Andrei Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev (1966):

Criterion Blu-ray review

I was lucky enough to see all but one of Andrei Tarkovsky’s features for the first time in a theatre – from Solaris in London in 1972, to Stalker and Andrei Rublev in Hong Kong during the winter of 1980-81, to Mirror and Nostalghia in London in 1984 and The Sacrifice in Winnipeg in 1986. The exception is Ivan’s Childhood, which I have only seen on home video (the first time on VHS!). I’ve seen all of these films multiple times, both in the theatre and on home video, and his body of work stands apart for me in its own special place; these are films which I experience in ways quite different from almost all others.

Tarkovsky’s work has an intense physical presence; in watching them we seem to experience the sheer materiality of the world – they are primal and elemental; we feel the heat of fire, the cold clinging of mud, the mysterious touch of wind which can be seen only through its effect on grass, trees, objects which it moves, and perhaps most of all the restless motion of water which falls and flows throughout his work. But there is a powerful counterpoint to the sense of physical presence in his films, a palpable energy which suffuses this materiality with a spiritual force. While this is often informed by Christian symbolism, it seems to go deeper and reaches back into something more ancient, more primal. In Tarkovsky’s work, the material world is animated by this metaphysical energy.

Although I’ve watched his films many times, it is still a mystery to me how he achieves this. He is endlessly observant of the physical world, of plants and animals and objects and human faces and bodies; and his use of a moving camera is crucial. He has a way of choreographing the actors and the camera so that in every shot we find ourselves exploring a space which extends in every direction beyond the frame. As characters interact with one another in constant, restless movement, the camera moves independently of them so that figures keep disappearing and reappearing in unexpected parts of the image. The camera isn’t simply a neutral recording device; rather it’s an intelligent presence as alive as the people it encounters as it travels on its own journey.

Each of his films immerses me in the sheer tactile beauty of the worlds he creates; and yet he can also be a very intimidating figure. He took his art so deeply seriously that throughout his career many accused him of being pretentious and humourless. He refused to compromise his aesthetic principles – even going so far as to say that any filmmaker who stooped to take a job merely for the sake of working had irredeemably corrupted himself as an artist. In ways few other filmmakers have ever done, Tarkovsky demands a commitment from his audience; he is not there merely to divert or entertain – he insists that you enter his world fully on his terms.

This is the source of a paradox at the heart of his career, a paradox which relates to his position as a filmmaker in Soviet Russia. Filmmaking, like so much else in that country, was a state-controlled enterprise. Filmmakers were expected to advance the purposes of the state, to manifest in their work the socialist realism which confirmed the historical inevitability of the political and economic progress stemming from the Revolution. Even Tarkovsky, like so many of his generation, began his career with a film belonging to the revered genre of Great Patriotic War films. And yet even here, he already showed his divergence from his contemporaries – yes, Ivan’s Childhood (1962) is about the sacrifices made in the monumental fight against fascism, but the film distances itself from such masterworks as Mikhail Kalatozov’s The Cranes Are Flying (1957) and Grigoriy Chukhray’s Ballad of a Soldier (1959) by concerning itself with that numinous energy which underlies and extends beyond the immediate experience of the characters. As tragic as the events of the war are for Ivan and his companions, the film suggests that these personal experiences occur within a much larger, more timeless context where specific politics are only tangentially relevant to life and death.

Ivan’s Childhood nonetheless convinced the Soviet filmmaking bureaucracy of Tarkovsky’s value and, remarkably, for his second feature he was given virtually unlimited resources. It seems extraordinary that from the small-scale and intensely personal Ivan, he should have gone on to make one of the biggest – and arguably the greatest and most authentic – historical epics in cinema history. In Andrei Rublev (1966), he creates a sweeping evocation of the chaos of Medieval Russia, a world of brutal violence and deadly social inequality, moving freely between intense interactions among small groups and expansive panoramas with landscapes full of crowds and armies in battle.

