Sinatra x 2

Frank Sinatra was a star, his celebrity resting on his abilities as a singer. His success and the larger-than-life image he projected made it virtually inevitable that he would get into movies, initially as an extension of his singing career. His obvious screen presence led to bigger roles and a burgeoning dramatic career. But, as with many stars, his celebrity persona would often dominate a movie role; he had obvious acting ability, but much of the time it was Sinatra up there on screen rather than a character fully integrated into a narrative.

This tendency eventually led to the Rat Pack movies – Oceans 11, Sergeants 3, 4 for Texas, Robin and the 7 Hoods – which encouraged a kind of laziness; these movies rested almost entirely on his and his co-stars’ public personae and had the air of buddies just goofing off and amusing themselves in front of the camera. He became notorious for his disinterest on set, wanting to shoot quickly and get the hell away for more partying. This was why, in his later career, he favoured journeyman Gordon Douglas as a director; Douglas was fast and efficient and placed few demands on his star.

And yet, Sinatra was quite capable of giving an impressive, nuanced performance in which he used his imposing presence to the advantage of the movie. I recently re-watched a couple of my favourites from his filmography.

*

Von Ryan’s Express (Mark Robson, 1965)

Mark Robson’s Von Ryan’s Express (1965) was based on an autobiographical novel by David Westheimer, which drew on the author’s own wartime experiences. Westheimer’s realism was inevitably overcome by the needs of a major studio looking for a box office hit in the wake of a major financial disaster – 20th Century Fox, which was reeling from the out-of-control production of Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s Cleopatra (1963). And yet, while the signing of Sinatra to star inevitably pushed the story towards a Hollywood fantasy adventure version of the war, the final result has some interesting and unexpected aspects.

Sinatra is Colonel Joseph L. Ryan, a fighter pilot who crashes in Italy in 1943 as the Allies prepare to extend the invasion of Sicily to the mainland. By this time, the alliance between Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy is collapsing and the pilot is captured by Italians who hide him from the Germans, taking him to an Italian prison camp rather than turning him over. The camp is under command of a petty Mussolini-esque officer named Battaglia (Adolfo Celi), who has cut off food, clothing and water to punish the mostly British prisoners for their continued attempts to escape.

The prisoners’ commander has just died from this punishment, and many of them are suffering from malaria; this reinforces the resolve of the ranking British officer, Major Fincham (Trevor Howard), to continue the escape attempts. Outranked by Ryan, Fincham immediately butts heads with the American. On the surface, this conflict at first seems straightforward: the pragmatic American, conflicted about his role in the war, rejects the Englishman’s rigid military code (rooted in a regimental tradition which goes back hundreds of years), and he betrays the latest tunnel in exchange for concessions from Battaglia – concessions which are quickly reneged on, with Ryan sent to the punishing “hot box” in which the British commander recently died.

While he’s locked up, the Italian regime collapses and the country surrenders, turning the Germans into a hostile occupying power. The camp’s guards disappear and Fincham sets up a field court martial to try (and inevitably condemn) Battaglia. Ryan intervenes, insisting that this amounts to murder of a man who is now a de facto civilian. He persuades the men to throw Battaglia into the hot box himself, drawing an ominous threat from Fincham should the survival of the commandant result in the death of any of the men.

Setting off on foot for the coast, the four-hundred prisoners take shelter in some ancient ruins, only to wake surrounded by Germans … led to them by none other than Battaglia. Ryan’s decency has resulted directly in the deaths of many men and the recapture of the rest. The British take to referring to him as Von Ryan for what they see as his betrayal.

With the prisoners placed in box cars on a train heading towards Germany, it seems that Ryan has made their situation far worse than it had been. Fincham in his anger seethes with blame and contempt, but fatalistically accepts their apparent fate; but Ryan begins to work out a possible way to escape. His plan involves taking control of the train, faking orders from the German High Command, and eventually riding the rails all the way to Switzerland. The mechanics of the plan make for a suspenseful narrative, which is further complicated by Ryan’s continuing insistence on behaving decently rather than with pragmatic brutality. Again, his unwillingness to commit to the imperatives of war costs lives.

