Robert M. Young’s The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez (1982): Criterion Blu-ray review

I have no idea why I had never seen Robert M. Young’s The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez (1982) before its release on Blu-ray from Criterion. I do vaguely remember hearing the title back in the early 1980s, but given the very limited release the film received from Embassy Pictures, chances are it never reached Winnipeg. (Producer-star Edward James Olmos recounts that story with some bitterness in an interview on the disk; he says that the man in charge of distribution at Embassy was hostile to the film and deliberately sabotaged the release.) Thus a film which is historically important for a number of reasons fell through the cracks; this restored version should finally gain it the wider recognition it deserves.

Based on an actual incident in Texas in 1901, The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez is on its surface a western chase narrative – a man on the run, various posses vying to capture or kill him. But its true subject is racism and the way it permeated (and still permeates) American society. Texas, taken from Mexico in war, contained two cultures not simply side-by-side, but inextricably woven together. The Mexican farmers working the land were looked down on contemptuously by their white American neighbours.

The film opens with a report that one such farmer, Gregorio Cortez (Olmos), has shot and killed Sheriff Morris (Timothy Scott). That incident is returned to repeatedly throughout the film, recounted by a number of different people whose perspectives differ in significant ways. There is no doubt that Cortez killed the Sheriff; the uncertainty lies in why it happened, and that we only learn gradually.

During the chase, the posses terrorize and kill a number of Mexicans – some mistaken for Cortez, some suspected of harbouring him or having knowledge of his whereabouts. The brutality of the white pursuers is rooted in their reflexive sense of their own superiority, of their contempt for those they consider less than. But even these incidents are complicated by differing accounts. The death of another man during a nighttime raid on a farmhouse is attributed to Cortez, but later it becomes clear that the raid was a chaotic mess because the members of the posse had been drinking and were shooting wildly, the man probably killed by one of his fellows.

Cortez flees across country, first north, then turning south and making for Mexico. The chase becomes the biggest manhunt of the era, involving local lawmen and a large number of Texas Rangers (an organization fighting to justify its own existence at the dawn of the 20th Century). But after two weeks of running, Cortez essentially gives up – he arranges for an old Mexican to turn him in and collect the reward. Taken alive, he is put on trial for first-degree murder (although townspeople attempt to lynch him before the trial).

This is where the incident’s historical importance is fully revealed. Given a reluctant defence attorney, who through an interpreter gets Cortez’ account of the original killing, the farmer’s case is heard in a court which for the first time in American judicial history included interpreters who could bridge the barrier of unshared languages. And, it turns out, the entire incident hinged on what amounted to a misunderstanding of a single word. Sheriff Morris’ deputy, acting as interpreter, simply didn’t understand a subtle distinction Cortez made between male and female horses when the sheriff came to question him about whether or not he had been involved in a possibly illegal trade. Because the deputy, Boone Choate (Tom Bower), misunderstood, Cortez’ denial was seen as resistance, prompting the sheriff to try to arrest him at gunpoint …

Although the killing was undeniable, the motive was in dispute and the (white) jury refused to convict on the original charge of first degree murder. There were subsequent appeals, retrials, and years in prison, but Cortez was not executed – which at the time was a remarkable thing for a Mexican who had killed a white man.

Adapted by novelist Victor Villaseñor from a 1958 book by journalist and scholar Américo Paredes called With His Gun in His Hand, which recounted the history of the popular ballad and folklore which resulted from the case, the film has a subtle non-linear structure which builds the narrative in layers to give the story a richness and air of authenticity, rooted in reality yet growing towards heroic myth. Few westerns can claim the attention to period detail which makes The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez feel at times like documentary (not surprising given director Young’s background as a documentarian). While gradually transforming Gregorio Cortez from a simple farmer into a folk hero, the film never romanticizes him, maintaining a powerful sense of realism.

One aspect of that realism is crucial to the way the narrative works. The filmmakers chose to leave all Spanish dialogue unsubtitled (a decision honoured by Criterion). For an English-speaking audience, any understanding of what the Mexican characters say is mediated by on-screen characters who we learn cannot be fully trusted. Only when Cortez’ lawyer asks Carlota Muñoz (Rosanna DeSoto), a Mexican activist, to interpret for him do we finally understand what really happened during the encounter with Sheriff Morris. But by that point, we have come to know that these two cultures are separated by different ways of seeing the world rooted in their different languages. The issue becomes one’s willingness to be open or not to the other. In one sequence, Cortez receives hospitality from a rancher who provides him food and a place to camp for the night in exchange for an opportunity to talk, even though he knows Cortez can’t understand him; the simple fact of companionship is enough to ease loneliness for this man. But at other times, an inability to speak English is excuse enough to beat or even kill a man. (Interestingly, a bilingual viewer would know from the start that the shooting was rooted in a mistranslation, giving them a quite different experience of the narrative.)

