Viewing notes: May 2017

Japanese animation is so extensive and varied that the term anime seems too limiting, particularly as it conjures in most people’s minds endless TV series, characters with huge eyes (and for the females frequently large breasts and short skirts), mostly grounded in fantasy, horror or sci-fi. These shows range from Sailor Moon to Mobile Suit Gundam, Gunslinger Girl to LAIN, Devilman to Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex and countless others of wildly varying quality. But then there are the movies of Studio Ghibli, epic fantasies, subtle dramas, satirical comedies, all created with an exquisite sense of the artistic possibilities of animation … these and other films in their class seem somehow diminished by the label “anime”. It’s like lumping the works of Kurosawa, Naruse, Kinoshita, Takashi Miike and Sono Sion under a single designation of “live action”. In the end, it doesn’t really inform us of what to expect when we encounter individual works.

Patema Inverted (Yasuhiro Yoshiura, 2013)

I recently watched two Japanese animated movies, neither of which I had heard of before I encountered them on Blu-ray. Yasuhiro Yoshiura’s Patema Inverted (2013) may suggest the influence of Juan Solanas’ Upside Down (2012), but in place of that misfire’s leaden execution, it has a lightness of touch and richness of imagination which give its core gimmick a real dramatic and emotional force. In this world, at some point in the past, a scientific experiment went awry, reversing gravity and sending much of the population (and infrastructure) soaring out into space. Those who were unaffected have fearfully created a repressive, fascistic society which demands absolute conformity and bans imagination and independent thought. Meanwhile, below ground, a small society of “inverts” live in caves and tunnels, their reversed gravity causing them to walk on what we would see as ceilings, while any trip to the surface threatens to launch them into the sky.

Patema (voiced by Yukiyo Fujii) is an adventurous, unruly invert girl who has been filled with a desire to explore beyond the limits of her enclosed world. When she reaches the surface, she barely saves herself by hanging onto a wire fence, her feet pointed at the sky (her “down”). By coincidence, this happens in front of Age (Nobuhiko Okamoto), a schoolboy who, against all rules, wanders out of the city at night to lie and look up at the lights in the sky (looking up is forbidden). He manages to grab hold of Patema, their conflicting gravities giving them a combined lightness which makes it possible to leap great distances; he gets her to a nearby shed, where once inside she can safely stand on the ceiling.

Patema’s presence and Age’s rebellious attitude draw the attention of the dictator and his security forces; he sees this as an opportunity to track down the remaining inverts who live beneath his city. The young pair face numerous dangerous situations, but the bond they forge begins to break down the rigidity of the two competing worlds, ultimately dispelling the fear which has kept them separate.

Apart from the well-conceived conceptual world and engaging characters, what makes Patema Inverted a really terrific feature is Yoshiura’s dexterity in handling the constantly shifting sense of up and down; the film is visually stunning and vertiginous, disorienting and dizzying as the camera continuously orients and reorients itself; through its visual conception it forcefully breaks down the false dichotomy the two societies have wilfully created to keep themselves separate and isolated. Here style and theme are inextricably linked in one of the best animated features of recent years.

*

Miss Hokusai (Keiichi Hara, 2015)

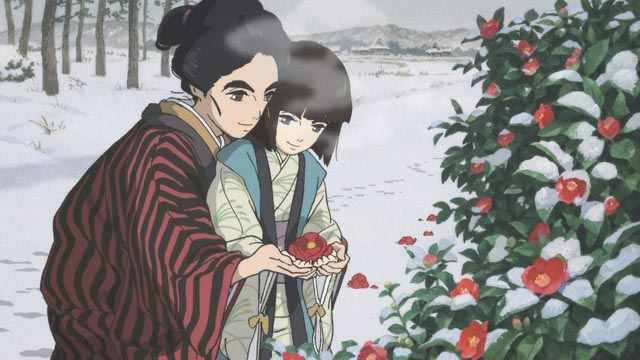

In some ways, you couldn’t get farther from Patema Inverted than Keiichi Hara’s Miss Hokusai (2015). Adapted from a manga by Hinako Sugiura, which was based on the life of O-Ei, the daughter of the great 19th Century artist Hokusai, the film has a delicate yet finely detailed visual style rooted in Japanese painting. O-Ei, an artist herself, lives with her father, her own creativity overshadowed as she aids him in his work. Miss Hokusai is a film of subtle moods rather than big events, with acute observation of the psychology of a woman living an unconventional life in a society with rigidly defined gender roles.

