Random viewing: a grab-bag

One of the great benefits of digital technology has been the recovery and restoration of movies from the first wave of 3-D – mostly 1953-54, with a few stragglers from the later ’50s and early ’60s. The precision of digital imagery means that many of these films actually look better now than they ever did on theatre screens when they were dependent on the mechanical technology which was prone to headache-inducing misalignment.

One of the drawbacks is that viewing these restorations is largely dependent on 3-D TVs and active headsets (which themselves may trigger headaches if you over-indulge). This means, for me, that I can only see these movies in 3-D when I visit my friend Steve – which means less than full attention because we tend to drink and chat a lot as we watch.

The Bubble (Arch Oboler, 1966)

Most recently we watched a couple of later productions, both notable for their own reasons. The Bubble (1966) was written and directed by Arch Oboler, who had launched the original 3-D boom with Bwana Devil in 1952. Innovating once again, Oboler shot the movie in Space-Vision, a single strip technique which had the right and left eye images above and below each other rather than on two separate film strips. The big advantage here was that a single projector obviated the risk of misalignment and sync problems.

The biggest drawback in this instance was the fact that Oboler was a rather dull filmmaker. With a lengthy background as a successful and influential radio writer-producer, best-known for his work on Lights Out during the 1930s and ’40s, Oboler was prone to talky scripts rather than visual style. This makes even his best work (like the post-nuclear Five [1951]) a bit of a slog. The Bubble is a Twilight Zone-ish sci-fi story about a young couple whose plane is forced down in a small town which seems to be under a strange curse. People are suspicious and cagey and, more disturbingly, seem to be prone to repeat words and actions as if trapped in a loop.

The couple are unable to escape because the town turns out to be surrounded by a kind of force field. It seems that some alien force has enclosed it like a zoo exhibit. (Hmm, wait a minute … small town, alien force field, inhabitants cracking under stress – I wonder if Stephen King was conscious of remaking this in Under the Dome?) But while the narrative plods along, the 3-D photography creates an impressive sense of space, with even interiors having remarkable depth. Of course, the fact that the shape of a pillow on a hospital bed is enough to distract you from the scene being played out in the room is not a good sign with regard to the drama. Steve and I weren’t engaged by the story, but we were continually expressing awe at the 3-D effects.

The Mask (Julian Roffman, 1961)

A much better film is Julian Roffman’s The Mask (1961), Canada’s first ever horror feature. While best-known for its hallucinatory 3-D montage sequences (the work of famed experimental filmmaker Slavko Vorkapich), the film is a pretty good psychological horror movie. After one of his patients commits suicide, psychiatrist Dr. Allan Barnes receives a package containing an ancient tribal mask which, when put on, plunges the wearer into an alternate realm of nightmarish imagery, monsters and human sacrifices. Repeated use weakens the user’s connection to reality and brings out the darker aspects of personality, unleashing latent violent impulses.

The 3-D here is limited to the nightmare sequences, instilling additional impact in imagery which suggests something ancient and mythic – journeys through an underworld reminiscent of Greek mythology. The mask itself is a striking object with piercing eyes staring out of a mosaic skull.

The Mask is a well-constructed horror thriller, and the 3-D sequences are dense and vivid. Strangely, it was only the second of two features directed by Roffman, a former National Film Board director who made military training films during the Second World War. (His first feature, The Bloody Brood [1959], was a nihilistic story of Beatniks and drug dealers, which was the second feature for Peter Falk.)

Both films were restored by the 3-D Film Archive and released on disk by Kino Lorber. While The Bubble includes minimal extras (a couple of text supplements, an alternate opening and restoration demonstration), The Mask has more substantial supplements: a commentary by film historian Jason Pichonsky; a short documentary on Roffman; 3-D sequences encoded for anaglyph viewing; and several of Slavko Vorkapich’s short films and montage sequences. But most importantly, of course, both disks provide virtually pristine 3-D encodings.

*

CGI excess

Three more recent 3-D movies which I’ve only seen in 2-D lack the simpler charms of these older films. Like so many contemporary productions, they are bloated, over-stuffed with flashy visual techniques and largely uninvolving on a narrative level. While spectacle has always been an important element of cinema, the balance has shifted in recent decades to a point where it too often seems to be the only reason for big-budget movies to exist.

