Indicator Blu-rays, part two: America in the 1970s

The final two of five Indicator disks I recently purchased are up to the same excellent level of quality as those I’ve recently written about. Flawless transfers and extensive informative supplements make them essential buys.

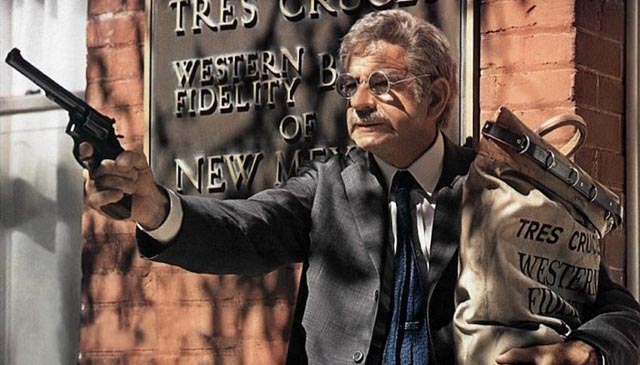

Charley Varrick (Don Siegel, 1973)

After making four Clint Eastwood-starring movies in a row, from Coogan’s Bluff (1968) to Dirty Harry (1971), director Don Siegel had not simply gained enough commercial clout to do what he wanted, he had honed his craft to the point where he could, seemingly effortlessly, make the finest film of his career. It’s ironic then that the studio with which he had had a long and profitable relationship basically dumped the film, guaranteeing box office disappointment despite a generally good critical reception.

Why Universal had no faith in Charley Varrick (1973) is a mystery, although perhaps they had expected something different in the wake of Dirty Harry. The latter had been a huge hit, establishing Eastwood as a mythic figure on screen and off. Walter Matthau as the titular Charley was another thing entirely, a rumpled figure mostly known for his comic screen persona (though he had actually already played a number of bad guys in movies and on television). Ironically, it had been the studio which wanted Matthau for the role, feeling that Siegel’s original choice, Donald Sutherland, was less commercial.

Based on a novel called The Looters by John Reese, with a script by Howard Rodman (who had previously worked with Siegel on Madigan [1968] and Coogan’s Bluff) and Dean Riesner (Coogan’s Bluff and Dirty Harry, as well as Play Misty For Me [1971] and High Plains Drifter [1973] for Eastwood), Charley Varrick is the story of a small-time bank robbery that escalates into something much more complicated – both superficially leisurely and deceptively simple, it’s intricately plotted and directed with consummate skill by Siegel.

Charley, “the last of the independents” as he bills himself, is a crop-duster pilot who supplements his income with the occasional robbery, aided by his wife Nadine (Jacqueline Scott) and sidekick Harman Williams (Andrew Robinson, the Zodiac killer in Dirty Harry). The Tres Cruces bank is small and the gang expect to walk away with a few thousand. But things quickly go wrong – a bank guard and a couple of cops who happen by are shot, the small town is somewhat wrecked by crashing cars during the escape, and Nadine is fatally wounded. That’s a lot of havoc given the expected small take, but when Charley and Harman finally make it to safety in their trailer park base, they discover that a couple of sealed bags taken during the robbery contain three-quarters of a million dollars.

Harman, a bit dumb and far less experienced than Charley, thinks they’ve hit the jackpot and immediately plans to take his cut and live high. But Charley, particularly after the news reports mention only a few thousand, realizes that this is mob money; that the bank was a drop, a temporary holding place before the money is moved on for laundering. Which means not only are the police after them – for robbery as well as for killing cops and the guard – but the mob is too, and they’ll be even more relentless.

