Race, class and crime in New York

in Sidney Lumet’s The Anderson Tapes (1971)

One of the pleasures to be had from old movies – one unrelated to the narrative content, sometimes unrelated to the actual cinematic qualities of any individual film – is the peripheral documentary element provided by location shooting. Mainstream movie-making was largely studio-bound until after World War Two, partly because equipment was too large and cumbersome to be easily managed outside of a controlled environment, and partly because it was financially more feasible to shoot on soundstages and backlots. Even outdoor adventures and westerns were frequently shot on studio-owned ranches, with occasional exceptions like John Ford’s Stagecoach (1929), parts of which were shot in the barren landscapes of Utah and Arizona. The war itself helped to change this. Combat photographers filmed with smaller, more portable cameras which proved that it wasn’t necessary to use big studio cameras to get effective results. In addition, what those photographers filmed accustomed audiences to the visual power of real places, something which would be amplified in the years right after the war when North American audiences got their first taste of Italian neorealism.

Location shooting was an important factor in decisively separating cinema from theatre. Actors playing their roles in real places demanded a different style of performance, one which evoked at least the illusion of naturalism. But what makes these “real world” settings fascinating now is the record they provide of what the world looked like back then. When I watch old movies which were shot on location, I often find myself paying more attention to the glimpses of the streets behind the actors than to the story being played in the foreground. This is an aspect of film which hearkens back to the earliest days of cinema and “actualities” – photographic records of a place or event which existed purely for their own sake: workers leaving the Lumiere factory, a train pulling into a station – the transformation of our lived-in world into an aesthetic artifact which can be revisited even as the actual world changes and moves on.

The most potent type of location footage is that shot on city streets because these are the places most subject to rapid, incessant change. Not just the buildings – some of which remain for decades with only superficial changes – but the social and economic veneer which clings to the surfaces of those buildings; store signs, theatre marquees, commercial purposes which are in constant flux as fortunes rise and fall. Times Square in the ’40s is very different from Times Square in the ’70s which is very different from Times Square in the ’00s. Being deeply obsessed with movies as I am, I particularly try to decipher theatre marquees as they flash past the windows of cars driving down busy avenues. A familiar title can give me a momentary (illusory) connection with the dramatic world of the movie I’m watching.

Purely by chance, I’ve recently watched two movies shot in New York at the beginning of the 1970s. They use location in different ways and, in effect, portray very different cities, but both were shot in part out on the streets where the place imposes itself to some degree on the filmmakers. One, with a bigger budget and a highly respected filmmaker, seems controlled and contained – the city used as set – while the other, with a low budget and a first-time director, seems ragged and raw and to a degree more “real”. But both centre on outsider characters, criminals at war with a seemingly impenetrable society of unattainable privilege.

*

The Anderson Tapes (Sidney Lumet, 1971)

Sidney Lumet had a highly productive career in television drama throughout the 1950s, only gradually working his way into feature films over the five years between 1957 (his theatrical adaptation of Reginald Rose’s live TV play 12 Angry Men [1954]) and 1962’s Arthur Miller adaptation A View From the Bridge, after which he exclusively made movies. With a passionate interest in character and storytelling, Lumet was prolific but never emerged as an auteur in the sense of a filmmaker with overriding thematic and stylistic concerns; he adapted his approach to the material at hand (many adaptations of plays and novels) and at his best created intense, layered stories about characters in crisis. Although he did repeatedly make excursions elsewhere, he remained a New York director, always returning to the city where he felt most comfortable.

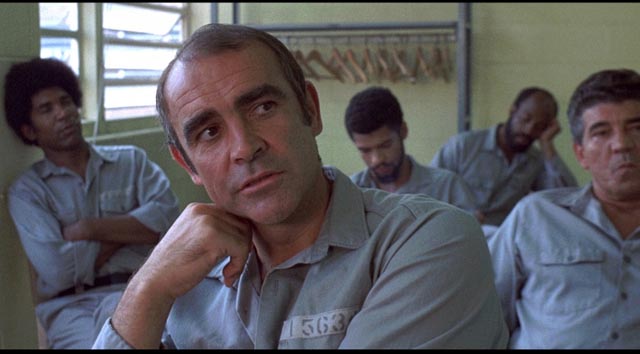

The Anderson Tapes (1971), the second of five films Lumet made with star Sean Connery[1], is a caper movie adapted from Lawrence Sanders’ first novel, which used a then-fresh gimmick to tell its story. As the title indicates, the book consists of a collection of transcripts and documents compiled from multiple police and intelligence sources, all of which inadvertently catch glimpses of an elaborate robbery planned by recently released ex-con Duke Anderson. Written a few years before Watergate exploded with revelations of Nixon’s secret White House tapes, the book portrays a society under constant surveillance, both legal and illegal – an idea which seems a bit “duh” now, but at the time was disturbingly suggestive of major social and political changes.