The heart of the film is O-Ei’s relationship with her blind younger sister O-Nao, who lives with their mother, her existence all-but ignored by her father. O-Ei’s vision of the city and the seasons is subtly informed by vicariously observing her surroundings through O-Nao’s senses – sound and touch providing experiences different from sight. Watching O-Nao playing in the snow with a boy who responds creatively to her blindness provides a glimpse of innocence unspoiled by the more mundane demands of her own life with her father.

There are moments when traces of the supernatural impinge on O-Ei’s world, with spirits appearing as a quite ordinary aspect of life, but Miss Hokusai for the most part is a quiet, naturalistic character study, belonging to that strand of Japanese animation which uses the medium to tell stories which could as easily be done in live action (like Isao Takahata’s Only Yesterday [1991] or Goro Miyazaki’s From Up On Poppy Hill [2011]), but which nonetheless use the particular qualities of hand-drawn imagery to create delicate moods which transcend the physical reality of actors and physical settings.

Both films have been released on disk by Gkids/Universal. While there are a few brief featurettes on the Patema Inverted Blu-ray, the Miss Hokusai release includes a two-hour Making Of which is surprisingly revealing. Director Keiichi Hara suffered a kind of breakdown partway through production from the strain of what he felt to be an overwhelming responsibility to honour the work of Hinako Sugiura; taking a brief break in the task of creating the storyboard which forms the basis of the film, he eventually disappeared for six months. The team of animators continued to do their work, but without his direct guidance … and with the entire final section of the film still unknown. When Hara finally returned, looking more frail and uncertain, there was a pressing deadline to meet. Although he did complete the storyboard (including a very difficult and demanding extended sequence for which he wanted all the detailed backgrounds to be hand-drawn rather than created with CG), and the animation team managed to complete their work seemingly with moments to spare, there was no time to make some changes he wanted. Considering the uncertainty which hung over the production, it’s remarkable how light and unforced it seems. Beyond this personal drama of Hara’s creative struggle, the documentary offers a detailed look at the animation production process itself. It’s an excellent companion for a film about an artist’s struggle to find the balance between creativity and life.

*

Caltiki: The Immortal Monster

(Riccardo Freda & Mario Bava, 1959)

Although Mario Bava was uncredited as one of the directors on Caltiki: The Immortal Monster (1959), it is recognized as one of the important steps on his way to a full-fledged directing career which began officially with Black Sunday the following year. As with several films which preceded it (and even with some which followed his directing debut), he was officially hired as cinematographer and visual effects technician, the latter role involving a more active directorial presence. The movie Caltiki has most in common with is I Vampiri (1957), which like Caltiki was begun by Bava’s friend and colleague Riccardo Freda who in both cases left the production before completion, with Bava stepping in to complete (and to some degree patch together) the film.

Caltiki might lack the high concept of Patema Inverted and the delicate artistry of Miss Hokusai, but Bava managed to stretch the very limited budget with his remarkable skill for creating rich imagery from very little. Made at a time when home-grown Italian fantasy and horror movies were still rare (I Vampiri was essentially the first Italian horror movie of the sound era), it was influenced primarily by three recent foreign releases – Hammer’s The Quatermass Xperiment (Val Guest, 1955), the studio’s self-plagiarization of that hit, X the Unknown (Leslie Norman, 1956), and Irvin S. Yeaworth Jr’s The Blob (1958). Despite the budgetary limitations and a clumsy script, it still stands as a fine example of the “amorphous blob” sub-genre.

After a visually lush title sequence which consists almost entirely of multi-layered glass shots executed by Bava combined with a volcanic eruption created with cloud tank and lighting effects, a crazed member of an archaeological expedition in Mexico stumbles back to camp muttering about some unspeakable horror. The rest of the team retrace his path back to a cave where they find a movie camera dropped beside a dark, apparently very deep pool overlooked by a large statue of an ancient goddess. When the footage in the camera is processed, the rest of team get to see the crazed man and his companion making their way to the cave, where something awful but not clearly seen happens.

