Miscellaneous notes: Severin Films

Jack the Ripper (Robert S. Baker & Monty Berman, 1959)

Considering the amount of effort Severin put into their special edition Blu-ray of Robert S. Baker and Monty Berman’s Jack the Ripper (1959), it probably seems churlish to say that I was disappointed. The two-disk set contains three different versions of the movie – the original British release, the U.S. release (slightly altered by distributor Joseph E. Levine), and the “continental” version (on DVD) with several scenes displaying some nudity. Extras include a commentary on the British version with Baker, screenwriter Jimmy Sangster and assistant director Peter Manley, moderated by Marcus Hearn. The Blu-ray also includes the alternate continental scenes, an interview with Denis Meikle about film versions of the Ripper story, a U.S. theatrical trailer and a stills and poster gallery. The DVD includes an interview with the French re-issue distributor Alain Petit. Although each version is preceded by a brief text about the transfer, the information provided leaves a lot of questions.

First of all, there are apparently no original elements available for any version. The British version, we’re told, was mastered from an HD transfer made around 2005, which was inexplicably pan-and-scanned. Who made the transfer and why, at that late date, they would have cropped the image is a mystery. The U.S. version, a new HD transfer from a 1960 release print, is at least in what appears to be the correct aspect ratio – but the print itself shows a lot of damage, with numerous missing frames creating jumps in many scenes and pronounced scratches throughout. The continental version is more puzzling still. The text note states that it was created by inserting scenes from a French DVD into the British transfer; which means it also is pan-and-scanned. Yet in his interview, Petit mentions that his team had located a pristine internegative of the French-language version, which suggests that it would have been in the wider aspect ratio. If this was the case, then Severin must have cropped the new scenes themselves to conform with the British transfer. And if this was the case, and since this version is presented by Severin on DVD anyway, why didn’t they simply port over the complete French DVD? There are no answers provided here. (A search of Amazon France turns up a DVD with a claimed aspect ratio of 1.33: 1, but it’s not clear whether this is pan-and-scanned or transferred open-matte.)

As for the film itself, it marks that period when, in the wake of Hammer’s early successes, British horror was pushing against the limits imposed by the BBFC censors. Although Baker and Berman made their first forays into horror with more obvious Hammer imitations – Blood of the Vampire (1958, directed by Henry Cass) and the Quatermass-influenced The Trollenberg Terror (aka The Crawling Eye, also 1958, directed by Quentin Lawrence) – and were ultimately best-known for the many television series they produced in the 1960s and ’70s (The Saint, The Baron, The Champions, Department S and so on), their most significant film work was a brief series of features which combined history and horror, beginning with Jack the Ripper in 1959, quickly followed by The Flesh and the Fiends (written and directed by John Gilling) and The Siege of Sidney Street (directed by Baker and Berman), both released in 1960. These films all displayed an atmospheric attention to period detail and in the case of the latter two a somewhat faithful attention to the actual history (the case of resurrectionists Burke and Hare in 1820s Edinburgh in the former, and in the latter the notorious battle between police and anarchists in London in 1911).

Jack the Ripper, however, apart from using the name and the East End location, bears little resemblance to the actual crimes. As in many fictional treatments of the case, Sangster’s script proposes a motive rooted in personal vengeance – specifically (as in John Brahm’s The Lodger [1944]) revenge against prostitutes for the death of a loved one who was “contaminated” by one particular woman’s touch. Sangster packs his narrative with so many red herrings that when the Ripper’s identity is finally revealed there’s not much sense of surprise. The film’s main strength is its atmospheric evocation of the dank streets and alleys of Whitechapel (shot by Baker and Berman themselves). There’s a romance (between one of the investigators and the ward of a surgeon at the local charity hospital, who himself may or may not be the killer) and brief hints of conflict between the policeman in charge of the case and anxious politicians and bureaucrats who want things wrapped up quickly, whether or not the man who’s arrested is the actual killer.