The tapes in question are audio recordings of meetings between various criminal figures who are being watched by law enforcement agencies and private investigators. Duke is an unknown figure who pops up in various meetings as he tries to get backing for the big job he has planned. It’s only in retrospect that his significance becomes apparent to the observers. This device, although it’s still woven through Frank Pierson’s script, remains a sometimes awkwardly grafted on element rather than an essential story key. What might have been the grandfather of found-footage movies is essentially a conventional narrative with all this spying tossed in for occasional satirical purposes. The surveillance seldom has any impact on the action itself.

The most interesting aspects of the movie are the cast – Connery as the bitter, ambitious Anderson; a young Christopher Walken, Martin Balsam, Dick Williams and Stan Gottlieb as his crew; Alan King as the mob boss who finances the job; Dyan Cannon as Anderson’s girlfriend – and the upscale New York location – primarily an apartment building on East 91st Street (used for exteriors, though the interiors were built on a soundstage in Manhattan) and the surrounding streets. This building is a symbol of wealth and privilege and Anderson is determined to strip it of everything of value.

In the film’s opening scene (caught on tape by a prison psychiatrist during a group therapy session), Anderson expresses his philosophy in what are now uncomfortable terms. For him blowing open and emptying a safe are a form of rape – he confesses that he’d get sexually aroused on a job. He also goes on a rant about how what he does is just a retail version of what the rich establishment does wholesale – exploit and steal from those below them on the social scale. His crimes are a form of punching up, taking back what the wealthy have stolen from everyone else. Although there’s an incipient class critique in this, it comes across as little more than self-justification and the inhabitants of the target building for the most part don’t seem like predatory autocrats.

From a visual standpoint, Lumet’s use of the city in this film lacks the layered texture of films like Serpico (1973) and Dog Day Afternoon (1975), which seem so much more lived-in. The city here feels strangely empty – the gang drive down wide streets virtually devoid of traffic and pedestrians. It’s almost a conceptual landscape in which the idea of wealth has supplanted actual living people except for those cocooned with their possessions inside the building.

*

Super Fly (Gordon Parks Jr., 1972)

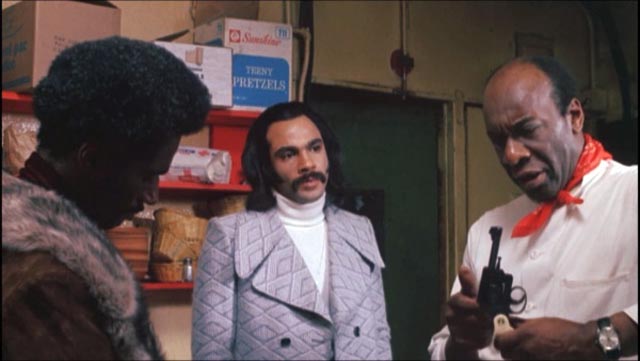

Super Fly (1972), the debut feature of Gordon Parks Jr. (made just a year after his father’s breakthrough feature, Shaft), might as well take place on a different planet, not just across town from The Anderson Tapes. Without Lumet’s resources, Parks shoots much of the movie guerrilla-style on streets inhabited by ordinary people going about their business, following his characters past grungy storefronts, into garbage-strewn alleys, across empty lots clogged with piles of rubble, into smoky nightclubs and rooms decorated with eye-searingly garish ’70s style which complements the outrageous fashion sense of the people who inhabit them. If Lumet’s New York in The Anderson Tapes feels like a vast studio construct erected for his film, Parks’ New York is an observed existing urban space which gives a degree of authenticity to the figures who populate it. In Lumet’s film, we’re very much aware of actors skillfully portraying fictional characters; in Parks’ film, with less familiar performers, we seem to be observing people who naturally inhabit this damaged social space.

Super Fly, written by Phillip Fenty (the first of only two feature credits), is the story of Priest (Ron O’Neal), a drug dealer and part-time pimp in Harlem, and his efforts to make a big score that will enable him to escape the life which has been forced on him by a racist society. He’s smart and articulate, but the only opportunities open to him are the criminal ones he’s taken advantage of to give himself a comfortable but constrained life. He wears big, loud clothes, drives a big tricked-out car, has a Black girlfriend, Georgia (Sheila Frazier), he’s not particularly committed to and a middle class white mistress, Cynthia (Polly Niles), who likes the danger he represents and the drugs he can supply to her white friends.

With his partner Eddie (Carl Lee, son of actor Canada Lee), Priest seeks the help of his mentor Scatter (Julius Harris) in making a connection with a wholesale cocaine supplier; he wants to get hold of enough of the drug to make a quick million-dollar profit – money being the only way to escape his current life. Scatter is bitter, having tried to escape that life himself (he now owns a small club and wants to avoid crime) and Eddie has no ambitions to escape, just wants to keep making money.

In Lumet’s movie, white privilege is protected by a police force which serves the moneyed class (as the cops prepare their assault on the building, Captain Delaney [Ralph Meeker] cautions his men that their primary job is to “protect private property”); in Parks’ film, the cops are corrupt, keeping people like Priest trapped in their criminal lives in order to exploit them, skimming a big share of the profits. But Priest is smarter than the Man. He arranges his deal, and buys himself protection from the cops – as he tells the corrupt Deputy Commissioner (producer Sig Shore) at the climactic moment, he has paid a large sum to dependable (that is, white) killers who will go after the Deputy Commissioner and his family if anything happens to Priest. He uses the system’s own corruption against it, seizing what power is available to him within that system.

