Rhyming Pairs

By coincidence rather than design, my recent viewing has included what you might call several rhyming pairs – three sets of two movies, each of which reflects and illuminates the other in some way. These include a pair of Animes from 2016, two thrillers by English directors from the late-’60s and early-’70s, and the first two features by an aggressively independent director from New York made at the tail end of the ’70s.

Your Name (2016) & In This Corner of the World (2016)

Japanese animation has always been distinct from the western/American variety, at least partly due to its roots in Manga, an equally distinct Japanese form of graphic storytelling which is targeted more towards adults than children. In contrast to the familiar Disney-dominated forms of animation, Manga and Anime not only often lean towards violence and sex, but also feature complex approaches to theme and narrative. Even those works which might be viewed as “children’s films” (the works of Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli) are frequently darker and more complex than their western equivalents – closer to the darkness of traditional fairy tales than the sanitized Disney versions.

But for all the epic fantasy and science fiction which dominates Anime, one of the most interesting aspects of the form are those films which might just as easily have been made with live action – subtle, realistic character studies like Isao Takahata’s Only Yesterday, Hayao Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises, Goro Miyazaki’s From Up On Poppy Hill, Keiichi Hara’s Miss Hokusai.

Sunao Katabuchi’s In This Corner of the World (2016) belongs to this group, a detailed depiction of a real place and time, with a focus on ordinary lives. In this case, the film tells a naturalistic story of a young woman from Hiroshima who accedes to an arranged marriage and moves to live with her husband’s family in the nearby port of Kure. While the film keeps its focus close on her experience of adjustment, the hard work she must submit to as something of a live-in servant whose only real outlet is her love of drawing, for the viewer the larger context of the war and the eventual inevitable dropping of the Bomb on Hiroshima infuses everything with an air of fragility and melancholy.

Katabuchi performs a delicate balancing act. The sheer mundane ordinariness of the life depicted risks audience boredom with its single-minded attention to trivial details – and the limitations of the pictorial style, with its simplified facial features, gives us only limited access to the inner lives of the characters (something like what you might get if Ozu had constrained his characters with kabuki make-up). The director trusts that our knowledge of what is coming will provide the deeper emotional resonances. This is not a phantasmagoric depiction of the incomprehensible horror of war like Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies (1988), but rather a contemplation of resilience and survival. As a result, its impact seems less powerful and its pleasures remain those of small details well observed.

Makoto Shinkai’s Your Name (2016) also deals with ordinary lives caught in the shadow of catastrophe, but here historical realism is replaced by fantasy on an epic scale. We are introduced to two characters living in different places, both high school students. Mitsuha lives in a small mountain town, where her father is the mayor; Taki lives in Tokyo, balancing school with a part-time job and dreams of becoming an architect. One day, these two find themselves inexplicably trading places, inhabiting each other’s bodies for a day.

Initially this situation provides opportunities for comic confusion; each has to figure out where they are and how they relate to the people around them. This involvement in each other’s lives begins to subtly change those relationships and how friends and family view the two kids. But as the switching is repeated over and over again, they begin to leave notes for each other and a strange long-distance relationship develops with intimations of a growing affection.

But with each switch larger issues begin to emerge. It becomes apparent that their connection spans not merely physical space but also time, and their bond foreshadows a catastrophic cosmic event which threatens Mitsuha’s town; somehow together they have to find a way of averting the disaster. Once again, the fragility of individual lives in the face of destructive events becomes the subject … but here the unfolding of the complex plot supports a more powerful emotional response to the characters’ situation. Paradoxically, the fantastic catastrophe here seems to have more impact than the historic disaster of Katabuchi’s film, partially because the characters themselves eventually know what’s coming and have a degree of agency in trying to affect the outcome.

Not only is Your Name a complex and imaginative fantasy, it’s also a deeply moving human story which takes full advantage of the possibilities inherent in Anime.

*

Point Blank (1967) & Pulp (1972)

In 1967, John Boorman had several years of documentary television experience and just one feature to his credit – Catch Us If You Can (1965), a vehicle for a popular English band, The Dave Clark Five (written by Peter Nichols, best known for Georgy Girl, The National Health and A Day In the Death of Joe Egg). But somehow in 1967, at age 34, Boorman found himself in the States directing a thriller with a major star. This was a period when the influence of European cinema, particularly the French New Wave, was helping to break down the traditions of Hollywood studio filmmaking and Point Blank (based on the novel The Hunter by Donald E. Westlake, writing as Richard Stark) has a tricky, elliptical narrative trajectory which even a few years earlier probably wouldn’t have got past the studio powers. Yet it received a major release from MGM.

