Canoa, A Shameful Memory (1976): Criterion Blu-ray review

Even with the increased availability of films on disk over the past couple of decades, my knowledge of many national cinemas remains sketchy. Often access is limited to those films and filmmakers who have attained international reputations through festival success and the advocacy of prominent critics, or conversely to movies which tap into audience tastes for various popular genres. In the case of Mexico, for instance, from the “classical period”, I know little beyond the features Bunuel made there in his long exile, and the atmospheric and sometimes deranged horror films of Chano Urueta and Fernando Mendez, with occasional tangents into the realm of the masked wrestler Santo and vengeful Aztec mummies.

Then there was the major wave of new filmmakers in the ’90s and early 2000s – Guillermo del Toro, Alfonso Cuaron, Alejandro González Iñárritu, Carlos Reygadas and others. But the question of how Mexican cinema evolved from the ’60s to the ’90s is something I hadn’t given much thought. It’s a question partially answered by the Criterion release of Canoa: A Shameful Memory (1976), written by Tomás Pérez Turrent and directed by Felipe Cazals, a stylistically radical dramatized account of an incident which occurred in 1968 in the village of San Miguel Canoa.

The disorienting effect of the film is only partially due to a lack of familiarity with Mexican history in general and with the specific events depicted in particular. Cazals uses various techniques to create an alienating experience for the audience; the events themselves are deeply disturbing, but the filmmakers resist playing on viewer emotions. Brechtian devices maintain a sense of objective distance which gradually imposes a feeling of horror – paradoxically, by withholding editorial comment on the events, the film forces viewers to summon up their own outrage. This is not at all like, say, the political thrillers of Costa-Gavras which skillfully use well-honed manipulative narrative techniques to direct the audience towards particular conclusions. Canoa demands a deeper, more personal political response.

The events depicted are these: five young employees of a university take a trip to San Miguel, intending to climb and camp on a nearby volcano. Arriving in the evening, they find themselves stranded by a rainstorm and seek a place to shelter for the night. But the local population is deeply suspicious. Largely illiterate, they are controlled by a priest who has filled them with fear of outsiders. This was 1968 and Mexico was in the midst of the same social and political upheavals experienced by so many countries in Europe and North America. The repressive government of the PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party) had been in power since 1929 and universities were now centres of opposition. As elsewhere, that opposition was labelled communist agitation and in a country like Mexico where the Church held so much power over the population, protesters were seen as godless criminals.

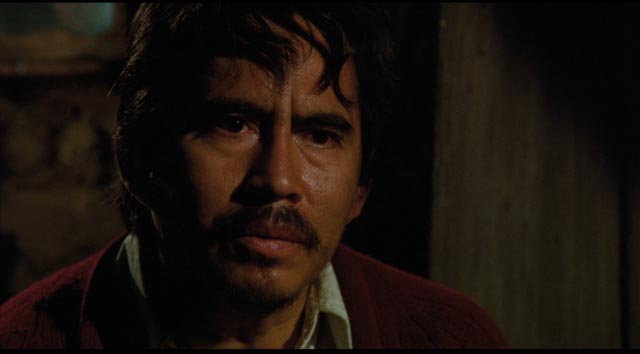

The priest (Enrique Lucero) has convinced the people of the village that students from the university will be coming to take away their religion, to desecrate their church, so when the five employees unwittingly mention that they’re from the university, a wave of fear pours through the village, stirred up by the priest, and a mob quickly forms. Two thousand villagers track down the workers and savagely attack them. Cazals is unflinching in his depiction of the violence, a welling up of medieval fanaticism, the purging of heretics …

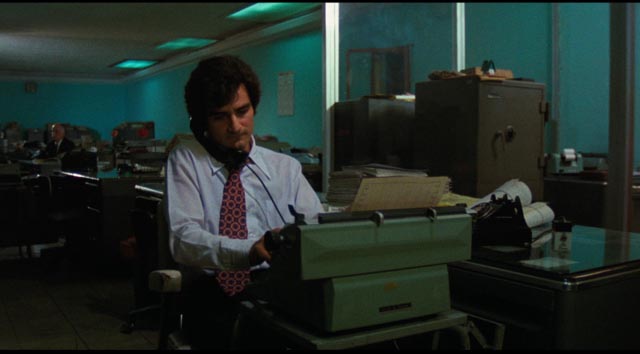

While the entire final section of Canoa has the oppressive atmosphere of a horror film, it begins with an air of documentary objectivity. In the opening scene, a newspaper reporter receives a phone call and begins typing notes on what he is being told. It’s a stark account with few details about five university workers who have been lynched in a small town. The opening titles follow this against a background of black-and-white images of police standing over brutalized bodies. And this in turn segues to interview clips with people from the village. But these last are staged; these are obviously actors providing the background information about the village and the internal conflicts which have led to the violence. The artificiality of the “interviews” immediately creates distance from the initial shock provided by the sketchy account of the incident.

