Brief comments, part two

Blade of the Immortal & As the Gods Will

(Takashi Miike, 2017/2014)

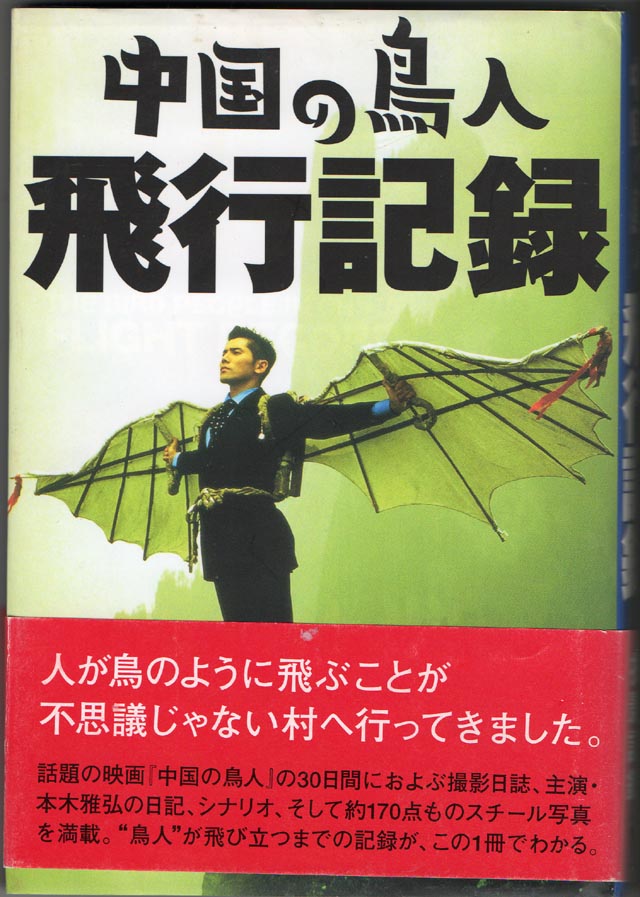

Takashi Miike has made over a hundred movies in less than three decades, tackling pretty much every genre available, ranging from tragedy to comedy to kids’ fantasy … and even a Japanese “spaghetti western”. In his early days, he was aggressively transgressive, pushing the boundaries of what was permissible even in Japanese V-Cinema. He made a lot of violent gangster movies, often blending absurdist and fantasy elements into them (which reminds me, I have Arrow’s Blu-ray releases of both the Black Society and the Dead or Alive trilogies, which I haven’t got around to watching yet). The first Miike movie I ever saw was The Bird People in China (1998)[1], about a yakuza who is transformed by a journey into a remote area of China where legend has it that the people can fly. He had his international breakthrough with the unsettling thriller Audition (1999), but that success didn’t tame him – in fact, just two years later he made his two most outrageously disturbing films, Visitor Q and Ichi the Killer (both 2001). Since then he has made more yakuza movies, branched out into samurai films, high school violence, generic horror (One Missed Call) and even kid-friendly (yet still disturbing) fantasies like Zebraman and The Great Yokai War. But the culture has caught up with Miike and, while the violence is still there, his movies no longer feel dangerous. Not surprisingly, though, his more recent work is confident and polished and he is still able to apply himself to a wide range of material – like the samurai fantasy Blade of the Immortal (2017, based on the manga by Hiroaki Samura), in which a mysterious old crone saves a dying man after a big, bloody fight. She infects him with blood worms, which heal his wounds and make him unkillable, even though he still suffers and feels pain. Fifty years later, he becomes involved with a young girl who is seeking revenge against an anarchist band of swordsmen who killed her father, leading to a huge, extended battle of three against hundreds. Miike plays it straight despite the fantasy element. (TVA Blu-ray, with interviews and a behind-the-scenes featurette about filming the big battle.)

