Recent viewing, Summer 2018

Two from Vinegar Syndrome

Although I’ve been aware of Vinegar Syndrome for some time, having seen some of their releases in a local store and promoted on-line by sites like Diabolik DVD, I haven’t been much tempted to sample their catalogue. Their releases seem to tend towards the low end of the budget and aesthetic scales – cheap exploitation movies, leaning towards porn. I did pick up their Blu-ray of Simon Wincer’s Snapshot (1979), a minor addition to the Ozploitation wave of the 1970s and ’80s which I’d seen in its original theatrical release; it was co-written by one-man Aussie genre factory Everett De Roche (Patrick, Long Weekend, Harlequin, Road Games, Razorback and many others), so it was kind of a sentimental purchase. The disk itself is quite impressive, with both the U.S. and original Australian cuts of the feature, a commentary by director, producer, cinematographer and star, an interview with producer Tony Ginnane, and extended interview clips from Mark Hartley’s Ozploitation documentary Not Quite Hollywood (2008).

So having broken the ice with that disk, I recently took a chance while browsing in that same store and picked up two more VS releases (the company’s name, by the way, refers to the process of decay which old nitrate prints go through, a kind of chemical rot which produces often quite beautiful visual transformations of the image). I’d never heard of either of these two movies before; both are low budget independent horror/thrillers from the cusp of the 1990s, both rooted in the psycho-serial-killer subgenre … and both are sufficiently original and inventive to overcome production limitations.

*

Blue Vengeance (J. Christian Ingvordsen, 1989)

Blue Vengeance (1989), co-written and directed by J. Christian Ingvordsen, whose filmography comprises mostly action movies, takes a conservative cliche – the pernicious effects of degenerate pop culture on vulnerable and immature minds – and turns it into an entertaining cat-and-mouse police procedural. Detective Mickey McCardle (director Ingvordsen) had his career derailed some years ago when he accidentally shot his own partner while pursuing teen serial killer Mark Trax (John Weiner). Trax’s killing spree was inspired by his favourite metal band, The Warriors of the Inferno.

Years later, Trax, who’s given to hallucinatory fantasies of being a sword-wielding hero, escapes from a psychiatric prison and heads for New York. Feeling betrayed by his heroes (the band broke up and its members now have totally mundane jobs), he kills everyone who gets in his way as he seeks the trio out and kills them one by one. At the start of his mission, he hijacks a pickup truck, kills the driver and sets it on fire to make it look as if he himself is dead. The New York police accept this immediately – that is, everyone but McCardle, who senses that Trax is still alive. But he’s dismissed as an unbalanced obsessive and ultimately has to go it alone, against orders, teaming up with punk-scene photographer Garland Hunter (Tiffany O’Brian), who may have caught Trax on film when she was taking shots of a band at CBGB.

What makes the film work is the effective performances of Ingvordsen, O’Brian and, particularly, Weiner, plus the gritty photography of Steven Kaman, much of it grabbed guerrilla-style on the streets of New York before the Giuliani-era cleanup. The movie only falters in the final act, when Ingvordsen’s action roots take over and there’s a protracted, implausible climax which tries to bring together Trax’s heroic sword-and-sorcery fantasies with the resolution of the police procedural.

Once again Vinegar Syndrome have invested quite a bit of effort into the disk. The 2K scan of the original negative looks really good, with a film-like texture and a lot of detail even in the darker scenes. Extras include a commentary track with Ingvordsen, a second track with star Weiner, an on-camera interview with Ingvordsen (with a lot of duplicate information) … and an entire second feature, The First Man (1997), written and directed by Blue Vengeance co-writer Danny Kuchuk. A kind of non-comic riff on Men in Black with echoes of Blade Runner, this features a secret government agency tasked with hunting down and killing aliens living among us. Issues of identity come up with not unexpected revelations late in the story, but Kuchuk can’t quite execute the narrative with clarity or dramatic force; the movie remains a clumsy low budget effort with some interesting elements (further hampered by poor editing which distractingly and unnecessarily uses dissolves so frequently that scenes never gain momentum). Perhaps the most surprising thing about it is the presence of Lesley Ann Warren and Heather Graham in major supporting roles (the latter amusingly paired with Ted Raimi as a newlywed couple).