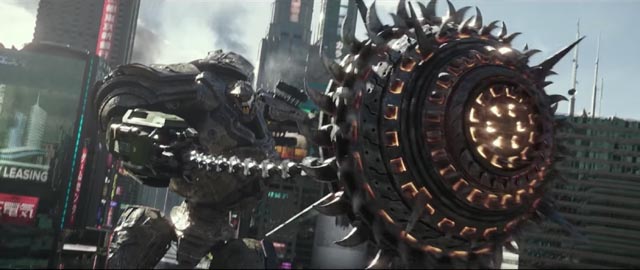

In the original Pacific Rim, Guillermo Del Toro put visual spectacle at the service of an avowedly adolescent love of fantasy, evoking a fourteen-year-old’s sense of wonder at the sight of giant monsters and robots and small human heroes fighting to save the world from destruction. Released five years after Del Toro’s movie, Steven DeKnight’s Pacific Rim: Uprising (2018) lacks all of the original’s charm and the fine attention to detail which gave Del Toro’s work a textural density which grounded the fantasy. The new movie is big and noisy and ultimately as disposable as the Transformers series.

More ambitious is Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther (2018), though beyond its sociological importance as a big-budget spectacle centred on Black characters, it is ultimately as insubstantial as all superhero movies. It’s obvious why audiences embraced its assertion of a scientifically and socially advanced African civilization (particularly in the face of waves of renewed racism in America under Trump), but the very fact that this alternative is cast as a power fantasy which exists in Marvel’s world rather than our own real world undermines its hopeful message. But that’s just the view of someone who finds the whole Marvel universe unutterably tedious.

I didn’t much like Steven Spielberg’s Ready Player One (2018) either, even though I spent an inordinate amount of time in the pre-home-computer era playing arcade games with my friends. The big joke in Spielberg’s movie is that the fate of a virtual universe ultimately rests on one of those games. The movie is packed with retro references to old games and movies (an extended riff on The Shining serves once again, as did A.I.: Artificial Intelligence, to show that whatever his aspirations, Spielberg is definitely not the heir to Kubrick). I think my biggest problem with Ready Player One is that the film’s “real world” is just as artificial as its virtual world, a synthetic CG creation which is as weightless as the game world.

Needless to say, all three disks are loaded with self-congratulatory extras in which the filmmakers want to let us know just how amazing their work is.

*

Annihilation (Alex Garland, 2018)

I much preferred Alex Garland’s Annihilation (2018), an eerie, visually compelling piece of science fiction, which like Arrival two years ago focuses on a woman scientist recruited to investigate a mysterious alien visitation. In this case, it’s not a spaceship, but rather an expanding area where something is gradually changing space-time for unknown reasons. Maybe I liked it because it’s a kind of pulp version of Andrei Tarkovsky’s masterpiece Stalker (1979). I haven’t read the source novel by Jeff VanderMeer, but on the evidence of the film, it seems very likely he was influenced by Boris and Arkady Strugatsky’s Roadside Picnic, the basis of Tarkovsky’s film.

A year after her soldier husband left on a secret mission, biologist Lena (Natalie Portman) is surprised when he returns unannounced and strangely changed. Brought in by the military, Lena is reluctantly recruited as part of a team being readied to go where her husband went – into “the shimmer”, a zone from which no one else has ever returned. For unknown reasons, this zone seems more hostile to men, so the new team consists entirely of women.

Once they pass the barrier into the shimmer, they find time and space distorting around them; nature is more vivid there, with plants and animals mutating and each team member’s grasp of reality becoming increasingly unstable. The zone seems to fight their presence as they push on towards the centre – a lighthouse on the coast where Lena finally encounters whatever force is causing these phenomena.

The world inside the shimmer is both hyperreal and mysterious, vividly shot by cinematographer Rob Hardy (who worked previously with Garland on Ex Machina). While the film may be Tarkovsky-lite, unlike the movies mentioned above, it evokes the genuine sense of wonder which has become all too rare in modern sci-fi. The cast is very good and Garland’s direction strong, if perhaps not as original as in Ex Machina; here the epic scale is more impersonal than the intimate psychological exploration of identity in the earlier film.

*

Phantom Thread (Paul Thomas Anderson, 2017)

World-making of a different kind occurs in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread (2017). This seemed like an odd choice of subject for Anderson; even though his work has been pretty eclectic, it has also previously been very American. Yet here, he has immersed himself in a very repressed England still emerging from the traumas of World War Two. The story of Reynolds Woodcock (Daniel Day-Lewis), a deeply self-involved fashion designer who admits a talented young woman named Alma (Vicky Krieps) into his business, despite the disapproval of his controlling sister Cyril (Lesley Manville), the film is almost stiflingly claustrophobic, the world it creates hermetically interior.

The character dynamics among the three are fascinating if ultimately opaque – there’s an unhealthy aura in the London house where they live and work, with possible intimations of suppressed incestuous impulses which are disrupted by the new arrival; has Reynolds introduced Alma to the house to create a buffer between himself and Cyril? If so his decision instead creates disruptions which make him even more irritable and resentful of women than he already was.

