Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979): Criterion Blu-ray review

In more than five decades of movie watching, Andrei Tarkovsky stands out for me from all other directors. This is something I have pondered quite a lot since I first encountered his work on a trip to England in 1975. I knew nothing about him, but noted a screening of Solaris (1972), a film based on one of my favourite novels at the time. Although in later years, I saw that this film was not his best work, I was overwhelmed by it on that first viewing. It represented my first experience of something which would take me some time to become consciously aware of – the difference in film (and life for that matter) between time and duration. And by that I mean, the difference between time as externally measured (say, the 166-minute running time of Solaris) and one’s subjective experience of that time, which is dependent on one’s sense of engagement. Tarkovsky’s work often elicits complaints about being slow and ponderous, but for me the strange, unfamiliar, drawn-out rhythms of Solaris woke something which has been with me ever since: the desire and ability to give myself over to a filmmaker, to become immersed in the experience of a film rather than simply watch it passively. And in that state of mind the objective running time becomes irrelevant; one is in the moment, with little or no sense of time passing.

This process began part way through Solaris, after Kris Kelvin leaves his father’s dacha and drives back to the city. That journey, viewed from a moving car, passing through tunnels and over flyovers, as the idyllic countryside of the opening gives way to the dense and unnatural architecture of the city, becomes not simply an easy metaphor for the journey through space (at the end of it Kris arrives at the research station floating above the sentient ocean which covers the planet Solaris) – in a sense, it is Tarkovsky’s way of reaching into the viewer’s head and adjusting the speed at which we perceive and think. He is slowing our perception so that we are ready to absorb the images and ideas which will come into play once we reach Solaris. This is – I hesitate to use the word “technique” because that gives it a rather clinical tone – a psychological use of editing which draws the viewer towards something like a waking dream state. It’s something he uses again, to even more potent effect, in his greatest film, Stalker (1979).

All other effects in Tarkovsky’s work – psychological, emotional, aesthetic – are rooted in his masterful control of pace and duration. In a way that few other filmmakers have mastered, Tarkovsky prompts us to see the world as not merely a physical environment but rather as imbued with a living presence. This is deeper and more profound than a simple expression of some kind of religious belief, although his films do contain a great deal of Christian iconography. Tarkovsky’s evocation of the natural world suggests Animism; his imagery has a remarkably dense and tactile quality, a material presence, which nonetheless seems permeated with a spiritual energy. It would not be exaggerated to say that Tarkovsky’s films taught me to see the natural world in a way I had never seen it before. I can even pinpoint the moment in which he “opened my eyes”: the shot in Mirror with the Mother sitting on the wooden fence, looking down across the meadow as a wind suddenly sweeps over the long grass, animating the landscape. This woke me to the fact that the rest of the film is filled with elemental imagery – wind, earth, fire, water – and the lives of the characters exist within a matrix of energy which makes the human elements of history which are depicted (on a grand scale, the Spanish Civil War, World War Two, Stalinism; and on a personal scale, the death of a parent, the disintegration of a marriage) seem painful but nonetheless transitory, errors which have been caused by our own limitations.

Even at their most intimate, Tarkovsky’s films possess a breadth and ambition which give them an impressive sense of scale, whether he is recreating an entire Medieval world (Andrei Rublev) or a single life (Ivan’s Childhood, Mirror). That scale is connected to an allegorical quality which runs through all his work, a quality however which is not reducible to simple meanings, but rather expresses both a quest for and construction of personal meaning, a desire to discover the connection between individual experience and a universe which remains suggestive but ultimately not fully knowable. On the human scale, Tarkovsky’s work revolves around an inner conflict between hope and destructiveness, the ways in which human beings have a tendency to defeat their own deepest desires … and the ways in which the spiritual underpinnings of the world sometimes protect us from our own worst tendencies.

