The pleasure of not knowing

My relationship to movies has changed so radically over the past four decades that it’s difficult to recapture what it was like when the movies meant going to the theatre (in the 1970s in particular going multiple times in a week), supplemented by whatever showed up on television (pan-and-scanned, chopped to pieces for commercial breaks). A couple of times a year I get together with a small group of friends to chat about what we’ve seen recently, and one of these friends has suggested that we all dig into our memories and try to recall the particular movies which had some kind of impact in our formative years (say 5 to 18) – not necessarily films we now recognize as landmarks and masterpieces, but ones which connected with us personally in some way.

That’s a tough call for me as, given the way my brain works, it’s a lot easier to identify those movies seen a bit later which helped me build a conscious understanding of cinema as an art form. In fact, I can identify the specific year when that happened, thanks to a cluster of movies which triggered thoughts about how film works on me as a viewer: that was in 1973. I can even name the movies which formed the core of that awakening: Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets, Terrence Malick’s Badlands, James William Guercio’s Electra Glide in Blue and Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now. These were all movies in which the techniques of filmmaking dovetailed with the construction of meaning and the triggering of powerful emotional responses.

Of course, that’s been true of movies since their earliest days and I can watch silent movies, film noirs, westerns, war movies, mysteries, comedies and a romance like Casablanca now and parse the ways in which the filmmaker’s skill creates a multi-layered experience for me. But those four films, all seen within a few months in 1973 were the cinematic Rosetta Stone for me.

Back in those days, the simple act of going to the theatre required that one be willing to give oneself to the experience. That’s the biggest change over the ensuing decades. With increasing accessibility, first with tape, then with disks and now with the ubiquity of streaming, the experience of movie-watching has been diminished even as opportunities have increased. When you can watch a movie on your phone, surrounded by an endless flow of distractions which constantly pull your attention away, your relationship with the movie is fundamentally different from when you’re sitting in the dark focused on the screen. Even the latter experience has changed almost beyond recognition as theatres vie for your attention in competition with all the other options available. The movies themselves are almost secondary to the “experience” of the theatre with its reclining seats which move and vibrate “to put you in the movie”, with the meals you can eat while you’re sitting there, the interactive games you can play on your phone before the trailers begin …

Only in the privacy of my own space can I get even an echo of that personal connection between me and the shadowplay on screen – though that too is diminished because there are too many possible distractions even in the darkness of my living room, and the screen itself is so much smaller.

But while the actual viewing experience has been compromised by changes in technology, access has been expanding radically. Back in the day, the problem was that you’d read or hear about some movie that you might not get an opportunity to see. But now, you have the opportunity to see far more than you can find time for. (My own privileged burden is a collection of thousands of movies on disk, quite a few of which I just haven’t had the time to watch yet – and I’ll no doubt be dead long before I get through them all because I’m constantly adding to their number.)

A corollary to this expanded access is the explosion of information about movies on-line. And the downside of that is that it has eaten away at the possibility of surprise and discovery. It’s possible to find information on-line about anything that’s been, or is about to be, released and you get the feeling that you already know a film before you actually see it. This is something I’ve brought under control to some degree in recent years – simply by avoiding reviews of anything I haven’t seen yet. I subscribe to email newsletters of various companies I know will point me towards things which I’ll find interesting, but even then I try to minimize what I read about them. Criterion, Indicator, Severin, Arrow, Shout! Factory, the BFI and a few others regularly release titles I’d like to check out … and Amazon’s suggestions occasionally point me towards something worthwhile. No doubt I’m missing out on all kinds of things which I’d like if I came across them, but I still find more than enough to keep me busy.

Having built a slightly porous firewall to filter out a lot of the noise, I’ve managed to regain some small degree of surprise and discovery. Most recently (apart from a few disks I’ve stumbled across browsing in a local store), my happiest “accident” came as a result of Arrow’s newsletter. A couple of months ago they announced a Blu-ray release of a movie I’d never heard of – The Endless (2017) – by a pair of directors I’d never heard of – Justin Benson and Aaron Moorhead. The brief blurb in the email prompted me to watch the trailer, and that was sufficient to make me place an order without knowing anything more about the movie. I was only vaguely aware that the film came with a companion feature, Resolution (2012), and it wasn’t actually until I watched the disk that I realized that both features exist in the same narrative world, share characters, and illuminate each other.

Having watched both movies now, plus all the extras on the disks, I realize that I’d actually seen the Blu-ray of the pair’s second feature, Spring (2014), on store shelves a couple of years ago, but the brief impression I got at the time was that it was some kind of New Agey romance (which it apparently isn’t) and didn’t look any further. I’ve also seen an early short without registering who made it, one of four segments of V/H/S Viral (also 2014), in which some skateboarding jerks run into threatening manifestations of the Day of the Dead on the border at Tijuana.

But having come to The Endless and Resolution by chance, I’ve discovered filmmakers whose work really appeals to me. Rather than big effects and large-scale action, they make genre films rooted in well-drawn characters and subtle suggestion – kind of like modern-day Val Lewtons and Jacques Tourneurs. Having met and hit it off as interns for Ridley Scott’s production company, Benson and Moorhead use the possibilities of digital filmmaking to make small, hand-crafted movies which evoke an expansive narrative universe which draws on genre traditions going back to the likes of H.P. Lovecraft and M.R. James.