While blaxploitation eventually devolved into violent action movies and a degree of self-parody, Super Fly is built around a critique of the ways in which race shapes American society. Priest understands how that society works – and works against him – and uses what he knows to bend it to his own will. The film has a rough street-level energy which is greatly aided by the screen presence of Ron O’Neal, a classically trained actor in his first leading film role; he has intelligence and authority which by its mere presence serves as a pointed criticism of American society and its refusal to create space for Black people (in this, it parallels Duane Jones’ performance in Bill Gunn’s Ganja & Hess [1973]). O’Neal elevates this gritty crime story the way William Marshall elevated the impoverished horror cliches of William Crain’s Blacula, made the same year. If blaxploitation was eventually co-opted by the mainstream movie business as a way to make money off a particular audience, in these first few years a variety of filmmakers seized various genres and turned them into a pointed attack on the status quo – Melvin Van Peebles with Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971), Bill Gunn with Ganja & Hess, even Shaft (1971), in which Parks’ father aggressively claimed the familiar private eye genre for a dynamic Black star – and Super Fly is a key title in this movement.

America has traditionally tried to deny issues of class – the national myth is that anyone can make it if only they work hard enough – but it remains there as a constant shadow. Class resentments drive Duke Anderson as he schemes to take what those who are better off than him possess. His plans are carried out on the home ground of the privileged. Priest has no direct access to that world, but is trapped in another part of the city where class is manifest as a specifically racial divide. The privilege Duke aspires to is built on the dispossession of the people Priest lives among. The two films together, with their widely different views of New York City, caught at one particular time, throw that division into stark relief.

*

As crucial to Super Fly’s worldview as O’Neal’s performance is Curtis Mayfield’s score, which providess a rich layer of socially and politically-conscious commentary over the narrative, at times almost like a Greek chorus addressing and interpreting the story’s characters and events.

Interestingly, Lumet’s film was scored by another legendary Black composer/musician, Quincy Jones. Jones’ score is continually punctuated (and punctured) by electronic squeaks and blips signifying the ever-present surveillance technology. This gives the film a hint of science-fictional futurism, echoing the soundtracks of Joseph Sargent’s Colossus: The Forbin Project (1970, scored by Michel Colombier) and Robert Wise’s The Andromeda Strain (1971, scored by Gil Mellé).

*

Both films get strong hi-def transfers on Blu-ray, The Anderson Tapes in a dual-format edition from Indicator, Super Fly from Warner Archive. The former has a commentary from critic Glenn Kenny, which situates the film in Lumet’s body of work and relates it to the source novel. Super Fly has an enthusiastic commentary from academic and film historian Dr. Todd Boyd, who lays out its significance as both a piece of skillful filmmaking and a work of cultural importance.

There are several short featurettes on the Super Fly disk, with Curtis Mayfield, Ron O’Neal, costume designer Nate Adams, and Les Dunham, who created Priest’s car, reminiscing about their work on the project, plus a 24-minute retrospective making-of.

The only other extras on the Lumet disk are a 16-minute super-8 home movie version, a trailer and an image gallery, plus the company’s usual informative booklet.

_______________________________________________________________

(1.) The Hill (1965), one of my favourite Lumet films; The Anderson Tapes (1971); The Offence (1973); Murder on the Orient Express (1974); Family Business (1989). (return)

Comments

I know I went to see The Anderson Tapes in the theater when it came out in Winnipeg. I don’t remember seeing it when VHS came along and I know I haven’t seen it since. I’m not a big fan of Sidney Lumet. I can’t say I’ve seen much of his work, I’ve seen a lot of films from the 70s but by the 80s he wasn’t anyone I was paying attention to. I only have one of his movies, the 1974 Murder On The Orient Express and only because it’s an Agatha Christie adaptation. I collect those. Just ordered a couple more today. Doubt I’ll get to seeing The Anderson Tapes again anytime soon but you never know. Tell you the truth I’d rather watch Superfly over. Actually, I have and fairly recently. Not the Blu-ray. I watched a copy from Netflix just. I don’t think I need to own a copy but who knows it might be on clearance one day.

Looking over his filmography, I have to admit there are only a handful of films I’d readily watch again. I really like The Hill; Fail-Safe is clunky, but I’m a sucker for doomsday stories; The Deadly Affair and The Offence are worth a look. His best work is probably his New York “trilogy” – Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon and Prince of the City. I re-watched Serpico recently and was reminded just how good it is, probably his best film overall. Network is ridiculously overrated. And I’m embarrassed to say I’ve never actually seen The Pawnbroker.

I don’t know if The Pawnbroker is good cinema, but I was very affected by it. I saw it over 20 years ago, and I’m not sure I’m ever going to be ready to see it again.

Now I feel that I definitely have to track it down.