ’50s, J. Lee Thompson made several very good English films – particularly Ice Cold in Alex (1958), Tiger Bay and North West Frontier (both 1959), then in 1961 he made what became a big international hit, The Guns of Navarone. This seemed to sever his connection with his English roots and in the ’60s and after he became one of those efficient craftsmen whose job more often than not was simply wrangling big name casts through commercial properties. There were still occasional distinctive projects like Cape Fear (1962), made immediately after Navarone, and even Conquest of the Planet of the Apes (1972), which particularly in its director’s cut manages to inject some pertinent political commentary into that waning series. But in the last two decades of his career, signs of a directorial personality seemed to disappear under the weight of a string of thrillers, many of which starred a post-Death Wish Charles Bronson.

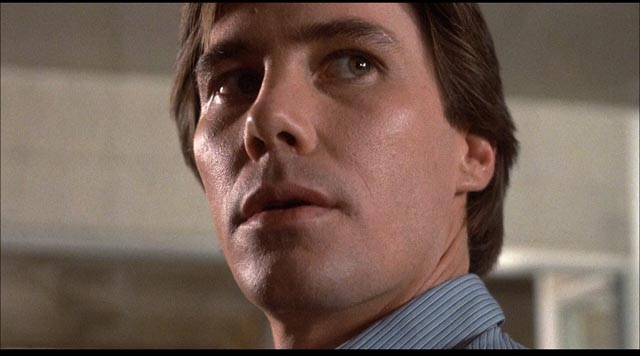

10 to Midnight (1983) was one of these, with Bronson as yet another cop disgusted with the legal constraints which prevent him from bringing in a vicious serial killer. The script was written by William Roberts, who had a few notable credits behind him – including John Sturges’ The Magnificent Seven (1960), Lamont Johnson’s The Last American Hero (1973) and Kirk Douglas’ Posse (1975); he’s also reputed to have had a hand in writing Peckinpah’s Ride the High Country (1962) – and there are some interesting elements, particularly the unsavoury conception of killer Warren Stacy (Gene Davis).

You get the feeling that by this time Bronson was tired of the vigilante role; his performance has little energy. Even though his Detective Leo Kessler is so certain that Stacy is the killer, he has no evidence against him … so he manufactures some, getting himself kicked off the force and drawing the killer’s attention to his own daughter Laurie (Lisa Eilbacher), a nurse. This just makes the case personal, with Kessler in a race to save Laurie as Stacy essentially re-enacts the 1966 mass murder by Richard Speck of a group of student nurses, here the young women Laurie shares a dorm with.

For all the nastiness of Stacy’s crimes, which are shown in some graphic detail, there’s a tiredness about the movie’s cynicism. There isn’t even much kick to its apparent assertion that extra-judicial execution is totally acceptable when a cop is sure he’s got his man. Seen in retrospect, after years of videos catching cops in the act of killing unarmed civilians, the complacency of this movie leaves the viewer with a queasy feeling.

*

Two by Aldrich

One thing you can’t say about Robert Aldrich is that he lacks a distinctive directorial personality. At his best he attacks corruption, hypocrisy and pretension with potent blunt force. He may lack artful finesse, but many of his films are crafted with great skill and energy, their stories fast-paced and their characters both larger than life and psychologically convincing. As a powerful producer-director, his career rose and fell in several cycles from the early ’50s to the late ’70s. The first great period saw a string of excellent movies in several different genres, starting with Apache (1954) and including Vera Cruz (also 1954, and in many ways the prototype for the anti-westerns and spaghetti westerns of the ’60s), Kiss Me Deadly and The Big Knife (both 1955) and the bitter war film Attack! (1956). These films firmly established Aldrich as a particularly masculine director, but in their midst he also made Autumn Leaves (1956), the first in a parallel stream of films centred on women. It starred Joan Crawford, who would have a late career revival thanks to Aldrich’s unexpected 1962 hit What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?

Baby Jane also helped pull Aldrich out of a creative and commercial slump, energizing him for a few good years in the mid-’60s – Hush … Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964), The Flight of the Phoenix (1965), and his biggest commercial success, The Dirty Dozen (1967, possibly his most artless movie, and one which plunges tediously into a kind of self-parody. There were some more stumbles before his recovery in the ’70s with his Vietnam-era western Ulzana’s Raid (1972), followed by Emperor of the North (1973), The Longest Yard (1974), Hustle (1975) and Twilight’s Last Gleaming (1977). These latter films, despite their various flaws, showed the director who had forged his own path in late-classical Hollywood maintaining his energy and identity in the wilder post-studio industry of the ’70s.

