Julien Duvivier’s Panique (1946): Criterion Blu-ray review

Three years ago, Criterion made a major step in reviving the reputation of Julien Duvivier with the release of a four-disk Eclipse boxed set of the director’s work from the 1930s, the most fertile period of a career which spanned from 1919 to 1967. During that decade, the eclectic Duvivier was ranked with the masters of French cinema – Jean Renoir, Marcel Carne, Jacques Feyder and Rene Clair. Like Renoir, Duvivier left for Hollywood as the Second World War loomed and made six features in the U.S., beginning with a remake of his own Un carnet de bal (1937).

When he returned to France after the war, he found that his reputation was now tarnished – there was resentment towards those who had “abandoned” France during the Occupation; but those who had stayed and continued to work also faced problems with accusations of collaboration. For some years following the liberation, the country struggled to come to terms with the complicated legacy of life under the Germans.

After several false starts, Duvivier began to shoot his first post-war feature in January 1946 and, as it turned out, his choice of material did nothing to ease the negative opinion of critics and audiences. Adapted from one of Georges Simenon’s non-Maigret novels, Panique (1946) is a startlingly dark depiction of French society as a breeding ground for criminality, prejudice and misdirected “righteous” violence. Despite a non-specific period setting (there’s no mention of the recent war), the bitter scapegoating of a vaguely perceived “other” couldn’t help but evoke memories of the treatment of French Jews during the war years – a community clinging together to define itself in opposition to someone who doesn’t really belong.

I haven’t read the Simenon novel (and it’s almost thirty years since I saw Patrice Leconte’s apparently more faithful adaptation, Monsieur Hire [1989]), but according to comments in the extras on the new Criterion release, Duvivier and co-writer Charles Spaak pushed the material into darker, more cynical territory. Panique is bitter Gallic noir, made with passionate conviction and a complete absence of the romantic underpinnings of the French poetic realism of the previous decade (epitomized by films like Carne’s Port of Shadows [1938]).

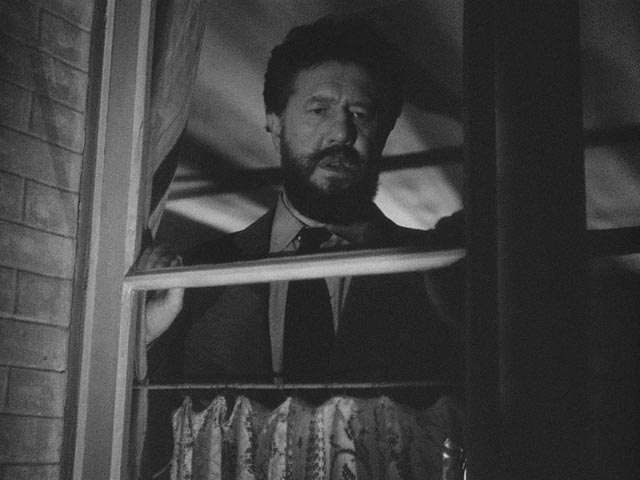

There are no positive characters in Panique. We initially meet M. Hire (Michel Simon, in one of his most restrained performances), a dark, cynical, anti-social man who lives in a Paris neighbourhood where people seem prone to gossip quite openly about one another. Buying a cut of meat from the local butcher, M. Hire complains that the meat is not bloody enough, while outside in the rather bleak, undeveloped square, garbage collectors discover a woman’s body among the trash. As the locals all rush to get a look, M. Hire comments to the butcher that “carrion attracts flies”.

We next meet Alice (Viviane Romance), a woman who has just returned from prison where she served a sentence for her lover’s crime. That lover, Alfred (Paul Bernard), is a petty criminal who struts arrogantly about the neighbourhood. When he sees Alice in the aftermath of the fuss over the body, he tells her to pretend that she doesn’t know him – the police know she was covering for someone and are watching her to see if she’ll expose the real criminal; they must meet by “accident” the next day and begin a “new” romance as strangers.

