Desert noir and 3D from Twilight Time

The 3D boom of the early ’50s actually only lasted a few years. Although it covered almost all genres – from its seemingly natural affinity for horror, fantasy and science fiction to westerns and musicals, adventures, film noir and thrillers – it remained a problematic technology. There were a number of different methods for achieving the effect, but all involved cumbersome cameras and often inefficient projection. And then there were those glasses and the eye strain and the headaches. It’s not surprising that the simultaneous development of widescreen cinematography – the also technically problematic Cinerama, with its three synced cameras for filming and synced projectors for screening, and the more user-friendly CinemaScope and its imitators, which used anamorphic lenses to squeeze more lateral image into a standard frame of negative – quickly pushed 3D out of favour as an inducement to draw TV-besotted audiences back into movie theatres.

Although there were occasional brief revivals of 3D over the ensuing three decades, it remained little more than a novelty or a marketing gimmick, which continued to struggle with those headache-inducing projection issues. I can recall being enormously entertained by Andy Warhol’s Frankenstein, aka Flesh for Frankenstein (dir. Paul Morrissey), when I saw it in 1973, with its brilliantly comic use of depth, even as I suffered severe eyestrain from the experience. Things were a bit better when some of the classics were re-released theatrically during the brief 3D boom in the early ’80s – that’s when I saw Alfred Hitchcock’s Dial M for Murder and Andre de Toth’s House of Wax (I laughed out loud with pleasure in the latter during the scene immediately following the intermission, with the man outside the titular museum whacking two tethered paddle balls at the camera lens. This will no doubt be my next 3D purchase!).

But the format really had to wait for the development of digital technologies to eliminate (or at least ameliorate) the viewing problems. For anyone who’s grown up in the past decade-and-a-half, 3D is a norm. Virtually all animation and almost every blockbuster gets a 3D release, but paradoxically this has shorn the technology of its novelty value; 3D has become mundane, taken for granted … and for many viewers it’s now a bit of a bore, a mere excuse for exhibitors to charge higher ticket prices. Personally, I find that within a few minutes of a movie starting these days, I forget that it’s in 3D. Few filmmakers actually make really creative use of the technique – James Cameron in Avatar did a remarkable job of opening up that film’s world in the space beyond the screen; Paul W.S. Anderson has a similar facility for creating that sense of a deep visual space. But for the most part, 3D is now creatively redundant, something taken for granted as just one more commercial imperative in a business which is, first and foremost, just a business.

But where the digital technology is really paying off, surprisingly, is in the restoration of movies from the first wave, those genre pictures from the early ’50s, which can now be seen without any of the problems which originally plagued the format. As I mentioned several months ago, the high point of the evening my friend Steve and I spent sampling various 3D Blu-rays on his big TV was the scene with the telescope early in Jack Arnold’s It Came From Outer Space. The clarity of the image, combined with both a sense of depth and the poke-in-the-eye effect when the telescope swings towards the viewer embodied what’s most fun about the form; it breaks the barrier of the screen and gives the viewer a sense of interaction with the movie’s world.

*

Inferno (Roy Ward Baker, 1953)

We got that same effect recently when I went over to Steve’s for the evening with my newly acquired Twilight Time Blu-ray of Roy Ward Baker’s Inferno (1953). This is a movie I first saw on TV (in black-and-white) back in the late ’60s or early ’70s and even viewed flat and colourless it stuck in my memory. Or rather, parts of it stuck in my memory (I certainly remembered the moment when a rattlesnake jumps at the protagonist). I was looking forward to seeing it again all these years later, although there’s always that slight hesitation about revisiting something I saw long ago; what impressed my younger self may well turn out to be less than impressive now … and seeing it again might erase a fond memory.

