I love a deal …

I’m a sucker for deals, so like any “good consumer” I’m inordinately attracted by sales. Although I’m aware that this makes me a bit of a sucker – I end up spending a lot of money I’d be better off holding on to – I still can’t resist. And the Internet magnifies the problem manyfold. Which explains why I went overboard this summer with two big on-line orders to Arrow and another to Severin. The big problem (apart from spending too much money) is that this adds considerably to my viewing backlog and the uneasy feeling that I can never ever get around to watching all the movies I own.

I’ve barely made a dent in the Severin pile – of eleven disks, I’ve so far watched only three: Jess Franco’s Count Dracula and The Hot Nights of Linda, and D.B. Benedikt’s Beyond the Seventh Door. Still waiting are Buddy Giovinazzo’s Combat Shock (an upgrade from Troma’s excellent DVD edition, and the reason I originally placed the order); a Barbara Steele triple-bill, Mario Caiano’s Nightmare Castle, Antonio Margheriti’s Castle of Blood and Massimo Pupillo’s Terror Creatures From the Grave; Franco Prosperi’s Wild Beasts (an upgrade from Camera Obscura’s Region 2 DVD edition); Marino Girolami’s Doctor Butcher M.D. (a two-disk edition which includes the original Zombie Holocaust cut, plus a handy vomit bag); Rod Hardy’s Thirst, an Australian rethinking of vampires with a socio-political edge; Mariano Baino’s Lovecraftian Dark Waters (an upgrade from No Shame’s special edition DVD); Sheldon Renan’s The Killing of America, a shock documentary about the violence inherent in U.S. culture (including the longer Japanese cut as well as the American release version); and last, and no doubt least, William A. Levey’s Blackenstein.

I’ve been doing a bit better with the Arrow stack, although there are more of them – with five more pre-orders due this month: Pascal Laugier’s Incident in a Ghostland (shot here in Winnipeg, with my friend Gord as production designer), Teruo Ishii’s Horrors of Malformed Men (an upgrade from the Synapse DVD), Flavio Mogherini’s The Pyjama Girl Case (a kind of Australian giallo), Ted Post’s The Baby (a twisted-family thriller from the 1970s), and Tomu Uchida’s Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji (a samurai “road movie” from 1955 which sounds as if it’s a precursor to the Zatoichi series).

Still to be watched are Takashi Miike’s Dead or Alive trilogy, Hirokazu Kore-Eda’s The Third Murder, Sergio Martino’s The Suspicious Death of a Minor, Lucio Fulci’s Don’t Torture a Duckling (an upgrade from Anchor Bay’s DVD), Roger Donaldson’s Sleeping Dogs (also an upgrade from an Anchor Bay DVD), Vincent Ward’s Vigil and The Navigator, Geoff Murphy’s The Quiet Earth (hmm, there’s a pattern here; upgrade from the Anchor Bay DVD), Abel Ferrara’s The Addiction, Amat Escalante’s The Untamed, and Jörg Buttgereit’s Nekromantik and Nekromantik 2. I hope to watch (and write about) many of these over the next couple of months, but for now I’ve viewed seven Arrow disks in the past couple of weeks.

*

Maniac Cop (William Lustig, 1988)

The first of director William Lustig’s collaborations with Larry Cohen is, like the rest, an unabashed exploitation movie which courts offence with graphic violence and a seedy urban tone. Knowing that the two sequels feature a murderous zombie cop, I was a little surprised that this first in the series has no overt supernatural elements at all. A big man in a police uniform is killing random New Yorkers and a young patrolman (the inimitable Bruce Campbell), while cheating on his wife, is framed for the killings. He has to break out of custody to solve the case himself before it’s too late.

The killer, a brutal cop who was sent to prison for acts of violence and not surprisingly attacked in the showers by other inmates, is essentially a braindead hulk being manipulated by his old embittered girlfriend to get revenge on those she sees as responsible for ruining their lives. Cohen’s usual touch with characters is evident, though the grim tone doesn’t leave a lot of room for his signature humour, and Lustig stages events effectively, making good use of New York locations.

The disk image looks as good as you could expect of a low-budget ’80s B-movie, and it features interviews with actors Tom Atkins and Laurene Landon and writer-producer Cohen. (Too bad Bruce Campbell is missing.)

