Dr. Seuss’ Nightmare: The 5000 Fingers of Dr. T (1953)

There are some disks whose special features, although they provide a lot of interesting information about the movie and its production, nonetheless irritate me. This happened recently when I watched and listened to everything included on Indicator’s Blu-ray of The 5000 Fingers of Dr. T – which I hasten to add presents the film itself in a beautifully restored, eye-poppingly colourful transfer. This singularly original movie has a troubled production and release history, but is prodigiously imaginative, musically inventive, constantly surprising in its tonal shifts … yet almost everyone who contributes to the disk seems to go out of his or her way to remind us that, despite all this, it’s not actually a “good movie”, but rather a strangely deranged crippled thing which ended up satisfying no one, including its makers. (Even the astute DVD Savant Glenn Erickson savages the film almost mercilessly; but it should also be noted that Jello Biafra of The Dead Kennedys once said that it’s his favourite movie.)

While all of this may be true, the actual experience of watching Dr. T makes it irrelevant and the cumulative effect of the nit-picking is to give the impression that somehow we viewers should temper our enthusiasm for what the movie actually does achieve. (This reminds me of the absurd comment I read years ago in some guide to movies on TV – I think it might have been Leonard Maltin – insisting that viewers must remember while watching Casablanca that it’s just a very dull World War Two espionage tale, as if what really matters in this supremely romantic movie is the bare bones of the plot rather than the characters and their relationships and conflicts.)

The 5000 Fingers of Dr. T (1953) is unlike anything else, a strange, mad thing which provokes a sense of wonder that it exists at all. Emerging from a collaboration between Theodor Geisel and Stanley Kramer, who had met in the Signal Corps during the war, it’s a musical fantasy steeped in so many childhood anxieties that it was more likely to trigger nightmares in kids than amuse them. Written by Geisel before he fully became the famous household name Dr. Seuss, and originally intended for Kramer to direct, the movie was designed (by Rudolph Sternad) to replicate Dr. Seuss’ eccentric visual world in three dimensions and live action, with music by Frederick Hollander which contains distinct echoes of the Weimar cabaret style of Kurt Weill. (Not surprising since Hollander – then Friedrich – spent much of the ’20s writing music and lyrics for a Berlin cabaret; he also wrote the songs sung by Marlene Dietrich as Lola Lola in Josef von Sternberg’s The Blue Angel [1930].) In the event, Kramer produced but didn’t direct; that chore went to Roy Rowland, a man with the kind of eclectic filmography which marks a studio hand rather than an auteur – and there’s nothing else in his work to match Dr. T.

But not only was the film conceptually unusual; it was made for a studio (Columbia) not noted for musicals, and certainly not for something this far from the mainstream. Previews were disastrous; Kramer went back into the editing room (without Rowland) and drastically re-cut and reduced the film – legend has it that no less than ten musical numbers and more than a half hour of running time were cut out. It was restructured and some things were re-shot. The end result was an 89-minute plunge into Oedipal anxiety and fears of totalitarian oppression and nuclear destruction.

Young Bart Collins (Tommy Rettig) is trapped inside the family home by demands that he spend his time practising the hated piano; his mother Heloise (Mary Healy) has engaged the overbearing Dr. Terwilliker (Hans Conried) as his teacher, a despot who disdains all other instruments and insists that Bart must devote every waking moment to his practise. Bart looks to plumber August Zabladowski (Peter Lind Hayes) for support, but the working man is too preoccupied with his own business. Exhausted, Bart falls asleep at the piano and finds himself in the nightmarish alternate world of Dr. T’s Happy Fingers Institute, where he’s destined to be imprisoned with 499 other boys, all of them condemned to eternal practice on one vast piano.

Heloise is under the crazed teacher’s hypnotic influence, managing the Institute for him, and scheduled to marry the doctor who will thus become Bart’s stepfather. Mr. Zabladowski is so busy installing all the sinks required to get the institute up to code for the grand opening tomorrow that he doesn’t have time to listen to Bart’s warnings about Dr. T’s sinister plans. And below the Institute’s labyrinthine halls, there are dungeons in which musicians who play all other forbidden instruments are imprisoned.

