Elaine May’s Mikey and Nicky (1976): Criterion Blu-ray review

Elaine May has prodigious talents which seem to have been underused in the film business. A gifted comedian, writer, improvisatory performer (particularly as half of the hugely influential Nichols and May comedy team in the late 1950s), she turned to directing after a few movie roles in the late ’60s, becoming only the third woman to direct for a Hollywood studio since sound came in (after Dorothy Arzner and Ida Lupino). But even from the start, her relationship with the front office was rocky and her first feature, A New Leaf (1971, adapted by May from a story by Jack Ritchie), was taken from her and re-edited by Paramount (her cut ran about three hours; theirs eighty minutes less). But despite these problems, the film was well-received.

Her second feature, The Heartbreak Kid (1972, scripted by Neil Simon from a Bruce Jay Friedman story), was an even bigger success and it appeared that May was on her way to establishing a career as a director of offbeat romantic comedies. But things changed with her next project, Mikey and Nicky (1976), whose production dragged on for two years, going well over budget, and eventually being dumped by Paramount – which simply didn’t understand the movie – for a brief, unsuccessful Christmas opening. May’s conflicts with the studio this time involved her stashing away reels of negative to prevent the studio taking the film away from her again. Although she did manage to finish it her way, it was only after four more years, when she and distributor Julian Schlossberg bought the film back from Paramount and re-released it in 1980, that it began to be recognized as a brilliant piece of work.

But the damage to her career was considerable and it wasn’t until 1987 that she released her fourth (and final) feature, another film which went way over schedule and over budget. That film, a comedy conceived on an epic scale, was greeted with near-universal derision – for a number of reasons, not least for those production difficulties; as frequently happens, Ishtar (1987) was reviewed more for its bloated budget than for its actual qualities as a movie.

But there is something perhaps more crucial in May’s work which makes critics and audiences uncomfortable and increasingly unreceptive: at the centre of each of her films are complicated and problematic male characters. These films are vehicles for a deeply unsettling dissection and analysis of masculinity – and it’s hard not to suspect that within a hyper-masculine industry these portraits of deeply flawed men being drawn by a woman were not particularly welcome.

Mikey and Nicky is the cornerstone of May’s brief filmography, a deeply personal work rooted in her own experience growing up in Philadelphia where as a child she knew and heard stories about local hoods. One story in particular stuck with her – of a guy who had to set up his friend for a hit – and she worked on the story for years before eventually turning it into a film script. It’s a dark and frightening portrait of desperate characters living on the fringes, clinging to a lower middle class existence supported by small-time grifting. In May’s other films, the darkness of her view of masculinity is leavened by comedic trappings; here she descends completely into that darkness and reveals so many layers and nuances that viewers are forced continually to re-evaluate their feelings for the characters.

As embodied by Pater Falk and John Cassavetes – both doing some of the finest work of their careers – they evoke empathy, sympathy, repulsion and horror in equal degrees, and sometimes simultaneously. Although it might be possible to view the film as akin to, say, Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets (1973) as an examination of small-time criminal outsiders, May’s work eschews Scorsese’s self-conscious technique and mythologizing which can’t help but romanticize his characters’ tragic masculinity. There is no romanticizing of Mikey and Nicky, just a sweaty desperation barely held in check by the trappings of middle-class materialism and an enacting of gender roles which are ill-fitting and break apart under the stresses of a single fraught night.

Nicky (Cassavetes) is a bookie who works for mobster Dave Resnick (Sanford Meisner) and he’s made the mistake of stealing from his boss. His bookie partner has already been killed and Nicky knows he’s targeted for a hit himself. Desperate and paranoid, hiding out in a seedy hotel room, he calls his childhood friend Mikey (Falk) to come and help him out … but when Mikey shows up Nicky doesn’t even trust him. This opening sequence, in which Mikey patiently tries to calm and reassure Nicky, offering him medicine for the pain of an ulcer, promising to help him get away, has the tone of a fractured love story. There are bonds between the two which reach back to childhood – but as the night progresses we learn that those bonds are tightly intertwined with more complicated feelings, envy and resentment, and May gradually exposes the conflicted nature of all close relationships – the negotiations and suspicions and vulnerabilities which genuine emotional attachment tentatively holds together.

Mikey admires and resents Nicky’s easy sociability, his self-assurance, which nonetheless makes his friend more dangerous, more provocative (there’s a tense scene in a bar where Nicky, feeling invulnerable, provokes the Black patrons). Mikey is more contained, more tentative, and we learn that his own father liked Nicky better, as does their mutual boss Resnick. And yet, while we quickly learn that Mikey is here to set Nicky, his best friend, up for a hit, trying to expose him to hitman Kinney (Ned Beatty), we also sense that his promises to help Nicky get away – even to escape with him – are emotionally genuine. Betrayal is really only betrayal when there are real bonds between betrayer and betrayed and that’s what makes it tragic.