*

Star Time (Alexander Cassini, 1991)

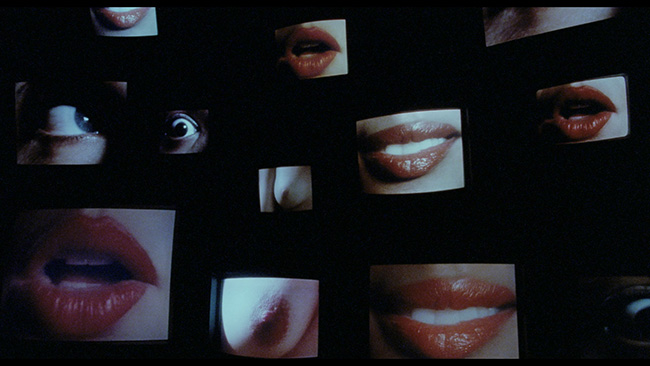

Star Time (1991), the first of only two features by writer-director Alexander Cassini, is a more interesting movie, rooted in exploitation but more experimental in execution. Henry Pinkle (Michael St. John) is a young man with serious issues. He lives alone, occasionally meeting with his therapist Wendy (Maureen Teefy), and his only emotional connection is with the Robertsons, a television sit-com family. By unfortunate chance, just as Wendy goes away on vacation the show is cancelled and Henry becomes totally unmoored. One night, he climbs on the roof of his building and prepares to throw himself off. But at the critical moment a man appears on the roof. Sam Bones (John P. Ryan) is alternately seductive and brutally frank with Henry. He berates him for considering suicide, talks him down and takes him back to an expensive modernist house where he convinces Henry that he can make a difference.

That difference involves supplying the popular culture with something spectacular to talk about – to make a star of himself, in fact, by becoming a flamboyant serial killer. At first, this is difficult; Henry fails on his initial mission, but Bones’ contempt provides the impetus to make another attempt, and he succeeds. Donning a very creepy mask, Henry becomes “the baby-face killer”, a media star as he spreads fear throughout the city.

Cassini blends a satire on the insatiable demands of sensationalist media for provocative material with a more personal treatment of Henry’s psychological issues, his sense of invisibility and a desire to be noticed, to become a star in order to justify his existence. Although shot on gritty Los Angeles locations, the film avoids simple exploitation tactics and takes on a hallucinatory tone which comes from Henry’s twisted view of the world. It’s not always clear whether something is actually happening or is just one of his delusions. Sam Bones is an obvious Mephistopheles-like figure, seducing Henry to the dark side, but just as likely a projection he’s conjured up to justify acting on his own murderous fantasies.

Star Time is more unsettling than the usual low budget serial killer horror movie, artfully directed, with a creepy central performance by St. John, strongly supported by Ryan and Teefy. And that three-quarter baby mask is far more disturbing than Jason’s hockey mask or Michael Myers’ Shatner mask.

The disk includes a commentary from Cassini, a lengthy interview with cinematographer Fernando Argüelles, and Cassini’s first short film, The Great Performance (1983).

Both these Vinegar Syndrome releases resurrect small, little-known movies which deserve greater attention and these Blu-rays go a long way towards justifying this kind of movie archaeology. I’ll have to pay closer attention to the company from now on.

(After writing the above, I picked up a few more VS titles: Glen Coburn’s Bloodsuckers From Outer Space [1984], a regional horror-comedy which sounds like more fun than it is, and Ray Danton’s Psychic Killer [1975], which pre-dates both Brian De Palma’s Carrie [1976] and Richard Franklin’s Patrick [1978] with its story of a man who can project his spirit out into the world to wreak revenge on those who’ve wronged him. Just purchased but not yet viewed: Melvin Van Peebles’ seminal Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song [1971], a key film which helped launch the Black American cinema resurgence of the ’70s, paving the way for such films as Ivan Dixon’s The Spook Who Say By the Door and Bill Gunn’s Ganja & Hess [both 1973], as well as the Blaxploitation explosion which continued throughout the decade.)