The story, beginning and ending on Alcatraz just a few years after the prison was decommissioned, starts with protagonist Walker (Lee Marvin) finding himself betrayed, shot and left for dead by a man he was helping to intercept a mob money drop. Not, though. just by this friend, Mal Reese (John Vernon, Dirty Harry’s future mayor of San Francisco, in his first U.S. feature); he’s also betrayed by his wife Lynne (Sharon Acker), who has switched allegiance to Mal. As Walker lies in a filthy cell, apparently dying, a series of quick, jarring edits disrupts the narrative flow and we meet him on the deck of a tour boat off the island, talking to Yost (Keenan Wynn), seemingly a federal agent who is trying to enlist Walker in a plan to bring down a powerful criminal gang. All Walker is interested in is reclaiming his share of the money from that opening robbery, $93,000.

Walker gradually works his way up through the organization, first tracking down Lynne, who has already been ditched by Reese. Reese himself is a low level part of the organization, with little protection or support from his bosses, who simply want Walker put out of the way. As the bodies begin to pile up and Walker miraculously escapes attempts on his life, the refusal of everyone to simply give him the $93,000 eventually destroys the gang, leaving all the bosses dead and the true identity of Yost revealed in the final moments. The film ends enigmatically with Walker fading back into the shadows of Fort Point, beneath the Golden Gate Bridge with Alcatraz visible across the water in the distance.

The ending leaves open the possibility that Walker may actually still be in that cell back at the beginning, the whole story being a phantasmagoric dream of revenge at the moment of death; or alternatively, that he’s a kind of avenging ghost wreaking destruction on all those who betrayed him. Whatever the case, Point Blank refuses the kind of by-the-numbers narrative clarity audiences would have expected of a mob thriller at the time, looking forward to the uncertainties which began to dominate in the early ’70s.

Narrative unreliability is one of the key points of Mike Hodges’ Pulp (1972), the follow-up to his genre-defining first feature Get Carter (1971). Although Pulp reunited writer-director Hodges with star Michael Caine and producer Michael Klinger, it flopped at the box office and pretty much disappeared for the next four-plus decades. Audiences and critics whose expectations had been set by Get Carter were confused, frustrated and disappointed. What Hodges gave them was a self-reflexive B-movie thriller which played more for comedy than grim thrills.

With time and distance, Pulp looks more interesting, though whether it actually works even on its own terms is up for debate. Caine plays Mickey King, author of paperback thrillers under numerous pseudonyms, who finds himself drawn into a mystery on a Mediterranean island (the film was shot on Malta, though originally planned for Italy) when he’s approached by an agent (played by the inimitable Lionel Stander) for some unnamed person who wants a ghostwriter for his autobiography. As King travels to meet his client, he encounters a number of suspicious people, one of whom turns up dead in the bathtub of the hotel room King was supposed to occupy.

The client turns out to be Preston Gilbert (Mickey Rooney), a fading Hollywood star with mob connections, now apparently targeted by a hitman because he knows a secret which former associates believe he’s going to reveal to the writer. There are further deaths before that secret is exposed, but in the end there’s nothing King can do with the knowledge – he’s powerless in the face of a privileged class which can act outside the law with impunity.

The first notable thing about Pulp is that in many ways it reiterates the core narrative of Get Carter. Caine as King journeys to another place where he finds himself investigating a brutal crime committed against a young girl – in the previous film, his niece; here a village girl used and abused and left for dead by the members of an exclusive hunting club. As in the previous film, the protagonist’s investigation leads to a number of deaths and the ultimate realization that he’s powerless to change the system which permitted the crime to be committed in the first place. Some of the bad people end up dead, but the system remains.

The second notable thing is the completely different tone here. Instead of Carter’s grim northern realism, Pulp is set in a sunlit fantasy place where people behave like characters in a movie. This is at least partly due to the fact that we enter this world through the consciousness of an entirely unreliable narrator. There is a constant tension between what we see and what we are told about it in voiceover by King, who tells the story as if it’s one of his own potboiler novels. He manages to transform a brutal crime into a pulp narrative, this transformation itself adding to his inability to affect events in any meaningful way. There is reality, and then there is what we do with that reality as we turn it into a story we tell ourselves in order to make sense of events. King’s failure is due to the poverty of his own narrative imagination.

Pulp is directed by Hodges’ with as much skill and polish as Get Carter, but the distancing effect of its approach to the story keeps the viewer from engaging fully with the characters and situations; we are instead asked to stand back and interpret the story from a thematic perspective, rather than immerse ourselves in the narrative. This makes it an interesting film, full of imaginative visual details, but a less immediately satisfying experience. It may ultimately just be a matter of personal taste, but the more deliberately comedic tone makes Pulp less engaging for me than, say, Badlands, the film made by Terrence Malick the following year which uses a similar kind of dislocation between events and a character’s interpretation of those events.