In and around the central action – Mikey’s efforts to control and contain the increasingly volatile Nicky as he waits for Kinney to show up at various locations (always too late because he’s not that familiar with the city) – May weaves various other threads which deepen and enrich the film’s themes, often in extremely uncomfortable ways. The film was disliked by some feminists for its problematic depiction of the three women the pair encounter over the course of the night and undeniably these three are vulnerable, abused and stripped of agency. But they are entirely plausible in this milieu – what self-respecting independent woman would have anything to do with these guys after all?

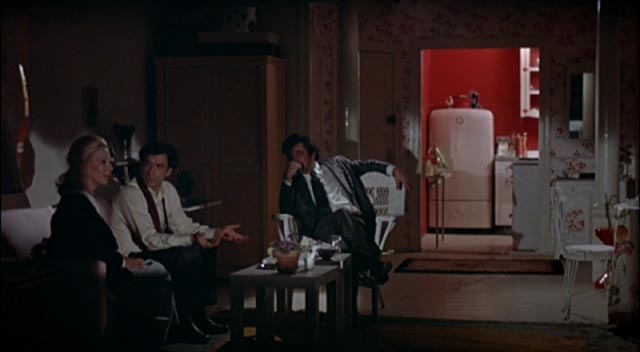

The film’s toughest, most uncomfortable scene is a lengthy visit to Nicky’s girlfriend Nellie (Carol Grace). Insecure, beaten down by life and men, she wants reassurance and affection, while Nicky wants submission and physical gratification. His attempt to force himself on her is made even more unpleasant by the presence of Mikey, sitting across the room; and it just gets worse when Nicky urges Mikey to have a go himself; he asserts his own power by casting Nellie as a prostitute available to anyone (and has apparently in the past sent other friends to her in an effort to prove the truth of his contemptuous view of her). As an illustration of insecure men using a vulnerable woman to reassure themselves and reinforce their own emotional bonds, this scene is as brutal as any overt violence.

A subsequent scene in which Nicky visits his estranged wife, who recently left him with their baby, sheds light on that brutality. Jan (Joyce Van Patten) has found the strength to disconnect from him, rejects him and the life he leads and doesn’t care that he’s got himself into possibly fatal trouble. As physically intimidating as Nicky is, she stands her ground, refusing to bolster his fragmenting sense of himself as a tough guy.

Mikey’s relationship with his wife is very different, at least on the surface. They live in a nice home in a nice neighbourhood with nice furniture. He makes several phone calls to her during the night, seemingly considerate (until we realize that he is using her to pass messages to Kinney). But when he returns at dawn, having lost Nicky, all the trappings of security are exposed as props holding up an image which doesn’t truly reflect his reality. Annie (Rose Arrick) doesn’t know the real him, the Mikey whom Nicky knows and has known since childhood. Nicky is closer to him than his own wife and kid and yet through this night he has been working towards a devastating betrayal which is finally realized right on his own doorstep. The ending of Mikey and Nicky is one of the most powerful expressions of hopelessness and despair offered at a time when the New American Cinema was steeped in downer endings – from The Wild Bunch and Bonnie and Clyde, through Mean Streets and Night Moves – but once again May avoids romanticizing and mythologizing. This is a moment of irredeemable personal horror and emotional pain, not some lofty existential statement.

It’s perhaps no wonder then that a major studio didn’t know what to do with the film and that it was destined to take a long time to find an appreciative audience. The film’s restoration and subsequent Blu-ray release by Criterion should finally bring it recognition as the masterpiece of a genuinely original filmmaker whose career was sadly truncated by her insistence on being true to her own vision (something often admired in men but resented in women). And who knows, perhaps it may even lead to a re-evaluation of Ishtar …

*

The disk

Shot for the most part by Victor J. Kemper (the end sequence is credited to Lucien Ballard), Mikey and Nicky has a very raw visual style. Filming mostly at night on the streets of Philadelphia, it appears to have used mostly available light. It’s a dark film, with a lot of grain, giving it a documentary-like immediacy which heightens the improvisatory feel of the story (which was, in fact, mostly scripted by May; the spontaneity of the performances is a tribute to Cassavetes’ and Falk’s total immersion in their roles). While May was obviously concentrating on the actors, the seeming artlessness of the visuals is deceptive; the camera is vividly attentive to location and the physical expressiveness of the performances – there are many wordless moments which convey depth and complexity of feeling through the intimate interaction of actors with camera.

The sound is also quite raw; it’s obvious that little if anything was looped to smooth over inconsistencies in location recording, sacrificing technical polish to maintain the authenticity of the moment.

The supplements

There are two featurettes on the disk, the first giving an account of the production through interviews with cast-member Joyce Van Patten and distributor Julian Schlossberg (14:39), the second with critics Richard Brody and Carrie Rickey evaluating the film and its relationship with May’s other work (23:20).

In addition there’s a contemporary radio interview with Falk conducted by Schlossberg in 1976 (45:09) in which the actor provides valuable insights into the world being depicted in the film and gives a detailed backstory for the characters.

What’s sorely missing is any input from May herself.

A trailer (1:38) and TV spot (:32) emphasize the gangster milieu, but naturally don’t convey the film’s commercially problematic originality.

Critic Nathan Rabin provides an excellent essay for the booklet.

Comments

SANFORD Meisner, not “Stanford.”

I stand corrected for my typo.