Italian cops and killers

Italian commercial cinema has passed through many distinct waves, often flaring up and burning out in a matter of years. Although international awareness rose after World War Two with the revelatory flowering of Neorealism – Roberto Rossellini’s War Trilogy, Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves, Umberto D. and others, Luchino Visconti’s La Terra Trema – and gained momentum with Federico Fellini, Michelangelo Antonioni, Bernardo Bertolucci, this “art film” stream was not necessarily all that popular at home. Italian audiences preferred various genres which took much longer to gain outside popularity – largely as a result of availability on home video in Britain and the U.S. from the late 1970s on. Some genres, like homegrown comedies, never did travel well, but others – often inspired by or derived from foreign successes – redefined familiar genres and gained increasing commercial success with English-speaking audiences.

In the late 1950s, the popularity of Hammer films inspired Italian Gothic horrors; by the mid-’60s, spaghetti westerns flourished, while horror mutated in the wake of Psycho into what would eventually gel as the giallo; and after the international success of The French Connection and Dirty Harry in 1971, the giallo at its height was challenged, and eventually overtaken, by poliziotteschi, a strain of violent thrillers packed with morally ambiguous cops and criminals, which reflected Italian national social and political upheavals. In the ’70s, with the rise of domestic terrorism and the overt political power of organized crime in parts of the country, an atmosphere of paranoia and violence was ripe for exploitation. Nihilism turned out to be profitable.

In some ways, despite formulaic elements, poliziotteschi were more versatile than the giallo because the genre was more clearly rooted in the real world rather than a fever-dream construct of fantastic psychological extremes. While cops were often peripheral in the giallo, they were frequently central to poliziotteschi – but not as symbols of order holding chaos at bay; more often then not, they were like Harry Callahan and Popeye Doyle, loners who have to fight against the bureaucratic restraints imposed by their superiors and take on the methods of the criminals they were fighting in order to obtain some kind of rough justice.

When the cops held a more traditional position, the focus of the genre would shift to the criminals, finding more interest in their psychopathology than in the mechanics of detection and mystery-solving. Three recent disks lean in this direction – two suffused with moral ambiguity and the third descending into the mire with its savage “hero”.

Almost Human (Umberto Lenzi, 1974)

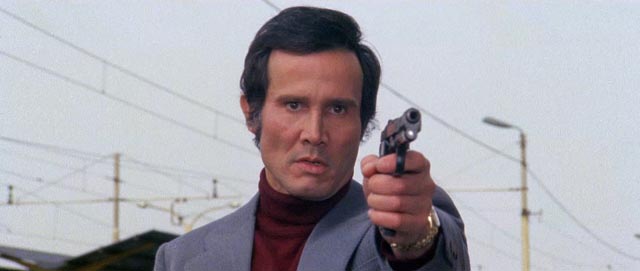

The latter is the best movie I’ve ever seen by Umberto Lenzi, whose other work is often brutally artless (Nightmare City [1980] is one of the crudest Italian zombie movies, while Eaten Alive [1980] and Cannibal Ferox [1981] tried to push the offensiveness of Ruggero Deodato’s Cannibal Holocaust [1980], but completely lacked Deodato’s conceptual sophistication). Lenzi made several routine gialli, complete with the requisite narrative incoherence, but I honestly can’t remember much about the ones I’ve seen (Seven Blood-Stained Orchids, Spasmo). Almost Human (1974, on-screen title on the Code Red Blu-ray The Executioner) is something else again. With an excellent script by the prolific Ernesto Gastaldi and a brutally intense lead performance by Cuban-born Actors Studio alum Tomas Milian, already a familiar face from numerous spaghetti westerns and gialli, this movie is crime melodrama as horror film.

Milian tears into the role of petty criminal, full-blown sociopath Giullio Sacchi with so much energy that he lifts the entire film out of genre routine. In the opening scene, waiting behind the wheel of a getaway car outside a bank, he panics when a traffic cop approaches to tell him he can’t park there. He shoots the cop, drawing immediate attention to the robbery. He insists he had no choice, but the gang beat him up for risking the whole job. Two things are quickly apparent: Giullio is not a reliable gang member, and he’s violent because he rather likes it.