*

The Car (Elliot Silverstein, 1977)

Elliot Silverstein worked for years in television before making his feature debut with Cat Ballou in 1965. That slight comedy western was an unexpected hit which won an inordinate number of awards, most notably an Oscar, a Golden Globe, a BAFTA and a Silver Bear for Lee Marvin as best actor. Silverstein made only four more features in the next decade before returning to television, and there was no discernible pattern in his choices of material – a “counter-cultural” comedy (The Happening), a serious western (A Man Called Horse), a sadistic thriller (Nightmare Honeymoon) … and this absurd horror movie, The Car (1977), dubbed by many “Jaws on wheels”.

James Brolin is sheriff of a small Utah desert town whose inhabitants find themselves being stalked by a menacing black sedan which appears to have no driver. As the car races around running people over, knocking them off bikes, and eventually crashing through houses, the sheriff and his men have to devise a trap in a nearby canyon. Lured to its “death”, the car explodes, apparently releasing a demon in an apocalyptic cloud of smoke.

Everyone seems to be taking all this seriously, but no amount of technical polish can really overcome what is an undeniably dumb concept. Which is not to say that The Car isn’t entertaining – probably best watched at a party with plenty of beer and enthusiastic companions.

The transfer is very good and the disk features a commentary from director Silverstein and interviews with special effects artist William Alridge and actor John Rubinstein, plus a Trailers From Hell commentary by John Landis.

*

Burnt Offerings (Dan Curtis, 1976)

I didn’t think much of TV impresario Dan Curtis’ first real theatrical feature (he’d previously made two big screen offshoots of his long-running Dark Shadows soap opera) when I saw it in 1976. But then I hadn’t been much impressed by Robert Marasco’s novel when I read it – it seemed pretty insubstantial compared to other literary horrors of the period (Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby, William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist, Tom Tryon’s The Other and Harvest Home) – and the movie seemed to have the cramped feel of something made for TV.

But watching it again forty-odd years later, I enjoyed it more. It’s not in any way original – a middle-class family (mom, dad and young son, plus aging aunt) rent a big country house for the summer at a ridiculously low price only to find themselves succumbing to supernatural forces – but Curtis handles things efficiently if not with any particular stylistic flair. I think on this viewing, I was predisposed to be tolerant because I immediately recognized the house as the Morningside funeral home from Phantasm (the Dunsmuir house in Oakland, California).

Rather than a haunting, Burnt Offerings suggests that the house itself is alive and feeds off its residents. Like the Overlook Hotel in The Shining, it finds those characters’ weaknesses and preys on them. Like Wendy Torrance, only more so, Marian Rolf (Karen Black) devotes herself to maintaining the house to the gradual neglect and exclusion of her family, while husband Ben (Oliver Reed) finds deep-seated resentment at his family responsibilities turning towards anger and violence. Aging Aunt Elizabeth (Bette Davis), who may be the likeliest person to understand the house’s sinister motives, has her mind gradually eaten away in a kind of induced dementia, while young David (Lee Mongomery, the rat’s friend in Ben) is the designated human sacrifice demanded by the house.

Although the movie could have used a bit more style, the strong cast do much to make up for Curtis’ limitations as a director. Karen Black was probably never better than here as a woman who becomes consumed by the fulfillment of her deepest material desires, giving up everything to become one with a property she never thought she could afford, while Bette Davis (despite apparently viewing the whole affair as trash) gives the movie some of its most emotional moments as a woman losing her bearings and facing her own mortality with confusion and fear. But perhaps best of all is Oliver Reed, keeping his force-of-nature persona under control as he does a far better job than Jack Nicholson in The Shining as a man confronting a darker and more dangerous side of himself than he’s ever been aware of.

The transfer is fine considering that Jacques Marquette’s photography is essentially just functional rather than particularly atmospheric. There are two commentaries (director Curtis, actor Black and co-writer William F. Nolan; and an informative account of the production by Richard Harland Smith), plus interviews with Lee Montgomery, writer Nolan, and actor Anthony James, who plays the sinister chauffeur in Ben’s creepy flashbacks to his mother’s funeral.

*

Two by John Grissmer

I don’t think I’d ever heard of John Grissmer before browsing Arrow’s catalogue for half-price Blu-rays a couple of months ago. They had two disks for sale – which turned out to be the only two features Grissmer had directed (he’d written and directed one other feature in the early ’70s, which I now have on order from Code Red). The first one to catch my eye was Blood Rage (1983, released in 1987), one of many ’80s slasher movies unearthed by Arrow in recent years. I added it to my order, then came across what looked like a very different kind of movie which also bore Grissmer’s name, Scalpel (1976), so while I was at it, I ordered that too.