Twilight Time in 2016 released two of Aldrich’s movies from these last two phases of his career – Charlotte and Emperor, the first from his female-centred stream, the second virtually the definition of violence-centred masculinity.

Hush … Hush, Sweet Charlotte was conceived as a deliberate follow-up to What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? The script was by Henry Farrell (who wrote the source novel for Baby Jane) and Lukas Heller (who had adapted the earlier film); it was initially to star both Bette Davis and Joan Crawford, but the latter left the production after shooting had already started, and was replaced by Olivia de Havilland; it was again shot in widescreen black-and-white (this time by the prolific Joseph Biroc, who had worked with Aldrich a couple of times in the ’50s and would go on to shoot many of his remaining movies); and once again it revolved around deranged female characters whose lives are overshadowed by a traumatic event deep in the past. But Charlotte is more Southern Gothic than Grand Guignol, and it doesn’t reach the heights of derangement that Baby Jane scaled. In fact, in story terms it more resembles the movies Joan Crawford made with William Castle, starting right after she left Aldrich’s production.

The lengthy prologue, set in 1927, deals with Big Sam Hollis (Victor Buono), young Charlotte’s father, discovering that she’s about to run off with John Mayhew (Bruce Dern), a married man; Hollis pressures John to cut off the relationship, and that evening, while a ball is in progress at the big house, John tells her he’s no longer interested; moments later, someone shows up to chop him to pieces with an axe. A traumatized Charlotte walks into the big party, her white dress drenched in blood. As in Baby Jane, the actual details of the event are obscured, allowing uncertainty about who’s guilty of what. People believe that Charlotte killed John; Charlotte believes that her father did it … the actual truth is revealed late in the story, altering our interpretation of what’s been going on.

The main action of the film takes place in the early ’60s, with the reclusive Charlotte (Bette Davis) living alone in the decaying mansion with her crusty companion/housekeeper Velma (Agnes Moorehead). The state has appropriated the property for a new highway, but Charlotte holds off the wrecking crew with a rifle. At the request of old family friend Dr. Drew Bayliss (Joseph Cotton), Charlotte’s poor cousin and childhood friend Miriam (de Havilland) arrives to help persuade her to move out. Strange things begin to happen – ghostly music is played, Charlotte sees John’s severed hand on the floor, and eventually encounters his cut off head.

Although the mystery is eventually resolved and the real bad guys are appropriately punished, the narrative remains somewhat mechanical, that resolution not as firmly embedded in, or illuminating of, the characters’ twisted psychology. While Baby Jane ends on a note of tragedy, Charlotte just feels neatly wrapped up and superficial. But on the level of craft, it’s excellent; the cast give fine performances and Biroc’s photography is richly atmospheric. What it lacks is the presence of Baby Jane’s larger-than-life human monsters; perhaps in compensation for the grotesquerie of her character in the earlier film, Davis here remains feisty and sympathetic throughout.

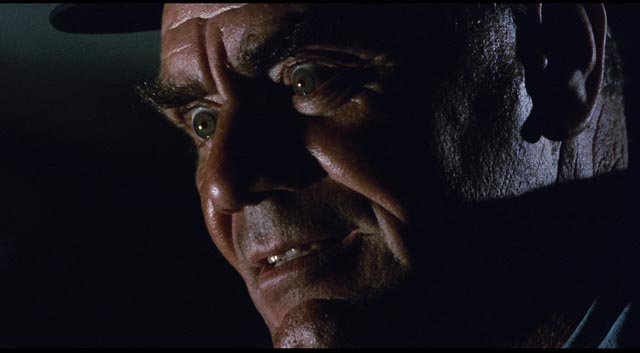

Emperor of the North, on the other hand, gleefully wallows in the grotesque. A melodrama of hyper-masculinity, it’s a catalogue of brutality set in a majestic landscape, lending a mythic quality to the chest-thumping conflict between a sadistic railway guard and a hobo determined to proclaim his natural right to freedom and independence. Masculinity here is a matter of power and territoriality – in essence, reduced to its basic animal component. Shack (Ernest Borgnine) has no other reason for violently keeping hobos off his freight train in the Depression-era northwest than that it’s “his train”; A Number 1 (Lee Marvin) has no reason to try to ride that train other than to assert his dominance over Shack. They’re a couple of rams crashing their heads together, but not to take possession of the herd … merely to prove to all the (male) observers, trainmen and hobos, who’s the alpha.