It’s up to Bart to find a way to foil the musical dictator, first providing an economic incentive for Mr. Zabladowski to help him, then finding more personal reasons – specifically by suggesting that the plumber could marry Heloise himself and become Bart’s father. Ultimately, Bart and Mr. Zabladowski must collaborate to save themselves from the dungeons and invent a device to block Dr. T’s plans – a device which distorts music into meaningless garbled noise and is so unstable that it may blow the whole place up.

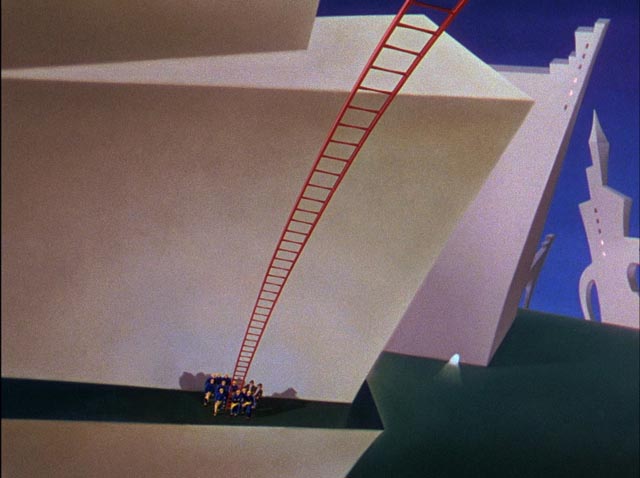

Along the way, there are endlessly inventive details (the menacing twins on roller skates who are conjoined by their lengthy shared beard; the army of working-stiff guards; the radically distorted perspectives of the sets; the tortured musical souls in the dungeons) and demented musical numbers. Highlights include a protracted hypnotic duel between Dr. T and Mr. Zabladowski in the form of a tango; an elaborately choreographed ballet involving the prisoners in the dungeon who play an array of Seussian musical instruments; and a deeply disturbing descent in an elevator run by a masked figure reminiscent of an executioner who announces each floor and the torments to be found there. The pinnacle, though, is the lively and perverse “Dress Me” number in which Dr. Seuss’ wordplay is given full-rein (“undulating undies”) as Dr. T is dressed in his mad dictator’s uniform in preparation for the Institute’s grand opening.

All of this pushes Bart’s performance anxiety to heights (or depths) far beyond reason; it also suggests a postwar distrust of artists and intellectuals combined with a subversively leftist respect for immigrants and the working class. These political undertones are somewhat murky and contradictory (it was made at the height of the post-war Red scare) – and perhaps they were more coherent in the original full-length version – but the film is held together by the strange intensity of its dream logic, the deep fear Bart has that his mother has fallen under the influence of a sinister and dangerous would-be father rather than the bluff and likeable alternative. Perhaps the most problematic yet typical-of-its-time aspect of the film is the conflation of fascism and artist/intellectual in the character of Dr. T; this creates a false linkage between the very real political dangers recently faced in the war and a deep-rooted American anti-intellectualism with its distrust of effete (and sexually ambiguous) academics. But on a creative level, the film contains more than this, and despite such objectionable thematic points its focus on Bart and his determination to resist authoritarian control provides a positive counterpoint to such retrograde ideas. (This regressive element seems surprising given the unquestionably liberal attitudes of Kramer and Geisel, and may simply be an inadvertent “side effect” of the choice of narrative elements: the story grows out of Bart’s resentment at being forced to practice an instrument he’s not really interested in … which leads to his piano teacher being the villain … rather than the teacher being first chosen as a villain and then having the narrative constructed to accommodate him.)

