Back to the future: 2001 revisited

The last time I saw Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey in a theatre was on HAL’s birthday – January 12, 1992. That was at the Cinematheque here in Winnipeg (not a huge screen) and the print was in rough shape, with scratches and damaged frames and the colour shifted drastically towards red. So it was interesting to see it again yesterday on an IMAX screen in its 50th anniversary limited re-release.

When something has become familiar through many repeat viewings on home video, it’s easy to forget its intrinsic power as a theatrical experience. This is particularly true of a film like 2001, which was conceived as a spectacle. When it was first released, many critics were put off by this fact: not only was the film thematically enigmatic and structurally unconventional, its lingering attention to images seemingly for their own sake was considered a dramatic weakness.

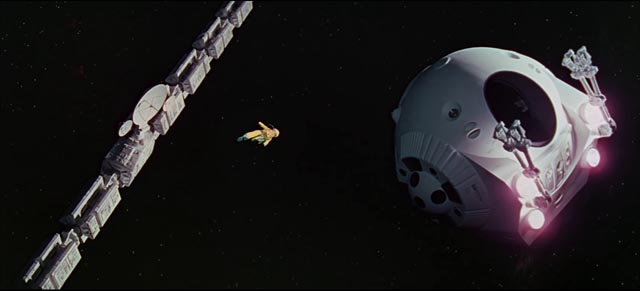

What eventually came into focus – and was abundantly clear last night – was that Kubrick’s intention simply wasn’t conventionally dramatic. He was using all of his mastery of film form to create an experience, not a narrative. This was something I understood instinctually when I first saw it in 1968 at thirteen or fourteen: a year before Apollo 11 made its trip to the moon, Kubrick made me feel what it would be like to actually be in space. His images evoke the vastness, the isolation, the fragility of a human presence in an endless void – no roaring engines, no whooshing spaceships making fast and implausible manoeuvres (like almost every film since), no sound at all except the torturous breathing of the crew in their claustrophobic suits.

Visually, 2001 is about the grandeur of the universe; narratively it is about the smallness of that universe’s human inhabitants. Kubrick has often been seen as a cynic, or at least a pessimist, but it has always appeared to me that he is really a disappointed optimist – someone who expects better of us and is frustrated that we always seem to fall short.

In the opening section of the film, the Dawn of Man, proto-humans live in harmony with other animals in a sun-baked African landscape. An alien force in the form of the famous black monolith arrives to intervene, somehow boosting the mental capacity of one pack of apes. These creatures are given an understanding of tools, a crucial development in their evolution towards us … and they immediately use those tools as weapons, first to kill other animals for food, then to attack a rival pack, killing its leader.

Then comes the famous jump cut from a bone tossed skyward in triumph to a satellite orbiting Earth in 2001 (although it’s never mentioned in the film itself, this satellite was intended to be a weapons platform). In the lengthy trip to the moon taken by scientist Heywood Floyd (William Sylvester), we immediately get a strange sense of disorientation – Kubrick emphasizes the grandeur of our technological achievement (the lyrical dance of the spaceship and the rotating space station) in contrast to the triviality of human activity: Floyd naps on his Pan Am cruiser, his pen floating weightless beside him; crew suck liquid concentrated food from plastic trays.

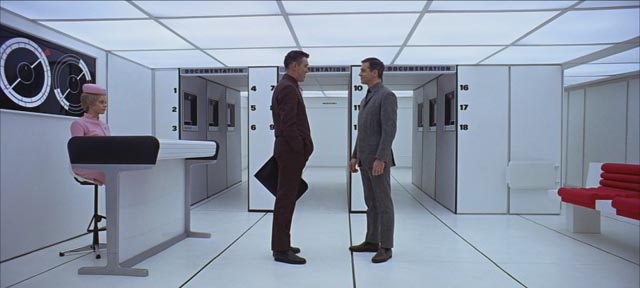

And most importantly, Floyd makes a banal personal phone call from the space station to his young daughter and chats about her upcoming birthday as the Earth swings past the window beside him; and he stops for a moment to chat with a group of Russian scientists who ask what the heck is going on at the American lunar base. Although narratively, this lets us know that something mysterious is happening on the moon, what is most important about the exchange is a pointed refusal to communicate, signalling that the tribalism we witnessed among the apes has followed us through millennia of development. We still suffer from distrust and paranoia and it undermines our capacity to respond effectively to the grandeur we take all too much for granted.