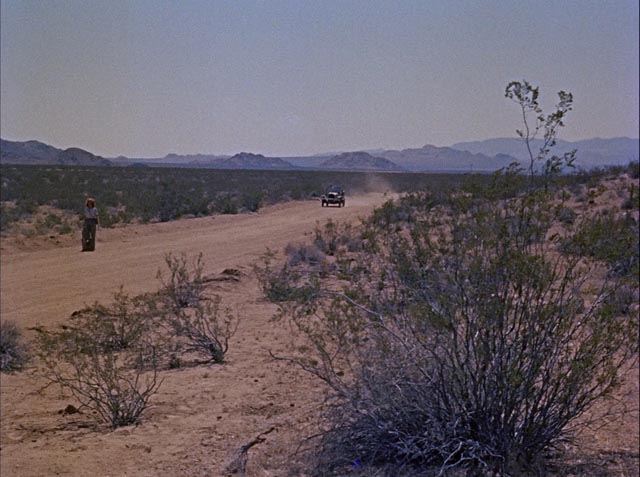

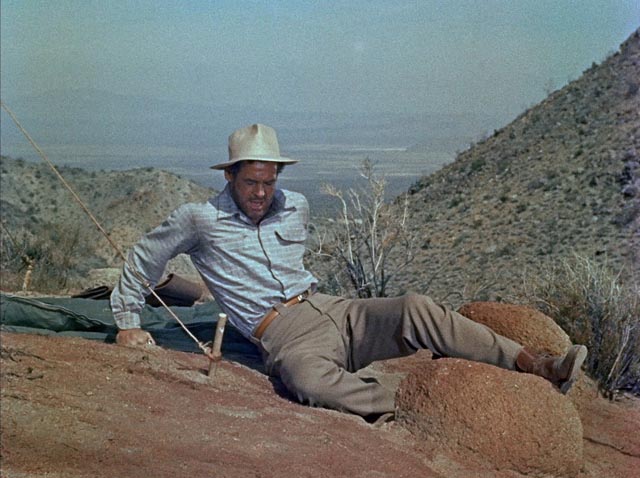

Right from the opening shot, though, this new 3D restoration grabbed us. Baker and his crew (the film was photographed by the great Lucien Ballard) spent much of the shoot on location in the Mojave Desert, taking full advantage of 3D’s potential in a parched landscape which stretches off to a distant horizon. The sense of visual space is breathtaking, the depth of that landscape making the characters in the foreground stand out vividly. Baker and Ballard evoke vertiginous tension with steep ravines and cliff faces, using 3D to emphasize the exhausting distances a man with a broken leg must crawl across as he tries to escape the desert before dying from his injury or a lack of food and water … or from hazards like that snake. The 3D is used with skill and intelligence to heighten the drama of survival.

And thanks to the script by Francis M. Cockrell (whose first credit dates from 1932, and who spent two decades after Inferno mostly writing for television), that drama is tightly plotted and focused on the evolution of an unpleasant character into one who gains sympathy as he acquires self-knowledge through his ordeal.

The film begins, disorientingly, in the middle of the action. A woman, Geraldine Carson (Rhonda Fleming), and a man, Joseph Duncan (William Lundigan), are out in the desert where they appear to be faking an accident with a station wagon pulling a horse trailer. Having abandoned the vehicle, they ride out of the arid wasteland to the place where they rented the horses, asking the proprietor if Geraldine’s husband, Donald Whitley Carson III, has shown up. They claim there was an argument and the businessman has drunkenly abandoned them. With no news of Carson, the pair return to Los Angeles to set in motion a search for the missing man.

But Carson isn’t actually missing. Rather, he’s out there in the mountains at the edge of the desert where he fell from his horse and broke his leg. Geraldine and Duncan had set off ostensibly to get help; but instead they laid a false trail to make it look as if he had crashed the car and become stranded on the far side of the valley. So, a crime of opportunity. The couple have left him to die, with Geraldine holding on to the idea that this isn’t exactly murder, while Duncan is a bit more honest about it.

An interesting note is that we learn that they haven’t actually been lovers before, coming together only on this trip to the desert where both had become fed up with Carson’s unpleasant arrogance and personal abuse. His behaviour on the trip had driven them together and by mutual consent they simply took advantage of the accident to get away from him for good; but with their romance beginning in an act of betrayal and only slightly displaced murder, it’s inevitable that the relationship will become strained … and before long it begins to rot with distrust, leading towards other betrayals.

