More late winter viewing, part one

Despite my recent qualms about the value of much of what I’m watching these days, I offer yet more short notes about movies at least some of which someone with more discerning taste might well have skipped. Here I start with some older titles, to be followed in a subsequent post by more recent movies.

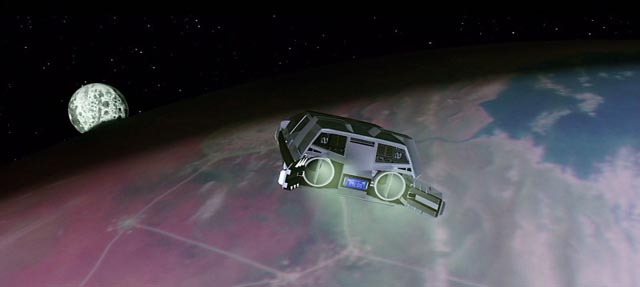

The Green Slime (Kinji Fukasaku, 1968)

Kinji Fukasaku is one of my favourite Japanese directors, a filmmaker capable of remarkable work who also banged out a lot of disposable entertainment during a long career. It took quite a while before he began to be taken seriously in the West, perhaps partly because the first of his movies to get wide distribution in English-speaking markets were silly sci-fi efforts – The Green Slime (1968) and Message from Space (1978). And yet in between those two, he produced, at a furious pace, some of the most powerful and insightful Japanese genre movies of the period – the Battles Without Honour and Humanity series (1973-74) and its “sequel”, New Battles Without Honour and Humanity (1974-76), as well as Under the Flag of the Rising Sun (1972), a searing drama examining the treatment of ordinary soldiers by the Japanese military towards the end of the war. At the end of his long career, he demonstrated his range and depth by completing two of his finest films: The Geisha House (1998) and Battle Royale (2000), the latter, remarkably, made at the age of seventy.

Within this body of work, The Green Slime might seem like an embarrassment. It was an international production, co-financed by MGM and Toei Studios, using a largely American cast and Japanese technical resources. The effects and model work are sub-par even when compared with Toho’s lesser Kaiju movies of the late 1960s and ’70s … in fact, even when compared with the Gerry and Sylvia Anderson puppet shows being made around the same time (Thunderbirds, Captain Scarlet). And yet The Green Slime is ridiculously entertaining. But before it gets to the crazy monster action, there’s some perfunctory character drama – a romantic triangle between Commander Jack Rankin (Robert Horton), assigned to save the Earth by destroying an approaching asteroid (he has less than twenty-four hours to do the job – much less time than Bruce Willis and his drilling crew in Michael Bay’s Armageddon [1998]); Commander Vince Elliott (Richard Jaeckel) of Space Station Gamma 1, still bitter about Rankin giving him a bad report for having sacrificed ten lives to save one man; and Dr. Lisa Benson (Luciana Paluzzi), once Rankin’s girlfriend but now engaged to Elliott.

Rankin leads a team to the asteroid to plant bombs which will blow it to dust – leading to a tense countdown while Elliott tries to insist that everyone wait for one team member who hasn’t come back to the ship even as the bombs are about to explode. Although they do manage to get away without dying, one man has some asteroid slime stuck to his spacesuit and once it’s back on Gamma 1, it quickly absorbs energy and turns into rapidly multiplying one-eyed monsters with electrically charged tentacles. The monsters are endearingly ridiculous, a child’s idea of deadly space trolls, and much of the movie’s charm comes from the straight-faced way the cast fight for their lives against them.

Although written and produced by Americans, with a mostly English-speaking cast, the movie has the weird and distinctive air of non-English-speaking filmmakers trying hard to simulate what they think a Hollywood movie should be. Perhaps best seen in a party atmosphere, it evokes memories of childhood Saturday matinees where quality and sense had little or no part in the viewing experience.

The Warner Archive Blu-ray has a nice, colourful widescreen transfer, but unfortunately no extras.

*

Earthquake (Mark Robson, 1974)

Opinions inevitably change over time, and it’s sometimes difficult to figure out what one might once have been thinking. During the early-’70s disaster movie boom, one of my favourites was Mark Robson’s Earthquake (1974). I liked it better than Ronald Neame’s The Poseidon Adventure (1972) and John Guillermin’s The Towering Inferno (1974). But seeing these movies again today, Earthquake really doesn’t hold up, while the other two still work well on their own terms. The best I can figure is that I preferred Earthquake at the time because of the scale of the disaster with its apocalyptic imagery of a ruined Los Angeles.

