Late summer viewing: more short takes

My late summer viewing has been pretty scattershot, a mix of old and recent movies, well-known and obscure (at least in my experience).

The Orchard End Murder (Christian Marnham, 1981)

I still order every release from the BFI’s Flipside series. Though they seem to come less and less frequently now, two more showed up this summer. I haven’t watched Maurice Hatton’s Long Shot yet, but I did watch Christian Marnham’s The Orchard End Murder. This short feature (it runs under an hour) was the first attempt at drama by someone who had made a number of short documentaries in the ’70s and it shows a filmmaker feeling his way through both narrative and tone. A young woman (Tracy Hyde), bored with her boyfriend’s country cricket match, wanders off through a picturesque village where she meets a pair of very eccentric men – the local station master and his big simple-minded companion. Invited in for tea, she comes to feel threatened and quickly leaves. In a nearby orchard, the hulking man (Clive Mantle) catches up with her and seems to want to apologize – he offers a basket of fresh apples – but then drags her off into a corner where he kills her while attempting rape. A police search eventually comes across the killer and his friend the station master (Bill Wallis) as they try to bury the body. As a narrative, the film peters out without much of a resolution, but its combination of quaintness and menace is quite unsettling, and Marnham gets some interestingly idiosyncratic performances from his cast. He also shows an impressive grasp of expressive camerawork, particularly in a stunning opening shot which uses a crane to observe the cricket game, then drift away over a lane to the nearby orchard where we gradually draw closer for a voyeuristic look at the woman and her boyfriend making love on a blanket while a half-glimpsed figure is seen spying on them from the nearby trees.

The dual-format edition includes some substantial interview featurettes with Marnham (38 minutes), Hyde (12 minutes), and David Wilkinson, who has a small part in the film and went on to become a prolific producer of documentaries and TV movies (13 minutes). Also included is one of Marnham’s documentary shorts, The Showman (1970, 25 minutes), about an Englishman with a carnival Wild West act, and a brief interview with Marnham about the doc (5 minutes).

*

Felicity (John D. Lamond, 1978)

John D. Lamond is a legendary Australian exploitation filmmaker (prominently featured in Mark Hartley’s documentary Not Quite Hollywood). Felicity was his first dramatic feature, a kind of junior Emmanuelle, in which a girl from a strict Catholic school goes on holiday to Hong Kong and learns about sex and love. As a softcore exploitation film, it’s perhaps most notable for sticking very closely to the girl’s point-of-view, seeing her experiences as a conscious exploration of her own erotic possibilities. While some of those experiences are less pleasant than others, she takes them all in stride on her way towards finding a balance between physical and emotional satisfaction. Much of the film plays like a travelogue, emphasizing the exoticism of Hong Kong. Truth is, as a movie it’s a bit dull and Lamond’s matter-of-fact approach deflates any potential erotic charge.

The Severin Blu-ray, however, is of real interest, because it also contains Lamond’s first two mondo films – The ABCs of Love and Sex (1978) and Australia After Dark (1975) – which like all mondo films combine sleazy exploitation elements with occasional documentary insights into then-current social attitudes. And once again, Lamond approached the material non-judgmentally, which gives his depiction of a mid-’70s gay wedding in Brisbane presided over by a local clergyman a surprising air of revelation given how long it took much of the developed world to catch up with this community.

To make the disk even more valuable as a record of a particular, somewhat disreputable backwater of Australian film history, each of the three features has a commentary with Lamond in conversation with Mark Hartley, plus some additional interviews culled from outtakes from Not Quite Hollywood – with Lamond, cinematographer Garry Wapshott, and Felicity star Glory Annen (who was born in Kenora, Ontario, and got the role only a year after taking up acting; her only previous substantial role was in Norman J. Warren’s British exploitation movie Prey [1977]).