At its most superficial, Stalker (adapted by Boris and Arkady Strugatsky from their science fiction novel Roadside Picnic) can be read as a metaphor for the constraints imposed by the Soviet Union on individual freedom. In the opening section, we see a grim, colourless, polluted landscape populated by people whose energy has been suppressed by a system which denies those spiritual energies which give life meaning beyond the basest material existence. The title character, known only as the Stalker (Alexander Kaindanovsky), is a misfit, a former convict living in a decaying apartment with his wife and crippled daughter. He is driven by a deep compulsion related to a region called the Zone, a mysterious place which has been sealed off by the government after being devastated by an unknown catastrophe. (In the book, it is more clearly the result of an alien visitation which has left it contaminated and unstable; in the film, it is a haunting premonition of the deserted landscape surrounding Chernobyl.) The Stalker has a vocation to guide others across the heavily guarded, militarized boundary between the world and the Zone, to lead them to a special place which is reputed to grant a person’s deepest wish. The government’s restriction of access is a denial of the possibility of the individual’s self-realization.

The Stalker meets his two latest clients in a gloomy bar: the Writer (Anatoly Solonitsyn, who had previously appeared in Andrei Rublev, Solaris and Mirror) and the Professor (Nikolai Grinko, also previously in Andrei Rublev, Solaris and Mirror, as well as Tarkovsky’s first feature, Ivan’s Childhood). While these identities imply archetypes rather than characters, each actor gives an intensely personal, idiosyncratic performance, imbuing the film with richly layered dramatic life. The two clients both seem disillusioned, and in the case of the Writer deeply cynical, and the Stalker struggles to instill in them some of his own sense of mystery. In fact, as the film progresses, its increasingly deepening sense of mystery comes entirely from him. This is one of the strangest things about the film; although ultimately we see nothing really strange or inexplicable, we nonetheless feel the mystery and danger of the Zone because the Stalker has infected us with his own sense of awe.

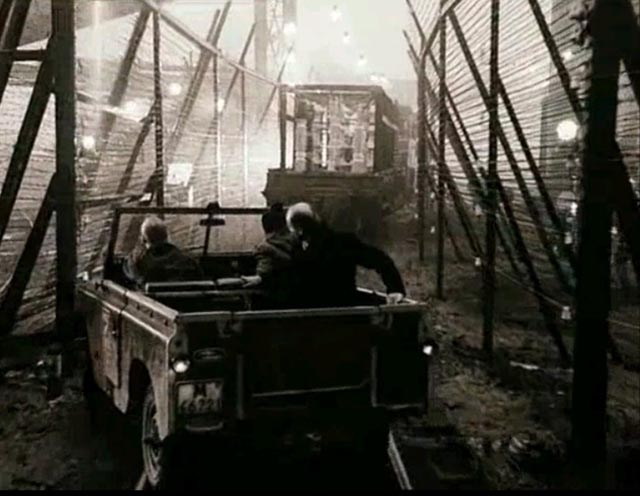

The entry into the Zone is one of Tarkovsky’s most powerful yet puzzling sequences. The trio drive in a Jeep through a maze of littered streets and ruined buildings, occasionally forced to hide from uniformed patrols, and finally passing through a barbed wire barrier along tracks in the wake of a train pulling a load of heavy electrical equipment. Guards fire after the Jeep with machine guns, but don’t actually follow the three into the forbidden area. Objectively, the geography of this sequence makes little sense; but subjectively it reflects the characters’ state of being trapped by an implacable system determined to erase their individual identities. Visually, there are unavoidable echoes of the Gulag, with an implication that these three are breaking free, escaping from the oppressive control of the government.