Weaknesses include a cliched mute hunchback, who works at the hospital and is targeted by increasingly angry locals who begin to take vigilante action, and the staging of the murders themselves. Despite being informed several times that the killer does his work with surgical precision, what we see (obscured by shadows and oblique camera angles to avoid the censor’s probable interference) is a figure quickly stabbing each victim a few times with a large knife. The psychopathology suggested by the actual murders is passed over in favour of something more routine, and the climactic moments belong more to a cheap penny dreadful than history or plausible drama.

*

By coincidence, the day after this disk arrived in the mail, I found a remaindered copy of a massive book about the Ripper case in a local bookstore. I picked up They All Love Jack: Busting the Ripper (Harper: 2015) not simply because the case was currently in mind, but rather because it was written by none other than Bruce Robinson, writer-director of one of my favourite films: Withnail and I. Despite its daunting size (800+ pages), I’ll tackle it as soon as I’ve finished reading Steve Ryfle and Ed Godziszewski’s biography of Ishiro Honda.

*

The Otherworld (Richard Stanley, 2013)

In the same package as Jack the Ripper, I also received Severin’s Blu-ray of Richard Stanley’s The Otherworld (2013). Stanley remains best-known for the debacle of The Island of Doctor Moreau, but apart from that fiasco, and his two early features – Hardware (1990) and Dust Devil (1992), both made in his mid-20s – his most interesting work is a handful of documentaries, beginning with Voice of the Moon (1990), an impressionistic portrait of the Afghani Mujahideen fighting against the Russian occupation, which Stanley made under arduous conditions when he was just twenty-four. With time out for Doctor Moreau, there was a seven year gap between the concept music video Brave (1994), a collaboration with the “neo-progressive” band Marillion, and Stanley’s next (and best) film, The Secret Glory (2001), a documentary about Nazi occultist Otto Hahn’s search for the Holy Grail, which was followed the next year by The White Darkness, another impressionistic documentary, this time dealing with contemporary voodoo practices in Haiti.

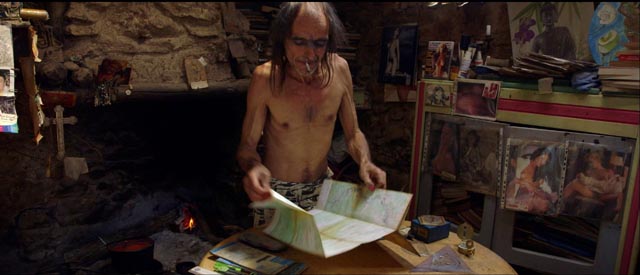

It’s clear from the documentaries (and Dust Devil) that Stanley is drawn to mysticism, and his latest work, an offshoot of The Secret Glory, finally places the director centre stage as he recounts his own seemingly supernatural experience. The setting is Montségur, an area of France with a long occult tradition. This was the stronghold of the Cathars, a sect deemed heretic by the Medieval Church against which the Pope ordered a crusade; after a lengthy siege, the Cathars surrendered to an army of 10,000 and 244 members of the sect were burned to death for refusing to renounce their beliefs.

Considered a site where the boundaries between this world and the next are permeable, Montségur receives many visitors every year seeking some form of enlightenment, while many of those who live nearby believe in the power of the place. After filming in the locale for The Secret Glory, Stanley found himself returning repeatedly until on one particular occasion, in the company of his friend Scarlett Amaris, the boundaries seemed to disappear and they had a vision of a powerful female figure who evoked an overwhelming emotional response. The desire to repeat the experience brought the pair back again on other occasions … but when they finally did have a second experience, it turned out to be more terrifying than enlightening, a sense of themselves being almost obliterated by these powerful occult forces and barely making it back to this world.

The Otherworld is Stanley’s attempt to come to grips with an experience he doesn’t understand, and as he circles around those two encounters he explores the region surrounding Montségur and speaks with other people who have been drawn to live there. While some seem quite eccentric, others talk calmly and reasonably about what they feel to be the transformative atmosphere of the site. While it might be easy to dismiss all this as New Age delusions, Stanley manages to evoke a powerful sense of mystery around the location, beautifully shot by cinematographer Karim Hussain and enhanced by an atmospheric score by Simon Boswell (who has scored all of Stanley’s films). If nothing else, the film makes you want to visit Montségur yourself – the landscape and the ruins dominating it are spectacular.