All these disaster movies are packed with stereotyped characters dealing with soap opera conflicts while trying to survive the particular catastrophe facing them. Despite the presence of Mario Puzo’s name in the Earthquake credits, the characters are much more cartoonish than those created by Stirling Silliphant for the other two films. Richard Roundtree’s low-rent stunt rider hoping to make it big in Vegas; Marjoe Gortner’s supermarket manager who goes full psycho as a National Guard officer given the power to shoot looters; Charlton Heston as the principled engineer worried that his father-in-law’s architectural firm is building unsafe towers; Ava Gardner as his unhinged alcoholic wife whose jealousy is driving him into the arms of would-be actress Genevieve Bujold, the death of whose husband Heston feels responsible for; George Kennedy’s cop who just wants to get the bad guys but keeps running into rules which hamper him … none of them carry any weight, leaving the movie to rely on its effects. Which also don’t hold up very well; matte shots and miniatures may not be as glaringly fake as those in The Green Slime, but they don’t look particularly convincing either.

The hi-def transfer on Universal’s bare bones Blu-ray only serves to make the effects look shoddier.

*

The Last Starfighter (Nick Castle, 1984)

There are bad effects and there are dated effects. The former can undermine one’s enjoyment of a movie, while the latter can actually enhance it. (Something George Lucas fails to understand; when he digitally “upgrades” the model work and optical effects in the early Star Wars movies, he destroys whatever charm they had and erases the groundbreaking work his technicians accomplished with what was then available.) Being able to see how effects have evolved over the years, for someone like me, serves to illustrate how CGI has paradoxically diminished the craft of special effects. Nick Castle’s The Last Starfighter (1984) provides a case in point.

Made seven-odd years after Star Wars and five years after Alien (1979), as computer imagery was being born, this kid-friendly sci-fi adventure with its digitally created spaceships has the weightless cartoonish feel which still affects a lot of CGI even today. Properly photographed, carefully lit models have a tactile presence which even the best CG has trouble emulating. But what makes The Last Starfighter interesting even now is the way it displays the origins of CG effects in video game technology. In fact, this is built into the movie.

Trailer park kid Alex (Lance Guest) alleviates the boredom of his life by becoming a master at the arcade game outside the park office. Turns out, this is actually a plant by intergalactic conman Centauri (Robert Preston, over-acting in full Harold Hill mode) as part of a wide-ranging search for possible starfighter pilots to help wage space war. Alex gets scooped up and joins a multi-species force as the apocalyptic battle draws nigh; when the rest of the fleet is destroyed, Alex alone must defeat the enemy a la Luke taking down the Deathstar.

There are clear echoes of The Last Starfighter in Ender’s Game, but Jonathan Betuel’s script never goes near any moral questions about using kids to wipe out another species. Alex just accepts that the guys who have recruited him are on the right side of history … the movie is more like one of Robert A. Heinlein’s juvenile space adventures.

The Last Starfighter is very much of its time, a transitional production between classic effects techniques and modern digital effects which were still in their infancy in the mid-1980s. Mildly entertaining, kind of cheesy, but an interesting historical artifact.

The transfer on Universal’s Blu-ray is excellent; the image is sharp, with bright colours and strong contrast. There’s a commentary by director Castle and production designer Ron Cobb, plus a couple of making-of featurettes totaling almost an hour.

*

Patrick (Richard Franklin, 1978)

Patrick (1978) was one of the key films in the heyday of Ozploitation, and the first of two collaborations between writer Everett De Roche and director Richard Franklin (the second being Road Games [1981]). Franklin quickly headed for the States and a career which never quite amounted to much after Psycho II (1983), while De Roche stayed down under and ended up working mostly in television, with a brief flurry of resurgent Ozploitation in the late 2000s (Jamie Blanks’ Storm Warning and the Long Weekend remake).

Patrick belongs to the telekinetic horror sub-genre which has produced such B classics as Ray Danton’s Psychic Killer (1975), Jack Gold’s The Medusa Touch (1978) and of course Brian De Palma’s Carrie (1976). Nurse Kathy Jacquard (Susan Penhaligon) takes a job at the slightly creepy Roget Clinic in Melbourne, where she’s assigned to keep an eye on comatose patient Patrick (Robert Thompson), who killed his parents three years earlier. Patrick is being kept alive for experimental purposes by Dr. Roget (Robert Helpmann), and Kathy is assured that he’s completely brain dead.

But on her night shifts she begins to sense that he’s actually conscious and she tries to communicate with him. Patrick responds by beginning to psychically stalk Kathy, attacking Brian Wright (Bruce Barry), a doctor she’s attracted to while separated from her estranged husband Ed (Rod Mulliner). The more Kathy tries to communicate with him, the more violent Patrick becomes.

It seems like a fairly standard, familiar horror thriller now, but the story is handled efficiently by De Roche and Franklin and the cast is pretty good for a low budget feature. So while there are no major points for originality, Patrick remains an effective little movie.

Severin’s transfer is okay and fairly representative of a film of this vintage and budget. Extras include a commentary from director Franklin (with some contributions from De Roche), a vintage television interview with Franklin, and over an hour of material culled from Mark Hartley’s interviews for his Ozploitation documentary Not Quite Hollywood (2008).

