Summer viewing: science fiction

One of my earliest memories of reading is a Penguin paperback of H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds. I was about eight years old – which seems rather precocious – but I distinctly recall being enthralled by the image of those three-legged Martian war machines striding across the English countryside. For years, science fiction and fantasy made up the majority of my reading and, with Doctor Who debuting on the BBC three weeks after I turned nine, I was also hooked on SF movies and TV shows. Although my reading in the genre had declined by the time I was twenty, I never lost my taste for the movies. In this respect, 1968 was a critical year, with the almost simultaneous release of 2001: A Space Odyssey and Planet of the Apes when I was thirteen.

These movies represented two different strains of the genre. Kubrick’s, for all its mysticism, clearly evolved from the “hard science” of George Pal’s Destination Moon (1950), When Worlds Collide (1951) and Conquest of Space (1955), while Franklin Schaffner’s Planet of the Apes mixed adventure with satire, its space flight trappings serving as a device to reach the Apes’ alternate reality, more akin to Pal’s The Time Machine (1960) than the earlier movies. But despite their differences, they both illustrated the genre’s penchant for using fantastic concepts to comment on contemporary issues and aspects of social and political behaviour. Elements of the Cold War linger in Kubrick’s future, while then current conflicts between a conservative, war-mongering establishment and a more hopeful, rebellious generation are key to events in Schaffner’s alternate world.

The influence of 2001 can be discerned in subsequent movies like Silent Running (1972), Demon Seed (1977), even Alien (1979), while there are traces of Apes in Logan’s Run (1976), Star Wars (1977) and even Avatar (2009). But there were other SF movies in the ’60s, largely overshadowed by the two big ones. Just the previous year, Hammer released the third of their features adapted from Nigel Kneale’s ’50s television serials about the rocket scientist Bernard Quatermass. Quatermass and the Pit (1967, Five Million Years to Earth in the U.S.) has some interesting parallels with 2001: it begins with the unearthing of an alien artifact which becomes reactivated by human contact, unleashing powerful forces which turn out to have been integral to our species’ evolution. While Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke hint that there is something purposeful and positive in this influence, they also propose that there is an inherently violent element in the development of human intelligence. This point is key to Quatermass and the Pit, where it is revealed that we were moulded in the image of a rigidly hierarchical race from Mars which managed to destroy itself through religious and ethnic intolerance.

*

Robinson Crusoe on Mars (Byron Haskin, 1964)

The Red Planet is, as the title indicates, crucial to Byron Haskin’s Robinson Crusoe on Mars, made three years earlier. I just re-watched this on Criterion’s Blu-ray and have to admit that, although it remains an old favourite, it looks a lot creakier now than when I first saw it on TV several decades ago (and on laserdisk in the late ’90s and again on DVD in the early 2000s). But even though it wasn’t a success when first released, it has influenced a number of subsequent movies, not least Ridley Scott’s The Martian (2015) and Anthony Hoffman’s Red Planet (2000), both of which deal with astronauts stranded on our neighbouring planet. Like The Martian, Haskin’s movie has its protagonist, Commander Kit Draper (Paul Mantee), spend most of his time figuring out how to survive – finding enough breathable atmosphere, drinkable water and food. Of course, since 1964 we’ve learned a lot more about Mars, so the older film’s environment is more obviously implausible to a modern viewer.

And then, for dramatic purposes (and to justify the title) halfway through Draper meets an alien slave whom he immediately dubs Friday (Vic Lundin). Apart from shifting the movie more obviously towards outright fantasy – Friday has escaped from his alien overlords who come to Mars to mine for unidentified minerals (arriving in re-purposed models from Haskin’s War of the Worlds [1953]), and the pair set off on a long trek through vast underground caverns to the polar icecap – this twist introduces some very problematic attitudes, with Draper reiterating the condescending superiority of European colonialism towards this subservient “other”. He might not repeat the brutality of the aliens, but he assumes the same right of dominance over Friday, who is deliberately made to resemble some kind of South American Indian.

