A Terence Stamp double-bill

Terence Stamp has always seemed to stand slightly apart from such contemporaries as Albert Finney and Alan Bates. Unlike them, both prone to be large and extroverted and occasionally somewhat bombastic, Stamp seems more contained, an actor with quiet surfaces and an inner intensity. His choices of role have been nothing if not eclectic. He began his screen career at twenty-four as the title character in Peter Ustinov’s film of Herman Melville’s Billy Budd (1962), immediately following that with a supporting role opposite Laurence Olivier in Peter Glenville’s adaptation of James Barlow’s novel Term of Trial (also 1962); then came the lead in William Wyler’s film of John Fowles’ The Collector (1965), Monica Vitti’s sidekick in Joseph Losey’s campy Modesty Blaise (1966), the darkly romantic Sergeant Troy in John Schlesinger’s glossy version of Thomas Hardy’s Far From the Madding Crowd and the petty criminal Dave in Ken Loach’s gritty debut feature Poor Cow (both 1967). In 1968, he starred in Silvio Narizzano’s misbegotten western Blue, Federico Fellini’s Toby Dammit (the third and best segment of the Poe omnibus Spirits of the Dead) and Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema.

Throughout the 1970s, he made odd, obscure choices – mostly shot in various European countries, with a brief excursion to big-budget Hollywood to play General Zod in Superman I and II. He made a “comeback” of sorts in 1984 as ex-gangster Willie Parker tracked down by a pair of hitmen (John Hurt and Tim Roth) in Stephen Frears’ The Hit, but in the ensuing three-and-a-half decades, Stamp has mostly been busy as a distinctive supporting presence in dozens of features and television shows. His biggest role, and one of his finest, during this period was in Steven Soderbergh’s The Limey (1999). Notably, Soderbergh drew on the actor’s history, using “flashbacks” drawn from Loach’s Poor Cow to gave weight to the character of Wilson, a brutal but weary criminal who travels to Los Angeles to track down the man responsible for his daughter’s death.

What made the younger Terence Stamp both distinctive and perhaps not suitable for mainstream movie stardom is apparent in two early films recently released on Blu-ray by Indicator – his first brush with Hollywood in The Collector and, more enigmatically, the lead in a low budget Amicus production called The Mind of Mr. Soames (1970). Both films showcase the actor’s unsettling interiority, disturbing depths beneath a seemingly placid surface. Despite their obvious differences in quality, each movie affords Stamp an opportunity to dominate the production.

The Collector (William Wyler, 1965)

John Fowles experimented with form and genre throughout his career. His first published novel, The Collector (1963), used the psychological thriller as a hook on which to hang arguments about class and gender in contemporary England. A working class man who wins some money buys a remote country house and acts out his fantasy by kidnapping a middle class art student. Keeping her prisoner in a cellar, he believes that she will fall in love with him once she gets to know him … but of course things don’t work out as planned.

Fowles was not happy with the film version produced by Columbia in 1965. The script by Stanley Mann and John Kohn concentrated on the genre elements and simplified the philosophical arguments and director William Wyler, a venerable old Hollywood hand nearing the end of a very long career, gave it the kind of studio gloss that nudged it towards theatricality when it would have benefited from a starker, more realistic approach. Rather than playing with genre as the book does, the movie wholeheartedly invests in the generic elements it reiterates.

Essentially a two-character chamber drama, with exteriors shot in England and interiors shot on studio sound stages in the United States, Wyler’s The Collector is a tense post-Psycho thriller which relies almost entirely on its two stars to give it more depth than the contrived narrative would otherwise possess. But most importantly, Wyler lacks Hitchcock’s willingness – eagerness – to dig curiously into the darker recesses of the characters’ emotions and desires. Despite the strength of the performances, The Collector remains rather polite and tasteful.

Which is not to say that I dislike the movie; only that in other hands it might have been in a class with Vertigo, Psycho and Peeping Tom, rather than belonging to a more generic women-in-peril tradition – along with movies like Blake Edwards’ Experiment In Terror (1962), Terence Young’s Wait Until Dark (1967) and Richard Fleischer’s See No Evil (1971).