And here we get to that quintessential Tarkovskian sequence, a more richly conceived and realized echo of that drive into the city in Solaris – the journey by motorized railcar into the Zone. For four minutes, the camera focuses intensely on the heads of the three men, often the back of the head, occasionally turning into profile, while we hear the hypnotic rhythm of the metal wheels on the rails, with the bleak, out-of-focus industrial background gradually giving way to a more open space with trees and meadows – still all in a lifeless, desaturated sepia palette. The rhythmic sound also subtly evolves, the clatter of the wheels taking on an increasingly ethereal quality as it is first echoed by electronic instrumentation and then replaced – not exactly by music, but rather a soundscape suggesting a shift in the materiality of the world. This is the most fully realized instance in Tarkovsky’s work of the effect I previously mentioned, its rhythms, both visual and auditory, working on the viewer in a subtle, almost subconscious way, in effect slowing down the watching brain to heighten perceptivity. And then abruptly, the image cuts to lush colour as the car rolls to a stop in a dense landscape of trees and long grass. We have been brought to a waking dreamstate in a place which is both intensely, physically present and yet strangely abstract and malleable.

The Stalker seems to feel that he has returned to his natural environment, briefly wandering off with warnings to the others to stay where they are. This is the place he feels most alive and we sense that, although his role is to guide others, he feels a certain resentment at their intrusion, or more specifically at their limited understanding and deficient respect for this mysterious place. He has to warn them repeatedly about the dangers that surround them, about the instability of the place and the risk of being lost forever if they wander in the wrong direction. While the film’s opening section has taken place in a constructed maze, here the maze is conceptual, defined by the Stalker’s knowledge rather than by obvious physical barriers.

Their destination is visible just a few hundred yards away – a ruined building in an open field – but the Stalker assures the others that there is danger in trying to take a direct route. The writer scoffs and sets off towards the building, but as he draws close a voice tells him to stop and go back. He returns and asks why the Stalker called out … but it wasn’t the Stalker. The Professor suggests that it was the Writer himself, providing an excuse for his own failure of will.

The ensuing journey to the building, with its mysterious inner Room, takes the three men in a circuitous way through this waterlogged landscape, past overgrown and rusting tanks, collapsed ruins and tunnels and rushing water. At one point, the Professor, having left his backpack, insists that he must go back to get it. The Stalker warns that going back is impossible, that he’ll be irrevocably lost, but he goes anyway. The Stalker and the Writer continue on through a watery, litter-strewn drain and when they finally emerge, they find the Professor sitting by a small fire eating from a can, somehow having gotten ahead of them. Although nothing much seems to have happened, Tarkovsky has conveyed a sense that here time and space are unstable, malleable, collapsing in on themselves.

As they travel, the three reveal something of themselves and their motives; they circle around issues of science, art and religion, revealing deep-seated insecurities, with only the Stalker possessed of any kind of certainty – but that certainty is about something invisible, immaterial, impossible to prove empirically. These discussions build to the lengthy sequence in which the trio finally reach the antechamber to the Room at the heart of the Zone. Here the Stalker reveals that no one he has brought here has ever actually crossed the threshold. As the Writer and the Professor conclude, in the end it’s impossible to know what one’s own deepest wish really is and perhaps the risk of attaining it is too great. But the journey itself has brought them something – a degree of self-knowledge about what is missing from their lives. The Zone has worked on them to a degree which makes entering the Room no longer important.

At this point, we get one of those powerful, mysterious images which are characteristic of Tarkovsky’s films, an image whose meaning is not thematically specific yet suggests something which each viewer must interpret for him- or herself: the camera is inside the Room, looking back through the doorway to the three men. As the Stalker comments that it’s so peaceful, and wonders whether he should bring his wife and child to live here – “forever” – where no-one can harm them, the camera slowly tracks back deeper into the room, light and colour shifting strangely, and it begins to rain. These elemental shots occur throughout Tarkovsky’s work, reinforcing that sense of a living energy beneath the material surface of the world, an energy whose meaning and purpose remain beyond our understanding, but which ultimately suggests something hopeful. The room itself seems sentient, patiently watching these men coming to terms with their place in the world.