Their game plays out along the line through the rugged mountain forests of Oregon, providing a spectacular visual backdrop for what amounts to a series of violently escalating confrontations. Aldrich directs the action with energy and precision (unlike the messy staging of The Dirty Dozen), and Marvin and Borgnine are at their best in parts which are more mythic than realistic. The cast is packed with great character actors (even Elisha Cook Jr pops up for a brief appearance), but the standout is twenty-three year old Keith Carradine in his first major role as Cigaret, a cocky, boastful hobo who seems to want to learn from A Number 1, but really just wants to claim the glory without making any effort. As the third part of this triangle, he shows through his lies and hypocrisy that A Number 1 and Shack are two of a kind, honest in their high-testosterone competition; although Shack functions through sheer brutality, while A Number 1 is a wily trickster, both are authentic … at least in comparison to the underhanded faker who plays them off against each other in his quest to claim the reputation as the only man capable of riding Shack’s train.

Christopher Knopf’s script could easily be schematic and one-dimensional without these three lead performances; with them, Emperor of the North becomes one of the finest films Aldrich made in the final decade of his career.

*

The Chase (Arthur Penn, 1966)

The first – and until now, only – time I’d seen Arthur Penn’s The Chase (1966) was on TV sometime in the early ’70s. Whatever movies-on-TV guide I was using at the time (Steven Scheuer, Leonard Maltin or whatever) lead me to believe that it was a misconceived failure. There are no doubt valid arguments for saying it’s misconceived, and the director himself dismissed it as a failure because producer Sam Spiegel had taken it away from him and edited it without Penn’s input. And yet, it is nonetheless an interesting film, a precursor to the dark and cynical post-studio productions of the ’70s which cast a very sour eye on contemporary America.

I have no idea what changes were made to the source material, a novel and play by Southern writer Horton Foote, but the original adaptation by Lillian Hellman was reworked by multiple hands under Spiegel’s supervision, and the end result is a steamy Southern melodrama along the lines of Otto Preminger’s Hurry Sundown (1967), which itself was co-scripted by Foote. When local bad boy Bubber Reeves (Robert Redford) escapes from jail, every level of society in a small Texas town is stirred up – by fear, resentment, and a general primal urge to express violent impulses. Bubber was launched on his life of crime when he was blamed as a kid for something done by Edwin Stewart (Robert Duvall); his wife Anna (Jane Fonda) is having an affair with his childhood best friend Jake Rogers (James Fox), bitter son of the town’s big wheel Val Rogers (E.G. Marshall). Although Bubber intends to get away to Mexico, fate draws him back to the town, triggering events which Sheriff Calder (Marlon Brando), apparently the only ethical man in the county, is powerless to stop.

As overheated and pulpy as the story is, Penn draws excellent performances from his big cast as he paints a portrait of a society rotten to the core; those who aren’t completely corrupt are too weak to do the right thing and events climax in an apocalyptic conflagration, which in turn is capped by a startling visual reference to Jack Ruby’s public murder of Lee Harvey Oswald, which had happened only a couple of years before the film was made.

It’s impossible to know how different Penn’s edit would have been, although it’s hard to believe that he could have given this material greater gravity; the story doesn’t really lend itself to more serious drama. But as melodrama, it’s firing on all cylinders, stirring up a visceral emotional response in the viewer with its depiction of social inequality, racism, and the vicious hypocrisy of the town’s “good citizens”.

The Chase is actually much better than my memory of that earlier viewing, not least for the atmospheric widescreen photography of Joseph LaShelle which gives the narrative a sense of scale not apparent in a pan-and-scanned TV transfer. And the cast keeps it interesting from start to finish; although Brando is inevitably dominant, he doesn’t overshadow the ensemble which also includes Miriam Hopkins, Henry Hull, Angie Dickinson, Janice Rule, Martha Hyer, Richard Bradford, Diana Hyland, Jocelyn Brando, Bruce Cabot, Steve Ihnat, Malcolm Atterbury, Clifton James …and even Paul Williams in his small second role.