*

The Driller Killer (1979) & Ms. 45 (1981)

Abel Ferrara sometimes reminds me of Sam Fuller. There’s a blunt force to much of his work, although Ferrara, unlike Fuller, is willing to be consciously artful at times. He often draws on B-movie genre forms, but like Fuller he resists being bound by them. Like Fuller, he seems to enjoy bending, or even breaking, viewer expectations. He’s made gangster films (King of New York, The Funeral), science fiction (Body Snatchers, New Rose Hotel), a modern reworking of the vampire myth (The Addiction), self-reflexive movies about movies (Dangerous Game, The Blackout), and perhaps most famously, he out-Scorsesed Scorsese with his searing Catholic-pervert-cop-and-raped-nun fever dream Bad Lieutenant. Here, his affinity with Fuller is most apparent – the willingness to overheat his material until it ignites, his glee in pushing the boundaries of taste to the breaking point in order to dig beneath the polite surface of social decorum to expose the worst tendencies of people while also suggesting that there actually is a possibility of redemption.

This deliberate “tastelessness’ was there right from the start of his career (though I haven’t seen his pseudonymous first feature, the pornographic Nine Lives of a Wet Pussy, I assume this point holds true there). I just re-watched his first two signed features, a pair of urban exploitation nightmares steeped in madness and violence triggered by life on the economic fringes of New York City in its grungy pre-Giuliani heyday.

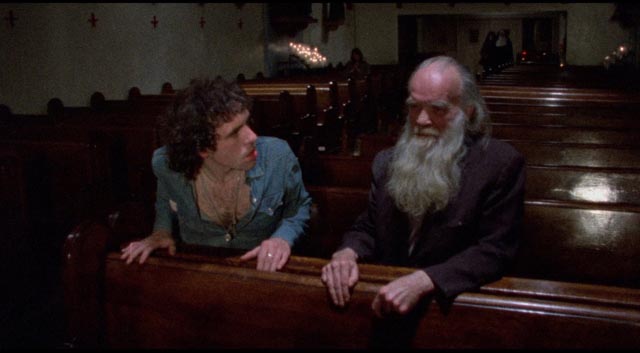

The Driller Killer (1979) was prosecuted in Britain during the “video nasties” panic of the early ’80s and as much as any other movie exposes the absurdity of that time. Although it does contain some graphic violence, it’s portrayed in such an extreme and absurdist style that the intent is obviously satirical. This violence is an expression of the economic and social panic which overwhelms an artist living in a rundown area of the city with his girlfriend and another woman. The film opens with him going through a stack of unpaid bills, firing accusations at the two women for their profligacy although most of the household income comes from the girlfriend while he struggles to finish his “masterpiece”, which he anticipates will bring him a lot of money from a gallery dealer along with the security success will guarantee.

The artist, Reno (played by Ferrara himself under the nom-de-screen Jimmy Laine), is consumed both by a feverish creativity and a nightmarish anxiety triggered by the omnipresence of homeless derelicts in the streets around the building in which he lives in the Union Square neighbourhood. As things continue to slide downhill and destitution looks more and more possible, he fantasizes about inflicting violence on these bums as if he can forestall his own decline by eliminating them. When the art dealer heaps contempt on the finished painting, the dream of wealth evaporates and Reno goes on a rampage, armed with a power drill and a portable battery belt. His attacks are random and pointless, a spontaneous response to the spectre of failure.

All of this is treated with dark humour and an attentive eye to the grungy realities of living on the edge; Reno’s relationship with his girlfriend Carol (Carolyn Marz) can’t survive the economic strain and she chooses to go back to the middle class life she had abandoned in order to be with him … leading to a dark ending.

The Driller Killer is a raw, frequently crude movie, but one of its strengths is its documentary value as a portrait of late ’70s New York as a grimy, insecure city. The depiction of Reno’s life and the streets he walks down has an air of reality which is far more chilling than the over-the-top power-tool violence. Equally interesting are the musical interludes with a punk band who move into the building and add to Reno’s torment with their round-the-clock rehearsals. The situation is aggravated by the fact that Reno and Carol’s roommate Pamela (Baybi Day) recommended that the band move in. The scenes of the band, Tony Coca-Cola and the Roosters, in rehearsal and playing a club, reminded me of Andy Warhol’s The Velvet Underground and Nico (1966), with their raw energy and the feeling that things could explode into chaos at any moment.

Despite the low budget and the grimy milieu which suggest lower rung exploitation, The Driller Killer is a serious movie made with fierce energy and thematic purpose which captures the flavour of a particular time and place.