*

Smokey and the Bandit (Hal Needham, 1977)

Burt Reynolds had been in the business for twenty years, gradually working his way up to stardom, when he finally hit it big with this redneck action comedy. It looked in a way as if he had been searching for the persona which would put him over the top after years of television appearances. He had followed Clint Eastwood to Italy to star in a spaghetti western for Sergio Corbucci (Navajo Joe, 1966); had tried his hand at adventure – in the Philippines for Impasse, Mexico for Shark (both 1969) and New Guinea for Skullduggery (1970); had tried his hand at cops and private detectives in Fuzz (1972), Shamus (1973) and Hustle (1975); but gradually homed in on a particular kind of Good Ol’ Boy Southerner which grew out of his Lewis in Deliverance (1972) and Paul Crewe in The Longest Yard (1974). This image was consolidated through White Lightning (1973), W.W. and the Dixie Dancekings (1975) and Gator (1976) before finally snapping into focus with Hal Needham’s Smokey and the Bandit (1977), a movie whose sole reason for existing was to display high speed car stunts through which Reynolds could crack wise and fall in love with Sally Fields’ runaway bride, and it was such a success that even Sam Peckinpah was tempted to cash in on what seemed to be a new genre with his epic disaster Convoy (1978).

Is Smokey and the Bandit actually a movie, or merely a calculated exercise in the manufacture of a product? There’s very little rationale for the film’s action – a wealthy promoter hires the Bandit to get a semi-load of beer from Texas to Georgia and along the way he picks up Carrie who has just ducked out of her wedding to the doofus son of blowhard sheriff Buford T. Justice (Jackie Gleason). It’s essentially an extended live-action version of a Roadrunner cartoon with appropriately cartoonish characters who need to do nothing more than provide a pretext for those car stunts. Yes, it’s mildly amusing, but it’s also kind of repetitive and pointless. And yet this was the movie that made Reynolds a big box office star, eventually leading to retreads with Smokey and the Bandit 2 (1980) and The Cannonball Run (1981). But having found this persona, the actor immediately tried to use his stardom to branch out, with Michael Ritchie’s interesting but uneven Semi-Tough (1977), the Reynolds-directed black comedy about suicide The End (1978), and Alan J. Pakula’s romantic comedy Starting Over (1979). Perhaps his career was all over the place – comedies, crime movies, even a musical and a remake of a Truffaut film – because he was always more of a character actor than a star. As he got older, he certainly seemed to settle comfortably into distinctive supporting roles, getting an Oscar nomination and Golden Globe win for his turn as a porn director in Boogie Nights (1997).

The 40th anniversary dual-format edition of Smokey and the Bandit includes a couple of featurettes on the making of the movie plus a feature-length documentary on Reynolds’ personal and professional relationship with Hal Needham.

*

The Missouri Breaks (Arthur Penn, 1976)

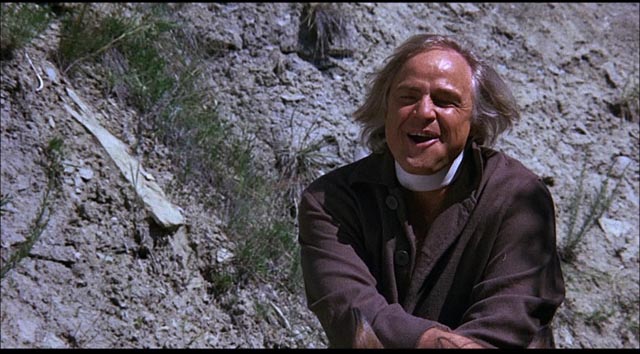

The third of three westerns directed by Arthur Penn, The Missouri Breaks (1976) was a flop when first released. In production, it had been much anticipated because it co-starred Marlon Brando and Jack Nicholson, two of Hollywood’s biggest and most distinctive stars. The script was an original by the idiosyncratic novelist Thomas McGuane, while Penn himself, despite an uneven record both critically and commercially, was a respected, award-winning filmmaker. But whatever people were expecting, The Missouri Breaks wasn’t it. Its tone defied mainstream standards, even that late in the evolution of the western. Elegiac, lyrical, absurdly comic, with bursts of horrific violence, it was unsettling and many critics laid the blame on Brando because here was one of his most outrageous performances as the sadistic enforcer Lee Clayton hired by rancher Braxton (John McLiam) to get rid of a band of rustlers lead by Tom Logan (Nicholson).

Although the film covers some of the same ground as Peckinpah’s westerns – particularly The Ballad of Cable Hogue and Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid – it’s not quite so easily grasped. McGuane’s vision of the West is of the inextricable intertwining of self-righteousness, greed and violence which props up and ultimately defines the American dream of individualism and capitalist success. Braxton owns vast stretches of land and lords it over everyone within reach; Logan dreams of something smaller but nonetheless similar, a ranch of his own, a piece of land to support him. The major difference between the two men is one of scale – Braxton uses violence to maintain his property, but that property just happens to have been stolen a while ago from its previous owners. His rights lie in that history of theft, yet he is legally justified in hiring a vicious killer to rid him of someone who wants only to take in turn a small part of what he owns.