But he goes for all-out craziness in As the Gods Will (2014), a kind of blend of Battle Royale and live video game. School kids around the world find themselves drafted unwillingly into a series of challenges in which they must solve a puzzle or die. The film opens with what turns out to be the high point, with a classroom trapped by a malevolent Daruma doll which causes anyone who moves when he’s looking to explode in a shower of blood beads. Miike gets the mix of horror and humour just right here, but what follows is essentially a series of repetitions of this sequence, with the same kind of deadly challenges whittling away at the dwindling group of survivors. The rationale for the games is unclear – there seems to be something to do with aliens, but there’s also the thing about hero Shun praying to God to make his life more exciting because he’s so bored. The whole thing (based on a manga by Muneyuki Kaneshiro and Akeji Fujimura) exists solely to provide an excuse for the murderously funny challenges – despite some sketched-in back stories, it never engages with the characters on the level of Battle Royale, so as a viewer you don’t feel much when any of them die. (Funimation Blu-ray, with no extras.)

Braven (Lin Oeding, 2018)

It’s a bit of a stretch to believe Jason Momoa is a regular family guy running a logging business in Alaska, but Braven (2018) is a pretty good generic thriller set against wintry mountain scenery. Joe Braven (Momoa) is just trying to keep things together as he deals with business, wife, young daughter, and a tough father who is slipping deeper into dementia. In trying to deal with the latter, he takes dad to a remote cabin to address the need for him to be institutionalized because he’s becoming too dangerous to himself and others. What he doesn’t know is that one of his employees, who’s been running drugs for gangsters in his logging truck, has hidden a big stash of coke in the cabin and the bad guys are on their way to retrieve it. Before long, wife and daughter are caught up in the situation, and it’s a fight for the family’s life. Efficiently directed by stunt coordinator Lin Oeding, Braven is nothing remarkable, but it’s a passable time-waster, with Stephen Lang as reliable as ever as the dad who knows he’s slipping away and is very angry about it. (I picked this up as a fan of Marcus Nispel’s Conan the Barbarian [2011], in which Momoa starred as a much better version of Robert E. Howard’s hero than Arnold Schwarzenegger.) (VVS Films Blu-ray, with a couple of brief featurettes.)

Iron Monkey (Yuen Woo-ping, 1993)

Yuen Woo-ping was a major figure in Hong Kong cinema long before Quentin Tarantino and the Wachowskis hired him for his particular skills as a martial arts fight coordinator for the Kill Bill and Matrix movies. Yuen had been acting, directing and stunt coordinating since the early 1970s, and his style of action had been a key force in shaping martial arts cinema – complex, kinetic and often laced with humour. As a director, he did a great deal to define Jackie Chan’s on-screen persona in early films like Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow and Drunken Master (both 1978). In the latter, Chan played Wong Fei-hung, a fictionalized version of a real doctor and martial artist (1847-1924). Fei-hung, a popular folk hero, has turned up in countless movies and television shows. He’s also present in Yuen’s Iron Monkey (1993), though as a boy; the main character is his father, Wong Kei-ying (Donnie Yen), a doctor who is mistaken by corrupt officials for the masked bandit Iron Monkey. When it becomes clear that the bandit is someone else, the officials threaten Fei-hung in order to force Kei-ying to hunt him down. Iron Monkey (Yu Rong-kwong) is another doctor, one who steals from officials in order to help the poor, and Kei-ying inevitably ends up joining him in his fight against an oppressive ruling class. This Robin Hood story is well-told by Yuen and the martial arts action is impressive and plentiful. Although historically Hong Kong movies have not generally been well preserved, the 2K restoration on Eureka’s Blu-ray is quite spectacular. (Eureka region B Blu-ray, with two-and-a-half hours of interviews and featurettes. The disk features the full-length film, rather than the Miramax-shortened U.S. cut available on the region A disk.)