Sinatra’s commitment to the role led to a major clash with the studio; he insisted that Ryan must pay with his life in the end, atoning for the errors which cost other people’s lives. Although by the mid-’60s films about World War Two were more often than not little more than adventure movies, lacking the moral ambiguity which characterized a lot of post-war movies, which had grown more introspective than the frequently one-dimensional morale-boosting propaganda made during the war, Von Ryan’s Express does manage to complicate what on the surface is a straightforward action story. The no-nonsense attitude of Ryan when he arrives and upends the life of the prisoners – who had become unproductively mired in a stubborn adherence to an ingrained sense of duty which ignores the reality which is slowly killing them – seems initially like the brash, unencumbered, forward-looking image of America confronting a fading old world. But as things unfold, Ryan’s attitude begins to look like naivety, while the apparently rigid forms of tradition which guide Fincham start to look practical in the circumstances. It’s Fincham who begins to look like the pragmatist, while Ryan is fatally hampered by a misplaced idealism. The truth is they both need each other to accomplish what has to be done; each on his own is flawed and potentially self-destructive. The movie ends up much darker than it starts out, and to a large degree this is due to Sinatra’s willingness to deprive Ryan of any ultimate heroism.

The 2012 20th Century Fox Blu-ray has a decent if grainy transfer and includes four brief featurettes about the production, war films in general and Jerry Goldsmith’s score. There’s also a combined isolated score and commentary track with Nick Redman, John Burlingame and Lem Dobbs.

*

The Manchurian Candidate (John Frankenheimer, 1962)

While Von Ryan’s Express manages to add a few interesting layers to its familiar narrative, it’s essentially a conventional studio movie made by a sturdy, journeyman director; The Manchurian Candidate (1962) on the other hand pushes the boundaries of traditional Hollywood filmmaking. John Frankenheimer, here directing only his fifth feature, had already made audacious experiments with style, technique and tone in a remarkably busy television career which produced almost six-dozen plays, movies and series episodes in just five-and-a-half years. Based on Richard Condon’s cold-war satirical thriller, The Manchurian Candidate is still an unsettling experience fifty-six years after its original release. The almost avant-garde play with audience perception through radical photography (by Lionel Lindon, an accomplished but hitherto conventional technician) and disorienting editing (by Ferris Webster, a major figure who spent the last ten years of his long career working exclusively for Clint Eastwood) makes it almost impossible to pin down the film’s meaning with the kind of easy clarity Hollywood had worked so hard to perfect over the preceding decades.

The Manchurian Candidate is a cold war thriller which simultaneously exploits and satirizes the Red Scare paranoia which drove the United States politically insane from the late ’40s to the ’60s. It begins by elaborating – to a Baroque degree – the fear of communist brainwashing which reached its height during the Korean War, then segues into a savage satire of McCarthyism, then digs deeper by revealing that toxic political movement as itself a tool of the Communists for undermining the stability of the U.S. government and society, before plunging terminally into a nightmare rooted in “momism”. This last was a concept put forward by author Philip Wylie in his 1942 book A Generation of Vipers, which warned that the nation was endangered by the power of women to dominate and emasculate men, specifically in the figure of the mother who refuses to relinquish control of her sons.

The film’s position on the Cold War conflict between democracy and communism shifts repeatedly but in the end seems to settle on a rather conservative warning that the Reds pose a very real danger to democracy’s survival. But by then, the psychological threat has overpowered the political one; what is most imperative is the destruction of the smothering feminine, freeing men up to assert their authority and face the demands of the Cold War from a position of psychological clarity and strength. As should be clear by now, I find the film an enthralling entertainment, but remain ambivalent about what it’s really trying to say through its thriller trappings and satirical tone.