The Rashomon-like structure of the film is enabled by the presence of newspaperman Blakely (Bruce McGill), who joins the hunt and questions various members of the posse – including deputy Boone Choate – and reports back by telegraph, providing a running commentary which itself is rooted in misunderstandings and distorted accounts (Cortez is for a time transformed into a “gang of Mexicans” terrorizing the country). In this, the film seems prescient of our current media-saturated environment where moment-by-moment reporting conveys unreliable information which spreads misunderstanding. Ironically, the ballad created in the moment – a corrido written to spread the story among Mexicans even as it happened – provided a more accurate account of events even as it elevated Cortez to folk hero.

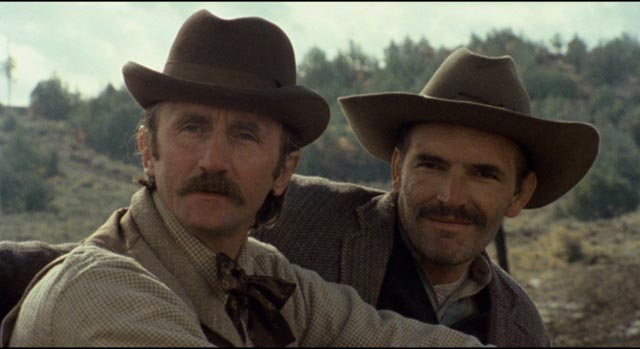

With its authenticity and its revisionist approach to a familiar genre – particularly in the transformation of the central Mexican character into a hero confronting an oppressive white society, in contrast to the cliched bandito of conventional westerns – The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez has a freshness and energy which make it an exhilarating experience. The cinematography of Reynaldo Villalobos combines spectacular landscapes with a subtle attention to faces and the textures of sets and objects, giving the film a visceral quality, a strong air of physical presence. Director Young frequently uses a handheld camera to catch action on the fly and some of the stunt work is breathtaking (there’s a superb shot using a long lens to capture two riders on a dry riverbed as they switch horses in full gallop before racing past the camera).

In theme and technique, the film feels completely undated; in fact, it takes on a new sense of urgency given the current political climate in the States, with its reminder that Mexicans are not alien to the country but rather have been a part of the cultural fabric for a long time – in fact, the U.S. took large swaths of land from them, just as it did from Native Americans. The current widespread hostility to “immigrants” is rooted in the same arrogance combined with fear which motivated the events depicted in the film.

*

The disk

For the new 2K transfer (funded by the Academy Film Archive, with a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts), the original raw Super-16 negative was scanned and then conformed to match Edward James Olmos’ personal 35mm print. The restoration has a rich film-like texture, with earth tones predominating.

The soundtrack provides equally authentic ambiences and effects, and dialogue is clear. If anything might date the film, it’s the score by W. Michael Lewis and Edward James Olmos, which is composed around the original corrido but uses a synthesizer rather than instruments (the limited budget made an orchestral score prohibitively expensive); but despite the out-of-period electronic element, the music does complement the visuals quite well.

The supplements

Criterion have included three informative extras on the Blu-ray, beginning with a new interview with producer-star Olmos (27:55), in which he discusses the importance to him personally of telling this story, how the film was made outside the mainstream, and his and Young’s initial efforts to find its audience – efforts subsequently sabotaged by distributor Embassy – and how the production helped to pave the way for independent film production at a grassroots level.

There’s a new interview with Chon A. Noriega, author of Shot in America: Television, the State, and the Rise of Chicano Cinema (19:02), in which he discusses the original corrido, the rise of Chicano cinema in the ’80s, and the film’s relation to and transformation of the western.

Finally, there’s a panel discussion from 2016 (23:02), featuring Olmos, director Robert M. Young (now in his 90s), producer Moctezuma Esparza, director of photography Reynaldo Villalobos, and actors Bruce McGill, Tom Bower, Rosanna DeSoto and Pepe Serna, all of whom reminisce about the experience of making the film.

The booklet essay is by film historian and academic Charles Ramirez Berg.

Comments

I missed this too.

It left me haunted and yes, it is relevant to current events!