Agnès Varda 1928-2019

Sad news … Agnès Varda died yesterday, March 29, in Paris. She was working right up to the end, with what turned out to be her final film released in France just eleven days earlier. Varda by Agnès continues her documentary examination of her own life and career, the central focus of her work since 2000’s The Gleaners & I, continuing through The Beaches of Agnès (2008), the five-part television series Agnès Varda: From Here to There (2011) and Faces Places (2017). Beginning with her debut feature La Pointe Courte in 1955, her films – fiction and documentary – reveal a fascination with life which embraces personal experience and the social, political and artistic forces which shape the world we live in.

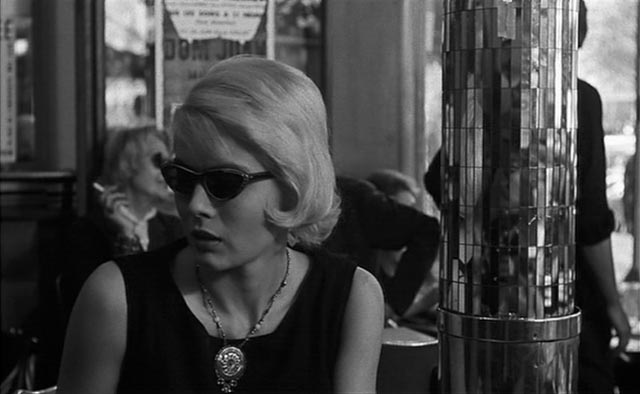

And yet despite her range and her often innovative approach to filmmaking, she remained something of an outsider in French cinema until the international success of Vagabond (1985) and the late career flourish which began with Gleaners. This enigma is even more puzzling given that her work was so important to the Nouvelle Vague – that first feature, La Pointe Courte, paved the way even as it bridged the gap between the soon-to-be movement and its roots in Neorealism. Her first masterpiece, Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962), is a work of great psychological depth and emotional power, while also being a rich portrait of Paris at the time, devoid of the egotistical cleverness which marks Godard’s Breathless, while Le Bonheur (1965) is at least as complex in its treatment of narrative as anything Godard was doing in the same period.

Varda preferred to work with lesser-known actors or non-professionals, and after what she considered the failure of The Creatures (1966), which starred Catherine Deneuve, she concentrated almost exclusively on documentaries for the next decade and continued making documentaries and essay films for the rest of her career even as she resumed dramatic filmmaking with her feminist feature One Sings, the Other Doesn’t in 1977.

My first encounter with Varda’s work was seeing Vagabond in the mid-’80s at Winnipeg’s long-vanished repertory arthouse theatre Cinema 3. It seemed an almost overwhelmingly bleak film, an unsparing portrait of a young, discarded woman for whom society had no use. It began with the woman’s death, casting a pall over every moment of the life we then see in flashback. Starting there, it came as a shock to encounter the warmth of Cleo a few years later (on video), a film about another woman whose place in society seems uncertain as she wanders the streets of Paris awaiting the results of a cancer test. Although the possibility of sickness and death hangs over Cleo from 5 to 7, the earlier film is about the gaining of self-awareness and eventually embracing life.

It is that attitude which informs everything Varda did in her self-examination from Gleaners on. We not only see her growing older and in some ways more frail (in Faces Places she is losing her eyesight), we observe her own fascination with the physical effects of her own aging. One of the most resonant moments in Gleaners comes as she trains her small video camera on her own hand, in awe of the landscape described by flesh and bone which is attached to her own body. She embraced the process of aging even as she spent more time looking back over her life and the work which which grew out of it, seemingly surprised and delighted and moved by what she had experienced and achieved.

I haven’t yet seen her last film, so the final image I hold is from the end of Faces Places, a moment which seems to point back to her exclusion from the testosterone-fueled Nouvelle Vague dominated by Godard and Truffaut, Malle and Chabrol; she takes her companion, photographer JR, to meet the legendary Godard at the filmmaker’s house only to find no one there to greet them despite the visit having been previously arranged. Whatever Godard’s reasons for not being there, his absence can be read as a slight … and Varda seems visibly upset by what looks like a snub. A filmmaker with remarkable range and depth, one whose work displays a fascination with both human behaviour and the formal possibilities of cinema, who gained more familiarity and respect as she worked through her eighth and ninth decades, Varda had somehow remained outside the club which drew inspiration from her early work yet never quite accepted her as a member.

*

News of Agnès Varda’s death brought back memories of my own close encounter with her nine years ago. I was working briefly in Paris (as assistant editor on the Milla Jovovich feature Faces in the Crowd), when a friend decided to visit for ten days as I had an apartment and could offer her a place to stay. My friend adored Varda and her work and really hoped to meet the filmmaker, but there were scheduling issues. It turned out that Varda would be leaving Paris the same day my friend arrived … timing was terribly tight. So at my friend’s insistence, I phoned the office of Varda’s production company, Ciné Tamaris, to see if there might be any possibility of a brief meeting.

The phone was answered by a woman who responded to my questions rather brusquely. Although she spoke English, I wasn’t sure she actually understood what I was talking about. But soon after the end of our inconclusive conversation, I got a call back and this same woman was friendlier and more helpful. It became obvious that there was no way to make a connection – Varda would be gone before my friend would be able to get into the city from the airport. It was only at the end of this second conversation that it dawned on me that I was actually talking to Varda herself. Although it didn’t work out, I was charmed by the fact that Agnès Varda, 81-years-old and busy with the details of her upcoming trip, had shown an interest in a complete stranger who was coming from Canada and really wanted to meet her, and had taken the time to call me back and try to find some way to accommodate my friend.

Comments