John Murray Anderson’s King of Jazz (1930): Criterion Blu-ray review

I should confess up front that my knowledge of jazz is woefully lacking. Perhaps somewhat perversely, my interest in Criterion’s release of John Murray Anderson’s King of Jazz (1930) rested largely on the fact that it was shot using the two-strip Technicolor process, a technology which produced an image with often striking visual qualities. Using only two primary colours (red and green), it could result in vivid yet not-quite-natural hues and I find the artificiality aesthetically pleasing. On this point, King of Jazz turns out to be a visual feast of eye-popping inventiveness which pushed the possibilities far beyond the limitations so often imposed by the Technicolor corporation.

As a proprietary technology, Technicolor was controlled by the corporation to a dictatorial degree. Any production making use of it was assigned an advisor who was there to make sure the company’s reputation wasn’t damaged by filmmakers who might want to experiment with colour rather than simply strive to achieve what the company considered “natural”. Technicolor’s management wasn’t interested in exploring visual artistry, so there was almost always some tension between their advisors and cinematographers … which is why it’s always a pleasure to discover a film which breaks free of those constrictions, as King of Jazz does under the guidance of director Anderson and cameraman Hal Mohr.

King of Jazz was conceived as a prestige project for Universal by Carl Laemmle Jr. (still only 22 years old, although he’d already been head of production for two years, having been handed the studio by his father on his 21st birthday). The arrival of sound had already created a taste for musicals – or at least musical numbers. The “first talkie” was, of course, The Jazz Singer (1927), also shot by Mohr; showcasing popular music stars like Al Jolson seemed a no-brainer. And (unknown to me until this release) there was no bigger recording and radio star in the ’20s than band-leader Paul Whiteman, who somewhat to his own discomfort had been dubbed “the King of Jazz”. Apparently, he was a friend of many major Black artists at the time and drew on their work, but the culture barred his use of Black musicians … the relationship between popular music and Black culture is one uneasy subtext of the film, although the copious supplements on Criterion’s disk indicate that this was not simply a case of a white man (the irony of his name notwithstanding!) appropriating the substance of a suppressed subculture. Whiteman used Black musicians to orchestrate numbers for his band.

Paul Whiteman seems an unlikely star for the movies – a large, doughy figure with a thin moustache and an impish expression – yet the original idea was to write a dramatic narrative around him, in fact to make him the centre of a fictionalized romantic story. He had no interest in being an actor and, given his position, was able to reject each script as it was written. But even without a ready script, Laemmle began to spend money. With Paul Fejos tagged to direct, vast sets were constructed along the lines of those used for the director’s 1929 feature Broadway (a large-scale miniature of Times Square built for that film turns up during one number in King of Jazz). But as things dragged on, and script after script was ditched, Fejos departed and in one of those instances where the obvious remains too long hidden, it was finally realized that the best use of Whiteman’s talents would be as ringmaster of an elaborate revue – a collage of musical numbers and comedy skits reminiscent of Broadway shows and vaudeville.

Unfortunately for Laemmle, Universal and everyone else involved, many others had already had this idea and the late ’20s saw a glut of revues on the market, most shot with little imagination – often a camera would simply be locked down in front of a stage while the acts came and went. Laemmle’s ambitions for a quality product meant that, after a belated start, production proceeded slowly and very expensively, with the film being completed and released after audiences had lost interest in what was too often a tedious and impoverished genre. It didn’t matter that King of Jazz was genuinely spectacular and innovative; the audience was simply no longer there and it flopped with no possibility of recouping its $1.5-2 million budget.

By the time it was re-edited and re-released in 1933, its format seemed even more outdated as the popular musicals of the Depression were now built around stories and characters, rather than simply isolated acts. And yet, the film’s considerable influence can be seen in retrospect.