That feeling is reinforced in the film’s epilogue. We don’t see the men return to the world, but find them once more in the bar, the image again sepia-toned. It’s almost as if they had never actually gone on their journey, the only indication that it all happened being the presence of the black dog which they encountered in the Zone, which is now sitting near their table in the bar. The Stalker’s wife (Alisa Freindlikh) arrives to fetch him, and the family walk away beside a polluted river, the Stalker carrying his daughter, Monkey (Natasha Abramova), on his shoulders. Cutting to a close profile of the girl, seemingly floating against the landscape, the image returns briefly to colour, imbuing her with some of the energy of the Zone. In the final shot, with the silent, crippled girl back at home sitting by a table with a couple of glasses on it, and the sound of a passing train in the background, we see one of the glasses begin to move by itself, sliding across the table as the girl tilts her head and looks at it. This suggestion of telekinesis, something passed on to her along with her physical disabilities as a result of her father having been contaminated by the Zone, a complex mutation which is physically damaging even as it produces a new mental power, ends the film with an epiphany, which again is open to the viewer’s own interpretation.

*

The story of Stalker’s troubled production is well-known, yet the film itself seems to bear no marks of the enormous problems which plagued it. Originally set to shoot in a Central Asian desert, an earthquake forced the production’s relocation to Estonia. It is impossible to imagine what it might have been if shot in an arid landscape, as the wet, verdant imagery of the Zone and the bleak polluted landscape of the world outside it are so integral to the film as we now have it. And then, after shooting more than half of the film, a lab error destroyed most of the footage and production had to be halted, giving Tarkovsky time to rethink everything as a new budget was worked out. By all accounts the biggest change at this stage was the transformation of the Stalker from something of a cynical charlatan to the holy fool we now see. Again, what kind of film would have resulted without the lab disaster is hard to imagine. Stalker as it exists is so perfectly realized that its form seems inevitable. As Tarkovsky’s greatest work, it stands as one of the greatest achievements of cinema, a work of art which could only exist on film, using every potential of the medium to create something which seems to grow and change with every viewing, impossible to reduce to any single fixed interpretation, while providing an experience which mysteriously expands the viewer’s ability to perceive not only cinema but the world itself.

*

The disk

Criterion’s Blu-ray of Tarkovsky’s masterpiece uses a 2K restoration by Mosfilm from the original 35mm negative, and the image is stunning in the richness of its colours (in the Zone) and the clarity of its details throughout. This far surpasses any previous home video version. The mono sound, from original 35mm magnetic tracks, is equally subtle and detailed.

The supplements

There are three archival interviews, sourced from the RUSCICO DVD released in 2000: set designer Rashit Safiulin (14:24), composer Eduard Artemyev (21:10), and cinematographer Alexander Knyazhinsky (5:45) all speak about their working relationship with the sometimes difficult Tarkovsky.

The one new supplement is an interview with Geoff Dyer (29:11), author of a book about the film (Zona: A Book About a Film About a Journey to a Room), in which he discusses the production itself as well as his own shifting relationship with the film.

The booklet essay is by Mark LeFanu, author of one of the first books about Tarkovsky in English, The Cinema of Andrei Tarkovsky (BFI, 1987).

The technical quality of the disk, combined with the beauty and power of the film itself, guarantees that this will be one the finest and most important releases of the year.

Comments

This is a wonderful essay, thank you. I watched the film yesterday and I love how Tarkovsky clearly leaves ample room for multiple, endless interpretations by the viewer. One thing I found interesting is how, throughout the film, perhaps right up until the Professor’s gambit on the cusp of the room, I kept trying to project Western/American expectations on the movie. Tarkovsky deliberately and correctly has no intention of putting surprises or great resolutions or gotcha moments in the film, which I suspect I will be thinking about for a long time. Thank you again for your review.

Thanks for your feedback. This is definitely one of those rare films which gets under your skin and somehow becomes a permanent part of you.

Love this review. Very insightful and eloquent. You picked up on many things which I missed. I wish my review was as good as yours!