*

Four from Arrow Video

I’ve been catching up with some older releases from Arrow Video as well as a couple of more recent titles.

Re-Animator (Stuart Gordon, 1985)

When I first saw Stuart Gordon’s Re-Animator (1985) years ago, I wasn’t terribly impressed. It had a jokey tone, not to mention a degree of sex and violence, which seemed to have little to do with H.P. Lovecraft. It struck me as something which didn’t honour its source, and being annoyingly opinionated back then, I dismissed it.

Fast forward a couple of decades and I decided to take another look, courtesy of Arrow Video’s Blu-ray release … and much to my surprise, I realized it’s a very well-made and effective movie which, yes, does have a slightly jokey tone at times, but in Jeffrey Combs’ Herbert West gives us a classic obsessed scientist so involved in his work that he remains willfully unaware of the dire consequences of his experiments. He’s the kind of guy who will kill a cat so that he can bring it back to life without any apparent awareness that it was perfectly alive before he got his hands on it and now, re-animated, is a monstrous travesty. Naturally when he moves on to human experiments the same thing happens.

Gordon directs very well in this his first feature (thanks, he says in the many extras, to the committed aid of cinematographer Mac Ahlberg); the pace is fast, scenes are constructed for maximum impact, and the gruesome effects are largely convincing and often darkly funny as well as disturbing. In fact, I enjoyed it so much that I’m kicking myself that I didn’t pick up the now out-of-print two-disk edition released last year – that included both cuts of the film, Gordon’s preferred cut and the longer “integral cut”, which includes additional mostly dialogue scenes which flesh out the story. It now goes on-line for really inflated prices, while the single-disk edition I picked up for an acceptable price in a local store contains only the shorter director’s cut, plus most of the extras from the two-disk edition.

Those extras include three commentaries (two from an earlier edition), a one-hour-plus documentary about the making of the film (also from an earlier edition), a discussion of the music with composer Richard Band, an interview with actress Barbara Crampton, a short featurette about Gordon’s roots in the theatre, another with lyricist Mark Nutter about adapting the movie as a musical, plus deleted and extended scenes. It’s a good package, but I regret not having the alternate cut.

*

C.H.U.D. (Douglas Cheek, 1984)

Douglas Cheek’s C.H.U.D. (1984) is an old favourite given new life by Arrow’s excellent hi-def presentation. This is a two-disk set containing both versions of the movie – the longer “integral cut” which includes material not seen in the original theatrical cut which is included on the second disk. This is an excellent low-budget monster movie which belongs to the New York-as-Hell sub-genre from the period; it features artists living in converted warehouse spaces; corrupt government officials willing to sacrifice any number of lives in order to conceal their own bad decisions; homeless people who fall prey to nastiness created by those same officials; and poor people transformed by industrial, chemical and radioactive waste into flesh-eating monsters.

Parnell Hall’s script (from a story by Shepard Abbott) is tight and well-structured, providing creepy sequences in a dank world beneath the city streets, and a collection of characters who have enough life in them to engage audience sympathy. The cast is good, with John Heard as photographer George Cooper, who manages to get evidence of government wrong-doing as he tries to document the lives of the homeless in between reluctantly doing fashion shoots with his model wife Lauren (Brazil’s Kim Greist). Daniel Stern plays it straight (with sarcastic indignation) as a guy running a soup kitchen for vagrants, and the rest of the cast is fleshed out with good supporting players as cops, vagrants and sleazy government bureaucrats. It would make a good double feature with Abel Ferrera’s Driller Killer (1979), which shares its nightmare view of the city.

In addition to containing both cuts of the film (which look excellent), the set has a commentary from Cheek, writer Abbott and actors Heard, Stern and Christopher Curry; interviews with production designer William Bilowit and creature creator John Caglione Jr; and a featurette on the film’s locations.