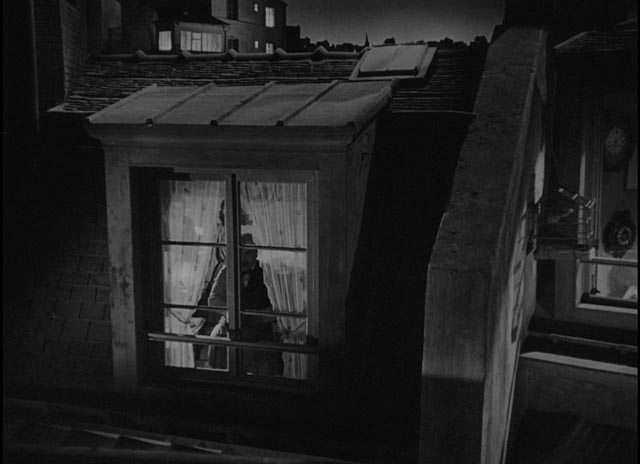

Alice takes a room in a residential hotel on the square and discovers that M. Hire’s window overlooks hers. When she sees him watching her undress, she merely closes the windows in irritation. But the next day, as she and Alfred restart their relationship in public – among the crowds at a carnival which has set up in the square – she spots M. Hire trailing them. This leads to the most technically audacious sequence in a film full of self-assured camerawork. Alice and Alfred decide to take a ride in the bumper cars and M. Hire follows; he’s the only single driver among couples who are much younger than him, and when Alfred and Alice aggressively target his car, the other couples gradually join in the fun, ganging up on the older man. With cameras attached to the cars, the savagery of the “hunting pack” going after their prey takes on a dynamic and visceral air of violence which presages the eventual outcome of the story.

Later, M. Hire corners Alice on the hotel staircase and tells her he is concerned for her safety because he has proof that it was Alfred who killed the woman in the square. When she and Alfred are alone together in her room, she tries to draw him out … and he freely admits that he killed the older woman for her money. But instead of being repelled, Alice reasserts her love for Alfred and together they begin to scheme about how to protect themselves from M. Hire.

Alice turns out to be a quintessential femme fatale, worming her way into M. Hire’s confidence the better to trap him. The pair use the neighbourhood’s dislike of the aloof, unfriendly man to create a rising swell of distrust, shifting suspicion for the murder onto him.

With relentless narrative logic, Duvivier lays out the steps by which a social group can be lead to turn its irrational fear on someone whose superficial differences mark him as an outsider. In a revealing scene M. Hire exposes his vulnerability to Alice, evoking audience empathy while providing her with further ammunition to be used to destroy him. The genuine criminals pass unnoticed among their neighbours because they look like everyone else, in fact appear to be an attractive and appealing couple, while M. Hire seems deliberately to attract hostility with his disregard for accepted social norms.

Shot on a vast outdoor set constructed at the Victorine studios in Nice, much of the film takes place in bright sunshine, yet it creates an air of claustrophobia. Duvivier’s camera prowls and swoops among the buildings, peering through windows and looking down on the inhabitants with an entomologist’s detachment. His frequent use of a crane suggests that he brought much of what he learned in Hollywood back to France with him. The frequently exhilarating visuals provide an ironic counterpoint to the increasingly cramped emotional environment of the story.

The critics and filmmakers of the nouvelle vague dismissed Duvivier as something of a hack – his body of work was too varied to support a clear auteurist interpretation – and yet Panique, which Duvivier himself believed to be a his finest work, embodies a ferociously assured view of the unpleasantness human groups are capable of. The people of this neighbourhood, only too willing to believe the worst of each other, are easily manipulated by a pair of schemers intent on protecting themselves by destroying another.

*

The disk

The image on Criterion’s Blu-ray is quite stunning; the film-like texture enhances the movie’s atmosphere with strong contrast and a great deal of detail in both the sunlit exteriors and the shadowy, noirish interiors. Much of the film is sharp, but there are some shots which are deliberately soft; interestingly, in the intimate scene between Alice and Alfred in the shadows outside a church as they plan their “accidental” meeting, Romance’s closeups have the gauzy softness typical of Hollywood studio films of the period – an attempt to be flattering to the actress – but the closeups of Bernard are equally soft, almost as if deliberately parodying the technique to mock its misleading artificiality.

The 2K restoration was sourced from a 35mm fine-grain source. The audio shows its age more than the image, but is nonetheless very clear.

The supplements

There are three informative extras on the disk, beginning with an odd but interesting interview with Bruce Goldstein about the history and art of subtitling (20:56). As someone who has some experience of writing subtitles for documentaries that I’ve worked on, I could appreciate much of what Goldstein has to say – in particular the need to write the essence of what is being said without providing a literal translation (there are several interesting clips in which such a literal translation is provided for scenes from Panique and other movies, with the screen necessarily filled with text to get every word in).

Then there’s an interview with Pierre Simenon, Georges Simenon’s son (15:40), in which he talks about his father’s work, about the problems of translating those works to film and his father’s opinions about some of those adaptations.

Finally, there’s a conversation between critics Guillemette Odicino and Eric Libiot (20:08) about Duvivier’s career and the fluctuations his reputation has gone through over the years.

There’s also a trailer for the restoration (2:07) and an insert with a pair of essays about Duvivier and the film by James Quandt and subtitle translator Lenny Borger.

Comments