*

In The Endless, two brothers struggle to make ends meet by cleaning houses. A decade earlier, they had left a cult, and now outside of work they attend deprogramming sessions which are required for them to continue receiving some kind of financial assistance. This life is controlled by the older brother, Justin (played by writer/co-director Benson); but his efforts to hold things together frustrate the younger brother, Aaron (played by Moorhead), who was young enough when they left the cult that he has mostly positive memories. Justin tells him horror stories about the life they led there, supposedly awaiting the arrival of an extraterrestrial messiah (one of the things he says is that all the men in the cult were castrated to limit unnecessary distractions).

At the start of the film a package arrives by courier, containing a videotape in which one of the cult members says the ascension is imminent. Justin views it as a kind of suicide note, a declaration that the cult members are about to take drastic action, but for Aaron it exerts an irresistible pull and Justin finally, reluctantly, agrees that they can pay a visit, just for a day, hoping that this will finally erase Aaron’s fond memories.

When they arrive at the compound, they are greeted warmly, fed, served beer from the commune’s own brewery, and Justin finds Aaron’s attachment being reinvigorated. There are communal meals, campfire get-togethers, games … and Aaron urges Justin to stay just a little longer. But it’s denied that the tape was sent by anyone there and slight but strange things begin to happen, suggesting that the brothers have been lured back for inscrutable reasons. Benson and Moorhead are very good at undercutting a genuinely amiable surface with hints of something increasingly dark – shadows and movements at the edge of the frame, noises which indicate the presence of something unseen – which infuses the film with a deepening aura of menace. As these things gain momentum, it seems that “the ascension” is quickly approaching … but it isn’t what it initially appeared to be.

The entire community is caught in a kind of time loop, remaining permanently at the same age they were when Justin and Aaron left, facing over and over again a catastrophic reset, trapped in a narrative which leaves room for some variation but is mostly some kind of eternal cycle of reruns controlled by a malevolent force which seems to be toying with the cult members for its own entertainment.

The film begins with a text card quoting H.P. Lovecraft, suggesting that his nebulous supernatural entities are behind these events, but Benson and Moorhead never actually reveal the entity responsible. In this, The Endless reminds me of Chad Crawford Kinkle’s equally creepy Jug Face (2013), which also has distinct Lovecraftian undertones.

Having watched The Endless, I moved on to Resolution and discovered that it’s set in the same narrative world, but at a time when Justin and Aaron were still in the cult (there’s a brief scene in which the brother’s encounter the earlier film’s protagonist, a moment seen in flashback in the later film). This is a smaller film, but it shares the same understated air of unseen menace and focus on characters caught up in inexplicable events.

Michael (Peter Cilella) leaves his pregnant wife to go visit his childhood friend Chris (Vinny Curran), who is squatting in a remote, derelict cabin (which happens to be near the cult’s compound), slowly killing himself with meth and other drugs. Michael is determined to convince him to enter rehab, but Chris sees no point. So Michael chains him to a wall with handcuffs and settles down to help him go cold turkey.

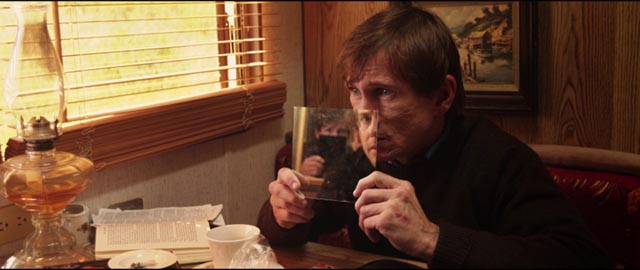

As they spend a week together in this squalid setting, Michael’s arguments for intervention and Chris’ resistance going in circles, they are menaced by a pair of drug dealers pissed off at being cheated by Chris, by a man from the reservation on which the cabin happens to be, and less concretely and more disturbingly by strange “messages” which keep turning up in various different media – a battered library book, a videotape, an old hard drive which Michael digs up, a warped vinyl disk – messages which refer to the friends’ past and, gradually, to their future (the latter seemingly a warning of their impending violent end).

It becomes apparent that these messages are being sent by a force which is manipulating their own story – the same force which has trapped the members of the cult.

Without in the least becoming self-consciously “meta”, both films work on an immediate level as quietly disturbing supernatural horror, but more deeply they are meditations on the nature of storytelling in which characters are initially being moved by an unseen author, but gradually become aware of their role in the constructed narrative and begin to take action to change the course of the stories they are trapped in.

Benson’s scripts for both films seem relaxed, almost effortless, yet are tightly structured, and Moorhead’s cinematography is clean and devoid of stylistic affectation. Both films have an unforced naturalism which gives impact to the supernatural elements – again, reminiscent of Val Lewton’s movies in the ’40s. Performances are uniformly good (though if I had to point out a single weakness it would be that Vinny Curran doesn’t get increasingly grungy as the days of his captivity go by).

I’m really glad that I came to these movies with virtually no prior knowledge and was able to experience them without preconceptions. Immediately after watching them, I ordered a copy of Spring … and regret that there’s only this one other movie waiting to be seen.

Arrow’s two-disk Blu-ray set presents both films in pristine HD masters with commentaries on each disk along with a variety of interviews, deleted scenes, outtakes and various other ephemera.

Comments