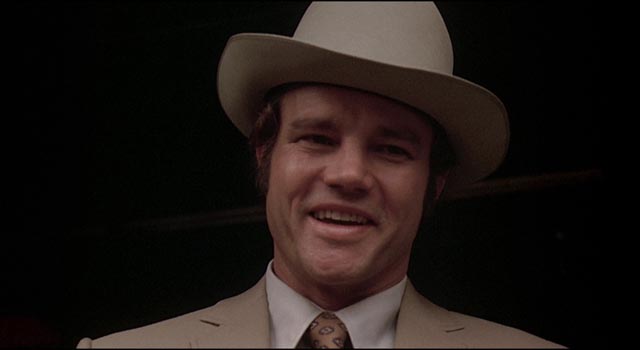

The ripples quickly spread. Those at the top of the mob can’t believe the heist was just a coincidence, which means that someone on the inside must have tipped off the gang about the money, which was scheduled to be in the bank for just a couple of days. A laid back yet vicious hit man is put on their trail. The ironically named Molly is played by larger-than-life Joe Don Baker in his first movie after playing Buford Pusser in Walking Tall (also 1973). He’s soft-spoken, always seems to have a slight smile, smoking a pipe and wearing a big cowboy hat … and has no hesitation about inflicting pain on anyone who seems to be withholding information he wants to know.

Meanwhile, mid-level mob guy and respectable businessman Maynard Boyle (John Vernon, the mayor of San Francisco in Dirty Harry) realizes that he and the bank’s timid manager Harold Young (Woodrow Parfrey) are inevitably going to be suspected of betraying their bosses, that their lives are now essentially forfeit.

As these forces gradually close in on Charley and Harman, Charley quietly sets about devising his own escape. Matthau is superb in the role, laconic and subtly expressive. The look in his eyes at the moment Harman tells him that he won’t wait years to spend the money is chilling; without a word, he shows us that Charley will sacrifice his younger partner to pave the way out of this fix. Siegel gives us every detail of the plan without emphasis, allowing the audience to piece things together, sometimes expecting us to wait patiently for a point to become clear – and in the end they all do. As co-writer Rodman’s son, Howard A. Rodman, says in the extras: a great script supplies one surprise after another while you’re watching, but then looking back in retrospect everything seems inevitable. Charley Varrick is exemplary in this respect; it all fits together like a precision machine, yet while you’re watching it’s fraught with uncertainty and suspense.

The fulfillment of Charley’s plan is satisfying emotionally and intellectually … and yet once out of the film’s grip, it becomes clear just how problematic the narrative is. Matthau’s casting turns out to be crucial here; he’s calm, laid back, combines chilly calculation with easygoing humour – and is ultimately responsible for a large number of deaths, starting with those killings during the robbery, including his own beloved wife (the moment of her death is played so quietly, yet with such deep emotion, that Siegel’s subtlety as a director is seen in sharp relief). Low-level mob guys are doomed by the coincidence of the robbery; Molly brutalizes a number of people as he relentlessly pursues the robbers, these also Charley’s victims at one remove.

Dirty Harry was condemned by many critics at the time for its cynicism and its seeming advocacy of violence committed by a representative of the law, but Charley Varrick was embraced by some of those same critics when the force of disorder was an outsider, and an amiable one at that, who exhibits none of Harry’s chilly sadism. Charley is smart and likeable and he formulates and carries out an admirably effective plan for his own survival – at the expense of everyone he comes into contact with.

By the mid-’70s cynicism had taken firm hold in Hollywood with the easing of censorship and the disintegration of social and political norms in the wake of Vietnam and Watergate, but movies like Three Days of the Condor, The Parallax View, Night Moves, Executive Action were all inflected by a kind of hopelessness, a feeling that there could be no escape from this societal collapse. By centring Charley Varrick on small-time criminals and making Charley such a calm, intelligent character, Rodman, Riesner and Siegel propose that a smart “independent” can navigate this chaos and get away with the rewards of his crime. In retrospect, the opening title montage with its lyrical, bucolic imagery of a small town coming to life at dawn – a flag being raised outside the post office, kids playing in a sprinkler, a girl mowing a lawn, a small boy struggling to put a saddle on a mule – suggests an idealized view of America, a self-image which is clung to despite the horrors which threaten to overwhelm it. The final image of Charley driving away from a junkyard with its burning debris and dead bodies is the America which has replaced that mythic land of peace and harmony. Ruthless selfishness, not communal life, is the key to survival here.