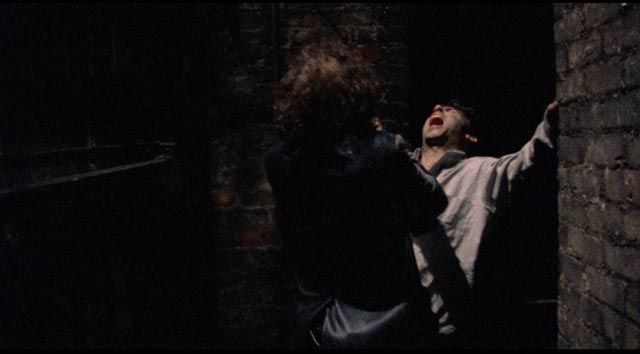

The same can be said of Ferrara’s next feature, Ms. 45 (1981), although this – the quintessential rape-revenge movie – is a big leap forward technically and creatively. Once again shot vividly on location, it’s a darker, more serious film, given sharper focus by an intense performance by Zoë Tamerlis as Thana (an almost too-obviously-loaded name), a mute garment worker in a small fashion house. Quiet and shy, her voicelessness isolates her from her co-workers and leaves her apparently fragile and defenceless. Walking home one day after work, a masked man (Ferrara again as Jimmy Laine) drags her into an alley and rapes her. She manages to make her way home, only to find an intruder who also attacks her. But this time, during the rape, she manages to crack the guy’s skull with a heavy object.

Traumatized, Thana drags the body into the bathroom and proceeds to cut it into pieces which she wraps in butcher paper and stuffs into her fridge. Through the rest of the movie, she gradually takes these pieces and drops them at various places around the neighbourhood. She also gains strength and determination from possession of the intruder’s gun (the .45 of the title); she changes her appearance, becomes more assured as she makes up and dresses herself in a deliberate representation of female sexuality as defined by the commercialized society she lives and works in. In this new assumed persona, Thana goes out at night, deliberately attracting the attention of men whom she guns down when they close in on her.

While her reaction to the original assaults is understandable, the power which has been unleashed gradually consumes her; every man is eventually perceived as a threat and her vengeance becomes relentless, striking not only at strangers, but also at her boss and co-workers. Ms. 45 is a bleak depiction of what seems an implacable conflict between the sexes; Thana’s muteness represents the submissiveness a woman is required to show towards male power … when she seizes the intruder’s gun, she claims that power for herself and turns it back on her oppressors. Her revenge is ultimately a self-destructive dead end, and the film concludes on a chilling note – it’s another woman, herself assuming phallic power, who ends Thana’s rampage, at least temporarily restoring the gendered status quo.

In The Driller Killer, Reno’s violence is an absurdist response to economic anxiety; in Ms. 45, Thana’s violence is an existential response to an unbearable situation which is rooted in the role assigned to her by an oppressive society. In both cases, though, Ferrara uses the tropes of exploitation to serve his more serious purpose, as he would continue to do in many of his later films.

*

Disk details

Both In This Corner of the World and Your Name look terrific on Blu-ray, the former from Shout Factory, the latter from Funimation. The World disk includes interviews with director Sunao Katabuchi and producer Masao Maruyama in addition to a featurette comparing present-day Hiroshima and Kure to what they were during the war. The Your Name disk includes an interview with director Makoto Shinkai, a filmography illustrated with clips from Shinkai’s work, and a made-for-TV making-of.

The Warner Blu-ray of Point Blank has no new extras, but includes those from the earlier DVD edition – a commentary with John Boorman in conversation with Steven Soderbergh, and a couple of archival featurettes about the shoot. Although the DVD was pretty decent, both picture and sound are improved on the hi-def disk.

Arrow’s Pulp Blu-ray features a 2K restoration which gives a film-like image, with clear mono sound. There are four new interviews totaling almost forty minutes: director Mike Hodges, cinematographer Ousama Rawi, assistant director John Glen and Tony Klinger, son of producer Michael Klinger. The booklet contains an essay by critic Alexandra Heller-Nicholas and a piece about the making of the film by Mike Hodges.

The two Ferrara features are presented in hi-def restorations, both of which present a film-like image and make the best of the low-budget material. Arrow’s edition of The Driller Killer offers two different cuts: the theatrical version and a pre-release cut which has an extra five minutes originally trimmed by Ferrara before release. These range from individual shots to a couple of complete scenes. Both cuts are additionally presented full-frame (1.37:1) and widescreen (1.85:1). There’s a new commentary by Ferrara moderated by Brad Stevens, an interview with Ferrara, a visual essay by Alexandra Heller-Nicholas which surveys Ferrara’s career, and most significantly Ferrara’s 2010 documentary feature Mulberry St., shot on the Lower East Side during the Feast of San Gennaro; this is a raucous, crowded, profane portrait of the Italian community which has played a significant role in his work.

The Drafthouse Blu-ray of Ms. 45 includes three interviews totaling almost half-an-hour: Ferrara, composer Joe Delia and creative consultant Jack McIntyre. In addition there are two brief featurettes by Paul Rachman about star Zoë Tamerlis, whose life was short but intense. There’s also a booklet with essays by Tamerlis, Brad Stevens and Kier-la Janisse.

Comments