The film’s rhythms are rigorous yet languid, adapted to the pace of Reynolds’ life. Ultimately, as Alma grows stronger and more assertive, character motives remain unknowable.

My feelings about Anderson’s work have wavered over the years – his debut, Hard Eight (1996), was a fine character study which showed Anderson’s literary sensibility; Boogie Nights (1997) was a sprawling episodic work which allowed him to flex creatively and play with various styles and tones, while Magnolia (1999) was a very show-offy display of his writing skills which becomes exhausting because the emotional tenor is turned up to eleven from beginning to end, with no breathing room for characters or audience. He pulled back with Punch-Drunk Love (2002), creating a much smaller and more personal film, which also surprisingly revealed that Adam Sandler is actually capable of acting; but then he raised his sights again and tried for an American epic, a big-canvas portrait of rugged individualism and obsessive capitalist greed adapted from Upton Sinclair’s 1926 novel Oil. There Will Be Blood (2007) was too much for me, its portentousness ultimately seeming like inadvertent comedy; it also cemented my antipathy for Daniel Day-Lewis, who – despite being widely considered “the greatest actor of his generation” – has always seemed to me a colossal ham. As soon as he opens his mouth in There Will Be Blood it’s obvious that he’s playing Daniel Plainview as John Huston as Noah Cross in Chinatown; the fact that there are obvious parallels between the two characters only emphasizes the hubris of his choice … and does the film no favours by evoking memories of Polanski’s superior examination of financial and political corruption in American history.

My dislike of the film made me shy away from The Master (2012) when it had its brief theatrical run, but watching it later on disk I regretted that decision. This brilliant, enveloping film (loosely based on L. Ron Hubbard and the invention of Scientology) is one of the great examinations of American character and the attraction to charlatans whose hypocrisy seems justified by the accumulation of wealth. The tension between attraction and repulsion is elegantly dissected by Anderson and seems eerily prescient of the much cruder real-life drama being played out now under the influence of Trump.

Although very different, Inherent Vice (2014) deepened my renewed appreciation of Anderson, and confirmed the appeal for him of the past. His first four films were contemporary, but the last four have all displayed a retreat from the present as if distance helps to clarify things which remain too messy in the present. This adaptation of Thomas Pynchon’s novel has a loose, shaggy-dog charm although it’s set at the time of America’s last great social/political upheaval with the Vietnam War at its height and Watergate around the corner, a time when the choice between radical engagement and personal withdrawal might still seem viable.

With Phantom Thread, Anderson has plunged inward with a vengeance; the world outside Reynolds’ fashion house, with its lingering rationing and radical rethinking of politics (nationalization, the dismantling of empire, the rising power of the working class), has no discernible impact on his life. All that matters to him is designing the new year’s fashions, fashions aimed at the moneyed class rather than those from below who are gaining new financial and political power. Perhaps more than any of his previous films, Phantom Thread comes closest to a rather old-fashioned novel, the cinematic equivalent of something by Henry James or Edith Wharton.

It’s a mysterious and unsettling work which for the first time made me really appreciate Day-Lewis as an actor; Reynolds is in many ways an unpleasant character, but Day-Lewis’ fastidious, finicky and irritable performance is enthralling. A monster of ego, he could have made the film unbearable if not for the strong counterfoils of Manville and, most particularly, Krieps. It’ll definitely be interesting to see where Anderson goes next.

Comments

I had heard of Five years before I saw it. Not unusual in the 80s when you couldn’t see films of interest so easily. What was more unusual is that I first read about Five in a book about Frank Lloyd Wright. Oboler was a Wright fan and the guest house used in the movie was designed by Wright. It’s one of many movies with a Wright house in it. And, in the 80s, I was seeing as many as I could find. So, I was looking for this movie, not because of Arch but because of Frank. I eventually did see it, and I agree, it is a bit of a slog.

I haven’t seen any of the other movies you mentioned, except for Pacific Rim: Uprising, and might not get to them anytime soon. More than enough on my to watch shelves as it is.

Of course, the exterior used for the House on Haunted Hill was a Wright house – with a totally mismatched interior!

The only 3D film we’ve watched that gave me a headache was The Bubble. At the time, I thought it was because almost every scene seemed like a set-piece, with in-your-face 3D. I can generally watch one 3D movie without noticing any effects from the glasses, but not that one. The only other time I can recall getting a headache was the first time we used the 3D glasses and overindulged, including two long 3D fantasy epics.

I remember that first evening well (despite what we drank) … I had notable eyestrain the next day!