And perhaps, whether this was fully realized at the time or not, this is why Universal shied away from the film. On its surface Charley Varrick is a small, well-crafted B-movie about a bank robbery; but under that often leisurely surface, it’s a subversive dissection of the state of the nation at a particularly turbulent moment. A perfect expression of neo-noir, from its impeccably constructed script to its flawless cast to Don Siegel’s effortlessly assured direction, his control of pace and tone, without a wasted moment (well, maybe with the brief exception of Charley’s quick tryst with Maynard Boyle’s secretary [Felicia Farr]), Charley Varrick is exemplary of the virtues of the kind of filmmaking nurtured for decades by the studio system, here put in service of undermining the kind of assurance about the world which that system promulgated.

Mastered from an HD transfer supplied by Universal, it looks beautiful on the disk, a colourful, detailed image which retains the visual texture of the forty-five year old film. The extensive extras include another fine documentary from Robert Fischer, Last of the Independents: Don Siegel and the Making of “Charley Varrick” (2015, 1:15:19), which covers the production in detail through interviews with actors Andy Robinson and Jacqueline Scott, stunt driver Craig R. Baxley, Howard Rodman’s son, Howard A. Rodman and Siegel’s son, Kristoffer Tabori. There are two substantial archival audio supplements, both recorded at the BFI’s National Film Theatre – one with Siegel from 1973 (1:14:00), the other with Matthau from 1988 (1:28:43). There’s a super-8 home movie cut-down version (17:34) and Howard A. Rodman and Josh Olson provide a Trailers from Hell commentary for the original trailer. The 40-page booklet contains an essay by critic Richard Combs, excerpts about the production from Siegel’s autobiography, and a selection of contemporary reviews.

*

Little Murders (Alan Arkin, 1971)

Of the five Indicator disks I bought recently, the one I was most eager to watch, but also most nervous about watching, was Little Murders. Knowing what I do now about the film’s commercial failure and limited distribution, it seems remarkable that I could have seen it at all on its brief release in 1971. I was in my mid-teens back then and living in Newfoundland, with only three theatres in St. John’s. In my memory, I seem to recall going to see it more than once, but that’s probably unlikely. I wasn’t keeping any records back then, and I lived a half-hour bus ride outside the city. All I recall for sure is that the movie made a very strong impression and I’d never had an opportunity to see it again in the subsequent forty-seven years. The potential for disappointment after all that time was high … I’ve changed a lot, movies have changed a lot, and quite a few films from that era are so trapped in their time that they exist now only as curiosities.

The first and most striking thing about watching it again on Blu-ray is that although I had a memory of the vague outlines and, more particularly the very blackly comic tone, I had very few memories of specific details. In fact, the film continually surprised me because I had no idea what was coming next at any moment. But that memory of tone was accurate. An intense impression of madness and anger permeates it. And while the fashions and haircuts are quaintly dated, the ferocious humour seems completely undated.

Little Murders was the first film script written by Jules Feiffer, based on his own play. It was the first feature directed by actor Alan Arkin, who had previously directed the play off-Broadway. It was the first feature produced by star Elliott Gould (with his partner Jack Brodsky), exploiting his power as a major star at the time. And it was made at a time when corporate power was loosening its hold on production, taking chances in hopes of capturing the interest of a fragmented, politically engaged younger audience. Feiffer, Arkin and Gould were left to their own devices to make the film they wanted to make. In this, they were greatly aided by cinematographer Gordon Willis, a craftsman noted for his risk-taking with unconventional lighting, and camera operator Michael Chapman, who flawlessly follows the action in scenes often covered in long continuous takes.

While the film is structured around these extended scenes, often with lengthy monologues, the camerawork keeps it from feeling like a filmed play; the audience is immersed in the scenes by a camera which dances with the actors.

Feiffer had been working on the project for years, initially attempting to write a novel to deal with his visceral response to the assassination of JFK and subsequent public murder of Oswald. By the time he had transformed that failed novel into a play script, there had been much more violence, with war protests and assassinations; events helped him to hone his critique of the violence which had come to seem an integral part of American life (a critique which depressingly seems just as pertinent and pointed today as it did almost five decades ago).