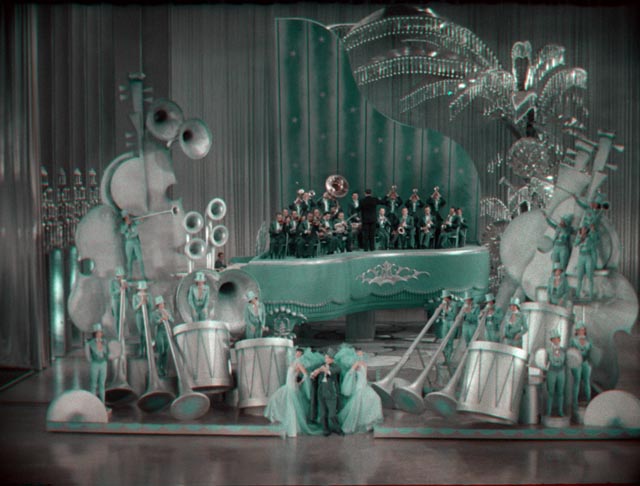

Once the revue idea took hold, Universal hired one of the most successful purveyors of the form on Broadway to direct. John Murray Anderson brought with him to this, his only movie, his vision of elaborate production numbers; but more importantly, along with Mohr, he strove to find ways not simply to record those numbers on film, but rather to create them as specifically cinematic events. Using the giant sets and the custom-built crane which Fejos and Mohr had designed for their film Broadway, Anderson is constantly searching for ways to view the performances which would otherwise be impossible. Here we see the prototypes for Busby Berkeley’s geometric compositions of synchronized dancers … but without a unifying narrative, each number stands alone and King of Jazz lives or dies on the individual strengths of those numbers.

As with any revue (or television variety show), there’s pretty much something here for everyone, but not everything will appeal to all viewers. However, as the saying goes, if you don’t like something, just stick around for the next performance. And there’s certainly enough variety and invention in the film to sustain interest through its 100 minutes.

What form the film has is provided by the idea that this is Paul Whiteman’s scrapbook, an eclectic collection of styles which display the range of his band and the personal appeal of multiple different performers. As for “jazz”, it soon becomes apparent that what we are getting here is rather a survey of various pop styles, which may or may not draw on jazz. There are ballads, waltzes, specialty numbers, most given a big melodic sound. In short, the film is a time capsule of popular taste at the end of the ’20s.

But before we get to this, we are offered an animated prologue which, according to master of ceremonies Charles Irwin, explains how Paul Whiteman was crowned “the King of Jazz”. Directed by Walter Lantz (who later gave us Woody the Woodpecker), this is in that early style of rubbery animation, with animate and inanimate objects alike bending, stretching and flowing without regard to the laws of physics or anatomy. What is most significant is that this short was the first colour cartoon. It begins with Whiteman hunting in “Africa”, being pursued by a lion, which he tames with music … and then throws in various other elements, including a monkey, an elephant and a chorus line of caricatured Africans, the first of very few references to any Black influence on the music.

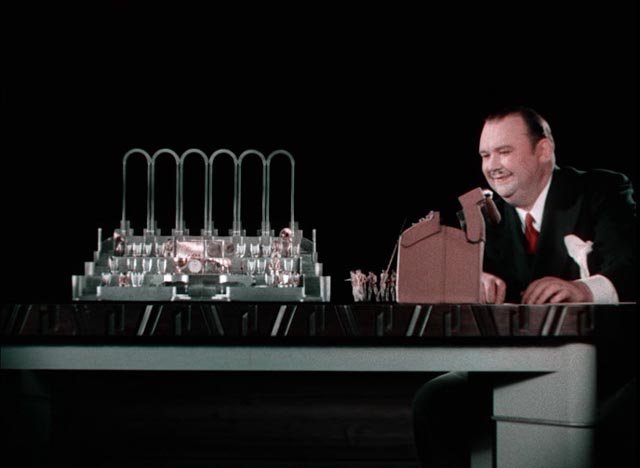

Following the cartoon, Anderson creates the first of the film’s many visually striking images as Whiteman begins to introduce his band by opening a small bag out of which the musicians climb onto a tabletop and make their way to the elaborate bandstand. The effect is flawless … and a precursor to similar tricks in James Whale’s Bride of Frankenstein (1935), Tod Browning’s The Devil-Doll (1936) and Ernest B. Schoedsack’s Dr. Cyclops (1940), not to mention countless ’50s B-movies and ’60s TV shows, none of which did it better than here.

During the band’s introduction, in which various musicians get brief solos, the film declares its visual ambitions with a striking use of colour which pushes the two-strip technology well past Technicolor-imposed limits. There is no interest here in using colour naturalistically; rather Anderson and Mohr intend to explore the expressive possibilities. One of the things they do here and in later sequences is to exploit the duality of the red-green separation of colours. They divide the image into quarters – left and right foreground, left and right background – with each quarter dominated by a particular hue, but alternating between background and foreground. Using colour design and filtered lights gives many images an almost three-dimensional quality.