As we receive this information about the village and the tight grip of the priest over the peasant population, and hear that those who oppose him are treated with hostility, Cazals begins to shift back and forth in time. The “interviews” reflect back on the incident, while events leading up to it are dramatized. We are introduced to the university workers, who bicker and joke amongst themselves as they plan their trip. We don’t learn much about them as individuals, but we do come to see that they are naively insensitive to the people around them – their rowdiness on the bus to San Miguel annoys the other passengers and their defence is that they’re just having fun; when they reach the town, they pay little attention to the chilly reception they receive in a little shop where they continue to be rowdy.

They are turned away when they ask for shelter for the night at the church; the priest is vaguely apologetic but says that because he doesn’t know them, he can’t trust them not to damage the place. Then when they find shelter with a local man and his family, who dislike the priest, the priest and his supporters begin to stir up the population with accusations that communist students have come to desecrate the church and “take away” their religion. Even as this is announced over the village’s loudspeakers, the workers don’t make the connection with themselves and they are completely unprepared when a large mob arrives and lays siege to the house in which they are sheltering.

Even during the horrific events which follow, Cazals repeatedly interrupts the action with more interview clips, including with the priest who distances himself from any responsibility for what happened. The cumulative effect is to draw a sense of moral outrage out of the viewer while clearly establishing the social and political mechanisms of control which lie behind what seems to be an eruption of uncontrolled violence.

Although it’s not clear from the film itself (to a viewer without knowledge of the larger situation at the time), Canoa was a remarkable attack on the Mexican state through oblique means. The very helpful supplements on Criterion’s disk fill in this context, in particular a massacre in Mexico City a couple of weeks after the incident in Canoa in which the military killed hundreds of protesting students. While on their surface the events in the film are depicted as the actions of superstitious peasants, it is made very clear that the power held by the priest over those peasants is closely allied with the power of state authorities. The attack on these five workers is an inevitable result of the state’s demonization of its opponents.

What is perhaps most remarkable is that this scathing critique of church and state was produced with government funding. Although the PRI was still in power, President Luis Echeveria (who, as secretary of state in 1968, was responsible for the student massacre) didn’t oppose the film; and the president’s brother Rodolfo Echeveria was in charge of the National Film Bank which provided production funds. The film played at international festivals and had a commercially successful run in Mexico. It was during this run that future filmmakers like Alfonso Cuaron and Guillermo del Toro first encountered Canoa, seeing radical new possibilities in Mexican cinema which eventually emerged as the new wave of the ’90s.

Despite the specificity of the film’s subject, it has a chilling contemporary relevance in its depiction of the ways in which propaganda (“fake news”) binds political and religious ideologies to create an atmosphere of fear with the resultant demonization of various “others” who can be branded enemies of the people and targeted for violent expulsion from society.

The disk

Criterion’s new 4K restoration from the original camera negative has rich colours, excellent contrast and a dense film-like texture. The remastered mono soundtrack is clean, with dialogue clearly rendered. There is no music score; the track relies on natural ambiences to create its air of increasing dread.

The supplements

The most substantial supplement is a lengthy (54:41) conversation between director Felipe Cazals and Alfonso Cuaron; the latter is extremely enthusiastic about Canoa, drawing interesting comments from Cazals about the film’s genesis and his approach to the production.

There is also a brief introduction from Guillermo del Toro (3:30) and a trailer (4:50).

The informative booklet essay is by Mexican film critic Fernanda Solorzano.

NOTE: There is one detail in the film which is unexplained by any of the supplements. In the original incident (and in the account initially received by the reporter in the opening scene), four of the workers were killed, with just one surviving. But at the end of the film, there are three survivors.

Comments

Thank you for your article. In response to your note at the end, it is important to remember that those who housed the workers on 9-14-68 were also put in danger, harmed, and even killed. Those who died during the incident were Lucas, a resident of San Miguel Canoa, Jesus Carrillo Sánchez, a worker, Rameon Calvario Gutiérrez, a worker, and Odilón Sánchez Islas, another resident. The three survivors with whom Pérez Turrent spoke in 1974 are Julián García Baez, Miguel Flores Cruz, and Roberto Rojano Aguirre. The survivors with whom Pérez Turrent spoke were all workers attempting to hike La Malinche.