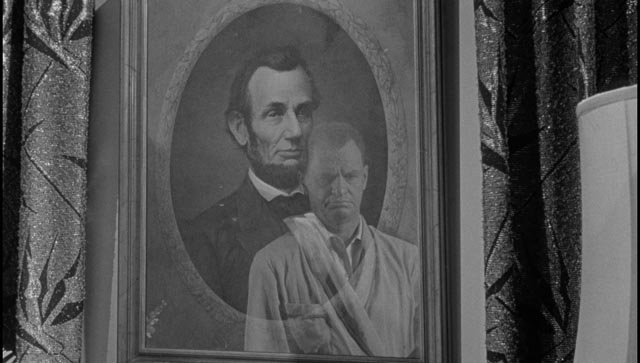

It begins in Korea in 1952, with an American patrol betrayed by their Korean interpreter, seized by a combination of Russian and Chinese forces and flown to Manchuria where over a period of three days they are brainwashed by an amusingly cartoonish array of villainous enemy military scientists (from the Pavlov Institute). This provides the film’s most stylistically audacious sequences as the now will-less soldiers sit placidly in what initially appears to be a New England hotel lobby where they listen, bored, to a presentation by members of a ladies’ horticultural society. Frankenheimer’s camera pans slowly and relentlessly around the room, eventually circling back to its starting point where we now see an amphitheatre with rows of doctors and military officers looking down on a stage where the soldiers sit just as placidly in a row as Dr. Yen Lo (Khigh Dhiegh) demonstrates the effects of his radical conditioning techniques. He has the unit’s staff sergeant, Raymond Shaw (Laurence Harvey), first garrote one man, then shoot the youngest in the head. Under the influence of the conditioning, Shaw is completely obedient, all self-consciousness suppressed, while the other men have no reaction to what they see.

Back in the States, Shaw is greeted as a hero, awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for bravery in saving all but two members of his unit. The other men, when asked for their opinion of Shaw – an officer they originally all despised as weak and rule-bound – repeat a paean to his wonderful qualities in a disturbingly robotic manner. But when asleep, they begin to have nightmares in which they see Shaw killing their two comrades. We first meet the film’s protagonist, Major Bennett Marco (Frank Sinatra), as he wakes in terror from such a dream. When he reports this recurring nightmare to his superiors, they temporarily remove him from his intelligence duties, assigning him to a PR role, where he first encounters Senator Johnny Iselin (James Gregory), a grandstanding buffoon modelled on Joe McCarthy, as he interrupts a committee hearing by yelling out that he has a list of known communists in the government. That list becomes something of a running gag as Johnny can’t settle on an actual number until his wife, watching him dump ketchup on his dinner, sees the Heinz motto and tells him to stick with 57.

Iselin’s wife Eleanor (Angela Lansbury) also happens to be Raymond’s mother. She is working hard behind the scenes to engineer Johnny’s nomination for vice president at the upcoming party convention and Raymond’s war heroism is one of the tools she exploits to that purpose. But Raymond is disgusted by Johnny and makes an effort to break away from his mother, taking a job in New York as an assistant to a left wing columnist. In the lead-up to the convention, Raymond is taken into a private clinic under the pretext of a fake accident so that Dr. Yen Lo and other communist agents can fine-tune his conditioning. In a trial run, he is sent to murder his boss; having proven the effectiveness of their control over him, the film gives us its biggest plot reveal at a party thrown by his mother. She herself turns out to be his primary handler; she had needed an assassin to further her plans for Johnny (the rabid anti-communist who is in fact a communist tool in a plot to undermine the government); she was surprised, and she suggests saddened, that they weaponized her own son. But not enough to derail the plan. She knows that the intention was to bind her more closely to her foreign masters, but it has rather determined her to push ahead with her own plans for control of the country.

The queasy core of the narrative is this sick relationship between Raymond and Eleanor. Crushed from the start, Raymond has been unable to forge a stable and healthy personality – as he tells Marco, he knows that he’s not “lovable”. He’s a weak, resentful, self-pitying figure whose one chance to break free and find himself is a relationship with Jocelyn (Leslie Parrish), the daughter of Iselin’s political opponent Senator Jordan (John McGiver). Raymond manages to assert himself sufficiently to sneak away and marry Jocelyn; this leads to the film’s most distressing and tragic moment as Eleanor uses his conditioning to kill both the Senator and Jocelyn. The mother, in her need for complete control over her son, coldly destroys him.