This fundamental weakness ultimately infects the most sophisticated tool we have yet created; the artificial intelligence of HAL 9000 (voice of Douglas Rain), the computer brain which controls the Discovery on its journey to Jupiter to seek the recipient of the signal emitted by the black monolith which has been uncovered on the moon. Ironically, HAL is the only (conscious) one on board who knows about the signal and the purpose of the mission, and he becomes paranoid about the two men who see to the running of the ship – Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea) and Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood), who, like Floyd, go about their business with technocratic banality. Tribalism extends here to man versus man-made machine.

After HAL kills Poole and Bowman lobotomizes HAL, the lone surviving human encounters the alien force again in orbit around Jupiter. The film’s final section is its most enigmatic, beginning with the extended lightshow of the Stargate through which Bowman travels and ending in what appears to be a facsimile of a 17th Century room, where Bowman watches himself grow old and ultimately be reborn as the sentient Starchild, a baby with probing eyes, encircled by bright light, which in the final image finds itself floating above Earth and looking down inscrutably.

The alien force has pushed us once again, but Kubrick leaves it open as to whether this time we can move beyond the self-defeating tribalism and violence which has threatened our survival. In that open-ended ending lies a glimmer of hope that perhaps we can be better after all …

This question runs through much of Kubrick’s work, from Paths of Glory through Dr. Strangelove and A Clockwork Orange, to its fullest and most chilling expression in Full Metal Jacket. But all of those films adhere to a human scale, while 2001 expands the theme to encompass all of human history.

2001: A Space Odyssey remains virtually unique among science fiction films. Despite the enigmatic narrative and thematic content, Kubrick applied his fastidious attention to detail to every aspect of the film. The technology may look dated and somewhat rudimentary to the modern eye, but it was firmly rooted in the technology of its time – rather than striving to be “futuristic” (the NASA technology which put astronauts on the moon looks equally primitive now). This means that 2001, like so much of Kubrick’s work, has a powerful air of authenticity, all the more so because of the mundanity of the characters and their interactions. This is a lived-in world rather than one of high adventure; as already mentioned, the disparity between the awesome scale of the universe and the blandness of the characters is deliberate, indicating the ways in which our limited grasp shrinks something which is far too large for us to comprehend.

Whether serious or pulp, almost all subsequent science fiction movies concentrate more on thrills and action than a contemplation of the relationship between us and the cosmos. Tarkovsky’s Solaris is an obvious exception, but one which focuses more on human experience in response to unknowable cosmic forces, while Kubrick is ultimately more interested in the cosmic rather than the personal.

While it was possible to feel the grandeur of 2001 once again on the IMAX screen, I have to say that I really wished I’d had an opportunity to see one of the new 70mm film prints rather than the 4K digital version. Digital lacks the clarity of large format film and the image was often softer than it should have been. And sadly, although I and my friends went to the first-night screening of a one-week run, there were only about two-dozen people in the theatre, many of the audience as old as us. Perhaps after decades of Aliens and Star Wars, there aren’t many left who can really appreciate what Kubrick achieved.

Comments

I had a great time watching 2001 at iMax. Watching 2001 on the big screen is not at all like watching it on BluRay, even on a 56 inch screen. I got goose bumps when the opening credits started. I was wonderstruck through the entire movie.

I think I mentioned to you that I’d watched 2001 twice in the weks before seeing it in iMax, and that I’d somehow, strangely, managed to get involved in the drama of the characters. All that went out the window while watching it on the big screen. I think you are right. It is sheer spectacle.

I’ve always wondered why I experience a total Sense of Wonder while watching 2001, yet yawn while watching Star Wars or its sequels. Your post explains why.

I saw 2001 for the first time when I was eight years old, with my brother who was six. We were dropped off at the theater by my dad. For both of us, it has remained one of the most profound movie experiences we have ever had. Even if that ‘profoundness’ didn’t extend much past ‘Wow, cool space apes! Wish I had a bone that turned into a spaceship!’ at the time.

It was also interesting to see it with my daugher (29), who had never seen it before in its entirety. Actually, as she admitted, she’d never stayed awake past the docking of the Pan Am shuttle with the space station. Yet, she really enjoyed the whole movie while seeing it in the theatre. Again, I think it was the spectacle of the presentation.

My brother went to see it this week, too. He tried to get me to go with him, a kind of 50th anniversary viewing, but I missed his email. Wish I’d gone again. I waited forty years to see 2001 in the theatre again (I saw it repeatedly in 70mm on a Cinerama screen in the 70s); I’m thinking now I’ll take advantage of any opportunity that comes my way.

An exceptionally memorable 1968 movie experience at the Garrick(?)Theatre, now a parking lot across from the Marlborough Hotel. Many details still fresh after 50 years.

My foolish 20 year old self recommended it to my 55&56 year old parents. They both slept through most of it.

I never recommended another movie for them.