*Spoilers ahead*

There are two responses to this violence embedded in the script, complimentary but at odds. These are embodied in Alfred Chamberlain (Gould, in arguably the best performance of his career), a photographer (an observer, standing outside), and Patsy Newquist (Marcia Rodd), an interior designer. They “meet cute” as the film begins, with Alfred being beaten by a gang of young thugs just outside her apartment window. When she runs down and tries to pull them off him, they turn their attention to her and he just walks away. She runs after him, furious that he did nothing to help her; he responds that it was her own fault because they were getting tired of beating him when she showed up and reinvigorated their anger.

Alfred is a self-professed Apathist; he observes, but does and feels nothing. He was a successful fashion photographer but lost his taste for the business; unable to photograph anything but distorted, off-putting expressions on the models, he turned to shooting objects, becoming a successful and influential catalogue photographer. When people began to see these images as some form of artistic expression, he became disgusted all over again and now spends his time taking nothing but pictures of dog shit on the street. But these images too are now being praised and given awards – the culture has become so morally bankrupt that it embraces any and everything, no matter how offensive and vacuous.

Patsy, on the other hand, feels everything and embraces life. No matter how bad things get she finds the bright spot and carries on. One aspect of this is a string of relationships in which she sets out to reform and reshape men into more positive selves. Alfred seems to be what she’s been working towards, an intractable project. Between her forcefulness and his apathy, they become a couple. The more he fails to respond to her efforts, the more determined she becomes.

The film’s first big set piece is Alfred’s introductory visit to Patsy’s family. He’s reluctant – he doesn’t like families (in fact hasn’t seen his own parents since he left home at seventeen) – and in the event, his reluctance turns out to be warranted. The Newquists are a manic sit-come family, with a gruff father (Vincent Gardenia), who rails against societal decay (particularly what he sees as gays everywhere); a fifties Mom (Elizabeth Wilson), whose world revolves around doting on her husband and children and getting to the table to share meals; and son Kenny (Jon Korkes), seemingly trapped in a nightmarish perpetual adolescence, swinging wildly between childish antics and sullen hostility. Everything about the family is ramped up and exaggerated, diametrically opposed to Alfred’s apathy. While he is withdrawn from the world, they hold it at bay with a kind of shared madness predicated on the idea of familial bonds.

Despite his bemused dislike of the family’s energy, Alfred agrees to marry Patsy, and the wedding is the second big set piece, courtesy of Gould’s M*A*S*H co-star Donald Sutherland. Sutherland’s speech as the Reverend Dupas is a bitingly funny dissection of non-committal belief – everything is fine, everyone is fine, even failure is success, so it doesn’t matter that virtually all the marriages he has presided over have failed. He accepts a cheque from Mr. Newquist to slip a mention of God into the ceremony against Alfred’s wishes, but in deference to Alfred doesn’t mention the deity; but he does tell everyone about the bribe. And when he betrays Kenny’s trust by mentioning that “it’s okay to be gay” (something Kenny confessed to him before the ceremony), the wedding devolves into a brawl.

All this puts stress on Alfred and Patsy’s relationship; he goes to their apartment and she goes home with her parents. When she joins him in search of reconciliation, Alfred goes into a monologue which in many ways is the core of the film, a superb piece of writing and a gripping piece of performance. He tells a story from his college days, when he was involved a little in protests and the FBI put him under surveillance. Every day his mail arrived later because someone was opening and reading it, so he began writing letters to himself – or rather to the agent reading his mail – trying to make contact, to awaken the unknown agent to just how pathetic and pointless his job was; he invited him up for coffee and a chat … but the man never appeared and Alfred’s last letter never made it through the screening. In some way, he had destroyed this low level agent of the state whose life was devoted to spying on people who weren’t worth spying on.

Telling this story is cathartic for Alfred; at his most vulnerable, he is finally ready to succumb to Patsy’s insistent demands that he open himself to feeling, that in effect he start living again. And at this moment of maximum vulnerability, Patsy is shot to death in his arms by a sniper firing through the window, plunging him into a virtually catatonic stupor. Covered in blood, Alfred rides the subway – watched with sidelong glances by fellow passengers who want nothing to do with whatever trouble he’s in. Taken in by the Newquists, he’s tended like a newborn, spoon-fed and reassured.