Richard Stanley himself is a genuine eccentric whose personality permeates his unconventional films and whether or not the experience at the centre of The Otherworld is “real” or a subjective illusion, the film is engaging and thought-provoking.

Severin’s Blu-ray renders the original digital photography with luminous clarity. The feature is accompanied by several deleted scenes and a half-hour featurette which isn’t quite a making-of, but rather an impressionistic companion piece, observing the film from one step further back. The only fault (if I can call it that) is the absence of a commentary track … all the more noticeable since Severin’s limited edition also includes a DVD of the three earlier documentaries which do feature commentaries. (I haven’t checked these out yet, but Mondo Digital reports that they’re new, not ported over from Subversive Cinema’s 2006 five-disk DVD edition of Dust Devil.)

*

Lucio Fulci

In yet one more odd coincidence, Uranie, one of the oddest characters in The Otherworld, cites the films of Lucio Fulci as his own gateway into the mysteries of Montségur. It happens that Fulci has been on my mind lately, partly because just before Christmas I received my copy of FAB Press’ revised and updated edition of Stephen Thrower’s book about Fulci, Beyond Terror, and partly because I’ve been introducing a co-worker to the pleasures of Italian horror and the giallo, including the films of Fulci along with Argento, Bava and Luciano Ercoli. This co-worker lent me his copy of the Zombie 3 DVD, which I hadn’t seen – largely because of its poor reputation; Fulci essentially abandoned it and it was completed by uber-hack Bruno Mattei; its reputation was borne out, from a half-assed script which draws more from George Romero’s The Crazies than the original Living Dead trilogy to poorly staged action scenes and completely disposable characters (pretty much all of whom are indeed disposed of as the movie unwinds). There seems to be little of Fulci here as it comes closer to Mattei’s own Hell of the Living Dead than to Zombie or City of the Living Dead.

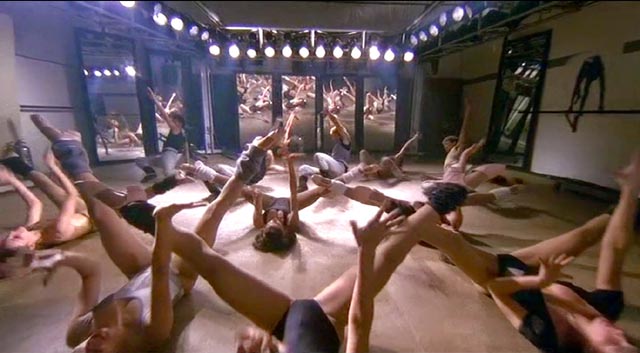

Because of this exchange, I dug out copies of some of Fulci’s later movies – the ones with increasingly low reputations, which I’d never gotten around to watching – beginning with Murder Rock (or as it says on-screen, Murder Rock Dancing Death). Although this starts out in a bizarrely promising way with an extremely extended energetic (and sweaty) dance sequence in some kind of performing arts academy in New York – slipping quickly into a seemingly self-aware parody of the Flashdance aesthetic – it soon descends into lazy giallo territory, with someone knocking off the students one-by-one.

Setting aside The Door Into Silence, The House of Clocks, The Sweet House of Horrors and The New Gladiators, I raised my sights and finally watched Beatrice Cenci (under the unappealing title Conspiracy of Torture), a disk I’ve had for years but somehow never got around to before. Released in 1969, it predates Fulci’s horrors and gialli, and has a reputation for being among his best. Based on actual events in the 16th Century, it tells the story of the daughter of a nobleman who, having been raped by her father, plots with her mother and lover to kill the man. Although they try to make it appear he died in a drunken accident, all three are tried, condemned and executed. Fulci recounts the story in a series of nested flashbacks which reveal the true motivation (the rape) quite late in the film.

One of Fulci’s own favourites among his movies, it deals with the brutal story without indulging in the kind of excesses he would soon become famous for, which in retrospect makes it surprisingly restrained in comparison with the gialli and horrors to come in the following two decades.

Comments