Looking to become more important, he decides to make a big score by kidnapping the daughter of his girlfriend’s industrialist boss. He recruits a couple of compliant guys to help and proceeds to wreak havoc because, for one thing, he’s not very smart, and for another his all-purpose method for dealing with obstacles – which eventually include his girlfriend, his co-kidnappers, and the kidnapped girl herself – is to dispose of them violently. He’s an agent of chaos, the crime itself merely being an excuse for expressing his compulsion for violence. (The original U.S. title, Almost Human, is far more apt than the one on this particular print.)

The casting of Henry Silva as Commissario Walter Grandi, the cop following Giullio’s bloody trail, provides an effective counterbalance to his uncontrolled savagery, although Grandi is always just too late on the scene to prevent the slaughter. Giullio himself is a more plausible and frightening monster than any of the overt horrors in Lenzi’s other movies; Almost Human is the director’s nihilistic masterpiece.

Strangely, the Code Red Blu-ray I obtained from Screen Archives contains only the English-dubbed version titled The Executioner, plus a 29-minute interview with director Lenzi – while all the on-line reviews cite two different cuts (the one on my disk, plus an alternate, slightly longer U.S. cut from a lower-quality source), both English and Italian tracks, an interview with Milian and a lengthy featurette featuring Lenzi, Milian, co-star Ray Lovelock and writer Gastaldi. I haven’t found any explanation for the stripped-down version I received.

*

in Vittorio Salerno’s No, the Case is Happily Resolved (1973)

No, the Case is Happily Resolved (Vittorio Salerno, 1973)

I’d never come across Vittorio Salerno until I acquired this disk. He only directed four features between 1965 and 1981 (three written or co-written by Ernesto Gastaldi, who also co-directed the first, Libido [1965]). From on-line descriptions there appears to be no distinct pattern or focus for his directorial work – a psych0sexual thriller, a movie about young professionals who turn to crime for kicks, a supernatural horror. The disk in question here – the only one made without Gastaldi’s participation (it was co-written with Salerno by Augusto Finocchi, who seems to have specialized in spaghetti westerns, though he was also one of the writers on Jess Franco’s Count Dracula [1070]) – was Salerno’s solo directing debut and it’s an original and disturbing thriller.

I came to this oddly titled movie, No, it caso e felicemente risolto (No, the Case is Happily Resolved, 1973) by accident. It showed up in a newsletter email from Diabolik DVD, but when I looked it up on the Diabolik site I couldn’t find it. So I emailed them and was told it had been listed in error and the Blu-ray had gone out of print. That, of course, just sweetened the bait, so I kept searching and finally found a copy (a bit expensive) on eBay and ordered it, although I still didn’t know much about the movie beyond a general plot outline.

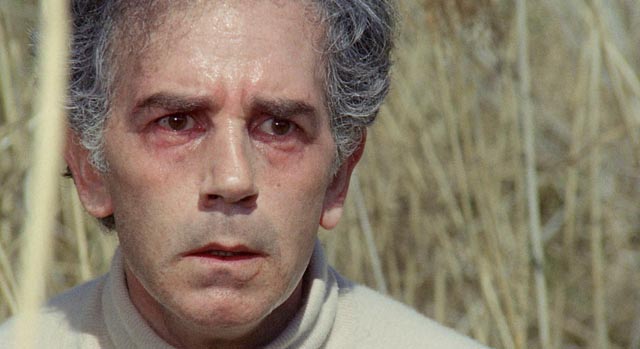

The film is structured something like a Hitchcock thriller. Out for a quiet day of fishing at a picturesque rural location, Fabio Santamaria (Enzo Cerusico) witnesses a brutal murder across the water. Drawn by screams, he sees a man bludgeoning a woman to death. Startled and fearful, he freezes and the killer notices him watching. They lock eyes for a moment, then he turns and runs. All that follows derives from Fabio’s moral cowardice. He considers going to the police, but then decides that his life would be upended by getting involved. Haunted by what he saw, he nonetheless just goes back to his life without telling anyone.