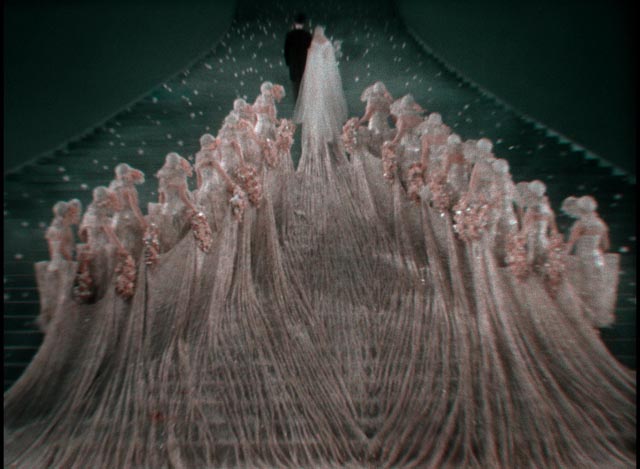

This brief introduction is followed immediately by what turns out to be the most plodding number in the film, a recreation of something Anderson had previously directed on stage. “My Bridal Veil” is a somewhat mawkish paean to a woman’s romantic submission to her man, with singer Jeanette Loff witnessing a parade of elaborately costumed women who descend a large staircase to establish her as the latest in a long historical line of brides. Herman Rosse’s set and costume designs are impressive and the song culminates in Loff’s ascent up an even bigger staircase with her groom, trailed by a vast (and very expensive) lacy train held by a company of bridesmaids. While visually impressive, with a skilled use of double exposure, the number bogs the film down before it’s achieved any momentum.

Up next is “I’d Like to Do Things For You”, in which one of the period’s oddest affectations is foregrounded – adults singing in tiny childish voices (immortalized by Betty Boop, who first appeared on screen the same year). It’s difficult now to comprehend the appeal. But apart from the irritant of Jeanie Lang’s squeaking out her cutesy vocals to Whiteman, the number gets interesting in its second part, with a duet between William Kent and Grace Hayes which turns the sentiments of the lyrics on their head; as Hayes sings of her desire to “do things for” Kent, she essentially beats him up and rips his clothes off, while he uses a thin, childish voice to placate her – the subtext of this romantic little ditty becomes an inversion of spousal abuse for “comic” effect.

The next sequence introduces The Rhythm Boys discussing their musical direction on a stylized penthouse set. Featuring Harry Barris, Al Rinker and a pre-stardom Bing Crosby, dressed in tuxedos, they perform harmonies in an engagingly relaxed way. Crosby was originally intended to have a more prominent role in the production, but soon after shooting began, he was arrested for drunk driving and, having mouthed off to the judge, was sentenced to two months in jail. Although he was let out during days in order to shoot, Anderson was annoyed and took away his big number – “Song of the Dawn” – and he appears only intermittently in ensemble numbers.

That song was reassigned to John Boles, an actor with a rather wooden presence. But before he got to Bing’s big number, he sings “Monterey” as a man reminiscing about a past romance. As he sings, a large portrait on the wall behind him comes to life and we’re transported to a Latin-flavoured set where an elaborately costumed woman (Jeanette Loff again) sits atop a wall, while Spanish dancers swirl below. Here, Anderson evokes a bit of Méliès’ magic to animate the painting.

After a comic number by Jack White – about wanting to open a fish store, and strangely getting machine-gunned during the war — “On a Bench in the Park” is an ensemble number which starts with couples wooing, then larger groups, and finally a crowd on an elaborate set which rotates into view covered with dancers, and then musicians. This climaxes in an odd moment, as Whiteman finally turns towards the camera and reveals a smiling little Black girl on his lap. The absence of Black performers elsewhere makes this startling; it’s suggested on the disk’s commentary track that this may not be a peculiar instance of tokenism, but may well have been Whiteman’s only option for bringing in an awareness of what was otherwise absent from the film … even hyper-sensitive censors couldn’t possibly object to the presence of this charming child.