The Bloodthirsty Trilogy (Michio Yamamoto, 1970-74)

Arrow’s two-disk set of three Japanese “vampire” movies from the early 1970s is a huge upgrade from the region 2 Artsmagic DVD boxed set released in 2004. All three movies look much better, with rich colour and a lot more picture detail. The only extra, disappointingly, is a brief – but enthusiastic – introduction by critic and author Kim Newman, plus three original trailers. I would have really enjoyed an informed commentary or two … or three.

Although all were directed for Toho studios by Michio Yamamoto, The Vampire Doll (aka Legacy of Dracula, 1970), Lake of Dracula (1971) and Evil of Dracula (1974) aren’t actually a trilogy. That is, there are no shared characters, settings or storylines. What they do have in common is an interesting blend of Japanese supernatural elements with a visual style which deliberately calls to mind Hammer horrors (that studio’s Dracula movies were popular in Japan). Like the Hammer films made around the same time, there’s also an uneasy mix of the Gothic with contemporary settings (although Hammer didn’t actually drag the Count into modern London until 1972, in Alan Gibson’s awkward Dracula A.D. 1972).

All three films feature western-style mansions stalked by blood-sucking spirits, with thunderstorms raging outside at night. In the first, The Vampire Doll, a young man named Kazuhiko Sagawa (Atsuo Nakamura) drives to a remote country house to join his fiancee Yûko (Yukiko Kobayashi) only to be told that she died in a car crash a week earlier. The house is occupied by the girl’s somewhat creepy mother (Yôko Minakaze) and a mute servant (Kaku Takashina), who seems on the brink of violence much of the time. When the young man disappears, his sister Keiko (Kayo Matsuo) and her boyfriend Hiroshi (Akira Nakao) trace him to the mansion. They are told that he left after learning of his fiancee’s death, but they are suspicious and manage to get invited reluctantly to stay the night.

They soon discover that Yûko is not in her grave and in fact is lurking around the house with bluish skin and red eyes, looking for blood. Interestingly, prefiguring John Hayes’ Grave of the Vampire (1972) by two years, the girl became a vampire specifically because she was conceived by rape, her father being the local doctor, Yamaguchi (Jun Usami).

The second film, Lake of Dracula, reminds me a little of Jean Rollin’s films, specifically in its use of a haunting childhood encounter with a vampire which hangs over a girl as she grows to adulthood. It also, like much of Rollin’s work, takes place near a body of water which suggests a border between the firm certainty of land and the shifting uncertainty of liquid, between this world and a more ethereal realm. Having returned to the place of her childhood encounter, the young woman Akiko (Midori Fujita) is present when a large crate is mysteriously delivered; inside is a casket from which the vampire (Shin Kishida) of her childhood nightmare emerges. Akiko’s sister Natsuko (Sanae Emi), jealous of Akiko’s relationship with her fiance Takashi (Chôei Takahashi), becomes a willing victim and accomplice of the vampire.

In the third film, Evil of Dracula, Professor Shiraki (Toshio Kurosawa) arrives at an isolated boarding school to take up a teaching position. The Principal (Shin Kishida again) tells him that he is to replace him as head of the school. Meanwhile girls have been disappearing – casually dismissed by the Principal as runaways. The Principal turns out to be a demonic blood-drinking spirit who preys on the girls. Shiraki is told that a couple of hundred years ago, a Christian was shipwrecked in Japan, captured and tortured until he renounced his religion – which turned him into a vampire. Later, the Principal’s vampire wife cuts the face off one of the girls and places it over her own, suggesting that the Principal can do the same and thus the vampire essentially takes possession of each replacement’s identity while continuing to prey on the school’s students.

All three films are moody, visually quite elegant, the western stylistic elements combined with Japanese settings and characters giving them an exotic air. While they are not particularly well-formed – some of the storytelling is vague and clumsy – this exoticism makes them interesting and quite entertaining. They have never had a particularly good critical reputation (Stuart Galbraith IV in his Japanese Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror Films [McFarland, 1994] is almost completely dismissive, although he does allow that Lake of Dracula is better than the movies Hammer was putting out at the time), but Arrow’s fine presentation makes them worth watching again.