McGuane’s script is full of wit and personality, the scenes among Logan’s gang striking what seems to be an authentic tone as they plot their petty crimes and tell stories to one another. This group is more egalitarian than Braxton’s patriarchy and their very looseness makes them vulnerable to the single-minded predation of Clayton, who amuses himself in finding humiliating ways to destroy his targets. Peckinpah lamented the disappearance of the mythic West; Penn and McGuane suggest that the myth was never rooted in reality, that America was built on violence which justified itself with self-aggrandizing stories. The Missouri Breaks is a rich and nuanced black comedy which punches holes in a long-cherished self-image, and although its reputation has improved in the intervening decades it remains contentious – look at the diametrically opposed views of Brando’s performance held by Glenn Erickson and Mike Sutton. Personally, I think it represents Penn, Nicholson and Brando at their best, with the added benefit of a superb supporting cast (Randy Quaid, Frederic Forrest, Harry Dean Stanton among others in Logan’s gang), with Kathleen Lloyd a stand-out as Braxton’s daughter Jane, who becomes attracted to Logan.

The Kino Lorber Blu-ray is unfortunately devoid of extras. The image is slightly soft and a bit murky, reflecting the original photographic style (it was shot by Michael C. Butler, who coincidentally went on to shoot both Smokey and the Bandit 2 and The Cannonball Run).

*

The Hateful Eight (Quentin Tarantino, 2015)

Given my dislike of much of Quentin Tarantino’s work, I was surprised to find that I almost liked the first half or so of The Hateful Eight. I hadn’t bothered to see it in a theatre because I despised Django Unchained so much and nothing I’d read about it suggested I should take a look. But then I heard Jennifer Jason Leigh’s conversation with Marc Maron on his WTF podcast and her enthusiasm for the movie prompted me to give it a try.

Although the gimmick of shooting on film in Ultra Panavision 70 in itself is of only passing interest, using that format with its 2.76:1 aspect ratio on a film which is written like a play, taking place almost entirely on one interior set, does have a kind of perverse appeal. But before we get to that set, there’s a long, languorous introduction in a snowy mountain landscape where Tarantino takes his time to introduce most of his characters. This is the kind of thing he does best, letting conversations play with odd asides and non-sequiturs, giving the characters a quirky theatrical life. The old dictum that “action is character” is upended by Tarantino; in his movies, for all the action that eventually unfolds, conversation is character. By the time these particular characters gather at the snowed-in waystation, various connections and conflicts have been clearly established and the movie’s business is to see where those connections and conflicts lead.

Inside the waystation, it becomes clear that Tarantino wants to use this location and its inhabitants as the basis for a kind of Agatha Christie countryhouse mystery. People die, secrets are revealed .. and then about two-thirds of the way through the narrative line is ruptured and the story returns to its beginning, now seen from a different point of view which explains what’s been happening … but in its repetition of the plot all tension is deflated and Tarantino is merely telling us the story rather than dramatizing it. It’s as if the final scene in which Poirot gathers the countryhouse inhabitants together to reveal the identity of the murderer was being inflated to fill a third of the running time.

At this point, with the movie having lost audience engagement – well, my engagement, anyway – the viewer has time to contemplate what isn’t working. I had a couple of problems with it. First, there’s that queasy glee Tarantino always shows towards sadistic violence, in this case mostly directed towards the physical abuse Leigh’s character is subjected to. She’s repeatedly punched in the face, beaten and clubbed, becoming a bloody, bruised mess … which, as is so often the case with Tarantino, we are supposed to find funny.

On a broader level, despite the colourful cast – Kurt Russell, Samuel L. Jackson, Bruce Dern, Tim Roth, Michael Madsen, Demián Bichir, Walton Goggins, Channing Tatum and Leigh – these characters are never convincing as figures either from the actual West or from the fantasy West of Hollywood movies. The whole elaborate edifice is like a simulacrum of a western which never connects with the real thing; Tarantino’s sensibilities as a writer and director are too modern, too urban to find the right tone for this story. In the end, it’s all play acting which never connects with what it’s trying to refer to.[1]

The Blu-ray contains the shorter theatrical release (168 minutes), not the longer roadshow version (187 minutes), but I can’t imagine what those missing twenty minutes might contain. There are only a couple of brief disposable featurettes to supplement the movie.