Inferno divides its time between Geraldine and Duncan’s fraught relationship and Carson’s painful struggle to survive; faced with this physical challenge, which begins with a powerful desire to exact retribution, he gradually sloughs off his anger and bitter emotions. The painstaking process of getting himself down off the mountain, having set and splinted his own broken leg, of carefully rationing his food and water, and seeking sources in the barren landscape as he runs out, forces him to focus on what’s essential. By the time he does make it out, his previous material obsessions have lost their importance; life, rather than money – and revenge – is what matters.

All of this interior process rests on the performance of Robert Ryan, one of the most skillful actors at portraying inner conflicts through physical rather than verbal means – although here, his nuanced physical expression is buttressed by a running voiceover commentary on his situation (in this, the film bears a strong resemblance to Steven Spielberg’s Duel, which is also about a man previously secure in his image of himself who is forced by circumstances to find hidden inner resources in order to survive a physical ordeal).

Ryan is terrific as Carson, beginning as an arrogant asshole and working his way painfully towards a kind of inner peace and empathy for the woman who betrayed him. Baker’s direction and Ballard’s excellent 3D photography provide a vivid and viscerally physical setting within which this inner drama plays out, making Inferno one of the best films to come out of the original 3D boom. The spectacular image quality of the restoration on display on Twilight Time’s Blu-ray puts many of today’s digital 3D movies to shame.

*

Certain structural and thematic aspects of the film – the central triangle involving flawed characters dooming themselves through bad decisions and moral compromise; a bitter marriage leading to betrayal and murder – prompt the question: is there such a thing as daylight noir? Here, with the shadows of streets at night replaced by a vast landscape beneath a searing desert sun, the familiar elements are turned on their head. The wife and her accomplice haven’t schemed murder, but simply take advantage of circumstances which they hope will remove the husband with no effort on their part; the wife is increasingly plagued by guilt, while the man who, according to genre requirements, ought to be her dupe (think Walter Neff caught in Phyllis Dietrichson’s trap in Double Indemnity) becomes more vicious as the original plan begins to fall apart. And the despised husband becomes increasingly sympathetic until, at the end, he has lost all desire for revenge, along with his former love of money. In contrast to a flawed character’s inevitable existential spiral into an unavoidable fate, Inferno traces the upward climb of a flawed character from brute selfishness to personal redemption. So … something like a mirror image of classic noir.

*

There are traces of this “desert noir” in another recent Twilight Time release, a little known Don Siegel film from a transitional period in his career.

Edge of Eternity (Don Siegel, 1959)

As in Inferno, landscape is crucial to Edge of Eternity (1959). And it seems a pity that it was made too late for the 3D craze because it too was shot in impressive natural spaces, in this case in and around the Grand Canyon. But unlike Inferno, Siegel’s film feels as if the story was invented simply to take advantage of the location as a spectacular backdrop, rather than using the landscape as an integral psychological element of the narrative.

In some ways Edge of Eternity is an oddity, a small-scale B-movie shot in widescreen colour by Burnett Guffey, a great cinematographer who was nominated five times for an Oscar (winning twice – once for the black-and-white From Here to Eternity, the second time for Bonnie and Clyde, a hugely influential colour movie). Starring Cornel Wilde, a studio contract actor who never quite became a full-blown star, it was directed by Don Siegel, an efficient, workmanlike filmmaker, at the end of a decade of notable genre movies (Riot in Cell Block 11, Invasion of the Body Snatchers), but ten years away from his biggest commercial successes, which would come when he hooked up with Clint Eastwood, whose stardom Siegel helped to consolidate. And yet, despite these participants, Edge of Eternity is still an unassuming programmer seemingly designed to fill half of a double bill.

Which is not to say that it’s without interest. Although the murder mystery is quite perfunctory, the script pays a lot of attention to the characters, echoing to some degree two movies made several years earlier: John Sturges’ Bad Day at Black Rock and Richard Fleischer’s Violent Saturday (both 1955), both of which, like Edge of Eternity, mix crime with smalltown melodrama in a desert setting.