*

Images (Robert Altman, 1972)

During Robert Altman’s most creative and productive decade, the ’70s, I perhaps perversely liked best the films which were more poorly received by critics and audiences. I liked Brewster McCloud (1970) way more than M*A*S*H, and I liked Images (1972) way more than Nashville (1975). I still have problems with M*A*S*H and Nashville, both plagued by glib cynicism and a frequent contempt for their characters, but I will admit that Brewster McCloud is something of a mess, with Altman experimenting with more narrative tricks and possibilities than the small and charming fantasy can possibly contain.

Images, on the other hand, is a chilly masterpiece. Shot in Ireland from Altman’s own script, it tries and impressively achieves that difficult trick of inhabiting the point of view of a thoroughly unreliable character. We see the world, and the story’s events, strictly through the eyes of Cathryn (Susannah York, in her career-best performance), a woman slipping inexorably into schizophrenia, unable to separate reality from hallucination and fantasy, although she eventually makes a determined effort to rid herself of all the intimidating phantoms her mind has conjured up.

The sense of dislocation begins immediately. Driving to their remote country house, Cathryn and her husband Hugh (Altman regular Rene Auberjonois) stop at the top of a hill overlooking the house which is nestled in a wooded valley. It’s an appropriately fairytale landscape. As Hugh takes off on foot, eager to get started on some bird hunting, Cathryn looks down at the house and sees their car driving up the lane and stopping out front. And she watches as she, Cathryn, gets out. Altman cuts to the front of the house and Cathryn, about to enter, glances up the steep hillside and sees a small figure standing on the rim looking down at her … herself.

Does everything which follows represent a feverish fantasy Cathryn imagines while standing up there on the hill? Or has she been replaced by a doppelgänger who now lives her life down below? One of the film’s real strengths is that it never sinks to any kind of pat certainty about what is happening. In the house, Cathryn works on the children’s book she’s writing (Susannah York’s own book In Search of Unicorns), which we hear throughout the film in voice over; while Hugh commutes back and forth, going to the city for meetings and returning to hunt, Cathryn is beset by a former lover, Rene (Marcel Bozzuffi), who happens to have died several years earlier. He pops in and out, often at inconvenient times, occasionally morphing into Hugh to further complicate things. But she’s also oppressed by Hugh’s friend Marcel (Hugh Millais), who visits with his daughter Susannah (Cathryn Harrison), who may or may not be Cathryn’s own younger self – at least in her mind. Marcel is a brute who “understands” that Cathryn likes rough sex and puts pressure on her to be his mistress.

Although no linear explication of plot can make sense of the film’s events – does Cathryn actually kill anybody? is it all in her head? … in the experience of watching it, Images unfolds with a rigorous psychological and thematic logic. In this, as many have already noted, it stands somewhat apart from the rest of Altman’s work, which is notable for its loose improvisatory feel. In a typical Altman film, you sense that he was exploring all kinds of possibilities on set and only found a shape for the material once he was in the editing room. Images, in contrast, is a tightly and skillfully constructed work, almost clinical in its detached observation of a disordered mind … but invested with so much life by its committed cast, particularly York in a very difficult role, and expressed through, well, images which are so rich and filled with nuance and detail that it becomes both deeply disturbing and aesthetically exhilarating.

Images was the second of three films shot for Altman by Vilmos Zsigmond, bracketed by McCabe & Mrs Miller (1971) and The Long Goodbye (1973). It’s always seemed strange to me that they didn’t work together again, as this trio are arguably the best films Altman ever made and to some degree that is due to Zsigmond’s superb and often risk-taking cinematography (once again Zsigmond flashed the negative to soften the image and increase contrast, giving it a degree of grain which was unusual at a time when filmmakers were striving for a cleaner, slicker look)..

Although all three of Altman’s “female madness” movies – That Cold Day in the Park (1969), Images and 3 Women (1977) – have much to recommend them, I think Images is the most perfectly realized and most resonant thematically and psychologically. That Cold Day in the Park is still somewhat bound by the crazy lady genre launched by Robert Aldrich’s What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962), while 3 Women is too openly an homage to Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966) to stand fully on its own.