The next number is a solo performance by Willie Hall, a genuine bit of vaudeville in which he plays the violin with virtuosity and some surprisingly dexterous trickery – which involves playing behind his back, under his leg, holding the bow rigid and running the instrument up and down it. He also adds an element of physical comedy with a pair of extra long rigid shoes which allow him to lean and float in seemingly gravity-defying ways.

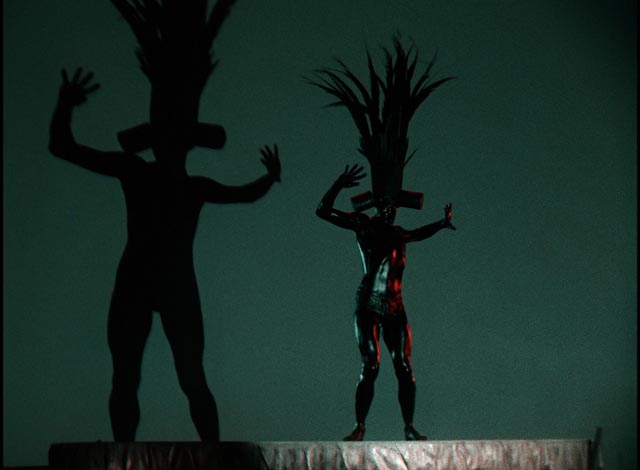

This is followed by three of the film’s highlights, beginning with a condensed version of George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” (which had originally been commissioned by Whiteman for a performance in 1924). This begins with one of film’s oddest oblique references to the Black origins of jazz as emcee Charles Irwin once again evokes Africa and the number opens with a visually striking bit in which a gleamingly black figure performs a dance on top of a giant drum. This “voodoo” number is actually performed by white dancer Jacques Cartier covered in full-body black makeup, simultaneously evoking and erasing racial authenticity.

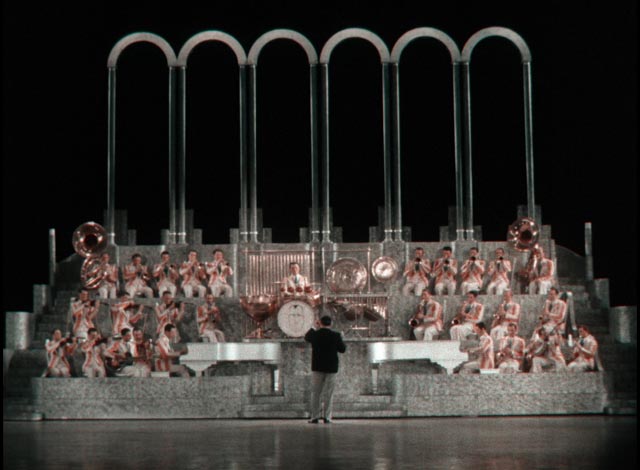

The performance of “Rhapsody in Blue” itself is one of the highlights of Anderson’s elaborate staging, with the band rising up from inside a giant piano and dancers moving up ramps and across bridges in the foreground. It is during this number that we get our first good look at The Sisters G (Eleanor and Karla Gutöhrlein), a pair of singer-dancers from Berlin who introduce a distinct Weimar ambience to the proceedings, although here they remain statically posed in the background. Apparently often mistaken for twins, they do look identical in their black Louise Brooks bobs.

“Rhapsody in Blue”, the symphonic highlight of the film, is followed by another vaudeville turn, introduced in song by Jeanie Lang and George Chiles. “My Ragamuffin Romeo” is an impressive physical performance by dancers Marion Stadler and Don Rose, in which a man pins some scraps of multicoloured cloth to a wall, where they come to life as a living doll which flops in seemingly impossible ways as he tosses her around the stage. The effect is quite remarkable, though you can’t help wondering about what physical damage might result from repeat performances.

The next number is also the film’s most exuberant. “Happy Feet” is another ensemble piece which begins with a bit of stop motion, giving life to a pair of shoes, as The Rhythm Boys launch into the catchy song. In yet another display of the strange possibilities of which the human body is capable, dancer Al Norman performs a “rubber legs” number in which it appears those legs are completely boneless … in fact, he looks just like those rubbery cartoon characters in Walter Lantz’s animated prologue. As if that weren’t enough to make the number distinctive, we then get a duet from the Sisters G in which they appear as a pair of disembodied heads inside a mirror box, singing in both English and German, suggesting the origins of the enticingly seedy nightclub in Kander and Ebb’s Cabaret.