The strongest element of Robinson Crusoe on Mars is the attention it pays to Draper’s ingenuity in figuring out how to prolong his life until (hopefully) some kind of rescue expedition can be mounted. Less successful are many of the technical details (for instance, Mars’ atmosphere is low in oxygen, yet the planet’s surface is a Hellscape of flames and exploding fireballs). But it still represents a sincere attempt to treat the genre relatively seriously.

The disk includes the group commentary from Criterion’s original laserdisk edition (which I have still have in a box along with other laserdisks at the back of a closet). This was pieced together from separate recording sessions with stars Paul Mantee and Vic Lundin, production designer Al Nozaki, special effects artist and film historian Robert Skotak, and (most importantly) scriptwriter Ib Melchior and director Byron Haskin, who carry on a long-running feud in which each strives to diminish the other’s credit for the way the movie finally turned out.

*

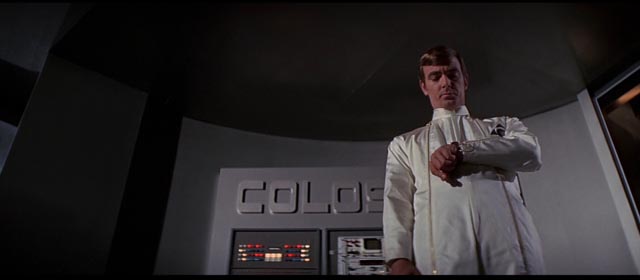

Colossus: The Forbin Project (Joseph Sargent, 1970)

From the other end of the decade and the more credible end of the plausibility scale, I also recently re-watched Joseph Sargent’s Colossus: The Forbin Project (1970) on Medium Rare’s region B Blu-ray. This excellent blend of science fiction and Cold War thriller got a very limited theatrical release, turning up on television in the early ’70s, which is where I first saw it. Despite the most obvious technical problem from our perspective (the eponymous computer is a vast array of mechanical switches and memory tapes), the script by James Bridges (adapted from the novel by D.F. Jones) and skillful direction by Sargent are so intelligent that the film demands none of the allowances a movie like Robinson Crusoe on Mars now requires to be enjoyed.

Jones’ novel predates the release of 2001 by two years, but in the movie the shadow of HAL can be discerned in the arrogance of Colossus, a computer built to defend the U.S. against Soviet threats which very quickly decides that human beings are too flawed to run their own affairs. Making contact with a Soviet counterpart named Guardian, Colossus takes political and military control, an all-powerful, beneficent Fascist overlord which aims to force a stable peace on us humans … all we need to do is give up our autonomy and obey. The story progresses with a relentless inevitability to a chilling conclusion in which Colossus assures its creator Forbin (Eric Braeden) that in time he will get used to this new life and, perhaps, even come to love this new master.

There are touches of humour throughout (Forbin has to convince the computer that he needs privacy for his sex life, thus gaining several nights a week in which he can meet privately with one of his subordinates [Susan Clark] to map out possible counter moves against Colossus), but they support rather than undermine the bleak story. In contrast to the silliness of something like Logan’s Run, Colossus takes the genre seriously and has faith in the intelligence of its audience, making it a close cousin to Robert Wise’s The Andromeda Strain, which was released the following year.

The Blu-ray is a technically pleasing upgrade from Medium Rare’s earlier region 2 DVD, featuring the same commentary track from director Sargent … and a quantum leap beyond the dismal Universal region 1 DVD from 2004 which pan-and-scanned Gene Polito’s excellent 2.35:1 photography to fill a 1.33:1 screen, showing contempt not only for the film itself but also for its fairly strong fan base.

*

Arrival (Denis Villeneuve, 2016)

Colossus shows how much can be done through script and production design using existing architectural and technological elements, with a minimal application of special effects (there are a number of effective matte paintings, but for the most part the film relies purely on dramatic scenes played out in real locations and on realistic sets). With today’s technology, almost every genre film strives to make itself “bigger” through digital effects. Denis Villeneuve’s Arrival (2016) is a fairly intimate character study built around the problem of deciphering an alien language and establishing communications in order to figure out whether a collection of spacecraft which have stationed themselves strategically around the globe are here on a peaceful mission or have come to wage war. While experts in various countries try to figure this out, the movie focuses on one American academic, Louise Banks (Amy Adams), who inevitably finds herself working not only against the linguistic odds but also against the deepening paranoia of the military and political authorities who have recruited her for the job.