But then he suddenly finds himself being sought by the police, suspected of the murder. The killer, a respected teacher named Professor Eduardo Ranieri (Riccardo Cucciolla, driver of the hijacked car in Mario Bava’s Rabid Dogs [1974]), had noted the license plate on Fabio’s car as he drove away and himself went to the police to report having seen Fabio killing the woman. Even turning himself in to tell his story can’t deflect suspicion; Fabio’s initial failure to do the right thing has set him on a disastrous course and Salerno follows the consequences to their inevitable conclusion.

Fabio’s moral weakness is compounded by entrenched class attitudes; although Fabio is a perfectly normal lower middle class man, the Professor’s status as a respected professional, a self-assured, well-dressed member of a higher social class, gives him far more credibility than Fabio, whose shiftiness is inevitably interpreted as unreliability and probably guilt. The police and legal establishment lean towards trust in the Professor without any apparent awareness of their own underlying prejudices. Only a newspaper editor who distrusts the obvious sees through Ranieri’s facade of respectability.

With superb performances from the entire cast – which includes the director’s brother Enrico Maria Salerno as the newspaperman and Martine Brochard as Fabio’s wife – excellent photography by Marcello Masciocchi and a fine score by Riz Ortolani, No, it caso e felicemente risolto comes closer in execution to the social critique of Elio Petri’s Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (1970) than to Hitchcock’s “wrong man” thrillers. It’s a remarkably assured first feature and deserves to be much better known.

Camera Obscura’s region B Blu-ray features a beautiful HD transfer from what appears to be a flawless source, with Italian and German audio tracks. This German company specializes in Italian genre movies and this disk shows the same care they apply to all their releases, from the excellent technical specs to some informative extras – here a commentary from film historians Martin Stiglegger and Kai Naumann (in German with English subtitles) and a forty-minute documentary about the film featuring director Salerno and co-star Martine Brochard.

*

Corrupt (aka Copkiller aka Order of Death,

Roberto Faenza, 1983)

I saw Roberto Faenza’s movie on its original theatrical release back in the early 1980s. Here in Canada it was called Copkiller (a literal translation of the original Italian title, L’assassino dei poliziotti); in the U.S. it was released as Order of Death (a somewhat meaningless title, which is nonetheless the title of the source novel), and later reissued as Corrupt. Code Red’s Blu-ray is packaged as Corrupt, but the on-screen title is Order of Death. This kind of title confusion usually signifies a ragged release history, and the film did pretty much disappear for a couple of decades. When I first saw it, I didn’t know anything about Faenza – a controversial figure who studied both political science and cinema, his film work was apparently deeply inflected with political concerns; he won a number of awards as well as having films banned and criticized from both the Left and Right.

Political controversy made it difficult for him to find funding in Italy in the early ’80s and he went to the U.S. for Copkiller – partially financed by an Italian cooperative and RAI, with input from American distributor New Line. Based on a novel by British painter and writer Hugh Fleetwood (who lived for years in Italy), and adapted by Fleetwood in collaboration with Faenza and the eclectic Ennio De Concini (Sergio Leone’s The Colossus of Rhodes, Mario Bava’s The Girl Who Knew Too Much, Mikhail Kalatozov’s The Red Tent, Lucio Fulci’s The Four of the Apocalypse, Tinto Brass’ Salon Kitty, Monte Hellman’s China 9, Liberty 37, Marco Bellocchio’s Devil in the Flesh), Copkiller has an odd and distinctive flavour. Set in New York, with location exteriors shot in the city, the predominant interiors were shot at Cinecitta in Rome, giving it a stateless atmosphere amplified by a cast of American, English and Italian actors. This mix of ingredients is compounded by the script’s psychological and moral ambiguities.