Samantha Eggar is very good as the put-upon Miranda Grey who has to carefully navigate a situation in which she is completely at the mercy of someone she has a hard time gauging, someone who is a direct threat to her own survival even though he presents himself as mild and considerate. Her situation and her likeability earn audience sympathy by default; yet Terence Stamp also manages to seem sympathetic even as his Freddie Clegg becomes creepier and more menacing.

From our perspective, what seems most interesting about the film now is not Fowles’ intellectual class struggle, but rather its presentation of gender conflict. Clegg is a so-called incel avant la lettre, an insecure man with little personal appeal who has been the butt of jokes all his life, who has always felt that what he desires is unfairly out of reach. But when he wins the football pools and suddenly finds himself modestly independently wealthy, he sees an opportunity to bend the world to his own desire.

He is resentful because his lowly position has rendered him virtually invisible (except as an object of his co-workers’ ridicule), someone an attractive woman would never even notice. But he believes that all he needs to do is get Miranda alone for her to see him and, inevitably, fall in love with him. He’s convinced that his own desire for her (nursed over time by watching her at a distance in their shared home town) means that he is owed her love; how can his desire not be requited? He deserves her and he can’t understand why she resists … after all, he is so solicitous of her needs and comfort in the prison he has made for her in the cellar.

As a woman imprisoned, Miranda has to navigate their encounters carefully, interpreting his moods and intentions, playing a role which to a degree conforms to his fantasy even while trying to assert her own sense of self. Rather than a metaphor for class struggle, the movie is a chilling depiction of the inherently abusive tendencies in unequal gender relations, the portrait of a smart, confident, independent woman who nonetheless must do what she can to accommodate the desires of an unpredictable man, always fearful of antagonizing him even as she searches for ways to escape him. Because of the long history of gender inequality, despite her inherent strengths and his weak, confused immaturity, he holds all the power in a “relationship” over which she has no control.

Stamp manages to convey a great deal of Freddie’s confusion and resentment through body language and facial expressions, while his dialogue much of the time exposes him as a petulant child who simply can’t understand why he isn’t getting what he wants. In its way, this stolid dumbness is as chilling as Anthony Perkins’ jittery nervous energy in Psycho, and to some degree more realistic.

*

The Mind of Mr. Soames (Alan Cooke, 1970)

American writer-producers Max J. Rosenberg and Milton Subotsky established Amicus Productions in England in the early 1960s to cash in on the genre filmmaking success of Hammer Films and American International Pictures. Like those models, the company worked with limited budgets and exploitative material to attract a younger audience looking for cheap thrills. Its movies drew on AIP’s Poe series and Hammer’s psycho horrors for inspiration, but the company became best-known for its series of horror anthologies, beginning with Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors in 1965 and ending with From Beyond the Grave in 1974. There were also stand-alone horrors, sci-fi, straight thrillers, and finally several Edgar Rice Burroughs adaptations, but many of these suffered from inadequate budgets (though I have a certain fondness for the cheesy Burroughs movies despite their often shoddy effects).

My favourite Amicus movie, and one which for a long time got very little love from anyone else (it’s slowly gained a certain cult status), is Gordon Hessler’s deranged Scream and Scream Again (1970), an unpredictable mix of multiple genres guaranteed to confuse first-time viewers.

Potentially more interesting, but approached with less imagination, is Alan Cooke’s The Mind of Mr. Soames (also 1970). Adapted by John Hale (Oscar nominee and Golden Globe winner for Charles Jarrott’s Anne of a Thousand Days [1969]) and Edward Simpson from a novel by minor British science fiction writer Charles Eric Maine (real name David McIlwain, whose work was the basis of three features in the 1950s[1]), production of the film may have been inspired by the success of Ralph Nelson’s Charly two years earlier. Charly was based on a short story by Daniel Keyes first published in 1959 and expanded to novel length in 1966; Maine’s novel was written in 1961, so perhaps he had encountered Keyes’ short story. But regardless of any literary connection, Amicus may well have decided to make the movie because of the box office and awards success of Nelson’s film.

