Recent deaths: Tobe Hooper and others

On August 26, Tobe Hooper died. He was 74. His breakthrough movie, made before he was thirty, is one of the most influential horror movies ever made. Despite its early reputation as one of the goriest movies ever made, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is actually not particularly graphic. There’s barely any blood at all – but Hooper used his camera skillfully to suggest that the audience was seeing unimaginable horrors. It’s a film of deeply perverse atmospheres and at times outrageous humour. One of the reasons it remained banned in England for years is that there were few overt moments of graphic violence that could be cut out to make it more “acceptable”; the uneasiness which disturbs audiences permeates every moment.

Gaining success at the start of a career can be a mixed blessing and in Hooper’s case the shadow of Chain Saw became a kind of burden. Everything that followed was inevitably measured against it and for many the subsequent movies were found wanting. He had a lot of trouble with producers, finding himself replaced on a number of projects. His biggest mainstream movie, Poltergeist, was produced by Steven Spielberg and many people unkindly chose to believe that Spielberg himself actually directed it. Ironically, despite that movie’s commercial success, it’s not one of Hooper’s most interesting – perhaps for the very reason that Spielberg had too much influence.

Also ironically, Hooper’s best work was often criticized for its strange tone, a subversive, disconcerting mix of horror and humour which confounded genre expectations. Audiences and critics didn’t know what to make of his follow-up to Chain Saw, but although Eaten Alive is more stylized, shot entirely on studio sets rather than actual locations, it represents the comic horror of the dinner scene in the former blown up to fill an entire movie. Eaten Alive is suffused with a madness which seems to fill Hooper with enthusiastic glee. Far from being a misfire, it shows the filmmaker exploring the limits of his art in pursuit of the darkness lurking inside his characters. William Finley and Neville Brand are unsettling and nightmarishly entertaining in ways which have nothing to do with the conventions of mainstream naturalism, yet both are disturbingly plausible as human monsters viewed through a darkly comic lens.

Hooper brought the same kind of theatrical exaggeration to much of his work and it always seemed to elicit a confused response, and after his rocky three picture deal with Cannon, he was mostly stuck with second-rate material and inadequate budgets. But that Cannon deal gave him both his biggest budget and his greatest film – the still-underrated Lifeforce, a deranged mix of sci-fi and horror which allowed Hooper full freedom to explore his fascination with human derangement. Those who criticize the film’s performances as bad acting need to take another look; this is as stylized as kabuki, human psychology and behaviour rendered through almost ritualized physical and vocal gestures. Not to mention that the film has a rousingly apocalyptic third act. Here we can see Hooper’s real strength as a filmmaker, a willingness to pursue without hesitation where his material leads. At his best, he simply doesn’t hold back, he’s unafraid to step beyond conventional expectations … a strength which unfortunately made him a poor fit for the limited imagination of the mainstream.

*

There have been a number of other notable deaths recently.

Jeanne Moreau on July 31 at age 89. Her presence was important to the nouvelle vague, with roles in films by Louis Malle (Elevator to the Gallows, The Lovers) and Francois Truffaut (Jules et Jim, The Bride Wore Black), but her presence extended far beyond that movement – she was in Roger Vadim’s Les liaisons dangereuses, Michelangelo Antonioni’s La Notte, Joseph Losey’s Eva and Mr. Klein, Bunuel’s Diary of a Chambermaid, Bertrand Blier’s Going Places, and multiple movies for Orson Welles (The Trial, Chimes at Midnight, The Immortal Story, The Deep). Her career spanned six-and-a-half decades and encompassed small auteur works like Marguerite Duras’ Nathalie Granger and huge international productions like John Frankenheimer’s The Train, but I have to admit that, although her talent was undeniable, she was seldom an actress I warmed to. There was something a little opaque about her which seemed to keep her characters at a slight distance from the audience … which is perhaps why one of the roles I most appreciate is her sexually repressed and murderous schoolteacher in Tony Richardson’s Mademoiselle (with a script by Duras based on a story by Jean Genet); here her persona meshes perfectly with the character to chilling effect.

*

John Heard, who died on July 21 at age 71, had a remarkably prolific and varied career in film and television, but as most obituaries put it he was “best known as the dad in Home Alone”, a rather sad epitaph for a very talented actor whose chief “fault” was perhaps that he disappeared so completely into his roles as to be almost invisible. Until this year, I was most likely to associate him with the rather stolid “hero” of Paul Schrader’s Cat People, a character of almost overstated ordinariness who is finally revealed as rather creepily perverse as he’s drawn into a sexual relationship with Nastassja Kinski’s cursed Irena which takes on S&M overtones. He also starred in Douglas Cheek’s seedily entertaining ’80s horror C.H.U.D. (which as we all know stands for Cannibalistic Humanoid Underground Dwellers). But it was only a few months ago that I finally saw perhaps his greatest performance as the physically, psychologically and emotionally crippled Vietnam vet Alex in Ivan Passer’s Cutter’s Way, a performance so harrowing that it may have made some filmmakers shy away from casting him in lead roles.