*

The Boston Strangler (Richard Fleischer, 1968)

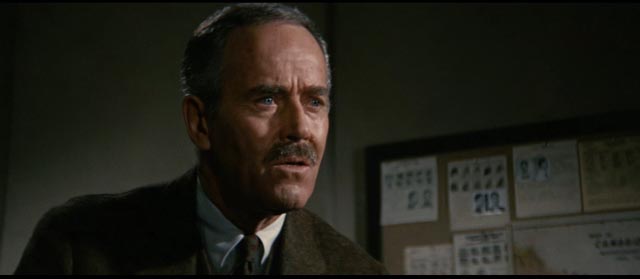

Richard Fleischer’s The Boston Strangler (1968) is problematic in a different way. Made just a few years after a series of brutal murders in and around Boston created paranoia and panic, the film was based on a best-selling book by journalist Gerold Frank, with a taut script by Edward Anhalt, and a cast headed by Henry Fonda as John S. Bottomly, the head of the investigative team, and Tony Curtis as Albert DeSalvo, the ostensible killer. Curtis lobbied hard for the part because he wanted to break out of his image as a lightweight romantic comedy star and Fonda gives the film the low-key gravitas which was important in getting the sordid material past industry watchdogs.

At the time it was made, it was believed that DeSalvo committed the thirteen murders – women in all age ranges who, despite the reign of terror, for some reason let the killer into their homes – even though he was never charged, tried or convicted. The belief in his guilt was based on a confession he made, but doubt has subsequently been cast on the case, with the killings possibly being the work of more than one man.

The film is structured into two distinct parts: the first half deals with the murders and the growing panic which permeates the city. Fleischer brings a kind of documentary detachment to the material, treating it matter-of-factly. But while the tone is objective, he applies what at the time was a trendy, perhaps already overused technique – splitting the screen up into multiple images (also used extensively that same year in Ralph Nelson’s Charly and Norman Jewison’s The Thomas Crown Affair). This allows him to cram a great deal more visual and aural information into limited space, adding an air of uncertainty as the viewer scans those images for what may or may not be crucial pieces of information. It also lays the thematic groundwork for the film’s treatment of the killer.

DeSalvo is introduced halfway through the film, a working man, an apparently loving husband and father, who has an overwhelming compulsion to kill. Where this compulsion comes from is never dealt with – instead, we are told that DeSalvo is a divided (split) personality, that there are two of him inside the same body, the ordinary guy unaware of what the other one is up to. After he is caught, purely by accident, Bottomly conducts a series of interviews through which he attempts to get DeSalvo to become aware of his own crimes. Psychiatrist Dr. Nagy (Austin Willis) warns that breaking down the wall between the two halves could destroy DeSalvo, but Bottomly forges ahead – because there’s no physical evidence that he’s the killer, he wants to do whatever he can to establish his guilt so that everyone can be sure the killings will stop.

The final extended sequence is a tour-de-force, with Curtis re-enacting one of the murders in the interrogation room, gradually becoming conscious of what he’s done and finally retreating into some inner place where he can no longer be touched.

The thing is, the script alters a number of things – including DeSalvo’s job and his past history as a petty criminal rather than simply a decent working man, not to mention that he was never diagnosed with multiple personality disorder – as well as offering no doubt about his guilt. From a documentary point of view, this is all pretty dubious, even more so given the subsequent doubts about DeSalvo’s guilt. Fleischer’s previous “true crime” movie, Compulsion (1959), was a fictionalized account of the Leopold and Loeb case of 1924, but in that case names were changed and it didn’t make such a forceful effort to appear factual (despite a fine cast, that film was undermined somewhat by the impossibility of exploring the underlying sexual dimension of the killers’ relationship).

The Boston Strangler, however, presents itself as a true story ripped from recent headlines, representing actual events and people who were still around at the time. This raises moral and ethical questions which can’t be brushed aside by the fact that Fleischer directs the film with great skill and that his cast deliver strong, committed performances. The problems suggested by “based on a true story” or “inspired by true events” are well known, but in this case the filmmakers were creating a very particular and detailed portrait of a man who, it now appears, may well have not been the killer, let alone a psychotic with multiple personalities. This gives the film in retrospect a rather sordid aura, exploiting horrific events to provide the audience with a frisson supposedly justified by its purported objectivity.

And yet The Boston Strangler is so well-crafted that as a movie it’s an impressive piece of work, and certainly Fleischer’s most stylistically adventurous project. Almost as good as 10 Rillington Place.

*

All these Twilight Time Blu-rays feature commentaries and isolated music tracks, and Hush … Hush, Sweet Charlotte and The Boston Strangler each also include several featurettes.

Comments