I watched Blood Rage first and wasn’t terribly impressed although it had interesting elements. It follows the standard slasher formula – a prologue in which a child commits a horrific crime, followed by the body of the story (here set on Thanksgiving night) in which the now-grown child goes on a new rampage. The interesting twist here is that there are actually two kids, twins, and the one who commits a random axe murder at a drive-in frames his more timid brother. The brother is sent to a mental hospital while the more outgoing killer grows up to be a star high school athlete and popular kid.

On Thanksgiving Day, the brother who was framed, and who has recently emerged from a virtually catatonic state, escapes and returns to his hometown. The killer, hearing this news, loses control and goes on a killing spree, easily blaming his “crazy” brother for the mayhem. There’s some graphic gore, but as the story develops what’s most interesting is the warped relationship between the killer and his mother, which soon reveals some unhealthy incestuous undercurrents.

Louise Lasser (TV’s Mary Hartman) throws herself into the role with a degree of commitment which is genuinely creepy, while Mark Soper does a good job of delineating the two brothers as distinctly separate characters. But the movie is awkwardly paced and constantly feels uncertain of the tone it’s aiming for. The straightforward slasher narrative repeatedly seems to slip into parody, but it’s not clear that it’s meant to come across as comic, and the ending is creepy and chilling as even Mom becomes confused about which son is which …

Given the awkwardness of Blood Rage, I was pleasantly surprised by Scalpel, which is a much better crafted movie, more comfortable as a Southern Gothic, Hitchcock-inflected melodrama than the other film is in its more current genre. There are enough similarities in terms of narrative content to indicate Grissmer’s personal obsessions and interests. Once again there are “twins” played by a single actor, and here there’s a much more overt treatment of incest.

Robert Lansing is Dr. Reynolds, a prominent Georgia plastic surgeon with an unhealthy attachment to his daughter Heather (Judith Chapman). One night, after spying through a window and seeing her making out with her boyfriend, he kills the boy as he leaves the house – an act witnessed by his daughter who, instead of reporting him, runs away and disappears. Some time later, his father-in-law dies and leaves the family estate to the missing Heather, shutting Reynolds out (the old man’s dislike is entirely warranted as, in a flashback, we see him sitting by while his wife drowns in a lake).

Some time later still, Reynolds comes across a badly beaten woman in the street, her face all-but destroyed. She has no ID and minimal consciousness. He gets an idea, and carefully reconstructs her ruined face in the image of Heather. As she recovers, he pitches her the idea of standing in for his daughter long enough to claim and split the inheritance. For the most part, all the family and friends accept the switch – all except Uncle Bradley (Arlen Dean Snyder), whose suspicion pretty well dooms him.

Everything seems to be going well – although the sexual attraction between Reynolds and “Heather” is decidedly creepy given her resemblance to his daughter – until the day Heather returns. The back end of the film contains some unexpected twists, with Reynolds becoming increasingly unhinged as an odd bond develops between Heather and “Heather”.

This is a much more polished film than the later Blood Rage, nicely shot by Edward Lachman (his first 35mm project at the start of a notable career) and performed well by a talented cast. More certain in tone, it’s an effective addition to the genre of slightly rancid family melodramas set in the South.

Both disks feature strong transfers and multiple extras. Blood Rage has a commentary from Grissmer, plus interviews with producer/actor Marianne Kanter, stars Mark Soper and Louise Lasser, special make-up effects creator Ed French, and (briefly) Ted Raimi who makes a quick early appearance in the prologue. There’s also a featurette about the Florida locations. (I missed out on the original special edition, which included two alternate cuts of the movie – the original theatrical release, and a composite of that and the current cut, which is designated the home video version.)

Scalpel has a commentary from Richard Harland Smith and new interviews with Grissmer, Chapman and Lachman. Most interestingly, there are two very different encodings of the film based on the same restoration; the first, done by Arrow, treats the image conventionally, while the second, supervised by Lachman, reflects his much more stylized intentions which involved using various filters and colour manipulation to give the image a kind of stifling hothouse feel which emphasizes greens and yellows. Though I’ve seen some negative comments about Lachman’s choices on-line (particularly Nathaniel Thompson at Mondo Digital), I agree with Gary Tooze at DVDBeaver that the stylized image is preferable – Arrow’s naturalistic treatment looks much flatter and less atmospheric.