*

Jerry Lewis died on August 20, aged 91, having continued to work until last year after debuting in movies in 1949. He was a big part of my childhood and adolescence as I watched many of his movies on TV in the ’60s and early ’70s, but at some point his exaggerated persona as a goofy klutz stopped seeming funny to me. By an odd coincidence, just a month ago I watched my favourite Martin Scorsese film again which also happens to feature one of Lewis’ greatest performances: in The King of Comedy he stars as talkshow host/comedian Jerry Langford who is stalked by obsessed fan Rupert Pupkin (Robert De Niro is his greatest performance). Lewis plays the darker side of celebrity with convincing skill, and yet manages to evoke a degree of sympathy for Langford, a man trapped by his own fame and popularity. Two years ago I revisited what many consider Lewis’ best work as a filmmaker, The Nutty Professor, which is most interesting as a rumination on the same theme, dissecting the persona he had created as a performer and finding it rather disturbingly repulsive. No doubt he left very clear instructions for the treatment of his legacy, but perhaps someone will now leak out a copy of his long-suppressed Holocaust movie The Day the Clown Cried.

*

Haruo Nakajima died on August 8 at age 88. Although he got his start in movies as a supporting player in samurai and war films (including parts in films by Akira Kurosawa and Ishiro Honda), Nakajima ascended to the movie pantheon with his work in a big rubber suit in Honda’s original Gojira. This he followed up with multiple appearances in the kaiju movies which came in the Big G’s wake – Rodan, Moguera in The Mysterians, Mothra (the larva), Magma in Gorath, Baragon in Frankenstein Conquers the World, King Kong in King Kong Escapes … and on and on. He set the standard for kaiju suit acting, stomping villages and cities into the ground and engaging in giant monster wrestling matches which thrilled many a kid at Saturday matinees.

*

Joseph Bologna, who died on August 13 at age 82, had a long career in movies and television, most often in supporting roles, but also as an occasional writer and director. I remember him best for his lead role in James Frawley’s underrated disaster film parody The Big Bus, which may have been a bit ahead of its time. Made seven years before Airplane!, in the middle of the 70s disaster boom, it doesn’t push its jokes as hard and fast as Jim Abrahams and the Zucker Brothers, which perhaps makes it less overtly funny, but this lower key mockery of genre conventions actually makes it a better movie.

*

Robert Hardy was another actor with a long and prolific career, mostly on English television. He played a lot of military types and politicians (frequently Winston Churchill), but is now no doubt best known as Cornelius Fudge in the Harry Potter movies. But for me his key role was as country vet Siegfried Farnon in the long-running All Creatures Great and Small series based on James Herriot’s autobiographical accounts of being a vet in the picturesque Yorkshire Dales in the 1940s. Hardy played Herriot’s irascible senior partner in the practice. Steeped in nostalgia and sentiment, the series had enormous charm and Hardy supplied a great deal of its appeal.

*

Playwright and actor Sam Shepard died on July 27, aged 73. Alongside a successful career writing for the theatre, Shepard appeared in a dizzying variety of movies, lending his lowkey, easy-going persona not only to serious works like Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven, Philip Kaufman’s The Right Stuff and Jeff Nichols’ Mud, but also to disposable genre projects like Dominic Sena’s Swordfish, Daniel Espinosa’s Safe House and the Nicholas Sparks adaptation The Notebook. Quite a few of his plays were adapted to film, and he also wrote some original works for the screen, including contributions to the script for Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point, Bob Dylan’s Renaldo and Clara, and Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas.

*

And finally, although only tangentially connected to movies – British author Brian W. Aldiss died on August 19, aged 92. Aldiss was one of the first science fiction authors I ever read and his novel Hothouse was a favourite of mine for years, along with Non-Stop (whose U.S. title, Starship, gives away the book’s big reveal). He was also one of the first writers who introduced me to experimental fiction with Report on Probability A, which I read as an adolescent, and Barefoot in the Head, a science fiction novel disguised by Joycean wordplay, set in a world after a war waged with psychedelic drugs, which I confess I could never get through. His autobiographical trilogy A Hand-Reared Boy, A Soldier Erect and A Rude Awakening were a kind of precursor in my reading to J.G. Ballard’s brilliant Empire of the Sun as an account of coming of age before and during World War Two – with the added element of a surprisingly frank treatment of adolescent sexuality. His history of science fiction Billion Year Spree was probably my first exposure to literary history and criticism, tracing the genre back to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, whose influence he openly acknowledged in his novel Frankenstein Unbound, which Roger Corman adapted in 1990 as his final film as a director. Aldiss’ short story “Supertoys Last All Summer Long” was the basis for Spielberg’s A.I., while Keith Fulton and Louis Pepe adapted his illustrated short novel about conjoined twin rock stars, Brothers of the Head, in 2005. (After working on David Lynch’s Dune, I sent Lynch a copy of the latter book because I was struck by certain similarities to his script for Ronnie Rocket … though I don’t know if he ever read it.)