Alan Arkin the actor finally appears as police lieutenant Practice, a frightened, paranoid, jittery man overwhelmed by the hopelessness of his job – trying to stem an endless tide of violence. There are hundreds of unsolved murders in the city and the only thing they have in common is that they have nothing in common… This is the last of the rants we hear from male authority figures – Mr. Newquist, who sees society failing because of the rise in openly expressed homosexuality; Judge Stern (Lou Jacobi), who rails against a disrespect for the law, and more particularly, a disrespect for religion, which is causing social breakdown; Reverend Dupas, who is complicit in the deconstruction of patriarchal religious authority and the rise of laissez-faire morality. There are no certainties left to sustain people, all replaced by fear and distrust, anger and hatred, all leading to violence as, apparently, the only way to assert oneself.

Alfred retreats to a city park, sitting on a bench in sunlight, people moving around him, going about their lives. He finally picks up his camera and begins looking at the world again through the lens – at first trees, the sky, then gradually faces, old, young, sad, happy … he’s slowly coming back to life…

And, reinvigorated, he returns to the Newquists, now carrying a bouquet of flowers for Mrs. Newquist in one hand, a high-powered rifle with telescopic sight in the other. He and Kenny fumble with it, neither really knowing how it works; then Mr. Newquist takes it and loads it and the three of them take turns shooting down into the street, no longer resisting or hiding from the violence around them, but freely participating in it, rejoining a society in which such violence has become the norm. Mrs. Newquist wheels a serving cart in from the kitchen – “Come and get it!” – and they join her at the table, appetites refreshed, and the camera slowly moves in on her smiling face, so pleased to be surrounded again by a happy family…

Perhaps it’s not surprising that Little Murders wasn’t a commercial success, despite some really enthusiastic reviews from major critics. It’s a funny film, Feiffer’s dialogue is rich and resonant, and the performances are terrific, but the comedy never conceals the darkness and anger. Rooted in the violence and social disorder of the ’60s, it now seems chillingly prescient of the toxic idea which has taken hold of large sections of the U.S. population: that every American should be heavily armed because every other American is a potential threat. Perhaps the closest thing to this film that I can think of is Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (1985), a dark yet funny nightmare vision of a broken society and ordinary people struggling to find ways to survive forces they have no power to control and barely understand.

While I was initially nervous about watching Little Murders again after so long, it more than lives up to my vague yet positive memories, and Indicator’s Blu-ray will stand high on the list of this year’s best releases.

For a film which all but disappeared after its brief, unsuccessful theatrical release, it has been treated with impressive care by Indicator. The HD transfer provided by 20th Century Fox has a wonderful film-like quality, with appropriate grain and a lot of detail even in darker scenes. While there is visible noise in some of the darker scenes, this looks more like a quality of the original film stock than a flaw in the transfer.

The disk is packed with almost two-and-a-half hours of extras, plus two separate commentary tracks – one with Gould and Feiffer, the other with film journalist Samm Deighan.

For the rest, there are new interviews with Gould (17:34), Feiffer (31:31) and Arkin (18:23), all of which are engaging and informative about the history of the production and their intentions when making the film.

There are a couple of interesting archival audio extras, apparently distributed at the time on 12” vinyl for promotional purposes. Interviews with Gould, Sutherland and Arkin (31:37) are accompanied by scripts intended to help local radio hosts to insert themselves, to make it sound as if your local morning guy was actually interviewing these celebrities. More interesting, though, is a complete episode of Speaking of Films (30:11) in which Feiffer discusses his play and the film with a panel which includes Susan Rice, Robert Geller, Sean Driscoll and Leonard Maltin. It’s an intelligent conversation which reminds us that movies were once treated as significant cultural entities rather than mere entertainment and commercial properties.

Finally there’s a trailer (3:32), a Trailers from Hell commentary by Larry Karaszewski (3:48), several TV (1:51) and radio (2:34) spots, and an image gallery of 50 production stills and advertising elements.

The 40-page booklet contains an essay by musician and filmmaker Jim O’Rourke, excerpts from various sources about the production and personnel, Fox promotional copy and a study guide “for school, college, press, church and family discussion groups” (how times have changed!), and excerpts from contemporary reviews.

Comments