This footage, obviously influenced by the observation camera inside the Quatermass rocket, has a couple of very interesting characteristics. For perhaps the first time a feature film utilized artless, hand-held shaky-cam footage to give an impression of “realism” – here is the root of all subsequent found-footage horror. It’s interesting that a masterful cinematographer like Bava would dare to do something which mainstream filmmakers avoided at all costs; the aim of cinematography until then was a kind of visual perfection, so deliberately using “defective” camerawork affects the viewer’s interpretation of what is being seen. This device has been done to death in recent years, but back in 1959 it was a radical choice, introducing a kind of documentary spontaneity into a blatantly fantastic context.

As we soon learn, the awful thing in the cave in a primordial blob, a giant single-celled organism reawakened by the nearby volcanic eruption, which was apparently responsible for the disappearance of the Aztec empire centuries before. This blob absorbs living matter (what blob doesn’t?), including of course any handy human. The main blob is destroyed in a gasoline fire, but the head of the expedition takes a sample back to Mexico City, where it inevitably grows out of control, aggravated by the handy reappearance of a comet which emits a particular kind of cosmic radiation to which the blob responds.

Although the blob itself never actually gets loose in the city, the film does end with a fairly large scale bit of havoc as the monster grows and splits into multiple blobs which attack the hero’s house (his wife and child trapped inside) as the military turn up with guns and flamethrowers to battle it. Here, although the miniature work is quite obvious, Bava creates some effective and dramatic moments.

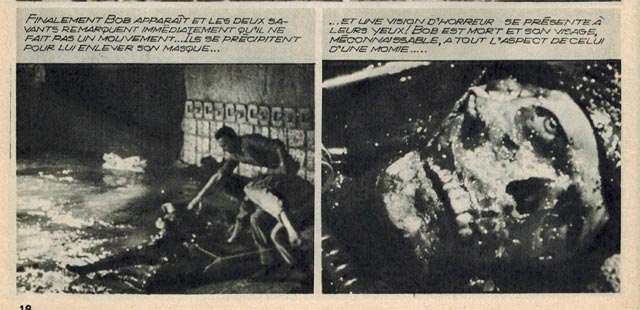

Where the film falls short, as is all too often the case in low budget fantasy and horror movies, is in the script, which spends a lot of time on domestic issues and an underdeveloped conflict involving the hero Professor John Fielding (John Merrivale), his antagonistic wife Ellen (Didi Sullivan) and team member Max Gunther (Gérard Herter), who has designs on Ellen. Max turns out to be the most interesting character as, after being attacked by the monster, leaving his face scarred and one arm stripped of flesh, he goes increasingly mad – here again there are echoes of The Quatermass Xperiment, with a character infected by the alien force and gradually losing his human qualities. Although Max lacks the tragic element which defines Victor Carroon, Herter’s performance has some of the intensity of Richard Wordsworth in the earlier film.

I first saw Caltiki a few years ago on the now out-of-print NoShame DVD, which had a passable but not stellar image (contrast was weak, giving the whole film a greyish tinge); Arrow’s new dual-format edition raises the film’s stature considerably with a 2K transfer from the original camera negative. It’s now possible to see far more detail and to really appreciate those wonderful (if hardly realistic) Bava glass shots. In fact, the disk offers a whole new way to appreciate those effects, because Arrow have included both the 1.66:1 theatrical version as well as a complete open-matte transfer. In the latter, most of the non-effects material is hard matted at the theatrical ratio while Bava’s effects fill the entire 1.33:1 frame, with more detail visible top and bottom.

The disk has two commentaries – the first from the always reliable and informative Tim Lucas, author of the massive Mario Bava: All the Colors of the Dark, the second from Troy Howarth, author of The Haunted World of Mario Bava; obviously there’s some duplication here, but together they supply more information about the production than you ever thought you’d want. There’s a featurette with Kim Newman tracing the film’s links to other blob movies; an archival interview with filmmaker Luigi Cozzi; and a brief introduction and interview with film critic Stefano Della Casa, the latter focusing on co-director Riccardo Freda. The most unusual extra is a PDF of a 54-page French photocomic of the film.

While Caltiki remains a very minor work in the Bava canon, Arrow’s Blu-ray firmly establishes its importance in the director’s development. It bodes well for their continuing commitment to making Bava’s work available in high quality editions.

*

Finally, I’ve just re-watched M. Night Shyamalan’s Split on Blu-ray and it holds up really well to repeat viewing. This is one of his best movies, well-written and beautifully acted. With its success with both audiences and critics, maybe Shyamalan’s other work will finally begin to receive a well-deserved reevaluation.

Comments