I haven’t read Maine’s novel (though I did own a copy back in the ’70s), so I don’t know whether the adaptation’s weaknesses are inherent in the source, but the movie begins with an intriguing idea the implications of which it can’t quite follow through to a satisfying conclusion. John Soames was born in a coma and has been kept alive at an institution run by Dr. Maitland (Nigel Davenport) for some thirty years. Now, thanks to neurosurgeon Dr. Bergen (Robert Vaughan), there’s the possibility of waking John with an operation to activate a “sleeping” part of his brain.

For Bergen, this is a medical problem to be solved; for Maitland, it’s an opportunity to achieve accolades and to try out his theories of learning. A publicity seeker, he has invited a television documentary team to come in and make a series about Soames’ progress, beginning with cameras at the operation itself. This sets up an on-going conflict between the two doctors – one is concerned for the patient, the other views him as an experimental subject with no right to an autonomous existence. Davenport plays Maitland as an arrogant jerk, which makes Vaughan seem warmer and more empathetic than usual (he was an actor whose manner was most often cool and detached, with an edge of self-aware humour).

Although the early sections of the movie set up a prescient critique of the pervasive intrusion of media into our lives, with the possibility of “real life” becoming a media construction, this thread disappears part way through, only to reemerge as a deus ex machina in the final sequence. After the initial stages of John’s awakening and Maitland’s rigid training regime, the story focuses on the tug-of-war between the two doctors over the child-man, with Bergen believing that he needs opportunities to experience and learn from his environment, while Maitland believes he’s an empty vessel to be filled in accordance with a tightly planned schedule. Not surprisingly John chafes at his confinement and rebels against this training.

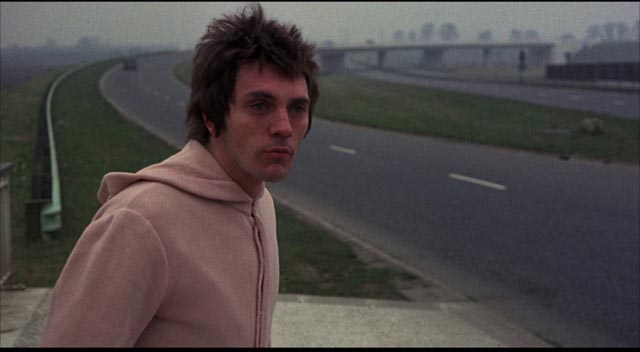

After being introduced to the outside world by Bergen – who one morning lets him out into the institute’s grounds – his imprisonment becomes intolerable and he breaks out (seriously injuring one of his attendants in the process). Unformed and completely inexperienced in social interactions, John wanders around, his innocence causing problems (he steals a sandwich from a pub because he’s hungry; he scares a schoolgirl in a train compartment) and is pursued by the police for “attempted murder” (due to the assault on the attendant during his escape).

Maitland’s wrong-headed training regime has completely failed to equip him for being in the world; although it isn’t overtly stated, he becomes an analogue for Karloff’s monster in the original Frankenstein – a creation of science misunderstood and feared by those he encounters, his own lack of understanding perceived as malevolence. Cornered at last (in a barn on a rainy night, rather than in a windmill), Maitland blusters and shouts at him, while Bergen tries to reason calmly. It’s Bergen’s empathy which works … until the TV crew ruin things in their desire to get a big finish for their documentary. But for all the chaos outside the barn, the movie ends rather anticlimactically.

Director Alan Cooke, a veteran of British television whose only full-length theatrical feature this was, handles things efficiently but without much style. But the performances are quite good, with Davenport and Vaughan giving a bit of life to their schematic conflict. Best of all, though, is Terence Stamp as John Soames; he once again conveys a great deal of the character’s interior life through body language and expressions – even more so here because his use of language is much more limited. As a newborn baby in a man’s body, he is constantly testing the world around him and most particularly pushing back against the overly controlling parent Maitland. Stamp is adept at conveying the subtle underlying humour in much of this testing, gauging how far he can go in provoking Maitland and enjoying the reactions he gets when he pushes a little too hard.

