David Byrne’s True Stories (1986): Criterion Blu-ray review

I became an instant fan of Talking Heads when I first heard their third studio album, Fear of Music, in 1979. Living far from any major musical centre, I had little experience of Punk and New Wave and the Heads seemed like something very new to me after a decade of mainstream and progressive rock. The sound was infectiously catchy, related to dance pop, yet there were layers of something darker beneath the surface – the effect was somehow exuberantly apocalyptic, as if cheerfully embracing the imminent end of the world.

With ever-increasing infusions of World Music, the darkness seemed gradually to recede in subsequent albums. David Byrne’s frontman persona had a kind of cultivated naivete, a guilelessness which might have become cloying if allied with a less forceful musical talent. Despite a lyrical awareness of the darker corners of human existence, a sense of optimism runs through the music of Talking Heads and Byrne in his post-Heads incarnations.

As so often happens with bands, Talking Heads fell increasingly under the influence of the most dominant member and by the mid-1980s Byrne was branching out as an independent creative force. That was when he directed his one and only dramatic feature, True Stories (1986), for which he wrote a collection of character-based songs which were then “covered” by the band for their seventh studio album. One more album followed (Naked, 1988) before the band officially broke up in 1991.

As a solo project, True Stories clearly illustrates the extent of Byrne’s creative dominance over Talking Heads. The score is an eclectic mixture of musical styles – Tex-Mex, pop ballad, folk, R&B – which provide metaphorical glue for a portrait of smalltown American life which encompasses a multi-racial, -ethnic and -class mosaic held together by the essential decency and good will of ordinary people. The film’s soundtrack goes further into a kind of loving embrace of flawed individuals and away from larger, darker themes.

In other words, True Stories is a utopian vision of America as it would like to see itself, the mythic melting pot in which it’s possible for anyone to achieve fulfillment of their personal dreams. It’s perhaps not irrelevant that Byrne himself is an immigrant – born in Scotland, moving to Canada when he was two, then six years later to the States. His movie offers a dream image of the promise held out to the world by an idealized U.S.

Working loosely from a script by actor Steven Tobolowsky and writer Beth Henley (Crimes of the Heart), Byrne combines a fascination with individual idiosyncrasies and a seemingly loose, improvisational exploration of the ways in which individuals form connections and build a shared community. Byrne acknowledges the influence of Robert Altman, in particular Nashville (he initially approached that film’s writer Joan Tewkesbury to write the script), but Byrne is completely devoid of Altman’s cynicism and there isn’t a trace of cruelty or condescension in his treatment of the characters who populate the fictional town of Virgil, Texas.

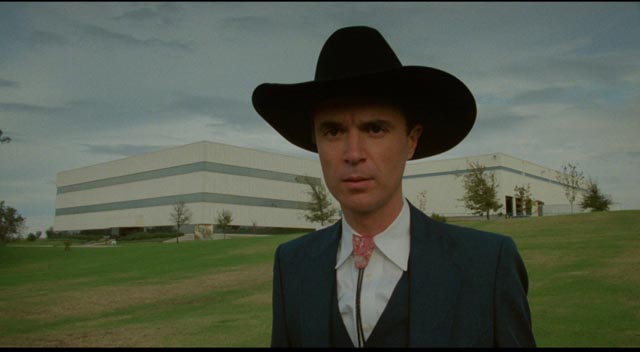

While True Stories harks back to the loose, rambling, multi-character structure of Nashville, it also points ahead to the comedic mock-documentaries of Christopher Guest, particularly Guest’s Waiting For Guffman (1996). As a wide-eyed visitor to Virgil, fascinated by everyone he meets and everything he sees, Byrne himself as the on-screen Narrator ties all the threads together during the week leading up to a local talent show celebrating the state’s sesquicentennial.

A number of characters emerge from the fabric of the town – Spalding Gray and Annie McEnroe as the Culvers, a happily married couple who haven’t spoken to one another for years; Tito Larriva as Ramon, an assembly-line worker in Mr. Culver’s electronics factory (the town’s main industry), who plays music in a local bar at night; Jo Harvey Allen as a woman who endlessly tells tall stories about her life; Alix Elias as a woman who banishes anything sad from her life; Swoosie Kurtz’s Miss Rollings, a rich woman who hasn’t gotten out of bed in years simply because lying there, eating and watching television, is satisfying enough for her; Roebuck “Pops” Staples (of the Staple Singers) as Mr. Tucker, a benevolent practitioner of Voodoo. But John Goodman as Louis Fyne emerges in a break-out performance as the loose narrative’s protagonist, an amiable guy who resorts to advertising on TV and putting a billboard in his front yard in hopes of finding a wife. A big guy who manages a deep sadness by projecting a forced cheerfulness into the world, he becomes the Narrator’s closest local connection on the way to his climactic performance at the Friday night talent show.