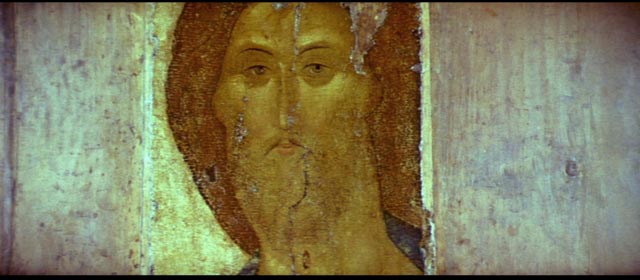

Set during the early 15th Century, at the time of the Tatar invasions, on its surface Andrei Rublev depicts the early stages of the formation of the Russian nation, and this no doubt was what gained the bureaucrats’ approval. But Tarkovsky and co-writer Andrei Konchalovsky hang the film’s disparate episodes on the character of Andrei Rublev, the greatest of Russia’s icon painters, a paragon of deeply committed religious art. As little is known of the real Andrei Rublev, the filmmakers felt free to invent a range of experiences for their character, providing a panoramic view of this society in turmoil. The central theme of the film is Andrei’s struggle to reconcile the horrors (and occasional beauties) he witnesses with the idea of God. We never actually see him painting, but by the end his doubts have been resolved and the black-and-white film bursts into colour for an epilogue in which the camera explores in close-up detail the vibrant icons he eventually produced.

The film’s release was delayed and the censors demanded some changes – there was too much violence, too much nudity. But more importantly, Tarkovsky had suffused the film with his spiritual concerns, rather than presenting a materialist view of history. This set up the conflicts which plagued his next three films – Solaris (1971), Mirror (1974) and Stalker (1979). And yet despite these difficulties (he was repeatedly attacked for being too obscure, too personal), these films were nonetheless made possible by the state production apparatus. But in the end, Tarkovsky’s refusal to bend from his own artistic purposes resulted in the collapse of what would have been his sixth feature, another historical film called The First Day. It was after this that he went into exile, making his final two films in Italy (Nostalghia [1983]) and Sweden (The Sacrifice [1986]). While the first of these took as its subject the artist’s exile and the toll taken by being cut off from one’s own cultural roots, the second (perhaps the weakest of his films, despite many superb sequences) seemed to drift in a generalized world too obviously drawing elements from Ingmar Bergman’s work.

One of the most remarkable things about Andrei Rublev, beyond the massive scale of the production which Tarkovsky seems to have managed with ease, is how he gives it a sense of intimacy despite that scale. Even though Andrei himself drifts in and out of events, sometimes disappearing completely for lengthy stretches, we never doubt that we are seeing this world through his eyes. With him, we strive to make sense of the chaos, to seek an underlying meaning which might stave off overwhelming despair.

Structured in eight chapters which are bracketed by a prologue and epilogue, the episodic narrative provides space for observation and contemplation while leading Andrei through doubt towards a final epiphany. The prologue (the most overtly fantastical invention in the film) establishes a conflict between creativity and the restraints of dogma and convention; a small group of men are preparing a ramshackle hot-air balloon beside an abandoned church as villagers hurry towards them in boats on the nearby river, determined to stop this blasphemous affront to the natural order. The proto-aeronaut manages to get aloft and the camera sweeps above the fighting crowd below and drifts out over the landscape with an exhilarating sense of freedom … before the balloon ruptures and crashes to the riverbank, apparently killing the pilot. Here, human ingenuity strains to push against the physical limitations of the world, towards modernity, while the fearful mob attempts to hold the explorer back with violence.

There is no direct connection between this event and what follows, and yet it establishes the idea of the human potential to expand and break free from physical and social constraints. This tension permeates the episodes which follow, each of which deals in one way or another with the social and political forces which try endlessly to hold back and stifle expressions of creativity and freedom. Beginning with small, local events – Andrei (Anatoliy Solonitsyn), seeking shelter from the rain, sees a peasant who mocks the social order taken away and imprisoned; Andrei’s companion Kirill (Ivan Lapikov), jealous of Andrei’s superior talent, tries to become the protege of Theophanes the Greek (Nikolay Sergeev) only to have the master offer the position to Andrei; Andrei witnesses a moonlit pagan ritual by a river, naked men and women expressing a free physical joy, who the next morning are rounded up by men on horseback; a wintry reenactment of Christ’s Passion – all leading eventually to the destruction of the city of Vladimir by the Tatars in league with the ruling prince’s embittered younger brother.