Play Dirty (André De Toth, 1968)

André De Toth, the one-eyed director who made one of the finest 3-D movies of the first wave, House of Wax (1953), was nothing if not versatile. In a career which spanned thirty years, he made many tightly-constructed, tough-minded movies, particularly westerns and film noirs. To cap his career, he made this grim and gritty war movie, steeped in late-’60s cynicism about war but devoid of the sneering jokiness of The Dirty Dozen, released the previous year. Set in the North African desert, it pits a brutally pragmatic officer known for getting his men killed on impossible missions against a naive career officer on a mission to go hundreds of miles behind enemy lines to destroy Rommel’s fuel dump. The cynic, Captain Cyril Leach (Nigel Davenport), is openly contemptuous of Captain Douglas (Michael Caine), the man ostensibly put in charge of the task. Their antagonism leads to mistakes as they deal with the harsh landscape and occasional encounters with the enemy, but gradually they come together in order to complete the mission … the terms of which drastically change when British commanders decide they want to preserve the fuel dump for their own use when the tide turns against Rommel. The Brits betray the commando unit to the Germans in order to stop them fulfilling their mission. De Toth emphasizes the gruelling physical and psychological stresses the men confront on their journey, their efforts to survive ultimately futile. (Twilight Time Blu-ray, with an excellent transfer but unfortunately no extras.)

Serpico (Sidney Lumet, 1973)

I hadn’t seen Sidney Lumet’s Serpico (1973) in years and, watching it again on Blu-ray, I was reminded of just how good it is … in fact one of Lumet’s finest achievements. Ripped from the headlines, as they say, the movie was made just two years after the near fatal shooting with which it opens. Frank Serpico was an idealistic police academy graduate in 1959, but a decade later he was despised by his fellow New York cops because he refused to go on the take like so many others. His honesty paradoxically made him “untrustworthy”. He was moved around the department, manipulated by various authorities who either wanted him to help expose corruption or wanted to sidetrack him in order to conceal that same corruption. It seemed quite clear that he was set up for the shooting, but he didn’t die and as he recovered he finally went public with his evidence of widespread corruption, forcing Mayor John Lindsay to establish a commission to clean up the police department. Lumet, working from a script by Waldo Salt and Norman Wexler based on Peter Maas’ book, creates a vivid portrait of the city and the police department, always keeping his focus on the psychological and moral conflicts which are tearing Serpico apart. Although Al Pacino had already done The Godfather, this is the movie that made him a star. (Paramount Blu-ray, with a half-hour’s worth of featurettes.)

Invisible Man Collection (Various, 1933-51)

James Whale’s 1933 version of H.G. Wells’ The Invisible Man is, along with The Old Dark House, my favourite among his films. Witty, tightly constructed, it maintains a nice balance between psychological horror and comedy. The unseen Claude Rains makes a strong impression in a debut performance which relies almost entirely on voice alone. And even today John P. Fulton’s invisibility effects are really impressive. Fulton was the only common factor throughout Universal’s series of films about invisibility, none of which matched the quality of Whale’s original in anything except the effects. Other than the risk of the invisibility drug driving its user insane, there’s no connection between the films – in the first sequel, The Invisible Man Returns (made seven years after the original), a man wrongly accused of murder uses the drug to escape death row and find the real killer; The Invisible Woman (also 1940) aims for comedy; Invisible Agent (1942) sends a man behind enemy lines to secure secret plans, though he spends a lot of time flirting with his female contact and doing stupid things to make his presence known to the Nazis; in The Invisible Man’s Revenge (1944), a man uses the drug to get revenge on a couple who cheated him out of his share in an African diamond mine. Another seven years passed before the Invisible Man met Bud Abbott and Lou Costello in one of their weakest “meet a Universal monster” movies. Despite the unevenness of the series, the upgrade to the Universal/BFI Blu-ray set was well worth it as the hi-def resolution makes the effects even more impressive than they looked on DVD. The set includes the same extras as the 2004 Legacy Collection DVD set, plus the addition of the Abbott and Costello feature.

