Brief comments, part one

It may be apparent to anyone familiar with this blog that I tend to look for links, no matter how tenuous, between the movies I write about. This is no doubt due to a life-long obsession with organizing and categorizing things – books, music, movies, all the t-shirts in my closet. One side effect of this is that quite a few movies that I watch end up “orphaned”, not fitting into a particular post that I’m writing. It isn’t that they’re necessarily less worthy of comment – in fact, some of these films are better, at least more interesting, than ones I have already written about. It’s just that I haven’t found a slot for them.

So here, very briefly, I’ll acknowledge some of these movies in no particular order (though as always there’s a strong temptation to bend them into some overall thematic arc):

Annabelle (John R. Leonetti, 2014)

& Annabelle: Creation (David F. Sandberg, 2017)

I really liked James Wan’s The Conjuring (2013) and, to a slightly lesser degree the 2016 sequel; Wan has a great flair for building atmosphere which gives the periodic jump scares a genuine and lasting kick. They’re two of the best horror movies of the past decade. But I wasn’t thrilled when, reflecting a tiresome new trend, New Line decided to expand those movies into a “Conjuring universe” franchise inspired by Marvel’s commercial behemoth (yet another depressing manifestation of this franchise obsession is Universal’s abortive monster universe which crashed and burned right out of the gate with the disastrous new Tom Cruise Mummy movie). Building not one but two separate features around the creepy doll from the prologue of The Conjuring seemed like a stretch, but Annabelle and its prequel Annabelle: Creation are both fairly entertaining generic horror movies, hampered by the difficulty of taking the Catholic Church and its mythology seriously. (Both on Warner Blu-ray, with multiple featurettes and deleted scenes)

The Day of the Beast (Álex de la Iglesia, 1995)

I’ve known the name Álex de la Iglesia for a long time, but until recently I’d only seen The Oxford Murders (2008), a contrived but entertaining puzzle movie about a grad student and his professor at Oxford University using mathematics to thwart a serial killer. Having seen a reference to his second feature, El Dia de la Bestia (The Day of the Beast, 1995) on-line, I tracked down a copy of the Spanish Blu-ray on eBay and, having watched it, now I’ll have to search for more of his work. This is a gleefully deranged horror comedy in which a priest is convinced that the advent of the Antichrist is imminent and he has just one night to find the mother before she gives birth. In order to do this, he goes on a crash program of crime and moral corruption to make himself attractive to Satan. He begins with petty deeds – stealing change from a crippled beggar, shoplifting – and works his way up to torture and murder. De la Iglesia follows the absurdities of Church doctrine on sin and redemption to their logical conclusions. It’s graphic, occasionally gross, tense and atmospheric and frequently funny. (Spanish 20th Century Fox Blu-ray, with a commentary and a couple of extras, all in Spanish)

Spring (Justin Benson & Aaron Moorhead, 2014)

I ordered a copy of Spring (2014) after being impressed with Justin Benson and Aaron Moorhead’s Resolution and The Endless, two movies which use minimal resources to create a pervading sense of Lovecraftian dread. Spring is their second feature, more ambitious than Resolution and made on a larger scale, but perhaps not quite as effective although it adheres to the same attitude towards supernatural horror – that is, it takes its fantasy elements very seriously and expects its audience to do the same. I always appreciate this kind of sincerity from filmmakers since too many use irony or misplaced comedy to try to get the audience not to laugh inappropriately at potentially absurd ideas. Here, a young American wanting to get away from a messy life, goes to Italy and settles in a small town on the coast, where he becomes attracted to a mysterious woman. Their relationship is intense, but also frustrating as she seems to be holding back some secret which keeps him at a distance despite the obvious passion they share. That secret links their story to ancient myth and affords the filmmakers an opportunity to showcase their considerable skill at creating impressive and disturbing CG effects. (Drafthouse/Anchor Bay Blu-ray, with commentary and numerous behind-the-scenes featurettes)

Exorcist II: The Heretic (John Boorman, 1977)