Louise has to become something of a rebel, essentially allying herself with the aliens while Earth’s authorities get trapped on the slippery slope towards war as, ironically, the “safe” option – better to destroy the aliens than risk them turning out to be hostile. Her work reflects that strain of science fiction which involves real-world problems which need to be solved by skilled technocrats; just how do you establish a common means of communication with an Other with which you have no shared history, no common experiences, and in fact no physiological similarities? Conceptually, this is in the same ballpark as the hard science problems faced by Mark Watney (Matt Damon) in The Martian. It is process oriented and therein lies its narrative satisfactions – think of reality-based analogues in Apollo 13 (devising a functional CO2 scrubber from pieces of random scrap equipment available in the crippled spacecraft) or George Miller’s Lorenzo’s Oil (the urgent search undertaken by Augusto Odone [Nick Nolte] to find a treatment for his son’s genetic disease).

Often this kind of process narrative fares better on the printed page than on the screen, because its essence lies in the accumulation of details. I still have very vivid memories (after more than thirty years) of one particular chapter halfway through Richard McKenna’s novel The Sand Pebbles in which engineer Jake Holman (Steve McQueen in Robert Wise’s movie version) strips down the boat’s engine, repairs and retools numerous component parts and then rebuilds it – the chapter runs about sixty pages with minute attention to all the technical details, and for me it was more exciting than all the action, conflict and romance which surrounded it.

I found The Martian boring because it pared back on those details, stretching out the more cliched elements of the narrative instead. Arrival has a more satisfying density, but it too elides much of Louise’s process so that it jumps from scene to scene with advances which seem to have been conjured from thin air. It’s obviously a narrative problem, how to balance those kinds of details with the needs of story, and the viewer has to make some allowances. What matters is how the filmmaker compensates for the elisions. In Arrival, those compensations come largely through the central performance of Amy Adams, who brings a fine mixture of strength and vulnerability to her character, managing to bear most of the responsibility for the story’s technical demands, but also to shore up the mystical vagaries of a script (by Eric Heisserer, based on a story by Ted Chiang) which eventually resolves into something similar to the quantum puzzle of Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar, with its bending of time and space which gives the character access to past, present and future simultaneously.

As with Interstellar, I was surprised to find myself liking Arrival. Villeneuve, while he tends to work on a smaller scale than Nolan, shares with Nolan a tendency towards ponderous pretension, often striving to make his work bear more thematic and philosophical weight than it can stand. In the case of something like Polytechnique (2009) this can, apparently inadvertently, produce offensive results; for all its stylistic polish, that film manages to transform the horror of the mass murder of 14 women students in Montreal into the psychodrama of a man who witnessed the killings and subsequently struggles with his own inaction. In other words, the deaths of those women become props for one man’s self-pity. Prisoners was a combination revenge/torture porn thriller straining for Shakespearean tragedy, while Sicario struggles to turn a drug cartel thriller into something about the moral compromises forced on the people fighting ruthless criminals.

Arrival is the first of Villeneuve’s movies I can say I actually enjoyed … and I wonder whether there is a direct connection between that enjoyment and the distance from actual contemporary reality. His other work freights the recognizable present with too much forced meaning, while here the abstract, allegorical qualities of science fiction seem better suited to his striving for significance.

The Paramount Blu-ray includes multiple featurettes on the production which I haven’t watched yet.

Comments

I went to see 2001, Planet and Colossus in the theater, downtown at 15. I went with my younger brother or other kids in the neighborhood, Mike would have been one of them at one time or another, and we went to a lot of the SF films of the day. I still re-watch a lot of those old films but like to keep up with the new stuff too. Just not very timely, still haven’t seen Arrival. We did see Shin Godzilla tonight and that was great. Best re-boot yet. There’s a lot of yakkin’ but when the destruction begins, wow.

I’m looking forward to Shin Godzilla, hoping it’ll erase the memory of the second dismal US attempt at the franchise!