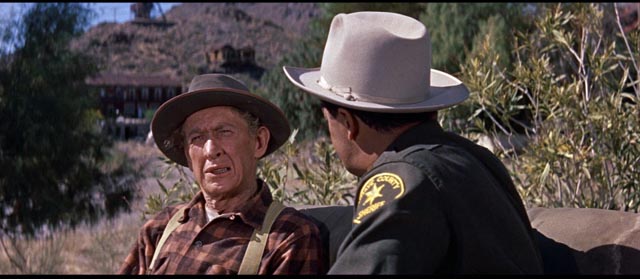

Siegel’s film (again like Inferno) opens in mid-action: a man parks his car at the edge of the Canyon and gets out to scan something in the landscape with a pair of binoculars. Another man sneaks into view, releases the car’s brake, and tries to run the first man off the rim. The car crashes into the Canyon and the two men struggle, with the would-be murderer falling to his death. We have no idea who these men are, nor what might be the focus of the first man’s attention.

It’s only after this very dramatic prologue that we meet the film’s protagonist, Deputy Les Martin (Wilde), who immediately makes what turns out to be an error of judgment. Stopped by an excitable old man, Eli Jones (Tom Fadden), who tells him of finding a distraught man stumbling around the Canyon edge (who, of course, is the would-be murder victim), Martin ignores him and takes off after a car which speeds past on the precarious road. It turns out that this is being driven by Janice Kendon (Virginia Shaw), daughter of Jim Kendon (Alexander Lockwood), the owner of a local gold mine which was closed down after the war. Giving her a speeding ticket is a kind of meet-cute, suggesting that a romance is in the offing.

But before the romance can get going, the man Eli was trying to tell Martin about turns up dead, brutally murdered. This hangs over Martin for the rest of the film, a tragic mistake which reflects back on his prior history as a Los Angeles detective who had made another fatal mistake while struggling with the illness and death of his wife. Martin is a flawed character, yet good at his job. The sheriff (Edgar Buchanan) who hired him has faith in him, but knows that if the case isn’t resolved quickly, he’ll have to sacrifice the deputy to political expediency – particularly as the county attorney wants to use him as a device to get reelected.

The film divides its time between the vast Canyon and the small, almost deserted town at its edge. The cast is small, not leaving a lot of room for red herrings. Martin becomes involved with Janice, even as he casts suspicion on her father and deals with her angry, alcoholic brother Bob (Rian Garrick). In off hours he hangs out at the bar run by big, affable Scotty O’Brien (Mickey Shaughnessy), who complains about being trapped in this nowhere town and dreams of escaping, at least temporarily, to Las Vegas.

Although Martin’s suspicions that someone is stealing ore from the closed mine is ultimately borne out, the resolution to the mystery is almost tossed away – and feels as if it could have been revealed at any time without having any adverse impact on the story, which is focused on the characters and their troubled relationships rather than the murders themselves. And all of this really only exists in order to lead us to the final act which involves an exciting desert chase which leads to some really spectacular aerial sequences with a helicopter flying in the Canyon and a climax involving a mining cable car strung between the cliffs hundreds of feet above the Canyon floor. The stunt work here is pretty hair-raising; even though the closer shots with the actors are done with rear projection, there are plenty of wider shots made on location with stuntmen fighting and hanging from the cable car while the helicopter hovers nearby.

Once again, the noirish elements – particularly the flawed hero haunted by past and present mistakes – ultimately dissolves in the light of the desert sun, with a resolution in which the bad guys pay the price and the hero gets the girl. So perhaps the moral ambiguities of noir really do depend on visual darkness at least as much as particular narrative structures.

*

Both Inferno and Edge of Eternity belong to the tail end of the studio system, when individual stories didn’t need to be “big” or “important”; they just needed to be well-crafted by filmmakers who knew their job and how to take advantage of the resources available to them. They’re both small films, but they provide effective and satisfying entertainment. And both have been given good presentations by Twilight Time, although the image quality of Edge of Eternity isn’t quite on a par with Inferno.

Each disk comes with a commentary – film historian Alan K. Rode with Robert Ryan’s daughter Lisa Ryan on Inferno, Nick Redman and C. Courtney Joyner on Edge of Eternity – and there’s a brief featurette about the use of 3D in Inferno.

Comments