No doubt it’s a sign of something innately perverse in me, but in 1973 I’d found William Friedkin’s The Exorcist risible (in a century marked by two world wars and multiple genocides, the surest sign of evil is an adolescent girl with a bad case of potty mouth); and perhaps it was in reaction to this that I really liked John Boorman’s much-derided sequel The Heretic (1977). While Friedkin’s movie strove to infuse the Catholic fantasy with a kind of documentary realism, Boorman plunged whole-heartedly into the story as fantasy, creating striking visuals which placed the demonic narrative firmly in an imaginary world. Annoyed by all the bad reviews I read at the time, I even wrote Boorman a letter about how much I liked it and, to my surprise, received a very nice reply saying he was happy that someone appreciated what he had been aiming for. Although in the years since I’ve come to appreciate Friedkin’s movie as a piece of effective filmmaking, I still have a real fondness for Boorman’s sequel, so it was nice to see it again on Scream Factory’s Blu-ray. The two-disk set is packed with extras, including two different versions (the original theatrical and a shorter “home video” cut); two commentaries on the long version, another commentary on the shorter cut; a new interview with Linda Blair in which she hints a lot but avoids coming out to explain why she thought the original script was brilliant and why the finished film is, in her opinion, terrible; a brief interview with editor Tom Priestley; and extensive stills galleries.

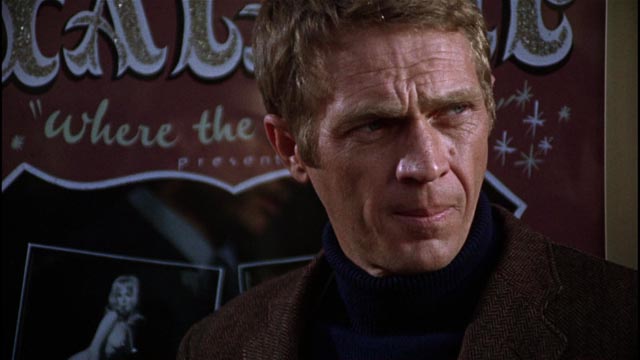

Bullitt (Peter Yates, 1968)

Star Steve McQueen specifically wanted Peter Yates to direct Bullitt (1968) on the strength of Yates’ third British feature, Robbery (1967). That film brought a level of documentary realism to the story of England’s most famous recent crime, the Great Train Robbery, and added in a terrifically well-staged opening car chase through central London. These were qualities which would benefit the story of a San Francisco cop trying to bring down a mob kingpin responsible for the killing of a key witness the cop was protecting. This is a movie I occasionally revisit just for the satisfaction of its stripped-down narrative, McQueen’s charismatic presence, and that lengthy, well-staged car chase sequence (despite the very deserted streets and a highly recognizable VW beetle which appears on every hill throughout the chase). The Warner Blu-ray includes a commentary from Yates, an archival featurette on McQueen, plus two feature-length documentaries, one on McQueen’s career, the other on the craft of film editing.

Vigilante (William Lustig, 1983)

On the heels of his notorious Maniac (1980) and before he hooked up with Larry Cohen for Maniac Cop (1988), Bill Lustig made this effective reworking of Michael Winner’s Death Wish. Apparently New York was just as grim ten years after architect Paul Kersey took to the streets in his grief to kill petty criminals. In Lustig’s take on this story of private justice, the titular vigilante is a working class man whose wife and son are killed by thugs. In Death Wish, Kersey’s targets are random, his attacks aimed at a society which has failed to provide security; in Vigilante, Eddie Marino (Robert Forster) is after the actual guys who destroyed his family, making for a more conventional narrative. As in the movies which preceded and followed it, Lustig is very good at conveying a gritty street-level view of a big city on the brink of collapse. (Blue Underground Blu-ray, with two commentaries)

The Gift (Joel Edgerton, 2015)

Actor, writer and director Joel Edgerton plays a very effective variation here on the story of a seemingly perfect middle-class couple whose lives are up-ended by a deranged stalker. Simon (Jason Bateman) and Robyn (Rebecca Hall) are on the way up; they have a classy house in a rich neighbourhood, he’s in line for a major promotion. A chance encounter with a man from Simon’s past opens cracks in their relationship; Gordo (Edgerton) knew Simon in high school, but his life has obviously gone in a different direction. He seems damaged and now somehow wants to be a part of the couple’s life; he leaves gifts on their doorstep, stops by unexpectedly, begins dropping sinister hints … Simon becomes more aggressive and arrogant in response, while Robyn feels empathy and is reluctant to discourage Gordo. But Edgerton turns the cliche on its head as it’s gradually revealed that Simon is a monster and Gordo is his long-ago victim. Tense and creepy, The Gift is a disturbing and thoroughly satisfying psychological thriller. (D Films Blu-ray, with commentary, deleted scenes, alternate ending, and production featurettes)

