Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cure (1997)

Cure (1997) was my first exposure to the work of Kiyoshi Kurosawa. I saw it at the Toronto International Film Festival in 1998. The catalogue description was intriguing – and slightly teasing – but the actual experience of watching the film proved frustrating. Although it belonged to a familiar genre (police investigate a series of brutal killings which, despite their similarities, seem to be completely unconnected), it aggressively refused to provide narrative clarity. In fact, it remained so enigmatic that it felt like an assault on the audience by a director at war with commercial conventions.

The next Kurosawa film I saw was Kairo (Pulse, 2001), which is also elliptical and enigmatic, but in its disturbing evocation of a not-quite-comprehensible apocalypse it provided more familiar genre satisfactions. Although Kurosawa has been quite prolific (some twenty features and TV movies in the past twenty years), I’ve only seen a couple of others, partly because of that refusal to provide some kind of narrative clarity … which I freely admit is more a weakness on my part than a supportable criticism of Kurosawa as a filmmaker. He is obviously determined to challenge an audience which clings to certain expectations.

Kurosawa had been making movies for two decades before writing and directing Cure, but this was his international breakthrough. His previous work had mostly been in the “pink film” and yakuza genres, much of it direct-to-video (in Japan known as V-cinema). The relative success of Cure was partly due to the groundwork laid by Jonathan Demme’s Silence of the Lambs (1991) and David Fincher’s Se7en (1995), which had firmly established the serial killer movie in popular culture – but those movies and the many lesser examples they spawned, no matter how enigmatic they tried to be, always returned to some kind of clear narrative resolution, providing closure for the audience no matter how bleak it might be. Cure thumbs its nose at such considerations.

Watching Kurosawa’s movie again on the new Masters of Cinema Blu-ray, prepared to be sophisticated and ready to take some kind of meta-cinematic stance which would provide intellectual distance, I found all of my original disorientation and frustration flooding back in. Kurosawa skilfully drew me into his labyrinth once again and left me dangling without the kind of resolution which allows one to withdraw from a horror movie with a sense of satisfaction, released from dark events back into the real world sated but essentially untouched. As the end credits rolled, I was left with the same squirmy “what the fuck?” feeling I’d experienced at TIFF twenty years ago.

Kim Newman, in an interview on the disk, and Tom Mes in his booklet essay, not to mention Kurosawa himself in two interviews (one archival, one new), all stress that this is exactly the intention of the movie. Kurosawa has no interest in providing answers, only in provoking the audience to seek answers within themselves to the questions the film raises … the most significant being the relentlessly repeated “who are you?” which becomes the central refrain of the “killer”.

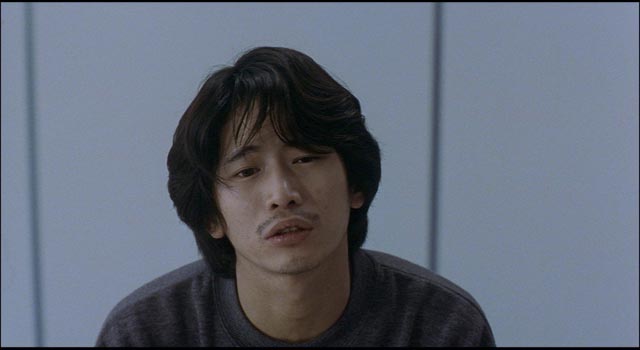

I have to use the quotes because Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara) doesn’t actually kill anybody; he rather carries murder like an infection, triggering violence in a series of ordinary people as he wanders through the story. Before we meet him, we follow Detective Takabe (Kôji Yakusho) as he investigates a series of brutal murders in which each victim is mutilated in the same way, each killer remaining near the victim, calm yet puzzled by their own actions, becoming angry and confrontational when pressed to explain those actions. When Mamiya is finally introduced, he is an amnesiac who keeps asking where he is; with no memory of himself, he keeps asking others who they are, an unsettling question which seems to unmoor them, opening some inner door through which the violence emerges. The release of this potential for violence is terrifying to those who commit the murders. (What we do eventually learn is that Mamiya was a medical student who developed an obsessive interest in Franz Mesmer, the 18th Century German physician who first posited the idea of “animal magnetism” which became the basis of hypnotism.)

