Summer viewing: short takes

Back in the late 1960s and early ’70s, I did most of my movie viewing on television. There were only two or three channels – no cable, just a broadcast signal pulled in with a rooftop antenna – but there were plenty of movies along with TV shows: regular Saturday evening movies, late shows, weekend matinees, even weekday afternoon shows which I’d catch when I got home from school. One of my most vivid memories, unbelievably, was my first viewing of Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom after school one afternoon, something which my 12-year-old self was totally unprepared for.

Then there were movies shown in the morning, before lunch, which I could watch when I stayed home sick. I can’t imagine who the intended audience was – stay-at-home Mums? kids like me? – but here again one of my clearest memories was of something totally inappropriate: I think it was a French film (dubbed, of course) set in a brothel. There were a lot of bare breasts and suggested sex. Not what you’d expect at 11:00AM on a weekday morning.

The biggest, most recent and mainstream movies, though, were generally reserved for Saturday night at 8:00 PM. It didn’t really matter what was showing; I’d watch anything. That was the slot in which I first saw Airport.

This all came back to me recently when I picked up a couple of discount Blu-rays which happened to be movies I had previously seen in that Saturday evening slot too many decades ago to contemplate comfortably. As it happens, they are also both John Wayne vehicles. And by an odd coincidence, both were written by western specialist Clair Huffaker, the majority of whose credits were in television.

*

John Wayne X 2

The War Wagon (1967) came along when the western was already a fading genre and its script (adapted from a novel called Badman by Huffaker) is built around the gimmick of the title – an armoured stagecoach with a rotating turret on the roof which houses a Gatling gun. This vehicle is used by unscrupulous businessman Pierce (Bruce Cabot), who years ago framed rancher Taw Jackson (Wayne) and got him sent to prison so Pierce could steal his land and exploit a rich vein of gold. Released from prison, Jackson returns to town to get revenge, specifically by raiding the armoured car when it’s carrying half-a-million in gold dust. In essence, The War Wagon is a heist movie, with Jackson putting together a team of misfits – gunslinger Lomax (Kirk Douglas), who once tried to kill him and has again been hired by Pierce to get Jackson out of the way; young explosives expert Billy Hyatt (Robert Walker Jr.), who happens to be an unreliable drunk; Levi Walking Bear (Howard Keel), an Indian who has turned his back on his people in order to fit into the white world which refuses to accept him; and Wes Fletcher (Keenan Wynn), one of Pierce’s employees who is aggressively paranoid about his much younger wife, to whom Billy is attracted. This gang devise an elaborate plan to overcome the wagon’s intimidating armaments and the twenty-odd riders who accompany it.

Director Burt Kennedy handles the material with a light touch, giving the movie something of a throwaway air, although there are passing references to the displacement of the native population, the hard lot of women in this violent “man’s world”, and the corruption of frontier society by the power of immoral rich men. Despite the star power in the cast and some nicely shot western landscapes (photographed by William H. Clothier, another western specialist and apparently a favourite of Wayne), The War Wagon feels like a small movie, lacking the grit and grandeur people like Leone and Peckinpah were injecting into the genre around the same time. And in the end the wagon itself never amounts to much, even though it seems poised to represent the awesome destructiveness of a fast-approaching future which will render an individual with a six-gun little more than a quaint anachronism.

Hellfighters (1968) recasts that lone hero as something more modern, part of a team using technology to combat the very dangers which that technology poses. Here Wayne plays Chance Buckman, a thinly-disguised version of Red Adair, a famous fighter of oil well fires. Chance runs a company out of Houston with a team of rugged guys – including old Wayne sidekicks Jay C. Flippen and, yet again, Bruce Cabot – who are ready to head anywhere in the world at a moment’s notice when an oil well blows.

In the stolid hands of director Andrew V. McLaglen, the movie bogs down in what amounts to a family soap opera (Chance’s fraught relationship with his estranged wife Madelyn [Vera Miles] and daughter Tish [Katherine Ross], the budding romance between Tish and Chance’s hot-headed employee Greg [Jim Hutton], plus various business stresses), which is interrupted at regular intervals by spectacularly staged sequences in which the crew use dangerous methods to douse those oil well fires. The technical details of the firefighting give the movie what value it has, stressing the hair-raising dangers the crew face as they work in close quarters with geysers of flaming oil and barrels of high explosives.

Wayne’s reactionary politics poke through in the final act with an oil field fire set off by Central American revolutionaries who lurk in the hills to take shots at the crew as they try to do their work; soon the country’s military, in concert with representatives of the U.S. State Department, show up to deal with the rebels and protect U.S. corporate interests.