*

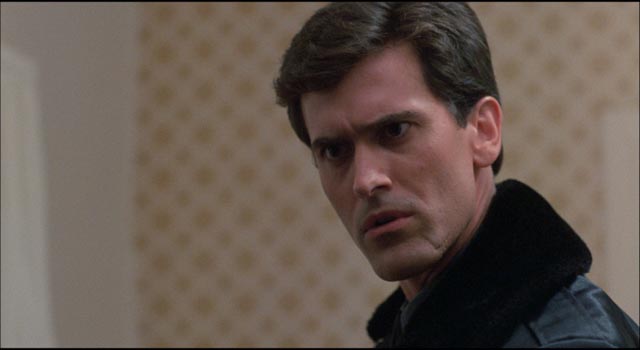

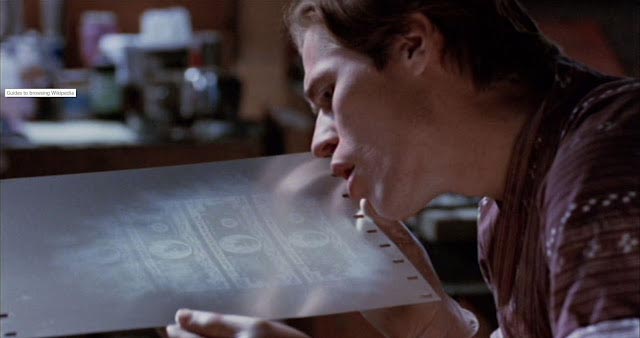

To Live and Die in L.A. (William Friedkin, 1985)

And speaking of stylized visuals, William Friedkin’s To Live and Die in L.A. (1985) looks much more dated today than The French Connection, made fourteen years earlier. The latter has that gritty documentary look, while the former has a slick, music video-like sheen, which gives Los Angeles an artificial atmosphere. Which is not to say that it isn’t one of Friedkin’s best films.

Carried over from the ’70s is a sour, cynical attitude towards the characters which ultimately makes it virtually impossible to distinguish between “good guys” and “bad guys”. Eric Masters (a young Willem Dafoe) is an artist who makes a living forging U.S. banknotes. He’s also a charming psychopath, who early in the film kills a federal agent snooping around his warehouse. That agent (just three days away from retirement in one of the film’s few glaring cliches) was the partner and mentor of Agent Richard Chance (William Petersen in his first starring role – and only second screen appearance); and naturally Chance is determined to bring Masters down, no matter what it takes. And it takes a whole lot of rule-breaking, which causes more and more stress for Chance’s new partner John Vukovich (John Pankow).

Chance’s obsession gradually transforms him into a figure as dangerous (and lawless) as Masters; he uses and hurts people to further his scheme, which is as likely to end in summary execution as arrest. He twists Vukovich’s arm into helping him hit what he thinks is a mob courier in order to get the money he needs to trap Masters into the sale of forged currency – but the plan goes very wrong, ending with the death of an FBI agent. By this point, the law no longer means anything to Chance; all that matters is revenge.

Friedkin tries to top The French Connection with a car chase on the L.A. freeway, and it’s an inventive and exciting sequence, but it lacks the earlier film’s visceral sense of danger. By the time of To Live and Die in L.A., Friedkin had honed his directing skills, but lost some of his risk-taking maverick quality. Added to the more conscious style is a score by Wang Chung, which serves to make the movie look even more like the upcoming work of Michael Mann (who would consolidate his position as one of the most stylish directors in Hollywood the following year with Manhunter [also starring William Petersen]) than recalling Friedkin’s own earlier work.

As usual, Arrow’s video presentation is very good and the disk has numerous extras, beginning with a commentary from Friedkin, and including interviews with actors Petersen, Dwier Brown and Debra Feuer. There are additional interviews with Wang Chung and stunt co-ordinator Buddy Joe Hooker. There’s also an archival making-of featurette, a deleted scene (from a degraded video source), and an alternate “happy” ending which Friedkin shot at the insistence of the distributors – so ridiculous that it could never be used.

*

Shock Treatment (Jim Sharman, 1981)

I was never a committed member of the Rocky Horror cult, though I saw the movie a couple of times in the theatre (once on its original release, later at a midnight screening at the Epic on Main Street here in Winnipeg where the crowd performed all the audience rituals), and a couple more times on DVD. There are things to enjoy – I like Richard O’Brien’s score (and used to be able to sing along with all the songs) and the movie’s easy-going pan-sexuality. But as a movie, it always seemed kind of clunky, only partially liberated from its stage origins.