The final three numbers seem somewhat anticlimactic after this. “Nellie” is a throwback to the 1890s music hall, with a barbershop quartet singing about a girl who has disappeared into the fleshpots of the big city. And then there’s what was intended to be Bing Crosby’s big number, “Song of the Dawn”; as it turned out, it was perhaps best that he lost the opportunity because it would be hard to imagine him dressed as a gaucho in a big production number which seems to take place in a barn, with the doors opening to reveal the rising sun at the end.

Although the final number of the film is one of the biggest and most elaborate (it runs almost fifteen minutes), it seems somewhat ponderous after the effervescent energy of “Happy Feet”. “The Melting Pot of Music”, based on something Anderson had previously directed on stage, is an odd visualization of that American myth of “the melting pot”, the idea that the nation had been created by blending elements from many different sources. In the number this is literalized, as we get various national groups performing stereotypical songs, then descending into a vast steaming pot. Once all groups have been added to the mix, Whiteman himself leans into the pot and stirs the ingredients in an image which echoes Murnau and Lang, with everyone eventually emerging as homogenized Americans (in silver cowboy outfits!).

What makes this conceit really problematic is what it omits. The idea that the States are a land of possibilities and new beginnings for all the peoples of the world is undercut by the fact that all we see are white Europeans. That homogenized nation has no room for “others” … no Asians, no Native Americans, and perhaps most strikingly since the number is a metaphor for the creation of the distinctive musical form known as jazz, no Africans …

While it’s no doubt unfair to expect an elaborate souffle like King of Jazz to address the complex issues of race which are woven through American history and culture, its emphasis on this music makes it impossible not to be aware of what has been elided from this musical history. But those reservations aside, the movie is not merely entertaining – it’s a fascinating piece of film and music history, and Paul Whiteman himself possesses a great deal of affable charm.

*

In between all the musical numbers, the film is punctuated by brief comic “blackouts”, a device imported from vaudeville. These feature drunkenness and infidelity and a sexual suggestiveness which would probably have been banned just three years later by the Hays Office.

*

The disk

The 4K restoration by Universal, although inevitably of uneven quality, is quite spectacular, with the colours often breathtakingly rich. The restoration isn’t quite complete, with several of Irwin’s introductions represented by stills and what remains of the audio, but the visual quality sustains interest even if not all the performances are equally engaging. What is undeniable is that the film’s huge budget all shows up on screen. The soundtrack, despite the technical limitations of the time, serves the music quite well.

The supplements

Criterion have loaded the disk with excellent supportive material, beginning with a lively and informative commentary from music experts Gary Giddins, Gene Seymour and Vince Giordano. Together they supply a great deal of background, with an emphasis on the musicians in Whiteman’s band and the context in which he had become so successful.

Giddins (16:50) and Michael Feinstein (19:14) expand on the issues of race and musical appropriation in separate interviews, and James Layton and David Pierce (authors of a book about the making of King of Jazz) provide four video essays about aspects of the production (total 44:20), plus a gallery of pages from the musical score.

There are three additional comic blackouts which were included in the 1933 re-release (totaling 2:24), which also push the limits of Hays Office censorship with explicit references to premarital sex and illegitimate birth, and a visual pun about a horse’s ass. There are also revised titles from the re-release (2:05).

There are two shorts, the first a version of Anderson’s “The Melting Pot of Music” called All Americans (1929), directed by Joseph Santley; the second I Know Everybody and Everybody’s Racket (1933), based on an idea by Mark Hellinger and featuring Walter Winchell as himself introducing a country girl to New York nightlife in a club where Paul Whiteman and his band are performing.

And finally there are two Oswald the Lucky Rabbit shorts from 1930, both related to King of Jazz: Africa is a reworking of the feature’s prologue with Oswald replacing Paul Whiteman on safari, while My Pal Paul has the rabbit encountering the band leader.

The booklet essay is by Farran Smith Nehme.

Comments

Enjoyed this film but was disappointed I could not find pictures of some of the players or biography’s on Wikipedia? Was bit confused at Whiteman’s ‘double’? Was it Whiteman dancing or a double? Couple who did ‘I like the things you do’ and Voodoo dance are addictive. No pictures of these people?