Both films show Wayne relaxed comfortably into the star persona he had developed over decades as a rugged Hollywood leading man; but neither digs any deeper beneath that surface the way, say, Ford did in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) or Don Siegel did in The Shootist (1976).

Both Universal bare-bones disks have decent transfers.

*

Other recent viewing:

King Kong

(Merian C. Cooper & Ernest B. Schoedsack, 1933)

A much younger Bruce Cabot plays a key role as sailor John Driscoll in one of the greatest adventure movies ever made, the original King Kong (1933), which I just watched belatedly on the Blu-ray originally released in 2010. There are arguments for the film’s regressive attitudes towards “primitive” cultures and non-white peoples – arguments which have been made repeatedly over the years – and they are valid (the film carries its racial imperialism with unquestioning confidence), but it remains nonetheless one of the greatest works of cinematic imagination, a Beauty-and-the-Beast fairytale which juxtaposes an almost-realistic present – the Depression, with its crushing economic hardships – with a fantastic alternate world which exists outside of time, offering a thrilling antidote to the grinding concerns of its Depression-era audience.

The producer-director team of Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack brought to this fantasy a wealth of personal experience from their own past as explorer-filmmakers who had traveled to harsh and distant locations to bring back the epic narrative documentaries Grass (1925) and Chang (1927). They seemed to belong to an earlier age, that of the 19th Century explorers who returned with stories and artifacts from remote places which were invested by Europeans and Americans with a romance reflecting dissatisfaction with the constraints of “civilization”. Conceived as a character with a distinct personality, Kong is also a metaphor for all the “otherness” which colonialism and imperialists had exploited and destroyed in their greed to dominate and own all corners of the world. Given life and individuality by the script (Ruth Rose, James Creelman and Edgar Wallace) and the art of animator Willis O’Brien, the great ape is invested with most of the audience’s sympathy.

It’s been noted many times that the (usually) men who directed movies in Hollywood’s Golden Age (from the silents up through the ’50s) had come to the job with real life experience behind them, not least passage through the two World Wars, while from the ’60s on, more often than not, filmmakers’ experience was rooted in watching movies rather than living adventurous lives. Their life experience came through in the way these earlier filmmakers told stories and how they conceived of characters – in King Kong’s dynamic producer-adventurer Carl Denham (Robert Armstrong), Cooper and Schoedsack created a wry self-portrait – as well as in the texture and detail they added to those stories. Even something as fantastic as King Kong is rooted in a well-observed reality which bolsters the fantasy elements in a way generally missing from today’s CG-heavy blockbusters (including Peter Jackson’s awful, bloated remake).

Although to a CG-trained eye some of King Kong’s effects may look “crude” today, the film’s visual world is so dense and richly layered – those images of the island which combine miniatures, multiple planes of matte painting, live action and stop-motion creatures – that it has a sense of weight often lacking in CG environments no matter how detailed. But in addition to this, the imagery displays a beauty of design rooted in the inspiration the filmmakers drew from the etchings of Gustave Dore, resulting in a dreamlike fantasy given an air of material reality which the film retains despite all subsequent technical developments. The detail of those images is on spectacular display on the Blu-ray; the film looks better than it ever has before on home video.

The excellent presentation of the feature is supplemented with a huge amount of supporting material: a commentary track with Ray Harryhausen in conversation with Ken Ralston, and archival clips from Merian C. Cooper and Fay Wray; a one-hour documentary on the career of Cooper; seven featurettes about the production totaling almost three hours (rather too much of which is devoted to Peter Jackson and his then current remake); a reconstruction of the lost “spider pit” sequence; and some test footage from Willis O’Brien’s abortive Creation project.

*

The City of the Dead, aka Horror Hotel

(John Llewellyn Moxey, 1960)

Although conceived on a much smaller scale, more intimate than epic, John Llewellyn Moxey’s The City of the Dead (1960) has its own visual beauty, giving fantasy a tactile material quality. This very low budget horror film (essentially the first Amicus movie, produced by Max Rosenberg and Milton Subotsky) was made entirely on studio sets in England, though the story (written by George Baxt from an original treatment by Subotsky) takes place in New England, making it feel more authentically Lovecraftian than many adaptations of actual H.P. Lovecraft stories.

Like Mario Bava’s The Mask of Satan/Black Sunday, made the same year, and Roger Corman’s actual Lovecraft adaptation The Haunted Palace made three years later, The City of the Dead begins with a historical prologue in which villagers about to execute a witch (or warlock) are cursed by their victim along with their descendants. Then the bulk of the film takes place hundreds of years later as that curse is played out, in the case of Bava and Corman in the 19th Century, but here in the present.