Ironically the “sequel” was mostly hated by the cult and dismissed or ignored by almost everyone else – yet I loved it from the first time I saw it. Again written by O’Brien and directed by Jim Sharman, Shock Treatment (1981) was conceived as a film, designed around the musical numbers, with a critique of visual culture (film and more specifically television) embedded in its form and narrative. Long before “reality television”, the film breaks down the separation between performer and audience, incorporating the audience into the show; it all takes place in a studio where the life of small town Denton, Ohio, exists only as a commercial enterprise.

The disintegrating marriage of Brad and Janet (here Jessica Harper and Cliff DeYoung) becomes the material for a new show – therapy as game show, or game show as therapy – with Janet promoted to hot new star while Brad is locked up and drugged, not by doctors but rather actors who play doctors on TV. The couple have been separated deliberately on the whim of uber-sponsor Farley Flavors who has designs on Janet, not least out of bitter rivalry towards Brad (turns out they were twins separated at birth – which makes three out of seven movies which feature actors in dual roles).

When Shock Treatment first came out, it was a piece of social science fiction disguised as a musical comedy; seen today, its depiction of a world in which triumphant capitalism has transformed people into the very commodities they consume seems all too real. Brad and Janet’s psychodrama plays out on-set and behind the scenes through a series of sketches and upbeat musical numbers which show the commodification of people and their emotional lives for the profit of all-encompassing, corrupt corporations. It’s a darker, more sinister movie than Rocky Horror (I recall one critic’s comment that it’s something like a musical comedy version of Last Year at Marienbad), and personally I think it has a better (if perhaps less catchy) score.

Arrow’s Blu-ray has a lushly colourful transfer, all the extras from the old 20th Century Fox DVD, plus a new commentary from actors Patricia Quinn and Nell Campbell, and a conversation between Quinn and critic Mark Kermode. One of my favourite musicals, and definitely well-served by Arrow.

Comments

I haven’t seen all of those films, who’s got the time. I know what you mean by never catching up. I hit the used DVD stores in the area last weekend. Half Price Books was having a 20% off everything you buy sale and they have a good DVD and Blu-ray section. Plus their clearance area is often a good source of iffy titles I might want to see but didn’t want to pay full price. I was bringing home 15-20 movies from each of the 5 stores I visited. Then I had a big Hamilton Books order come in and that yielded 31 more movies and some TV. I’ve already see over 440 movies this year, that’s just the ones I hadn’t seen before. I only brought home 4 movies this week, maybe there’s hope.

One film I really liked earlier in the week was House Of Bamboo with Robert Ryan. That guy was so good.

I have a friend who owns two (or is it three?) movies on disk – Lawrence of Arabia and Michael Mann’s Last of the Mohicans. I sometimes envy him!

At the height of my disk addiction, back in the ’00s, I was spending a couple of hundred or more a week, going home with stacks of movies. Some of them, I still haven’t got around to watching. And yet, I can’t stop even if I have slowed down.

I’ll watch anything with Robert Ryan in it … one of my all-time favourite actors.

I watched Jim Sharman’s The Night The Prowler the other day and didn’t care for it that much. It was kind of dull and not that interesting, at least to me. I got the Code Red 2 movie DVD, it’s oddly pair with Devil Woman. That wasn’t to good either. I’ve seen several of Code Red’s recent Blu-rays and they sure have some poor movies in their catalog.

I did pick up the 30th Anniversary Blu-ray of Rocky Horror Picture Show but haven’t gotten to it yet. I had the DVD but haven’t watched it since after it was new. I liked that movie but I didn’t much care for seeing it with all the hoopla in the theater.

I did like Shock Treatment when I saw it in the theater when it was new. Not quite as good as RHPS but entertaining enough. I have the DVD but haven’t seen that in many years either. I should have a double bill.

I’ve never seen Sharman’s other three features … guess I should check them out.

Well, you’ve convinced me. I’m not going to buy any more movies until I watch all the DVDs and Blu-Rays I own, as well as all the digital movies I’ve purchased on iTunes. That should keep me occupied for a couple of months.

Only three months? If I stopped buying today, it would still take me a year or two to get through the unwatched disks!

FYI, I believe the friend of whom you speak has expanded his collection to include the first three Alien movies.

I’m surprised … I didn’t know he was a fan, except maybe for the first Alien.