While all of this is unfolding and the convention draws near, Marco has convinced his superiors that something sinister is going on with Raymond at the centre and he’s been assigned to investigate. He befriends Raymond and gradually uncovers the method by which he’s being controlled (it involves a pack of cards and particularly the Queen of Diamonds); with the conditioning weakened by the loss of Jocelyn, Marco manages to break it. But Raymond, given back his own damaged self, has nothing left to live for and he evades Marco on the night of the convention when he’s supposed to assassinate the newly nominated candidate for president, thus propelling Johnny to the top spot. There’s only one way Raymond can free himself and he turns the plan against its architects.

This is the political satire thread of the narrative, but there’s a parallel line which follows Marco’s investigation. Beginning with his distressing nightmares, his ineffectual assignment to the PR role, and finally regaining a sense of agency as he closes in on the plot to use Raymond as an assassin, this line reinforces with more subtlety the main theme of emasculation. Marco is plagued by a sense that he has only tenuous control over himself, his memory, his feelings. He’s unstable and fearful. In one of the finest sequences in all of Frankenheimer’s work, Marco struggles in the club car of a train to light a cigarette, his hands shaking uncontrollably, breaking out into a sweat before he rushes out to the corridor. All of this has been observed by a woman sitting across from him. She follows him out, lights a cigarette and hands it to him. This is Eugenie Rose Chaney (Janet Leigh); obviously drawn by his distress, she initiates a conversation built on strange non-sequiturs which becomes both funny and disturbing in its almost surreally poetic disconnection from the normal requirements of dramatic dialogue.

While in conventional terms this is a meet-cute which leads to a romantic relationship, there’s actually something else going on. Rose is drawn to Marco by overt signs of psychological distress, for which she offers some kind of comfort. She takes control in that first encounter, the romantic entwined with a maternal concern. Their relationship comes to mirror the unwholesome ties between Raymond and his mother, reinforcing the idea that men are in serious danger of emasculation by dominant women (the brief relationship between Raymond and Jocelyn is more equal and supportive, but it’s quickly destroyed by Eleanor, who refuses to relinquish her control).

So what is the film saying? That the U.S. is particularly vulnerable to communist efforts to undermine democracy because male authority is undermined by the power of dominant women? Is it in fact misogynist at its core? I’m reminded of the way the Department of Defence revised John Huston’s powerful postwar documentary Let There Be Light (1946). Huston’s original version offered an empathetic and supportive approach to the psychological problems faced by servicemen returning from World War Two, but this was suppressed and replaced by a version which attributed that psychological damage to pre-existing weaknesses instilled in certain men by overly protective mothers. There, and implied in The Manchurian Candidate, men are being warned to resist strong and independent women because they take power away from the men they dominate. Monstrous mothers (and romantic partners) are a bigger threat than communism itself.

These thematic issues remain ambiguous and unsettling in The Manchurian Candidate, but the film itself is a work of virtuosic power, one of Frankenheimer’s most accomplished movies. It also represents some of the best work ever done by the cast, from Angela Lansbury’s monstrous mother to Janet Leigh’s predatory charmer, from Laurence Harvey’s tormented weakling to Sinatra’s protagonist who struggles mightily to overcome weaknesses imposed by external forces. The star was never better than here, and it’s interesting to see how willingly he displays Marco’s vulnerability, immersing himself in the narrative rather than trying to dominate it. There’s no sign here of the smug and lazy performer who barely phoned it in for movies like Tony Rome and Lady In Cement just a few years later.

Criterion’s 2016 Blu-ray is mastered from a 4K restoration, with film-like grain and strong contrast. The disk includes Frankenheimer’s commentary from 1997 and a 1987 featurette from previous editions: a brief conversation between Frankenheimer, Sinatra and screenwriter George Axelrod. There are several extras new to this edition: an interview with Angela Lansbury, an appreciation by Errol Morris, and an interview with historian Susan Carruthers about the Cold War fear of brainwashing. There’s also a trailer and a booklet essay by critic Howard Hampton.

Comments