All the Money in the World (Ridley Scott, 2017)

One of the main points of interest about Ridley Scott’s All the Money in the World (2017) is the last minute recasting of the pivotal role of John Paul Getty literally just before the film’s release. When Kevin Spacey fell from grace, Scott cut him out and re-shot all his scenes with Christopher Plummer. It was a remarkable job and the seams certainly don’t show; and given the quality of Plummer’s performance, it’s hard to see how Spacey, a very different actor, would have fitted in. Plummer captures Getty’s creepy egotistical greed to perfection. Based on the true story of Getty’s chilling response to the kidnapping of his grandson in Italy in 1973, the film is a study in how money distorts human nature and relationships. The cast is fine – Michelle Williams as Gail Harris, John Paul Getty III’s mother; Charlie Plummer (no relation) as the boy; Mark Walberg as the old man’s fixer who eventually grows a conscience; Romain Duris as a sympathetic kidnapper … but I’m afraid I found the film a bit flat having recently heard the whole story on The Dollop podcast, where it came across as far crazier and more terrifying; the podcast went into much more detail about Getty III’s experiences in captivity, while the movie concentrates on the conflict between Gail and the old man. (TriStar Pictures Blu-ray, with deleted scenes (sadly none with Spacey for comparison) and several featurettes on the case and the making of the film.)

Postal (Uwe Boll, 2007)

I saw House of the Dead and Alone in the Dark back in the early 2000s and pretty much agreed with what I’d read about them: mediocre video game-based movies that were disposable and forgettable. I quickly became aware of Uwe Boll’s reputation as “the worst living filmmaker”, though there seemed to be much better candidates, and I didn’t bother to see any of his subsequent movies until I came across a rental copy of 1968 Tunnel Rats (2008), which turned out to be a grim, claustrophobic nightmare of a war film about U.S. soldiers fighting the Vietcong in a network of underground tunnels. It seemed quite impressive to me, but because of his reputation it received generally lousy reviews – as with M. Night Shyamalan, his reputation perhaps colours the way people watch his movies (not that I think Boll is in Shyamalan’s class). Still, I didn’t bother to follow it up with any of Boll’s other movies.

Then a few weeks ago I watched Josh Olson’s enthusiastic Trailers From Hell commentary on Postal (2007) and ordered a cheap copy from an Amazon seller. Boll, co-writer as well as producer-director, throws pretty much everything at the wall here, outraged by what he sees as a universal, interconnected system of hypocrisy and greed in which those in power and in opposition all benefit from the political and economic horrors that seem to have overwhelmed the world in the past few decades – adherents to established religions and cynically concocted cults, governments and terrorists, capitalists and entertainers all jockey for position in a corrupt social and economic order which exploits and abuses ordinary people who are just struggling to get by. It’s a scattershot film which is determined to offend as many people as possible and, surprisingly, a lot of it works. Listening to Boll’s commentary track, and a recent episode of the Trailers From Hell podcast The Movies That Made Me which featured Boll, he turns out to be an interesting guy whose reputation has made him extremely opinionated and combative. I’m not sure I’ll search out any more of his work[2], but Postal was definitely worth a look. (Peace Arch Entertainment Blu-ray, with commentary and a couple of brief featurettes – one of which is footage of Boll boxing several of his critics.)

_______________________________________________________________

(1.) I first saw it on VHS, the tape lent to me by my late friend Terry Coles who was negotiating North American rights to the film for her fledgling distribution company (unfortunately the deal was never sealed). Following Terry’s death ten years ago, I acquired a treasured memento – her copy of a small, colourful promotional hardcover book for the film. As far as I can tell (it’s all in Japanese), the book contains an account of the production, the people involved … and the script, along with tons of photos and production sketches. It’s a lovely artifact. (return)

(2.) Having said that, a few days later, I found a used copy of Boll’s Assault on Wall Street (2013) for a couple of bucks. The first half is actually a very good, intense depiction of an ordinary working guy who discovers, while dealing with the rising costs of his wife’s long-term cancer treatment, that he’s lost all his money through the corrupt financial system which brought on the 2008 collapse. With every new detail, his powerlessness increases while the people who screw him over never pay a price themselves. Pushed into an impossible corner, he uses the skills he learned in the military to exact personal justice against investment brokers, bankers and a legal system which protects white collar criminals rather than their victims. This second half is less well made than the first, with choppy editing and sequences which are repetitive rather than cumulative. But the furious social commentary of the first half is dramatically powerful. (Phase 4 Films Blu-ray, with making of featurette and a commentary from Boll.) (return)

Comments