*

The Late Great Planet Earth (Robert Amram, 1979)

I picked up a copy of this oddity on Blu-ray for a few bucks at a local store for two reasons. The first, its amusement value as one of those cheap pseudo-documentaries which were quite prevalent in the 1960s and ’70s, covering subjects like UFOs and Bigfoot. (Alas, it lacks the energy and visual style of Harald Reinl’s Chariots of the Gods [1970], which benefited greatly from Peter Thomas’ catchy score.) The second reason is the presence of Orson Welles as on-screen personality and narrator. I love Welles’ work as a filmmaker, but his enduring need for money to support his filmmaking led him to take pretty much any acting job that came along. (He jumped from Harry Kümel’s surreal masterpiece Malpertuis in 1971 to Bert I. Gordon’s cheap horror movie Necromancy in 1972, while he was struggling to make his sadly unfinished Don Quixote.)

Based on the inexplicably best-selling 1970 book by evangelist Hal Lindsey, written to explain the domestic and international turmoil of the ’60s as the fulfillment of End Times prophecies in the Bible, the movie is a largely random collection of stock footage of wars, riots and natural disasters slathered with portentous music and even more portentous narration spoken with such dignified solemnity by Welles that it becomes quite comic. Apparently the original cut ran short for a feature and Rolf Forsberg was hired to write and direct a number of reenactments from the Bible – including an interminable opening sequence in which a mob pursues a prophet through the desert and up a mountain; at the top, he’s stoned and falls to his death. Through the magic of movie time travel, his body becomes a dusty skeleton which is come across by Welles, also apparently wandering in the wilderness, who delivers the film’s thesis to the camera.

The Late Great Planet Earth is a clumsy movie, its cliched Christian fundamentalism no longer amusing in light of the havoc being wreaked by the religious Right in recent years, but Welles somehow manages to maintain his dignity even as he spouts nonsense he couldn’t possibly have subscribed to himself.

Scorpion Releasing’s Blu-ray doesn’t look too bad considering the movie was cobbled together from multiple sources. There’s a fourteen-minute featurette in which a number of those involved reminisce about the experience of making it … seemingly quite proud of their work.

*

Southern Comfort (Walter Hill, 1981)

Walter Hill had a great streak of original and even innovative movies at the start of his career, but then in 1982 he hit the commercial big-time with 48 Hrs. and somehow never quite regained his momentum, though he directed a steady stream of very uneven features throughout the next two decades. That early streak, beginning with Hard Times (1975) and continuing through The Driver (1978), The Warriors (1979) and The Long Riders (1980), culminated in what remains his finest film, Southern Comfort (1981). Although Hill and co-writers Michael Kane and David Giler strenuously deny that it was their intention, this tense, violent movie is one of the best – if not the best – cinematic treatments of the American experience in Vietnam, an allegory of national arrogance and ignorance set on the homefront.

A squad of Louisiana National Guardsmen on weekend manoeuvres get lost in the swamp and run afoul of barely seen Cajun hunters. Played by an excellent cast, the squad in classic Hollywood style represent a cross-section of society, a bunch of guys who don’t take what they’re doing seriously and end up paying a severe price. With no knowledge or understanding of the landscape they’re traversing and no interest in or respect for the people who live in that landscape, they trash the environment, steal boats, and most foolishly “play war” by shooting blanks at men barely seen on shore.

When these men shoot back with live rounds, the squad begins to fall apart. The officer (Peter Coyote) dies quickly and others vie for dominance – Reece (Fred Ward), who against regulations has brought his own live ammo; Bowden (Alan Autry), an uptight religious fundamentalist; Spencer (Keith Carradine), a laid back guy who just wants to get by; and Hardin (Powers Boothe), a man who has a problem with authority. Spencer and Hardin bond to a degree because both are smart enough to know that their own lives have been put in danger by the stupidity of their fellow Guardsmen.

As in Vietnam, these men have been sent somewhere for no good reason, without the knowledge or skills to understand and function in a hostile environment; leaderless, they have no objective other than to survive, while there’s no way of knowing whether anyone they meet is “friend” or “enemy” – and those who are enemies are only in that role because of the squad’s intrusion into their home ground. The Guardsmen face danger and death simply because they’ve been sent somewhere they have no business being.

The cast is uniformly excellent; Hill’s staging of the constantly shifting group dynamics is flawless; Andrew Laszlo’s cinematography captures the wet misery of their passage through the swamp, while also evoking the natural beauty of the landscape; and Ry Cooder provides an understated score which evokes the time and place – climaxing in the extended stalking sequence through a Cajun village as the locals celebrate and dance while the two surviving Guardsmen fight for their lives in backrooms and alleys to an accompaniment of lively fiddle music. Hill’s lean style seems completely undated and its depiction of American arrogance and ignorance about the world is still pertinent.

The image on Shout! Factory’s Blu-ray looks terrific, supporting the muted colour scheme of Laszlo’s photography with a richly detailed, film-like texture. The only extra is a half-hour interview-based retrospective … during which we learn just how grueling the shoot in the swamp was, and hear a number of times that this is not a Vietnam allegory, an assertion negated by everything we see during the movie.

Comments