Haunted by the past: Karl Marx City (2016)

I was browsing in a local bookstore last week when my eye was caught by the cover of a particular DVD. The striking black-and-white design suggested something noirish and menacing, while the title seemed to allude to the exaggerated genre stylings of Sin City. However, Karl Marx City (2017) turns out to be a highly personal documentary which delves into the intersection of history with familial tragedy.

Co-director Petra Epperlein grew up in East Germany in the almost comically named Karl Marx City (previously, and since the fall of Communism, Chemnitz). After the reunification of Germany, she moved to the United States. In 1999 she was called home because her father had committed suicide. There were anonymous letters suggesting that he had been an informer for the dreaded Stasi, the political police of the German Democratic Republic. Though this suggestion hung over the family, it wasn’t until more than ten years later that Epperlein returned to Germany to begin a documentary investigation into her own father’s life.

But the film expands from there to an examination of the surveillance state and how it shaped everyday experience for a population of millions. Epperlein and co-director Michael Tucker interviewed former Stasi operatives, victims, academics and the guardians of the vast Stasi archive which holds files on millions of citizens. They also had access to surveillance photographs, movies and videos which provide glimpses of people going about their daily business, material which by its very existence provokes questions about what in other circumstances would be perfectly normal behaviour. When everyone is being watched all the time, everything seems suspiciously meaningful.

While constantly circling her own family story – Epperlein’s mother and brothers are interviewed – the film creates an Orwellian picture of the paranoia, fear, and suspicion which permeated every aspect of life in the GDR with the deliberate intent of isolating every citizen in order to ensure obedience and loyalty to the state. One of the chilling points being made is that those in charge believed deeply and seriously in their mission; this wasn’t some form of cynical self-interest but rather a determined attempt to construct a “perfect society”. The result of that attempt was the replacement of individual perception and understanding with an official “truth” which largely neutered any attempts at resistance.

While the personal story becomes tense and emotional, the political story is illuminating (even more so now perhaps as we are witnessing in real time the construction of another official “truth” in the United States, where currently reality is losing traction in service of a deeply corrupt ruling clique); the sections dealing with the Stasi archives evoke an almost overwhelming sense of futility, the sheer amount of material collected by this system seeming to ensure its own ultimate collapse. The most blackly comic moment comes when we see staff patiently piecing together documents hastily shredded when the end came – thousands of large black garbage bags full of torn files. Why didn’t those involved burn all this material? The attempted destruction seems only half-hearted … and yet, who could have believed people would spend years of their lives taping the pieces back together again? It’s all so absurd.

When Epperlein and her family finally acquire documents relating to her father from the archive, the emotional fall-out is complex – for her, for her mother and her brothers. What she learns is just one small part of a much larger understanding of how this oppressive state functioned and just what it did to its citizens psychologically and emotionally.

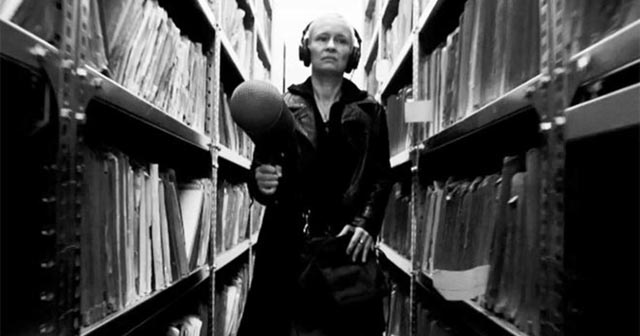

Karl Marx City is a richly layered enquiry into one of the most important political stories of the Twentieth Century, given depth by the filmmaker’s personal connection to that story. It is shot in high contrast black-and-white which both draws on memories of film noir and comments ironically on a fascist aesthetic which asserts a stark moral clarity while aggressively concealing all ambiguity. Only towards the end, as some kind of personal resolution is being found, does the film switch to colour … providing a visceral sense of emerging from a nightmare into normality.

Comments