What makes The City of the Dead doubly interesting is its structural similarities with another, far more famous and commercially successful movie which was made almost simultaneously: Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho. The character we presume to be the heroine, here Nan Barlow (Venetia Stevenson), travels off the beaten path and takes a room at a gloomy inn. A student of professor Alan Driscoll (Christopher Lee), she has come to do some research into the history of witchcraft in the village of Whitewood, rather than run away with her boss’ money, but surprisingly before the film is half over she falls prey to the hotel’s owner and her disappearance is investigated by her brother Richard (Dennis Lotis) and Patricia Russell (Betta St. John), a young local woman who had briefly befriended Nan; the pair eventually uncover a conspiracy of the witch cult which has lingered on in the village since Colonial times. Having discovered Nan’s fate and dispatched the witches who killed her, in the final shot Richard and Patricia discover the shriveled, burned body of the witch sitting in a chair in the shadowy hotel – just like Mrs. Bates.

Shot in atmospheric black-and-white by Desmond Dickinson, whose career spanned almost fifty years from the late ’20s to 1975, The City of the Dead has a striking visual quality which sets it apart from the more naturalistic British horror films of the period (like Horrors of the Black Museum, which Dickinson also shot just the previous year). The entire village of Whitewood was built inside a large soundstage and filled with an omnipresent swirling fog which makes it seem to be trapped in a permanent night, outside of time … an impression heightened by the fact that the silent inhabitants are the same people we see in the prologue, and by Moxey’s staging of moments with Nan which repeat almost exactly later in the film with Richard. The village is caught in a permanent, cyclical now which revolves around the rituals of the witch cult.

Although the “hero” Richard is pretty dull as a character, which is not helped by the tonally off performance of former singer Dennis Lotis, most of the cast is excellent, with Christopher Lee making an intense impression as an academic who seems to be a bit too invested in his gloomy subject. Venetia Stevenson’s Nan is a bit too naive, missing obvious clues to there being something definitely wrong in Whitewood, but Betta St. John is an appealing heroine, while the stand-outs are Patricia Jessel as the witch Elizabeth Selwyn and her present-day avatar Mrs. Newless and the imposing Valentine Dyall as her partner in the cult. Given the limited budget, the cast is quite sparse, but the members of the cult are a visually distinctive collection of faces which add to the film’s air of unease.

Arrow’s Blu-ray includes both the original English cut (The City of the Dead) and the slightly shorter U.S. version (Horror Hotel) – the biggest difference between the two is the excision of most of Elizabeth Selwyn’s curse in the prologue, an odd editorial choice given that it sets up everything which is to come. The extras have mostly been ported over from previous DVD editions – interviews with Moxey, Lee and Stevenson, commentaries by Moxey and Lee – supplemented with a brand new commentary from critic and author Jonathan Rigby which adds interesting details about the production and the initial unenthusiastic critical and box office response the movie received.

*

Blood (Andy Milligan, 1973)

Not surprisingly, Andy Milligan’s Blood (1973) lacks the elegance of Moxey’s film … it also lacks some of Milligan’s own usual perverse extremes. Made a few years after his productive sojourn in England, it takes standard Gothic elements and manages to derange them in interesting ways. Returning from the Continent after years away, Lawrence Orlovsky (Allan Berendt) rents a house (Andy’s own house on Staten Island) where he wants to work undisturbed on his quest for a cure for his own and his wife’s genetic afflictions. Lawrence is actually a descendant of Lawrence Talbot, the well-known werewolf, while his wife Regina (Hope Stansbury) was born into the Dracula line. But this is no story of tragic love – the couple, in typical Milligan fashion, are bitter and steeped in mutual animosity.

Orlovsky’s experiments involve the breeding of flesh-eating plants from which he extracts a serum which, at least temporarily, protects Regina from the awful effects of sunlight. This work with the plants unfortunately requires blood and meat from the household servants, who are gradually losing their limbs but for some reason remain loyal. Milligan’s script is packed with his usual acidic dialogue, the deformative make-up is amusingly crude, and the period costumes as inauthentic as the Staten Island house. Less extreme than his more famous movies, Blood nonetheless delivers what Milligan’s fans like in his films – a bitter cynicism about human behaviour and desire salted with dark humour.

As expected, the print used as a source for Code Red’s Blu-ray is ragged and faded, but all the damage seems appropriate, adding texture to Milligan’s view of life. (That said, it’s still a pity that no one is making any real effort to find and restore the best elements for his movies as the BFI did for their excellent double-feature Blu-ray of Nightbirds and The Body Beneath.)