The attack is brutal and relentless, sweeping aerial views of the invading army interwoven with brutal moments of individual violence. Andrei witnesses the slaughter of citizens who have taken refuge in the cathedral and himself kills a soldier in order to rescue a mute young woman. In response to the horrors he has seen, he takes a vow of silence and retreats to his original monastery with the woman (one of the holy fools who appear throughout Tarkovsky’s work, figures touched by madness which perhaps connects them more intimately with the divine – a thematic thread which reaches its richest expression in the Stalker).

When the Tatars arrive at the monastery, Andrei attempts to protect the woman from them, but she chooses to go with them, and Andrei, seemingly powerless to affect events or protect the innocent, wanders out into the world again. He becomes a secondary character, only occasionally glimpsed, in the long final section which focuses on Boriska (Nikolay Burlyaev, Ivan in Tarkovsky’s debut feature), a boy discovered alone in a village wiped out by plague. He is found by men sent by their lord to find a renowned bellmaker. Boriska insists that his father passed on the secret of casting a bell before he died and the men take him back with them. A mixture of immature insecurity and arrogance, the boy asserts himself over the craftsmen whose job it is to make a huge new bell for a cathedral; he antagonizes them with his demands as he searches for the perfect clay for casting and tells the prince’s men that he needs much more silver for the smelting.

Tarkovsky’s mastery of physical detail provides a vivid depiction of the process of bellmaking, with Andrei occasionally glimpsed on the periphery. Once the bell has been raised from its clay fire pit and the prince and his European guests have ridden out of the city followed by the population who have come to witness the first ringing, its deep clear tones spreading across the landscape, Andrei learns the secret Boriska has been harbouring. Perceiving an unseen hand working in the boy’s fate, Andrei can finally overcome his doubts and begin to paint again, producing the masterpieces for which he is known … and which Tarkovsky’s camera now lingers over.

In Andrei Rublev, Tarkovsky achieved his first full expression of the integral duality of the world, the material in uneasy balance with the spiritual, a theme he explored with increasing subtlety in his subsequent work. In this epic, he created a Medieval world so full of life and rich in detail that it has few if any equals.

*

The disk

Criterion’s two-disk Blu-ray edition presents Tarkovsky’s preferred 183-minute cut on disk one (ironically, this was the version which resulted from the censors’ demands for changes after the first screening) and the original 206-minute The Passion According to Andrei on the second disk. (Tarkovsky himself did the cutting and later said that the film was much improved by the tighter, more focused editing.) The shorter version, from a 35mm internegative, looks quite spectacular, with a rich film-like texture, strong contrast, and a lot of fine detail. The longer version is much weaker, scanned from a rather battered print (supplied by Martin Scorsese) with scratches and dirt apparent throughout, weaker contrast, and burned-in subtitles.

There are differences in the audio tracks as well, with the first disk much stronger, with clear dialogue and natural ambiences. The music by Vyacheslav Ovchinnikov is well supported. The track on the longer version is somewhat murkier, having been drawn directly from the print.

The supplements

The set includes a substantial collection of extras (all on the first disk for some reason).

Carried over from Criterion’s 1998 DVD edition is a select-scene commentary by film scholar Vlada Petric (49:44).

The Three Andreis (18:51) is a documentary about the writing of the script, made by Dina Musatova in 1966.

On the Set of “Andrei Rublev” (5:20) is silent archival footage of Tarkovsky directing the film.

Tarkovsky’s “Andrei Rublev”: A Journey (29:12) is a 2018 documentary by Louise Milne and Sean Martin about the making of the film, which features interviews with a number of people involved in the production.

Inventing “Andrei Rublev” (12:58) is a new video essay by filmmaker Daniel Raim about Tarkovsky’s creative process.

In an interview (37:00) film scholar Robert Bird discusses the relationship between the film and the historical Andrei Rublev.

Finally, Criterion include Tarkovsky’s thesis film The Steamroller and the Violin (1961, 45:26).

The booklet includes some remarks about the project by Tarkovsky published in 1962 and reprints J. Hoberman’s essay from the 1998 DVD.

*

With this comprehensive release joining Criterion’s previous editions of Solaris, Stalker and Ivan’s Childhood, I can only hope that a Blu-ray of Mirror will appear in the near future.

Comments