*

Jackie Brown (Quentin Tarantino, 1997)

Irritated by The Hateful Eight, I decided to go back and re-watch the twenty-year-old Jackie Brown to see how it holds up. When I first saw Tarantino’s Elmore Leonard adaptation on its original theatrical release, I found it a bit dull, but on several subsequent viewings I came to see it as his best film – less audaciously flashy than Pulp Fiction (which I also just re-watched; it wears its cleverness on its sleeve, amusing but not engaging on a deeper dramatic level), but more firmly rooted in sympathetic characters. Commercially, it was less successful than its predecessor and that may be at least in part due to the fact that it’s a story about weary middle-aged characters. The heart of the movie is the tentative relationship between Jackie (Pam Grier) – a down-on-her-luck flight attendant working for a crap minor airline who supplements her income by providing courier services to a criminal named Ordell Robbie (Samuel L. Jackson) – and Max Cherry (Robert Forster), a bail bondsman who meets her when Ordell arranges bail for her after she’s busted by the feds.

The plot is convoluted, with the feds putting pressure on Jackie to trap Ordell, while she and Max devise a scheme to trick everyone else so that she can end up with all the money herself. Jackson plays one of Tarantino’s patented motor-mouth black guys, and there are moments of abrupt violence, but what keeps the movie together are the strong characterizations – from Grier, Forster and particularly Robert De Niro as Ordell’s slow-witted protege and Bridget Fonda as Ordell’s kind-of girlfriend. Here Tarantino’s loose, drawn out scenes – which are more about the characters engaging with each other than moving the plot along – have a natural rhythm not always apparent in The Hateful Eight, seeming to confirm that he’s more comfortable with a contemporary urban milieu than the remote Old West.

*

Out of Sight (Steven Soderbergh, 1998)

And speaking of Elmore Leonard, by a strange coincidence one of his novels also provided the basis for my favourite Steven Soderbergh movie, which was made the following year. I just re-watched Out of Sight and it too holds up really well. Like Jackie Brown, this centres on a tentative love story involving a character who’s essentially a failure. Jack Foley (George Clooney), an unsuccessful bank robber, has been in and out of prison most of his life. While inside, he gets close to rich businessman Ripley (Albert Brooks), whom he protects from predatory con Maurice (Don Cheadle), and when he gets out he expects the businessman to return the favour … only to find himself humiliated. Meanwhile, Maurice is planning to break into the businessman’s house and steal a fortune reputed to be stashed away inside.

While Foley is unwillingly caught up in the plan, he also gets involved with U.S. Marshal Karen Sisco (Jennifer Lopez). Like Jackie Brown, Out of Sight has a complicated plot with multiple characters intersecting at cross-purposes, further complicated by the use of multiple timelines. Soderbergh, working from a tight, witty script by Scott Frank, weaves these together without overt signals, trusting the audience to construct a coherent narrative from the various parts while concentrating on the characters and their relationships. Everyone – Foley, Sisco, Ripley and Maurice as well as Foley’s buddy Buddy Bragg (Ving Rhames), Karen’s dad (Dennis Farina) and gang members Glenn (Steve Zahn) and Chino (Luis Guzman) – is given depth and the cast works beautifully together as an ensemble.

Soderbergh too often seems facile (the shallow and smug Oceans movies), but here makes great entertainment look effortless.

_______________________________________________________________

(1.) Antoine Fuqua’s remake of The Magnificent Seven (2016) suffers from the same problem; despite the landscapes and a western town built to resemble old familiar backlot sets, nothing feels authentic, including the complete absence of any reference to the fact that the hero is Black and we first meet him shooting a bunch of white men in a saloon. The villagers here are not penniless peasants being preyed on by a vicious gang of armed opportunists, but rather middle class settlers being abused and exploited by a vicious capitalist who wants them off their land so he can mine all the gold beneath the ground. While there may be a suggestion that the underpinnings of Manifest Destiny were morally bankrupt, the true victims of that westward imperative are essentially erased (merely hinted at by a token Native American among the Seven), while the idea of class amongst the whites, good and bad, is also elided. The last-minute insertion of a racially loaded backstory at the climax carries no weight because it comes out of nowhere. For all the slick photography, the high-power cast, and the large-scale action sequences, the script by Richard Wenk and Nic Pizzolatto fails completely on the most basic dramatic level and Fuqua never finds a period-appropriate visual style. (return)

Comments