If any evidence were needed that Andy Milligan was a genuine poverty row auteur, one need look no further than the accompanying feature on Code Red’s disk, Legacy of Satan (1974), the sole straight horror movie directed by Gerard Damiano, best known for Deep Throat (1972), The Devil in Miss Jones (1974) and numerous other porn titles. Although the technical quality is superior to Milligan’s film, this story of Satanists seducing a young woman into becoming their new priestess is dull and impersonal, obviously an attempt by Damiano to use the genre as a (temporary) way out of the porn ghetto. It lacks Milligan’s crazed energy and the nondescript cast provides none of the entertainment value of the overheated theatricality on display in Blood.

*

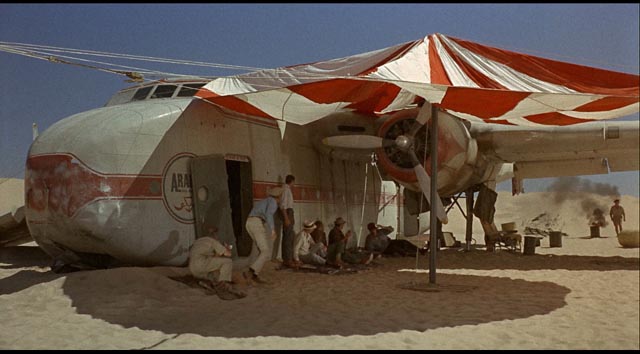

The Flight of the Phoenix (Robert Aldrich, 1965)

Made between the female-centric Southern Gothic Hush, Hush … Sweet Charlotte (1964) and the ultra-masculine action of The Dirty Dozen (1967), Robert Aldrich’s adaptation of Elleston Trevor’s novel The Flight of the Phoenix (scripted by frequent collaborator Lukas Heller) is inflected with the psychological darkness of the former while resisting the cartoonish heroism of the latter. This is an action/adventure story which refuses the easy satisfactions of the genre – which no doubt helped to make it a box office failure. That failure may go some way towards explaining Aldrich’s deliberate shift from a more personal perspective towards crass commercial calculation in The Dirty Dozen, which despite its box office success is possibly the most artless movie he ever made.

When a cargo plane carrying equipment and oilfield workers runs into a sandstorm over the Sahara and crash lands, pilot Frank Towns (James Stewart) is all-but crippled by feelings of guilt and inadequacy. His decisions had taken the plane off course and, with the radio not functioning, he knows that he has essentially doomed everyone to a lingering death. Despite being the captain, he doesn’t have the will to lead and the ragged group shoot off in all directions with poorly conceived plans, none of which are likely to save them. There’s a rigid military officer, Captain Harris (Peter Finch), who lords it over his reluctant sergeant, Watson (Ronald Fraser); Ernest Borgnine is Trucker Cobb, a worker who has had a psychological breakdown and is barely connected to reality; Richard Attenborough is co-pilot Lew Moran, who needs to defer to Towns’ authority even though he can see too clearly that the pilot isn’t capable of leading. But most importantly, there is a young German engineer, Heinrich Dorfmann (Hardy Kruger), who is blessed with a degree of self-assurance which immediately rubs Towns the wrong way when he asserts that it might be possible to construct a new, workable plane out of the damaged wreckage and fly them out.

Dorfmann gradually gains authority over the others and Towns is reluctantly dragged along as the group work around the clock to dismantle the plane and build the replacement before they run out of water. Towns feels vindicated in his disbelief in the plan when he learns that Dorfmann’s engineering experience is limited to designing radio-controlled model planes … but despite all the intra-group conflicts, the plan does finally pay off.

The film’s commercial failure may have had something to do with its refusal to subscribe to an inherently heroic view of human nature. These men don’t rise to the challenge of survival so much as fight against their own best interests every step of the way, and at the forefront is a decidedly unsympathetic performance from James Stewart, whose self-pity poses a dangerous risk to all of them. Survival ultimately rests on the absurd self-assurance of Dorfmann who, as the plan progresses, becomes more unpleasantly dictatorial – and yet is ultimately proved right.

The Flight of the Phoenix is not a feel-good adventure, but it is much more interesting and involving than the easy cliches of The Dirty Dozen. In fact at the level of craft, it’s one of Aldrich’s strongest films, with a fine attention to the details of the process these men are forced to engage in against their own conflicted natures.

The excellent hi-def transfer on Eureka’s Masters of Cinema Blu-ray is supplemented with the original trailer and a 25-minute interview with film historian Sheldon Hall (author of With Some Guts Behind It, a history of the production of Zulu) and a booklet containing an essay by Neil Sinyard.

Comments

One time, when we were watching Andy Milligan’s The Rats Are Coming, The Werewolves Are Here, people refunded my video rental money to turn the film off.

Ha ha ha! Philistines! But it’s true, I would only attempt to show one of Andy’s movies to a very select number of friends … though I guess that’s true of almost any movie; I tailor my suggestions to particular individuals because everyone has different tastes and standards.