If Salerno’s film is a taut thriller about an ordinary man derailed by circumstances complicated by his own personal weaknesses, Faenza’s movie is a cooler, more intellectual affair. It begins with a deceptive title sequence which seems to signal a typical piece of ’80s exploitation (something by William Lustig, say): a man drives into a bit of garbage-strewn waste ground by a river across which we can see the New York skyline. He takes a gun, a police shield and what looks like a small baggie of drugs from the glove box and starts walking past a mound of trash. We glimpse someone in a ski mask crouched behind the garbage bags, a box cutter in his hand. He jumps the cop, pushes him to the ground, slashes his throat and leaves him lying there in a spreading pool of blood.

There’s a killer stalking the city, his chosen victims apparently crooked cops. We quickly discover that our protagonist is exactly that. Lt. Fred O’Connor (Harvey Keitel) is a city detective who, along with his partner Bob Carvo (Leonard Mann), has invested his graft in a large apartment facing Central Park. He retreats here after work to relax, sitting in a chair facing the view, listening to the stereo. The apartment contains no other furniture. It’s an investment, a stark symbol of wealth which serves no purpose other than the having of it. O’Connor seems content with this, but Carvo is beginning to be plagued by his conscience. He wants out. He wants to sell the place and use the money to disappear, but O’Connor has no interest in changing the status quo.

Then one day a twitchy young man enters O’Connor’s life, revealing that he has been observing the cop for months, that he knows all about his criminal activities. And this guy, Leo Smith, claims to be the cop killer. O’Connor doesn’t believe him – he’s a small, skinny runt, surely not capable of overpowering trained policemen. He’s also what makes the film interesting as a cultural artifact beyond its intrinsic values as a thriller because he’s played by none other than John Lydon, better known as The Sex Pistols lead singer Johnny Rotten. Lydon may not have particularly refined acting talents, but he’s a riveting screen presence who easily holds his own against the as-ever intense Keitel. The pair develop a sadomasochistic symbiosis which overturns O’Connor’s complacent equilibrium.

O’Connor imprisons Leo in the apartment, hand-cuffing him in the bathtub while he tries to figure out whether he is actually the cop killer and, perhaps more importantly, what to do with him. Turning Leo in would expose O’Connor’s own corruption. It all goes from bad to worse when Corvo discovers the prisoner and tries to free him. O’Connor more or less accidentally kills his partner and then decides to make use of Leo to cover it up by setting him up as the killer … after all Leo does claim to be the cop killer.

We never clearly learn whether Leo is a genuine psychopath or just a troubled guy who confesses in order to gain attention, but his entry into O’Connor’s life peels back the protective layers the cop has wrapped around himself to mitigate his corruption. Leo reveals O’Connor to himself and in so doing exposes what a genuine monster he is.

In the ten years since his breakthrough in Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets (1973), Keitel had created a powerful screen presence in a variety of roles, often as a twitchy character perpetually on the brink of exploding into violence. He makes good use of that image here, engaging the viewer in a kind of conflicted identification with the cornered cop, our sympathies gradually being eroded as our doubts about Leo’s own guilt grow. This playing with audience identification makes Copkiller an uncomfortable film, implicating the viewer in its escalating pathology – which may explain why it has had such a low profile for three-and-a-half decades despite the presence of Keitel.

Code Red’s Blu-ray features a new HD scan from an original interpositive of the U.S. cut of the film (the Italian cut apparently runs about twelve minutes longer). The look adds to the downer atmosphere, with drab colours leaning towards blue and green, but the image is quite clean and holds a decent level of grain. The only extra is a nineteen-minute interview with co-star Mann, who mostly talks about his career rather than this film in particular. The disk does a decent job of resurrecting the film, but it would have been nice if Code Red had gone the extra distance and provided both cuts – and maybe an interview or commentary with Faenza and/or writer Fleetwood, who apparently are both still alive. The real icing would be some participation by Lydon … but that will no doubt have to remain my fantasy version of the disk.

Comments