The China Syndrome (James Bridges, 1979)

I don’t think I’d seen James Bridges’ The China Syndrome since its theatrical run in 1979, when it got a lot of great publicity from the accident at the Three Mile Island reactor in Pennsylvania. My memory tells me that I found the movie a bit dull, and I was disappointed that it fell short of a full-blown ’70s disaster epic. Watching it again recently, I actually appreciated its restraint. I also had a strong nostalgic feeling for what now seems like the naive faith we all used to have in the power of the media to expose and defeat corporate and political corruption. Like All the President’s Men, it digs into ’70s paranoia but comes up on the (tentative) bright side. (Image Entertainment Blu-ray, with a pair of archival documentaries; the Indicator Blu-ray apparently has a better transfer and a bunch of new extras in addition to the pair on the Image disk)

The First Purge (Gerard McMurray, 2018)

This prequel – the fourth Purge feature – was written by the series’ creator James DeMonaco, but is the first he didn’t direct. But it maintains the best qualities of the series with its focus on a small group of people trying to survive the night of government-sanctioned violence and an increasingly strong subtext about creeping fascism and class warfare. This is even more pointed in the backstory which is fleshed out here, with the fascist New Founding Fathers using the idea of social catharsis as a cover for “thinning out” the undesirable inhabitants of inner cities – here it’s a pilot project on Staten Island, where it becomes clear that most residents just think of it as an opportunity for a big street party until bands of mercenaries show up and begin massacring people. In his second feature, McMurray stages the mayhem effectively and gets good performances from his cast. DeMonaco’s pulp commentary on the current state of the nation seems to be growing more pertinent with each episode. (I’ve read amusing comments on-line which criticize the movies for being too one-sided in their attack on the Right wing in American politics.) (Universal Blu-ray, one alternate scene, and three promo clips so brief they don’t even qualify as featurettes)

Slow West (John Maclean, 2015)

U.S. pop culture has dominated the world for a century or more, so it’s not surprising that people in other countries feel drawn to that most quintessentially American genre, the western. Although what we think of as the West (dusty towns, stagecoaches, gunfights on Main Street, and so on) pretty much existed for only a few decades after the Civil War, in movies it’s a nebulous, timeless era which is at once so specific and so generalized that it provides a capacious conceptual space within which America has forged one of the central myths of national identity: the individual’s absolute right to self-determination through the personal exercise of righteous violence. It’s a myth which leaves little room for a true sense of community, of common interests which supersede personal desires. It’s a myth whose arrogance and destructive essence has made the U.S. the deadly gun-choked nation it is today.

And yet, people who have been born and raised in more constrained societies are drawn to this violent era and non-American filmmakers attempt to explore the appeal and contradictions of the genre, from Sergio Leone and other Italians who amplified the mythic qualities in spaghetti westerns to the Danish Kristian Levring with The Salvation (2014), filmed in South Africa, and the English John Maclean with Slow West (2015), filmed in New Zealand. Maclean’s film (which he also wrote) tries for the mythic poetry of Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man (1995), with this story of a naive Scottish boy who finds his way to the West in search of the girl he loves, who fled Scotland with her father. He joins up with a gunman who offers to help him for cash, and together they journey through mountains, forests and deserts, encountering an odd array of people, meeting with and committing violence, until the boy’s journey ends tragically in disillusionment and death. The cast – Kodi Smit-McPhee, Michael Fassbender, Ben Mendelsohn – is very good, the landscapes spectacular, the tone finely balanced between menace, melancholy and humour … but in the end, it all feels light and insubstantial, the myth drifting away like a wisp of smoke. (Mongrel Media Blu-ray, with interviews and a behind-the-scenes featurette)

To be continued …

Comments