In The Collector, Freddie’s lack of self-awareness turns out to be lethal; in The Mind of Mr. Soames, John’s innocence is only an inadvertent risk for others – his inexperience of the world is more dangerous to himself. Stamp plays the two sides of this coin with equal deftness, gaining audience sympathy for both characters even when doing harm.

*

Indicator’s Blu-rays do justice to both films, with The Collector not surprisingly getting a more substantial treatment. The 2K transfer has a good film-like look, with strong contrast. The Soames transfer reflects that film’s lower budget with occasionally weaker visuals, but a pleasing representation of the film grain and strong though muted colours.

The Collector includes a pair of lengthy audio interviews – one with Wyler from 1981, the other with Stamp from 1989 – plus a select-scene commentary from film historian Neil Sinyard. In a new interview, Stamp talks about his early career and getting the role even though he felt he was unsuitable for the part of Clegg. There’s also a new interview with Eggar, plus an odd contemporary promo piece in which she was presented as a major new star. A brief featurette looks at the film’s locations, and critic Richard Combs offers an appreciation of the film. A substantial booklet has essays on the film and its source, plus excerpts from contemporary reviews.

The Mind of Mr. Soames comes with another new interview with Stamp, in which he talks about his early career and the gaps in his work in the ’70s – but unfortunately he doesn’t have a word to say about Soames. There’s a very brief featurette in which several people involved in the production offer reminiscences. Most substantial is a commentary track with British genre experts Kevin Lyons and Jonathan Rigby talking about the film and its place in British science fiction cinema. The booklet contains a new essay on the film, archival interviews with the three stars, and profiles of cinematographer Billy Williams and original author Maine, plus the usual excerpts from contemporary reviews.

_______________________________________________________________

(1.) Terence Fisher’s dull Hammer=produced Spaceways (1953); Ken Hughes’ The Atomic Man (1955); and Montgomery Tully’s The Electronic Monster (1958). (return)

Comments

I just watched the copy of The Collector I had a few days ago. It came from cable and I was wondering if I wanted to upgrade to a DVD. After watching it again I think I don’t need to see it anymore.

I was happy to pick up the Criterion DVD of The Lady Vanishes today. I’d seen it a couple of times before but the DVDr I had was recorded off of TCM and it’s kind of fuzzy. They had pretty low rez video on cable 10 years ago. The new DVD is much nicer, there’s some nice extras, and it was only 12 smackaroonies, plus tax, from a local used DVD store. I enjoyed the commentary and now I’m just getting to the end of Crook’s Tour. I’ll listen to the other extras next.

After watching The Lady Vanishes I decided to upgrade my copy of Night Train To Munich to the Criterion version. Same reason, poor copy off of TCM. I like some of the films that Launder and Gilliat did. I really like their 1946 film Green For Danger with Alastair Sim.

I must be on a Hitchcock kick, I just ordered a 15 Blu-ray set of his films two days ago, 17 discs for 61 bucks. I didn’t have all of them on DVD so that’s a bonus.

I was really disappointed by Crook’s Tour when I watched it years ago as an extra on Criterion’s Lady Vanishes DVD. Charters and Caldicott just couldn’t carry a whole movie by themselves – it just went to show how good Launder & Gilliat and Hitchcock were. (It was directed by John Baxter the same year he made the vastly superior Love on the Dole.) As for Night Train to Munich, despite the Launder & Gilliat script, it lacks Hitchcock’s panache; Carol Reed made some great movies, but here he just didn’t seem right for the mix of adventure, serious drama, romance and comedy. Totally agree with you about Green for Danger, though; it’s a wonderful film that should be better known.

I almost bought the Hitchcock Blu-ray set the other day. A local store had it on sale for about 70 bucks Canadian. But I have five of the movies on BD already and there are still apparently issues with some of the transfers which Universal hasn’t bothered to fix as they re-released the set a couple of times. I’m not terribly picky, but I do get annoyed by major companies that don’t seem to care about the quality of their releases.