Takabe is susceptible to the influence Mamiya exerts because he himself is uncertain of his own identity. At work, he’s the diligent investigator determined to solve a mystery and end this violence; but at home he is the helpless husband of a woman who is slipping away into madness. He tries to communicate with her, to reassure her that they can resume a normal life, but she keeps drifting further away. After meeting Mamiya, he has a chilling vision of her hanging in their kitchen, her death a sign of his failure, but also an unadmitted fulfillment of his own desire to be free of her.

Meanwhile, even in custody Mamiya continues to spread his infection, causing more ritual murders. Towards the end, everything gets increasingly murky – both literally, as the image gets darker and grainier, and figuratively, as characters drift into visions and dreams which seem to promise some new information only to stubbornly withhold anything conclusive. The psychiatrist Sakuma (Tsuyoshi Ujiki) shows Takabe a brief movie clip of what purports to be a hypnosis session in a hospital in 1898; the female subject, we’re told, later murdered her son in the same way as the current victims, suggesting that the “infection” preceded Mamiya.

In what constitutes a climax of sorts, Takabe visits a derelict wooden building, perhaps the old mental hospital where that film clip was shot. Here he has a final meeting with Mamiya, who has escaped custody. But again, we learn nothing … Mamiya makes a cryptic remark about this place being where people come for self-knowledge; the suggestion is that Takabe has learned something vitally important … but we don’t know what it is. And then he finds an old cylinder phonograph, holding out the hope that we will finally hear some crucial piece of information – but the scratchy, skipping voice gives us only word fragments which convey nothing. And yet, Takabe has been transformed. In the final scene, the detective seems relaxed and confident, finishing a meal in a restaurant. He has found equilibrium, but may himself now be the carrier of the infection – in the background we get a quick glimpse of his waitress picking up a large knife and moving with determination just before the shot abruptly ends …

The desire for revelation and resolution is a powerful one, so the willful withholding of such narrative information is a radical act on the part of the filmmaker, establishing a deliberate conflict with his audience. Watching Cure again (for the third time; I also saw it on DVD some fifteen years ago), I felt myself resisting that conflict, holding back from full commitment to the movie … and yet now, after writing about it, I find that I’m being drawn back to it; but whether this is in hope that somehow I’ll be able to penetrate its enigma and finally understand just what the heck it’s saying, I’m not sure. Its very refusal to provide narrative closure means that I can never quite be free of it … like Mamiya’s victims, I’ve been infected by Kurosawa’s mysterious influence.

Comments

Not much of a Kiyoshi Kurosawa fan here. I know I’ve seen Pulse and bug House and I think I’ve seen Cure. The later isn’t on my watched movie list so who knows. I didn’t care for any of them much. Just not interesting to me. I like a story.

True, he does put atmosphere and mood above any traditional notions of story. So it’s really a matter of personal taste.

Great article, thanks. The technical elements of the film are astounding. It wasn’t until the shot of Sakuma, just after he shows Takabe the grainy tape, that I realised just how spooked I was. Part of the reason we are so drawn in is because Kurosawa doesn’t offer any logical motive or comprehensible explanation of the events and, what makes the film feel so exceptional, is that Kurosawa manages to convey this through the technical aspects of the film itself. Western cinema – especially American cinema – still has such a singular obsession with narrative and exposition, and Kurosawa demonstrates with this film how limiting that can be.

Exactly. This is what I like about Japanese (and Asian) horror in general … and why U.S. remakes of movies like The Ring are almost always disappointing: they take out the deeper mystery by adding in backstory and explanations. Films like Cure and Kurosawa’s Kairo (Pulse), and Shimizu’s original Ju-on (Grudge) create entirely convincing worlds where disturbing events can never be explained away, which is why they leave you with such a deeply unsettling aftertaste.

“Its very refusal to provide narrative closure means that I can never quite be free of it … like Mamiya’s victims, I’ve been infected by Kurosawa’s mysterious influence.”

A brilliant insight, Mr. Godwin. I just watched CURE for the first time over the weekend, and it’s still lingering with me. This is easily the best piece of writing I’ve found on the picture so far. There’s an almost Lynchian quality to the hallucinatory dream imagery that permeates the last act of the picture. I think the elliptical, allusive style harkens back to many of the great American films of the 70s, even if it’s a completely different beast altogether. The final shot bowled me right over, as it is meant to. It is audacious to frustrate expectations to this extent but that is precisely what I admired about it. For me, if there is a weakness in the picture it lies in the fact that the character of Mamiya is annoying – an obnoxious presence, rather than a disquieting one. It is Takabe who is far more haunting, a deliberate choice I’m sure, but I’m still left wishing Mamiya had been directed differently.