The film looks gorgeous on Arrow’s Blu-ray with an image scanned in 4K from the original camera negative. Extras include a commentary by Samm Deighan and Kat Ellinger, and a partial commentary by Altman from MGM’s earlier, inferior DVD release. Also carried over from the DVD is an interview with Altman and Zsigmond. New to Arrow’s release is an interview with actress Cathryn Harrison and an appreciation by Stephen Thrower.

Comments

I’ve got The Bloodthirsty trilogy on my Amazon Wish List, I’m watching the price fall while I order some other things first. I enjoyed all the movies in the set, Sperhauk brought them to Friday Night Movie night and I would want to watch them again someday. I liked their look. I thought they captured the Hammer look while still making it their own thing. I agree the story is lacking, they could have used a Japanese Jimmy Sangster.

I’ve gotten a few Arrow Blu-rays of late, The Nikkatso Diamond Guys 1 & 2, already seen the movies from Netflix and wanted a set to re-watch. I ordered the 2 Seijun Suzuki early film sets sight unseen but haven’t got to them.

Excited this week about the arrival of The Sweeney collected series DVD. I liked that show in the 70s when it was on Canadian TV and I’m finding it entertaining now. The first episode has Brian Blessed as the criminal and he never shouts or gets loud. Blew my mind.

I’ve got a small stack of Arrow releases I haven’t managed to get to yet, including the Outlaw Gangster VIP set, Fukasaku’s New Battles Without Honour and Humanity, Miike’s Black Society Trilogy … even their Taviani Brothers set. I need to win the lottery so I can retire and watch movies!

I love The Sweeney. Bought the Network Region 2 box set years ago and spent weeks binging. Also have the original pilot movie Regan on a Network DVD …

None of those Arrow films are on my wish list but who knows. There’s only so much eBay money coming in so I’ve got to triage what gets bought first. I keep hitting the used stores to pick up popular things cheap, helps support the odder titles and such. We’re lucky in Minneapolis to have a chain called Half Price Books, they have a big DVD/Blu-ray section. All the stores have a clearance section that often turns up great movies at $2-3 each. Good source to find popular movies that you want to see but don’t want to buy at normal release price. I use the library for that reason. One of the guys I know mentioned Bad Day To Go Fishing and I got it from the library. Hopefully will watch it today or tomorrow. It has to go back Tuesday.

I got The Sweeney Network DVDs from the UK, they were cheaper than the US versions. I watched Regan first but it’s not until they get to the series that the cynicism really kicks in. I love the way his bosses throw him into the mix to stir things up. Then casually mention that they don’t have a care what happens to him. I think Regan gets even harder as he goes along. I certainly wouldn’t want to know the guy, better to see him on TV. I’ve got the two Sweeney movies to watch when I get done the series. They actually came out between the 3rd and 4th series so I’ll watch them then.

The Sweeney was quite radical when it first aired. Up until then, cops on British TV were always the good guys; maybe there was a bit of an American influence when The Sweeney was created (Brit police had never been running around waving guns before), but it has a great gritty flavour and Regan is a terrific anti-hero (for whom things don’t go too well towards the end of the series).

There’s a small used music and movie store at Grant Park which has been bringing in more new releases lately (at surprisingly lower prices than the few mainstream stores), and I’ve started buying a few used disks (which for some reason I’ve previously been reluctant to do). Even found a copy of the 3D Blu-ray of Arch Oboler’s The Bubble last week which I went over to Steve’s to watch on Friday. Pretty dull movie, but the “Space-Vision” 3D is really impressive.

If you haven’t seen Fukasaku’s yakuza movies, you should definitely check them out.

There’s a used DVD store in Winnipeg that I went to when I saw you guys a couple of years ago. It’s on Henderson Hwy near McLeod and they had a lot of used DVDs at prices that were OK. I assume they are still there. I do buy a lot of used DVDs and have had little problems with them. I’m fussy and don’t take scuffed or scratched discs. You just don’t see stuff from the smaller video companies much. Mind you, I think that’s to be expected, people who buy films from Arrow, 88 Films, Vinegar Syndrome and the like aren’t as likely to sell those off. Not like the hot action film or comedy.