The cast is more than up to the task of making this work to a satisfying degree, with Peter Lind Hayes and Mary Healy (married in real life) providing something like an anchor for the weirdness by playing a familiar sit-com couple who don’t realize for a long time that they’re really suited to one another. Tommy Rettig is excellent as the kid who, while misunderstood and abused by adults, is determined to find his own solution to the problems he faces. But the movie is undeniably dominated by the manic, aggressively effete performance of Hans Conried as Dr. Terwilliker, a masterpiece of character comedy. The chorus of dancers in the dungeon, green and emaciated as if being devoured by mold, is like a musical comedy evocation of one of Dante’s circles of Hell; and it’s a mystery where the filmmakers found all those minions, a pug-ugly bunch of dockworkers and teamsters who nonetheless join in amusing harmony on an old school song.

The 5000 Fingers of Dr. T is about a child’s sense of powerlessness and his ultimate ability to overcome the oppression of adults and reshape the world more to his liking. Regardless of its flaws and its failure to be a “well-made” film, it’s a terrific piece of entertainment which insists on engaging the audience on its own terms.

*

Indicator’s disk is packed with those extras I mentioned above, beginning with a ragged commentary by critics/historians Glenn Kenny and Nick Pinkerton (who don’t quite sound prepared for the task – there’s a fair amount of fumbling and audible shuffling of paper as they try to make their points); featurettes include a very brief introduction (2:11) from Karen Kramer, the producer’s wife; Crazy Music (16:25), an interesting interview with music archivist Michael Feinstein who recounts his efforts to track down the missing pieces of the film’s score; Father Figure (18:32), an interview with Roy Rowland’s son about his father’s career; Dr. T on Screen (14:34), comments from a variety of people about the film, including Cathy Lind Hayes, daughter of Mary Healy and Peter Lind Hayes, and dancer George Chakiris, who appears in the dungeon ballet; and A Little Nightmare Music (11:45) about the innovative score. Despite my misgivings about all the nit-picking, overall it’s an excellent package and it’s nice to see someone put this much effort into such an odd – and commercially unsuccessful – movie.

*

ADDENDUM

It was from the disk extras that I learned that Michael Feinstein had spearheaded a decades-long effort to track down all the pieces of the original score, a daunting task which eventually led to a comprehensive three-disk CD release in 2010. Naturally, I immediately went on-line to look for the CD. Things didn’t look too promising at first, with prices ranging from around $60 to $140, although I wasn’t too surprised as the release had been a limited edition of only 3000 copies. But then I had the bright idea of checking the source – it had been issued by Film Score Monthly – and it turned out it was still available from Screen Archives Entertainment at the original price of $34.95. So needless to say I ordered a copy.

Comprehensive hardly describes the package. The first disk-and-a-quarter is a reconstruction of the original version of the movie with almost all of the lost songs and cues restored in their correct order. These were culled from archival acetate transcription disks, which occasionally have compromised quality, but are mostly quite serviceable. Not surprisingly, this version sounds more fully developed than the finished film, with more songs to flesh out the characters and their relationships. The rest of the set comprises alternate versions of some tracks, additional unused material, musical sketches and the tracks as they are heard in the finished film.

Listening to this reconstruction is a tantalizing experience, providing an (aural) glimpse of a lost film which would have been quite different from what we can see in the movie as it exists. Yet another addition to that always expanding wishlist for the rediscovery of fragments of cinema history which were discarded through carelessness driven by commercial imperatives.

Comments

I’ve always liked that movie a whole lot. I’ve seen it several times over the years and plan to watch it again. I bought the cheap Mill Creek Blu-ray and that should suffice, I doubt I’ll bother with this Blu-ray. I am tempted by the CD. I might order that.

I’ve always found reviews like the Maltin you mentions about Casablanca really annoying and one of the reasons I quit reading a lot of review books and sites.

I watched the first of the Jean Gabin Maigret films today, for some reason the library only had the second available and after watching that I ordered both from Kino Lorber. They had a sale on them and they arrived today. The first was as entertaining as the second. I’m glad to have picked them up.

I haven’t seen the two Maigret movies, but they look interesting … in fact, I’m pretty sure I’ve ever seen anything by Jean Delannoy, but I think he’s one of the directors Bertrand Tavernier talks about in his documentary My Journey Through French Cinema.