*

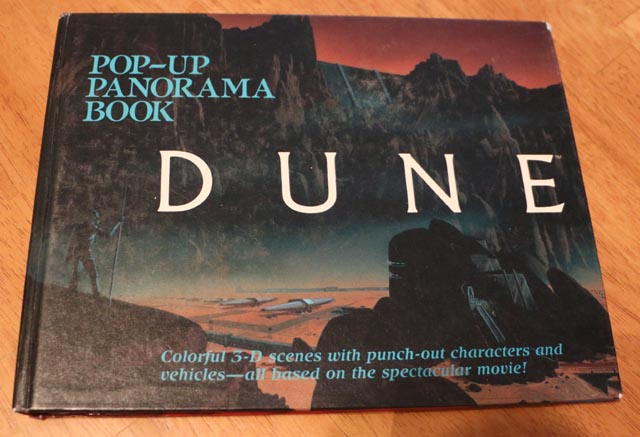

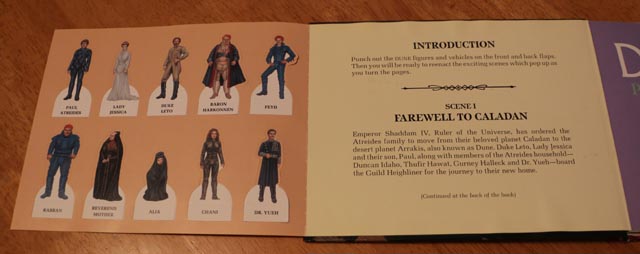

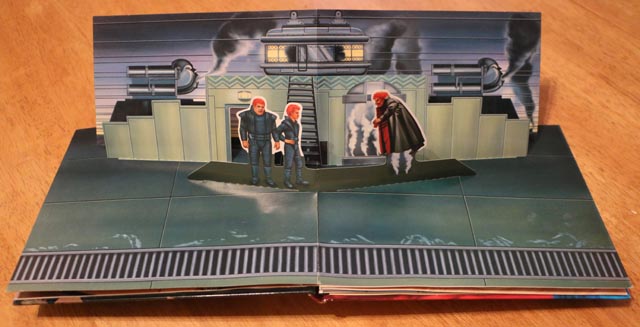

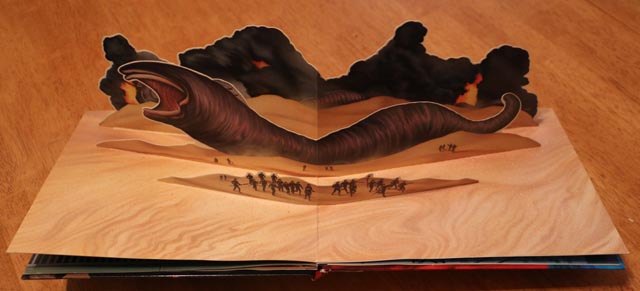

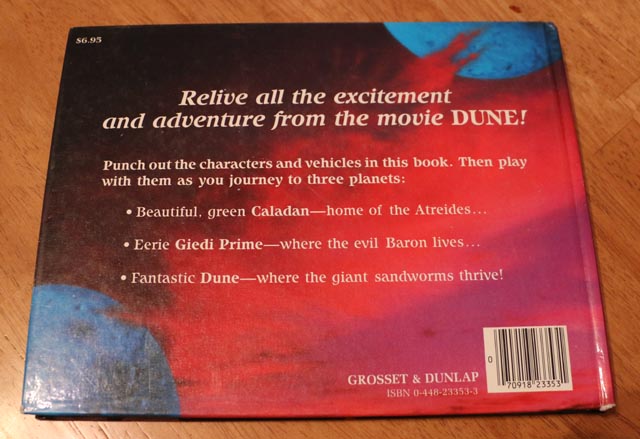

On a lighter note … speaking of Dune, a friend well aware of my connection with the movie recently gave me a copy of one of the odd tie-ins which were produced when it was hoped that Lynch’s adaptation would be a Star Wars-like success. This is a Grosset & Dunlap pop-up book based on the film, which like the Dune colouring book bizarrely suggests that someone in the De Laurentiis and Universal marketing departments assumed that this dark, dense, perverse epic would appeal to kids!

Comments

Lifeforce continues to be one of my favs, I wish I liked more of his work. I haven’t seen most of his TV work but I have seen several of his features. Most of the old ones I didn’t bother upgrading from VHS to DVD and no longer have copies. Lifeforce I had a VHS, a Laserdisc, a DVD and now a Blu-ray. Hope they don’t have any more friggin’ formats before I die.

Lifeforce was Hooper’s peak. His Invaders From Mars remake was a huge mistake, but Chainsaw 2 has its good points (I just re-watched it the other day); more than any of his other movies, it pushes horror deep into comedy. Of the stuff I’ve seen post-’86, there seems to be nothing that reflects his strengths – Spontaneous Combustion, The Mangler, the Toolbox Murders remake all seem to be marking time. I also recently re-watched his TV version of Salem’s Lot and, despite the limitations of network TV, it actually holds up quite well thanks to a good cast and some interesting camera technique. But if you look back over his filmography, it’s kind of sad that someone with a 4+ decade career and very obvious talent only managed to create a handful of really memorable movies – and some of those are not entirely successful. If you haven’t seen them recently, I’d recommend taking another look at Eaten Alive, The Funhouse and Chainsaw 2.