Drawing on the work of experimental theatre director Robert Wilson, Byrne uses the concept of “knee plays”, seemingly disconnected, inconsequential interludes, to disrupt any risk that the film will slip into anything like a conventional narrative. These odd moments evoke the possibility of transcendence, expressing something rich and mysterious which may break through the mundane surface of life at unexpected moments – Ramon interrupting the assembly line to display his ability to “tune in” to others’ inner thoughts; a group of 4H kids walking through an empty lot, breaking out into a rhythmic chant as they beat time on odd scraps of wood; a security guard walking out onto the half-built stage in the middle of an empty field and breaking out into an operatic aria; the opening and closing images of a young girl performing a kind of private ritual dance on a dirt road which stretches away to a distant flat horizon. These moments tell us that a creative impulse runs through everyone at all times, that it can break out spontaneously anywhere and any time for no other reason than that joy needs to express itself.

Shot by Ed Lachman in a kind of hyperreal naturalism, the film is visually reminiscent of Terrence Malick’s Badlands with its saturated colours and pure light – though here rather than contrasting with a darkness lurking beneath that clarity, the luminous visual quality expresses a purity inherent in the physical and social landscape.

Byrne’s view of America is imbued with warmth and charm, aided by a collection of wonderful performances and musical numbers which range from the energetic club lipsync Wild Wild Life to the wistful Dream Operator sung by Annie McEnroe to accompany an increasingly outlandish local fashion show; to Puzzlin’ Evidence, a rousing Gospel anthem to political paranoia performed in a church; to Tito Larriva’s club rendition of Radio Head; to my favourite moment in the movie, “Pops” Staples’ ritual invocation through dance and song of the power of Papa Legba to bring happiness to Louis.

The clearest influence of Nashville is apparent in the culmination of the various threads in the talent show, where Louis’ anthemic People Like Us echoes Barbara Harris’ It Don’t Worry Me; both songs reflect an inward-turning tendency which rejects larger, more difficult social issues in favour of a sense of personal comfort, a valorization of the individual over the political. Louis’ plea for personal happiness (“We don’t want freedom, we don’t want justice, we just want someone to love”) is, thanks to the invocation of Papa Legba, rewarded when Miss Rollings sees his performance on TV and is moved to get out of bed to answer his call for love.

Although it gives the film a satisfying emotional conclusion, this rather sweet expression of the American myth of individualism makes me slightly uncomfortable. Though less strident than the ending of Nashville (there’s no traumatic act of violence to tie the threads together), it still reflects a willful turning away from the messy complications of the world we actually live in in favour of the small comforts of a personal life insulated from larger conflicts.

True Stories is steeped in charm and humour and good-natured generosity, and as a veritable catalogue of Byrne’s eclectic musical interests it informs much of his subsequent, post-Talking Heads work.

*

The Disk

Criterion’s Blu-ray uses a 4K restoration as the basis of a beautiful image; colours are rich and contrast is strong. The 5.1 soundtrack brings out all the nuances of Byrne’s score and the varied vocals provided by the actors themselves. The complete score is included on a separate CD which comes with the Blu-ray.

The supplements

There are several supplements which focus on the film’s production and Byrne’s creative work, including an archival behind-the-scenes documentary, Real Life (1986, 31:29) by Pamela Yates and Newton Thomas Sigel. This plus seven deleted scenes (14:18) and a very brief intro from Byrne (:23) are all from lo-res video sources.

No Time to Look Back (11:46) is a new piece by Bill and Turner Ross revisiting the film’s locations, and there’s a brief documentary about designer Tibor Kalman (11:49) who created the film’s titles and closing credits, as well as many Talking Heads album covers.

The most substantial extra is a new documentary created by Criterion about the making of the film (1:03:48), in which many of the people involved in the production look back at the collaborative creative process presided over by Byrne.

There’s also a (lo-res) trailer (2:28) and a more substantial than usual insert booklet in the form of a tabloid newspaper, which includes essays by critic Rebecca Bengal, journalist Joe Nick Patoski, and Byrne himself, plus a 1986 article by Spalding Gray and a selection of Weekly World News articles which were the source of some of the film’s storylines.

Comments

Have seen about 2000 movies in my life so far

True stories is probably my favourite.

I simply love it.